Overview

The Queensland Audit Office (QAO) makes recommendations and provides insights to state and local government entities to help them improve their delivery of public services. This, in turn, helps make a difference to the lives of Queenslanders.

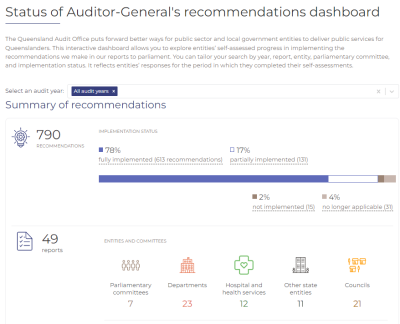

This is our third report to parliament on the status of Auditor-General’s recommendations. We asked 98 entities to report on their implementation of 678 recommendations from 41 QAO reports we tabled in parliament. We found 20 entities of 98 entities reported fully implementing our recommendations. Fourteen of the 18 reports we tabled in parliament in 2020–21 and 2021–22 have outstanding recommendations.

Based on entities' self-assessments, we share insights on their progress and highlight common or key opportunities for improvement. The most common type of recommendations entities failed to implement relate to regulatory and oversight practices, with some remaining unclear of their responsibilities in this area.

Tabled 28 November 2023.

Auditor-General’s foreword

It has been my privilege to lead the Queensland Audit Office (QAO) over the past 6 years. As parliament’s independent auditor, QAO is uniquely positioned to examine the performance of state and local government entities and share insights from our work across the public sector. These insights can help entities take advantage of improvement opportunities and learn from the better practices of others.

This is the third and my last report that I will table on the status of my recommendations before my tenure ends in July 2024. I first introduced this report to help parliament and entities track the status of the recommendations made in my reports. They are also an important avenue for sharing the wider learnings we glean from across our work with all entities.

While I always ask entities if they agree with my recommendations, I cannot force them to act. Entities themselves need to want and drive the change and recognise the value of my recommendations and the improvement opportunity they present. While this report identifies that entities are actioning my recommendations, some long outstanding recommendations remain. Opportunities also exist for entities to enhance their actions in implementation by comparing their approach and status to their peers.

In this report, I summarise the progress entities are making in implementing my recommendations from 2020–21 and 2021–22, and outstanding recommendations (partially implemented and not implemented) from last year’s report. I also share the trends and challenges across the public sector we see emerging.

As I reflect on the reports I have tabled between 2020–21 and 2021–22, some prominent themes emerge:

- good regulatory practices need to be risk-based and intelligence-led

- measuring and reporting performance is essential to making informed decisions

- effective audit committees are a cornerstone of good governance.

I have conducted several audits between 2020–21 and 2021–22 examining the performance of regulators and entities with oversight functions. These entities play a critical role for Queenslanders. They help keep our communities safe and they help protect our environment. Despite their important role, I have repeatedly found they need to better understand their regulatory responsibilities and strengthen their regulatory practices. This includes using data and intelligence to inform their regulatory approach and ensuring their enforcement activities target more severe risks.

Effectively measuring performance enables public sector entities to make informed decisions and remain agile. Since my appointment, the most common type of recommendation that I have made involves entities improving their performance monitoring and reporting practices. It also represents one of the most common types that entities fail to implement. The reasons why entities fail to implement these recommendations vary. But some typical challenges include the absence of a performance and learning culture, unclear goals and objectives, an inability to access quality data, and a lack of momentum by state departments due to periodic major disruption through machinery of government changes and leadership changes.

Recommendations to strengthen governance arrangements were also a focus in my 2020–21 and 2021–22 reports. Many of these recommendations targeted strengthening the role of audit committees. I have stressed the importance of effective audit committees. While departments have reported actions they have taken to improve their audit committees, further opportunities exist. This includes ensuring all members are independent of management and not an employee of the entity or another government entity.

Each year, we will follow up on the progress entities are making implementing audit recommendations. We will use the responses we receive from entities’ self-assessments to help inform which audits we select for a more detailed follow-up audit and report to parliament.

Through our follow-up audits, and new audits on related topics, we continue to find that some entities have overstated their progress in implementing our recommendations. For example, the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries previously reported fully implementing the 5 recommendations from our report Biosecurity Queensland's management of agricultural pests and diseases (Report 12: 2016–17). However, when we followed up on these recommendations as part of our audit on Managing invasive species (Report 1: 2023–24) we reported that 3 of the 5 recommendations were only partially implemented. It is important that entities ensure the actions they take address the underlying issues that we identify. It is also important that entities and audit committees do not close recommendations until the committee receives assurance from internal audit that the actions taken are imbedded and operating effectively.

I hope this report gives parliamentarians, parliamentary committees, and members of the public a more complete picture of the progress entities are making in implementing my recommendations towards better public services for Queenslanders.

Brendan Worrall

Auditor-General

Report on a page

The Queensland Audit Office makes recommendations to state and local government entities to support better delivery of public services.

Our analysis of entities’ reported progress against the different types of recommendations we make highlights common challenges and opportunities for the public sector. In this report, we offer insights about how entities can improve their systems and practices.

Our recommendations focus on many different aspects of public service delivery. We ensure our recommendations are client focused, address the root cause, and add value to the public sector.

What did we examine?

Note: These 41 reports to parliament included 205 unique recommendations. However, we made some of these recommendations to multiple entities, which we count as individual recommendations. So, overall we made 678 individual recommendations.

What did we find?

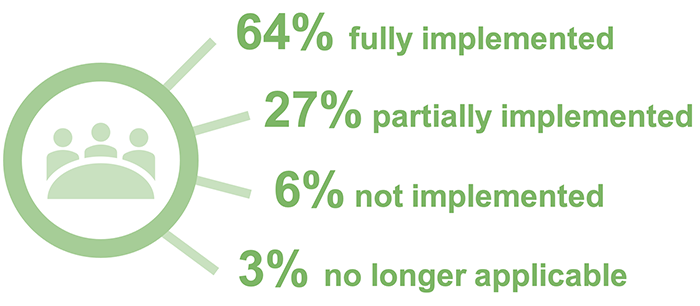

Entities reported the following progress with implementing our recommendations:

|

Appendix B summarises entities’ self-assessed progress in implementing our recommendations. The best way to explore their reported progress on each recommendation is via our interactive dashboard available at www.qao.qld.gov.au.

