Overview

Coal workers are at risk of developing occupational lung diseases from inhaling hazardous dust. As there is no known cure, early detection helps identify individuals who need treatment and to be removed from risk of further exposure. Tabled 5 December 2019.

Audit objective and scope

Objective

In this audit, we assessed how effectively public sector entities have implemented recommendations from the following independent reviews aimed at reducing the risk and occurrence of mine dust lung disease:

- Monash Centre for Occupational and Environmental Health, Review of Respiratory Component of the Coal Mine Workers’ Health Scheme, July 2016 (Monash review)

- Coal Workers’ Pneumoconiosis (CWP) Select Committee reports:

- Report No. 2, Inquiry into the re-identification of Coal Workers' Pneumoconiosis in Queensland, May 2017

- Report No. 4, Inquiry into occupational respirable dust issues, September 2017.

The CWP Select Committee tabled five reports in 2016 and 2017. Reports 2 and 4 are relevant to this audit.

In 2017, the Queensland Government stated that it supported all Monash review recommendations and supported, or supported in principle, all the CWP Select Committee recommendations. The broad range of recommendations relate to the portfolio responsibilities of the Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy (DNRME); Queensland Health; the Office of Industrial Relations; the Department of State Development, Manufacturing, Infrastructure and Planning; the Department of Environment and Science; and the Public Service Commission.

We also assessed how effectively the responsible public sector entities are monitoring and reporting on progress.

This audit also addresses a recommendation from the Monash review to conduct an independent three-year review of the Queensland Government Coal Mine Workers’ Health Scheme.

Scope

DNRME is the government agency responsible for the health and safety of coal mine workers. Most of the recommendations from the three reviews were directed to DNRME (formerly the Department of Natural Resources and Mines), but other entities are also responsible for implementing recommendations.