Insights from entities’ responses

- Entities need to strengthen their regulatory and oversight practices. We made 88 recommendations on regulation and oversight in 2020–21 and 2021–22. These were the most common type of recommendations that entities failed to implement. We found some did not have a good understanding of their regulatory and oversight responsibilities.

- Audit committees play a critical role in the governance of an entity. State government entities reported good progress implementing recommendations from our report on the Effectiveness of audit committees in state government entities (Report 2: 2020–21). While departments have largely actioned the recommendations in this report, opportunities still exist for some departments to enhance the actions they have taken to align with better practice.

Queensland Treasury is updating its Audit Committee Guidelines: Improving Accountability and Performance, which will help audit committees strengthen their independence and oversight.

1. Insights – recommendations and responses

We design our recommendations to help our clients improve their service delivery and learn from the better practices of others. We consult with entities when drafting our recommendations and we ask them to confirm whether they agree with our recommendations. Although we cannot make entities implement our recommendations, we track, report, and share insights on their progress.

For this report, we asked 98 public sector entities, including local governments, to self-assess their progress in implementing the performance audit recommendations we issued from:

- 18 reports tabled in 2020–21 and 2021–22

- 23 reports from earlier years that had outstanding recommendations (we define ‘outstanding recommendations’ as those either not implemented or partially implemented from last year’s report).

Entities reported their progress to us between June and August 2023. This report reflects the status of entities’ self-assessed progress in implementing our recommendations at that time. We have not audited the actions they have taken, and therefore cannot provide assurance over their responses.

We asked entities to assess whether they had fully, partially, or not implemented our recommendations, or whether they assessed the recommendations as no longer applicable (using the criteria detailed in Appendix D). Where entities report fully implementing our recommendations, we expect their actions to address the issue that we identified and to be operating effectively, not to be a plan to address the issue.

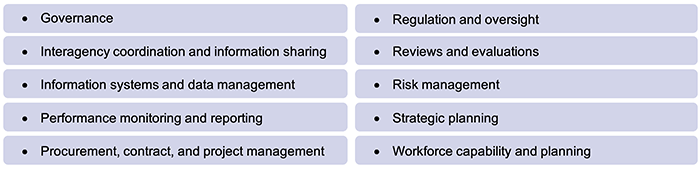

Insights into our most frequent recommendations

We analysed all the recommendations we made in 2020–21 and 2021–22 to identify those we made most often. This gives us some indication of what entities find most challenging.

We grouped our recommendations into 10 categories, as shown in Figure 1A.

Note: We acknowledge that some of the categories above, like risk management, form part of governance. We have separated these to allow for richer analysis.

Queensland Audit Office.

For this year’s report, we added a new category ‘regulation and oversight’ and removed a category ‘complying with and reviewing legislation’, based on the types of recommendations that we made between 2020–21 and 2021–22. We made regulation and oversight recommendations to both:

- regulators (entities responsible for enforcing minimum standards for a particular industry or business activity)

- oversight bodies (entities responsible for performing oversight functions, including maintaining regular surveillance over a system or process and monitoring performance).

Our interactive dashboard captures all recommendation categories from prior years, and is available at www.qao.qld.gov.au/status-auditor-generals-recommendations-dashboard.

Appendix C explains these categories and shows entities’ reported progress against them.

Figure 1B shows the 3 most common categories of recommendations we made in 2020–21 and 2021–22 and the underlying issues our recommendations sought to address.

| Number of recommendations by category | Underlying issues |

|

187 governance recommendations |

|

|

88 regulation and oversight recommendations |

|

|

78 performance monitoring and reporting recommendations |

|

Queensland Audit Office using data self-reported by entities.

Insights into outstanding recommendations

We also analysed entities’ progress against the 10 categories to identify which had the highest number of outstanding recommendations. While governance recommendations were the most common, entities reported making good progress in implementing them. They reported fully implementing 87 per cent (163) of the 187 governance recommendations.

The most common type of outstanding recommendations related to regulation and oversight, followed by performance monitoring and reporting; and procurement, contract, and project management.

Figure 1C shows the status of the 3 most common categories of outstanding recommendations in 2020–21 and 2021–22.

| Recommendation category | Number of outstanding recommendations | Percentage of all outstanding recommendations |

|

Regulation and oversight |

35 |

25% |

|

Performance monitoring and reporting |

21 |

15% |

|

Procurement, contract, and project management |

20 |

14% |

|

Total |

76 |

54% |

Note: There were 140 outstanding recommendations in 2020–21 and 2021–22.

Queensland Audit Office using data self-reported by entities.

Regulation and oversight

| Regulation and oversight are core functions of government. Good regulatory practices are risk‑based and intelligence-led. That is, regulators should use data and intelligence to inform their regulatory approach and ensure their enforcement activities target more severe risks. In 2020–21 and 2021–22, we made 88 regulation and oversight recommendations from 3 reports to parliament. |

We recommended entities strengthen their regulatory and oversight practices by:

- developing and implementing a regulatory framework

- applying targeted risk-based inspections and compliance-monitoring activities

- acting in a timely and effective manner to address non-compliance.

Entities reported implementing 55 per cent (48) of these recommendations, with 40 per cent (35) still outstanding. The remaining 6 per cent (5) were assessed by the entities as no longer applicable.

Most of the outstanding regulation and oversight recommendations were from our report on Regulating animal welfare services (Report 6: 2021–22). We explore why entities failed to implement these recommendations later in this chapter.

Performance monitoring and reporting

| Entities that monitor and report their performance effectively can easily see what they are doing well and what they can improve. They can assess whether the services they deliver are efficient, effective, economical, and providing value for money. |

In 2020–21 and 2021–22, we made 78 performance monitoring and reporting recommendations from 7 reports to parliament. We recommended that entities enhance their performance monitoring and reporting, including:

- developing appropriate performance indicators

- measuring outputs and outcomes

- improving publicly reported performance information.

Entities reported implementing 73 per cent (57) of the 78 recommendations, with 27 per cent (21) still outstanding. More than half of the outstanding performance monitoring and reporting recommendations were from our report on Measuring emergency department patient wait time (Report 2: 2021–22). Hospital and health services reported partially implementing these recommendations and noted the additional work needed to improve their performance-monitoring practices.

Procurement, contract, and project management

| Strong procurement, contract, and project management practices are critical to the success of any organisation. We made 59 procurement, contract, and project management recommendations from 4 reports to parliament tabled in 2020–21 and 2021–22. |

We identified opportunities where entities could strengthen their procurement, contract, and project management practices by:

- reviewing existing projects to ensure they remain viable and the highest priority

- ensuring current projects are set up with the right mix of skills and resources, and roles and responsibilities are clearly defined

- proactively managing contractor performance.

Entities reported implementing 54 per cent (32) of the 59 recommendations, with 34 per cent (20) of the recommendations still outstanding. They assessed the remaining 12 per cent (7) as no longer applicable.

Most of the outstanding procurement, contract, and project management recommendations were from our report on Contract management for new infrastructure (Report 16: 2021–22). Entities need to implement these recommendations quickly and effectively, particularly given the government’s significant infrastructure investment over the next 4 years. Investment in infrastructure remains a key focus for our office and we have several upcoming audits in our Forward work plan 2023–26, available on our website at: www.qao.qld.gov.au/audit-program.

Insights from entities’ responses

The important role of regulators and oversight entities

Regulators and oversight entities are responsible for ensuring appropriate standards are met. Their role is critical to maintaining community safety and protecting the environment and the rights of Queenslanders. For example, the Queensland Police Service is responsible for ensuring firearm holders comply with their licence conditions and for seizing firearms from people who are no longer safe to have one. Local governments (councils) are responsible for inspecting food businesses to ensure they comply with food safety standards and that the food they serve is safe for public consumption.

Despite regulation being a core function of state and local governments, we have repeatedly found that good regulatory performance in enforcing minimum prescribed standards is often absent.

We undertook 3 audits between 2020–21 and 2021–22, which examined how effectively entities perform and oversee their regulatory functions. They included:

- Regulating dam safety (Report 9: 2021–22)

- Regulating animal welfare services (Report 6: 2021–22)

- Regulating firearms (Report 8: 2020–21).

Across these 3 audits we found regulators and oversight entities needed to better understand their role and responsibilities and take a more proactive enforcement approach. This has been a consistent theme across other regulatory-focused audits we have undertaken, including Managing coal seam gas activities (Report 12: 2019–20), Managing consumer food safety in Queensland (Report 17: 2018–19), and Managing transfers in pharmacy ownership (Report 4: 2018–19).

Self-assessing your performance against good regulatory practices

As mentioned above, our audits on regulatory practices continue to result in similar issues being reported. While recommendations in our reports may be made to individual entities, the learnings from our reports should be considered across government. Our reports provide entities with the opportunity to review and improve their own practices, even when they are not part of the audit.

To address this issue, our report Regulating animal welfare services included a section focusing on the insights and wider learnings we have for all regulators. We recommended that all public sector regulators and oversight bodies self-assess against better practices identified in Appendix C of the report (recommendation 5). This recommendation also included implementing changes to enhance regulatory performance, where necessary.

Our regulatory better practice guide is a principles-based model. It provides a summary of good regulatory practices based on 4 key principles: plan, act, report, and learn. We developed insights by drawing on the findings of this audit, our previous audits on regulatory practice, and other better practice guides.

We recognised the learnings, and the improvement opportunities, identified in these good regulatory practices were relevant to all entities with regulatory and oversight responsibilities. Accordingly, we recommended all public sector regulators and oversight bodies assess all parts of their regulatory and oversight functions (not just those responsible for regulating animal welfare services).

In December 2021, we wrote to relevant entity chief executive officers informing them of the recommendation and advising that we would follow up on their progress in 2023. We also held an insights session for regulators in May 2022 to discuss the findings from our audits and the better practice principles for regulators. We invited all entities that we wrote to advising that we would follow up on this recommendation as part of this report. Despite this, some large entities with multiple and significant regulatory roles did not attend this session. Several of these entities are yet to fully implement this recommendation.

Entities reported limited progress self-assessing performance against the better practices identified in Appendix C of the report. Only 47 per cent (33) of the 70 entities that we asked reported fully implementing it. Some entities reported that they lacked the resources to do it. It is unlikely that this recommendation would have been resource intensive or costly to action.

We found, when discussing with entities their progress, some did not understand their regulatory and oversight responsibilities under the legislation. Others took a narrow view of their regulatory role and did not understand the full breadth of their responsibilities. Given this is a core function of government, entities must understand their role to ensure their operations align with their legislative responsibilities.

Measuring the outcomes of your actions

Some regulators, like the Queensland Police Service (QPS), have made good progress implementing our recommendations to strengthen their regulatory practices. QPS also measured the outcomes of its action and explained these clearly in its response.

QPS reported fully implementing 10 of the 13 recommendations that we made in Regulating firearms. This included implementing our recommendation for developing a clear policy on the role firearm regulation plays in balancing community safety with the rights of licence holders. In response, QPS reviewed its weapons licensing policy and provided clear guidance and training to its officers assessing licence applications. By implementing our recommendations, QPS reported that the number of new licence applications it rejected increased by 39 per cent from 2020 to 2021. It also reported that the number of licences that it suspended increased by 16.5 per cent over this period. QPS’s enhanced regulation is likely resulting in better public safety outcomes for the community.

All entities need to measure the success of their programs and activities to determine what is working well and what they can improve.

The value of audit committees

Audit committees play a critical role in the governance of an entity. Effective audit committees hold management to account by monitoring the effectiveness of their performance and overseeing the implementation of audit recommendations. As we have noted in prior years, some entities remain uncertain about their progress in implementing our recommendations because they do not have effective systems to track them. Subsequently this can make it difficult for audit committees to effectively hold management to account.

In our report Effectiveness of audit committees in state government entities (Report 2: 2020–21) we directed 6 of our 11 recommendations to audit committees, audit committee chairs, and chief executive officers. This included recommending audit committees:

- clearly define their role, ensuring it is appropriate and specific to the entity

- remain informed of the entity’s core functions and systems, and the key risks and issues it faces

- review their performance annually against their annual workplan.

Departments reported good progress implementing these recommendations. Seventeen of the 21 departments reported fully implementing these recommendations. Only 4 departments reported recommendations outstanding. However, it was clear from reviewing the responses provided that the actions taken to implement our recommendations varied across departments. The response from some departments also indicates that they did not fully understand some of our recommendations. Departments may wish to reassess their actions against those of their peers to identify whether further action could be taken to implement these recommendations, even where they have assessed the recommendations as being fully implemented.

We addressed the remaining 5 recommendations to Queensland Treasury. This included recommending that it updates the Audit Committee Guidelines: Improving Accountability and Performance to:

- mandate that all members of audit committees for state government entities be independent of management and not an employee of the entity or another Queensland state government entity

- provide clearer guidance about how audit committees can source suitable candidates and effectively assess and improve their performance practices.

In our report Effectiveness of the State Penalties Enforcement Registry ICT reform (Report 10: 2019–20) we also recommended that Queensland Treasury update its audit committee guidelines to ensure audit committees are required to monitor and receive reports from management on risks for major information and communication technology (ICT) projects.

Queensland Treasury initially agreed to update its guidelines by June 2022. In April 2022, the Under Treasurer requested, and we agreed to, an extension for issuing the updated guidelines to 31 December 2022. In June 2023, Queensland Treasury reported that it has only partially implemented these recommendations.

It is important that Queensland Treasury acts quickly to implement these recommendations. Issuing the updated guidelines may assist departments in reassessing whether they have fully implemented our recommendations and have adopted better practice. The updated guidance will also help audit committees strengthen their independence and oversight and improve their performance.

Queensland Treasury is currently updating its guidelines and has been liaising with us on proposed amendments. Once finalised, the revised guidelines will be published on Queensland Treasury’s website. While it is important that Queensland Treasury updates its guidelines, there is nothing stopping entities from acting on these recommendations themselves and ensuring their committees are operating effectively. This includes ensuring that audit committee members are independent of the entity’s management and are not employees of the entity or another Queensland state government entity.

Fully independent audit committees provide greater objectivity and create a better foundation for robust and incisive discussions and questions. They have increased ability to critically assess recommendations made to the entity by QAO, internal audit, and other assurance providers and hold management to account for the actions it takes in addressing the recommendations.

While most of the 21 departments included in the report now have audit committees with a majority of independent members, only 2 departments have fully independent audit committees.

In 2023–24, we plan to examine the effectiveness of local government audit committees.

2. Status of implementation

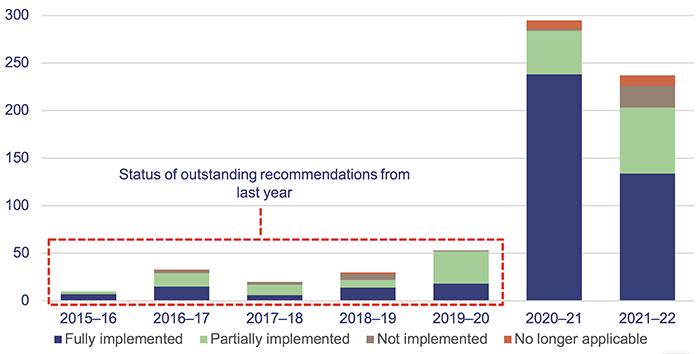

We make recommendations to help entities improve the public services they deliver. Our recommendations may address performance gaps, inefficiencies, and unnecessary risk across the public sector. We may also identify better practices, which other entities could consider. In this section, we discuss the progress that entities reported in implementing our recommendations. This includes:

- 532 recommendations from 18 reports tabled in 2020–21 and 2021–22

- 146 recommendations from 23 reports tabled between 2015–16 and 2019–20, which entities reported as outstanding (partially implemented and not implemented) in last year’s report.

We begin with the overall status of implementation, then break it down into years and provide detailed analysis for specific reports. We selected these reports based on their number of outstanding recommendations or the important themes. We then report on the implementation of recommendations by departments, hospital and health services, local governments, and other entities.

Overall status of implementation

We asked 98 entities to self-assess their progress in implementing 678 performance audit recommendations from 41 reports between 2015–16 and 2021–22. Appendix B includes a list of the reports we asked entities to self-assess against, and a summary of entities’ self-assessed progress.

Entities reported that they had:

- fully implemented 64 per cent (432)

- partially implemented 27 per cent (185)

- not implemented 6 per cent (38).

They also reported that 3 per cent (23) of recommendations were no longer applicable to them.

Figure 2A shows the status of all recommendations we issued in 2020–21 and 2021–22 and the status of recommendations that entities reported were outstanding last year.

Queensland Audit Office using data self-reported by entities.

Status of recommendations from 2021–22

Entities reported fully implementing all recommendations from 2 reports tabled in parliament in 2021–22 or assessed the remaining recommendations as no longer applicable. These included:

- Improving access to specialist outpatient services (Report 8: 2021–22)

- Regulating dam safety (Report 9: 2021–22).

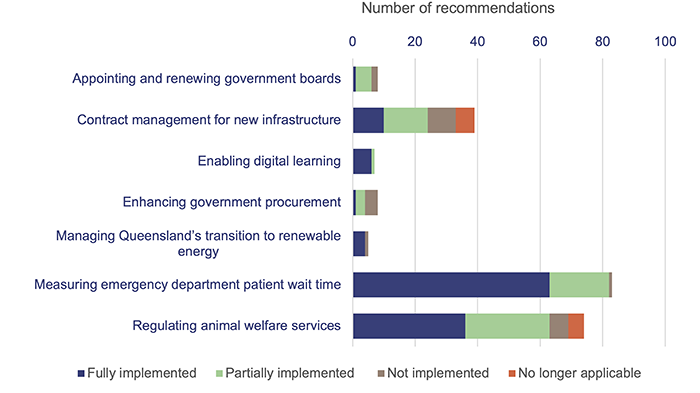

2021–22 reports to parliament with outstanding recommendations

Entities reported that the remaining 7 reports to parliament from 2021–22 have outstanding recommendations. We show these in Figure 2B.

Queensland Audit Office using data self-reported by entities.

In the following section, we break down the progress that entities reported implementing recommendations from our report on Contract management for new infrastructure (Report 16: 2021–22). We selected this report based on the number of outstanding recommendations and the inherent risks associated with infrastructure contracts.

Managing infrastructure contracts effectively

Effective contract management practices outline responsibilities, set expectations, and establish time frames. They ensure infrastructure projects meet their objectives and help minimise the risk of delays and cost overruns. The importance of good contract management practices cannot be overstated, particularly given the significant investment in infrastructure in the coming years. The Queensland Government has committed $89 billion over the next 4 years to:

- transform the state’s energy system

- enhance infrastructure across regional Queensland

- improve the state’s transport network

- prepare for the Brisbane 2032 Olympic and Paralympic Games.

In Contract management for new infrastructure, we examined how effectively government entities manage contracts for the delivery of new infrastructure. We made 11 recommendations. We addressed:

- all 11 recommendations to the Department of Energy and Public Works (DEPW)

- 9 recommendations to the Department of Education (DOE)

- 1 recommendation to the other 19 departments (39 recommendations in total).

We focused on DEPW and DOE because between them, they deliver approximately 60 per cent of the state’s building infrastructure projects. As the lead agency, DEPW is responsible for the government’s infrastructure contract framework. We recommended it:

- strengthen its whole-of-government framework to clearly state minimum requirements for managing infrastructure contracts and provide guidance to public sector entities

- review and update its whole-of-government framework every 3 years to reflect better practices.

DEPW reported that all recommendations remain outstanding. It reported that it had consulted agencies about its framework but was yet to publish the revised guidelines. As the lead agency, DEPW has a critical role promoting awareness about better contract management practices across the public sector.

We also asked government departments to review their internal contract management policies, procedures, and guidance to ensure they reflect better practice. We note that some departments reported only partially implementing this recommendation.

Government departments need to ensure their practices reflect better practice and they are managing contracts effectively. This is even more important given the key infrastructure projects that will need to be delivered for the Brisbane 2032 Olympic and Paralympic Games.

Recommendations assessed as no longer applicable

Entities reported that 11 recommendations in 2021–22 were no longer applicable. Six departments reported that recommendation 11 from Contract management for new infrastructure was no longer applicable because they were not responsible for infrastructure contracts, or they engage another entity to manage their contracts.

Five entities reported that recommendation 5 from Regulating animal welfare services was no longer applicable because they do not have a regulatory role.

We agree that these recommendations are no longer applicable.

Status of recommendations from 2020–21

Entities reported fully implementing all recommendations from 2 reports tabled in parliament in 2020–21 or assessed the remaining recommendations as no longer applicable. These included:

- Queensland Health’s new finance and supply chain management system (Report 4: 2020–21)

- Responding to complaints from people with impaired capacity—Part 2: The Office of the Public Guardian (Report 14: 2020–21).

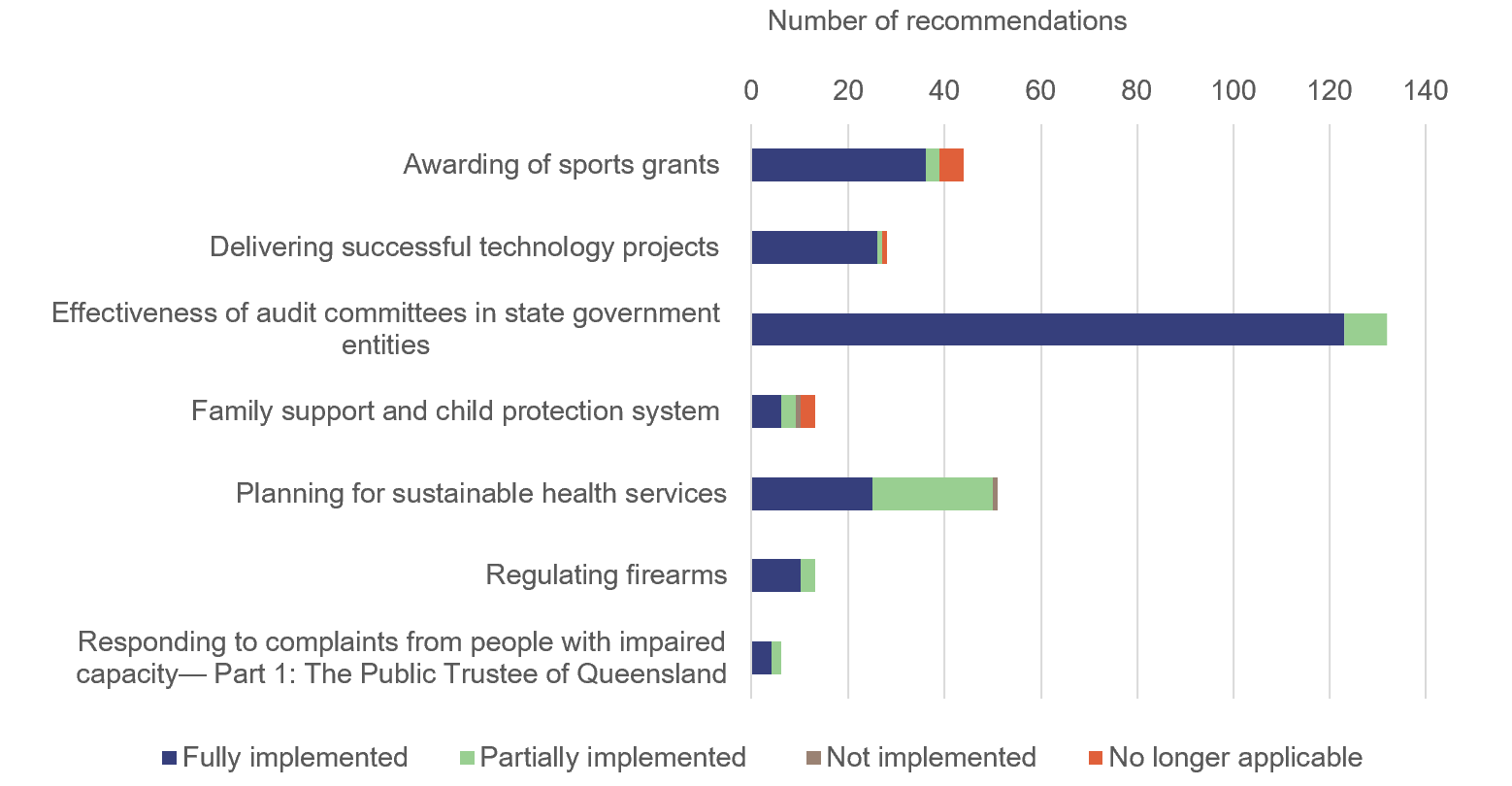

2020–21 reports to parliament with outstanding recommendations

Entities reported that the remaining 7 reports to parliament from 2020–21 have outstanding recommendations. We show these in Figure 2C.

Queensland Audit Office using data self-reported by entities.

In the following section, we break down the progress that entities reported implementing recommendations from our report on Planning for sustainable health services (Report 16: 2020–21). We selected this report based on the number of outstanding recommendations and the importance of Queensland’s health system delivering sustainable healthcare.

Importance of sustainable healthcare

Demands on Queensland’s health system are increasing. A growing and ageing population, rising costs, and staff shortages are adding pressure to a system already under strain. Effective planning is needed to ensure Queensland’s health system can meet the needs of current communities, without compromising the health of future generations. In the 2023–24 Budget, the Queensland Government committed $25 billion over 4 years to improve Queensland’s health system.

In our report Planning for sustainable health services, we examined how the Department of Health and the 16 hospital and health services (HHSs) work together to plan for sustainable health services. We made 7 recommendations to the Department of Health and the HHSs (52 recommendations in total). Gold Coast HHS did not accept recommendation 5 from this report.

We made 4 recommendations to the Department of Health, including:

- implementing a comprehensive integrated planning framework that enables strategic and operational plans

- developing a rolling medium-term implementation roadmap showing how My Health, Queensland’s future: Advancing Health 2026 will be achieved, including clearly explaining priorities for a sustainable health system

- implementing and evaluating statewide workforce plans for critical employee groups and working with HHSs to strengthen capability and capacity of staff who support planning.

We addressed the remaining 3 recommendations to the 16 HHSs: These included:

- developing a set of priorities aligning with the statewide priorities

- developing appropriate performance indicators for health service and enabling plans, and regularly evaluating the success of long-term plans.

Although the department and HHSs have begun implementing these recommendations, progress has been slow.

The department reported partially implementing all 4 recommendations that we made. It has begun to draft an integrated planning framework and a workforce strategy. It has also articulated system priorities under a new 10-year vision for the health system.

The HHSs reported fully implementing 53 per cent (25) and partially implementing 45 per cent (21) of the 47 recommendations. Central Queensland HHS reported not implementing one recommendation.

Some HHSs reported that they intended aligning their priorities and plans with the state’s but were waiting on the department to finalise its framework, strategies, and action plans. It is important that the department acts quickly to implement these recommendations to provide clarity on strategic priorities and enable more enhanced integrated planning.

Recommendations assessed as no longer applicable

Entities reported that 9 recommendations from 3 reports to parliament in 2020–21 were no longer applicable.

The Department of Energy and Public Works and Queensland Corrective Services reported that 2 recommendations from Awarding of sports grants (Report 6: 2020–21) were no longer applicable. The Public Sector Commission also reported that one recommendation from this report was no longer applicable. They reported these recommendations were no longer applicable because they are not responsible for awarding grants.

The Department of Housing reported that recommendation 3 from Delivering successful technology projects (Report 7: 2020–21) was no longer applicable because it was not currently implementing any technology projects. It noted that it would apply the requirements of the recommendation for future projects.

The Department of Child Safety, Seniors, and Disability Services (DCSSDS) and the Department of the Premier and Cabinet reported that recommendation 8 from Family support and child protection system (Report 1: 2020–21) was no longer applicable because the interdepartmental committee (which the recommendation referred to) was discontinued, having fulfilled its original purpose.

We agree that these 8 recommendations are no longer applicable.

The Queensland Police Service (QPS) reported that recommendation 4 from Family support and child protection system (Report 1: 2020–21) was no longer applicable. We recommended that the Department of Child Safety, Youth and Women and entities with mandatory reporting responsibilities establish a multi‑disciplinary intake process for efficiently and effectively triaging all child harm reports. QPS reported that DCSSDS had reviewed its intake process and made several enhancements. It also noted other efforts underway to improve the sharing of information. However, DCSSDS and the Department of Health, which also has mandatory reporting responsibilities, reported partially implementing this recommendation and that additional work was needed. Therefore, we do not agree that this recommendation is no longer applicable.

Status of outstanding recommendations from prior years

In our report 2022 status of Auditor-General’s recommendations (Report 4: 2022–23), we highlighted that 146 recommendations were outstanding. Of these, entities reported this year:

- fully implementing 41 per cent (60)

- partially implementing 48 per cent (70)

- not implementing 9 per cent (13).

They reported that the remaining 2 per cent (3) of recommendations were no longer applicable.

We also identified that the status of some recommendations included in last year’s report were revised downward this year. This included where responsibility for the recommendation was transferred to a different department following machinery of government changes and the new department reassessed the status of the recommendation.

An example of this was the reassessment of the outstanding recommendations from our report Delivering shared corporate services in Queensland (Report 3: 2018–19). In last year's report, the former Department of Communities, Housing and Digital Economy assessed the 5 outstanding recommendations as partially implemented. This year these recommendations were all assessed as not implemented, following the transfer of responsibility for Queensland Shared Services to the Department of Transport and Main Roads in May 2023.

Age of outstanding recommendations

We assessed the age of recommendations outstanding from reports tabled in 2015–16 to 2020–21. We excluded from our analysis outstanding recommendations from reports tabled in 2021–22, given entities had less than a year to implement them.

Figure 2D shows the age of the 131 outstanding recommendations.

Queensland Audit Office using data self-reported by entities.

Three recommendations made to HHSs remain partially implemented from our report Queensland public hospital operating theatre efficiency (Report 15: 2015–16), despite being issued more than 7 years ago.

Similarly, 17 recommendations remain outstanding despite being issued over 6 years ago. These include:

- 12 recommendations (11 partially implemented, one not implemented) from our report Forecasting long‑term sustainability of local government (Report 2: 2016–17)

- 5 recommendations (3 partially implemented, 2 not implemented) from our report Efficient and effective use of high value medical equipment (Report 10: 2016–17).

Recommendations assessed as no longer applicable

Entities reported that 3 recommendations from 3 reports to parliament in 2016–17 and 2018–19 were no longer applicable.

Gold Coast HHS reported that one recommendation from Efficient and effective use of high value medical equipment was no longer applicable. It took an alternative action to address the recommendation.

Metro South HHS reported that one recommendation from Digitising public hospitals (Report 10: 2018–19) was no longer applicable. It reported that it had captured data on the benefits of e-Health’s Integrated e-Medical Record program in response to the recommendation. However, it noted that the Department of Health had decommissioned the group collecting and reporting on statewide data and no further data was being collected.

Similarly, the Queensland Police Service reported that one recommendation from Delivering forensic services (Report 21: 2018–19) was no longer applicable. It reported that the 2022 Commission of Inquiry into Forensic DNA testing recommended setting up a new independent statutory body responsible for managing forensic services.

We agree that these recommendations are no longer applicable.

Progress of implementation by entity type

In the following section, we analyse reported progress in implementing recommendations by:

- departments

- hospital and health services

- local governments

- other entities.

Note: Figures show the status of recommendations made in 2020–21 and 2021–22 and outstanding recommendations from prior years.

Queensland Audit Office.

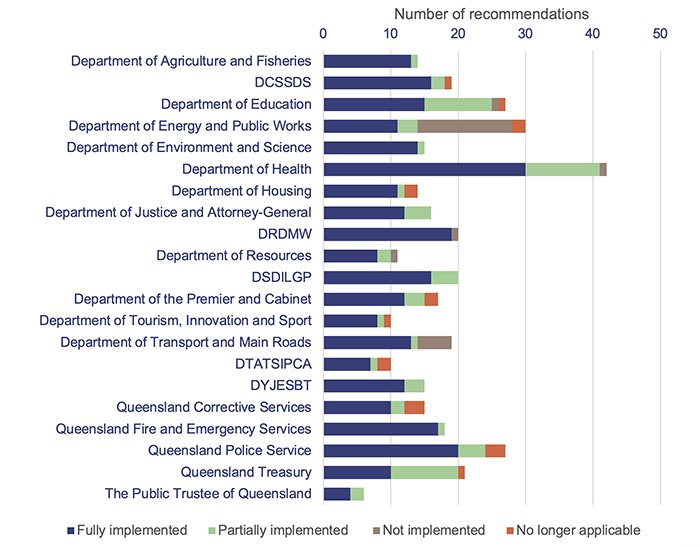

Departments

We asked 22 departments to self-assess their progress in implementing 348 recommendations issued to them in 2020–21 and 2021–22 and 48 outstanding recommendations from last year’s report. They reported implementing 72 per cent of the 396 recommendations. The Public Sector Commission is the only department that reported fully implementing all recommendations. In contrast, 10 departments reported fully implementing all recommendations in last year’s report. This partially reflects departments having had less than 12 months to implement recommendations included in our 2021–22 reports.

Figure 2F shows the departments with outstanding recommendations.

Notes: DCSSDS – Department of Child Safety, Seniors, and Disability Services; DRDMW – Department of Regional Development, Manufacturing and Water; DSDILGP – Department of State Development, Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning; DTATSIPCA – Department of Treaty, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Partnerships, Communities, and the Arts; DYJESBT–Department of Youth Justice, Employment, Small Business and Training.

Queensland Audit Office using data self-reported by entities.

Some departments provided detailed responses explaining the action they took and the outcomes of those actions. Others provided responses that lacked sufficient detail. For example, the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries clearly outlined the action it had taken to implement recommendations from our report on Effectiveness of audit committees in state government entities (Report 2: 2020–21). It also explained the outcome of its actions, noting improvements in how its audit and risk committee functions. The department also reported that the committee now has a better understanding of the department’s key risks.

We also found instances where the action reported by departments did not align with the status of the recommendation. For example, the Department of Resources reported fully implementing recommendation 11 from Contract management for new infrastructure (Report 16: 2021–22). However, it did not say what it had done, just what it planned to do in the future.

Similarly, the Department of Youth Justice, Employment, Small Business and Training reported fully implementing recommendation 1 from our report Effectiveness of audit committees in state government entities (Report 2: 2020–21). It reported that its audit committee meets frequently, and agenda items reflect the committee’s charter. However, it did not say whether it had reviewed the language and responsibilities in the audit committee charter to clearly define the committee's role, which is what we asked it to do.

Departments need to ensure the action they take fully addresses the recommendations we make.

Note: Figures show the status of recommendations made in 2020–21 and 2021–22 and outstanding recommendations from prior years.

Queensland Audit Office.

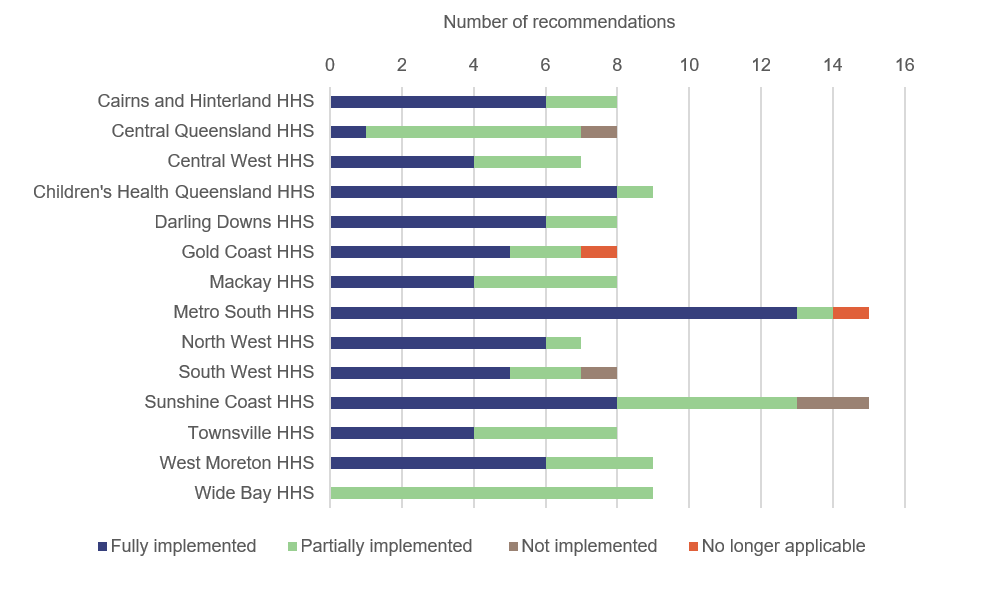

Hospital and health services (HHSs)

We asked 16 HHSs to self-assess their progress implementing 125 recommendations made to them in 2020–21 and 2021–22 and 18 outstanding recommendations from last year’s report. They reported fully implementing 64 per cent of the 143 recommendations.

Metro North HHS and Torres and Cape HHS reported fully implementing all recommendations.

Figure 2H shows the 14 HHSs that reported having outstanding recommendations.

Notes: Gold Coast HHS did not accept recommendation 5 from Planning for sustainable health services (Report 16: 2020–21). North West HHS did not accept recommendation 1 and Central West HHS did not accept recommendation 5 from Measuring emergency department patient wait time (Report 2: 2021–22).

Queensland Audit Office using data self-reported by entities.

In our report Measuring emergency department patient wait time (Report 2: 2021–22), we made 5 recommendations to all 16 HHSs (80 recommendations in total).

Two HHSs did not accept a recommendation. HHSs reported fully implementing 76 per cent (59) of the remaining 78 recommendations, with 23 per cent (18) outstanding. South West HHS reported not implementing recommendation 5 because it does not have short-term treatment areas in its emergency department.

Some HHSs provided detailed responses explaining the action they had taken and the outcomes of those actions. Others provided responses that lacked sufficient detail. For example, Torres and Cape HHS reported fully implementing 4 recommendations from Measuring emergency department patient wait time, but did not explain the actions it had taken. Therefore, we are unsure how the recommendations were implemented.

In contrast, Cairns and Hinterland HHS clearly explained the actions it had taken and the outcome of its actions. For example, it reported fully implementing recommendation 4 from the Measuring emergency department patient wait time report, by implementing the Department of Health’s standardised real-time transfer of care measure. It reported improved performance in emergency department length of stay times.

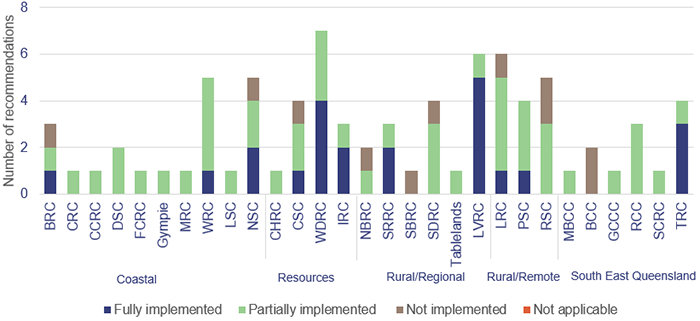

Local governments

We asked 36 local governments (councils) to self‑assess their progress implementing 30 recommendations made to them in 2020–21 and 2021–22 and 57 outstanding recommendations. They reported fully implementing 34 per cent (30) of the 87 recommendations. Seven councils reported implementing all recommendations:

- Gladstone Regional Council

- Ipswich City Council

- Logan City Council

- Mareeba Shire Council

- Rockhampton Regional Council

- Somerset Regional Council

- Townsville City Council.

Twenty-nine councils reported having outstanding recommendations.

Note: Figures show the status of recommendations made in 2020–21 and 2021–22 and outstanding recommendations from prior years.

Queensland Audit Office.

Figure 2J shows the status of recommendations by councils that reported having outstanding recommendations. Councils vary widely in their size and location, and in the range of community services they provide. To enable comparison, we have grouped them into 5 common segments used by the Local Government Association of Queensland: Coastal, Resources, Rural/Regional, Rural/Remote, and South East Queensland.

Note: BRC – Bundaberg Regional Council; CRC – Cairns Regional Council; CCRC – Cassowary Coast Regional Council; DSC – Douglas Shire Council; FCRC – Fraser Coast Regional Council; Gympie – Gympie Regional Council; MRC –Mackay Regional Council; WRC – Whitsunday Regional Council; LSC – Livingstone Shire Council; NSC – Noosa Shire Council; CHRC – Central Highlands Regional Council; CSC – Cook Shire Council; WDRC – Western Downs Regional Council; IRC – Isaac Regional Council; NBRC – North Burnett Regional Council; SRRC – Scenic Rim Regional Council; SBRC –South Burnett Regional Council; SDRC – Southern Downs Regional Council; Tablelands – Tablelands Regional Council; LVRC – Lockyer Valley Regional Council; LRC – Longreach Regional Council; PSC – Paroo Shire Council; RSC – Richmond Shire Council; MBCC – Moreton Bay City Council; BCC – Brisbane City Council; GCCC – Gold Coast City Council; RCC – Redland City Council; SCRC –Sunshine Coast Regional Council; TRC – Toowoomba Regional Council.

Queensland Audit Office using data self-reported by entities.

Councils reported limited progress in implementing our recommendations, particularly those from our series of local government sustainability audits. More than half of the outstanding recommendations come from our sustainability series. It is not surprising that we continue to see recurring issues with councils planning and forecasting, given their lack of progress implementing our recommendations. We made 12 of these recommendations more than 6 years ago. Councils need to prioritise these recommendations to ensure they remain financially sustainable and can deliver essential public services to their communities.

In 2024–25, we plan to undertake an audit on the sustainability of local government. This audit will be the fifth in our series of local government sustainability audits. We will examine councils’ progress in implementing our recommendations from our series, and how they are meeting their sustainability challenges.

We found that some councils provided responses that were inconsistent with the responses they provided last year. For example, North Burnett Regional Council reported last year that it had partially implemented recommendation 7 from our report Managing local government rates and charges (Report 17: 2017–2018). However, this year it reported not implementing the recommendation and outlined the action that it plans to take in the future. Similarly, Richmond Shire Council reported partially implementing recommendation 9 from our report on Managing local government rates and charges last year but reported not implementing it this year. It also explained the action it plans to take going forward.

We also found that Lockyer Valley Regional Council reported that recommendation 3 from our report on Forecasting long‑term sustainability of local government (Report 2: 2016–2017) was fully implemented. However, its response suggests this recommendation is not implemented, as it still needs to engage with its community on future service levels and assess the condition of its assets.

Other entities

We asked other state entities to self-assess their progress implementing 29 recommendations made to them in 2020–21 and 2021–22 and 23 outstanding recommendations from last year’s report.

The entities reported fully implementing 48 per cent (25) and partially implementing 52 per cent (27) of the 52 recommendations.

Many of the outstanding recommendations are from our report on Regulating animal welfare services. We discussed all entities’ progress implementing recommendations from this report in chapter one.

Status of Auditor-General's recommendations dashboard

This Queensland Audit Office interactive dashboard allows you to explore entities’ self-assessed progress based on your area of interest or responsibility. You can search by year, report, entity, parliamentary committee, and implementation status.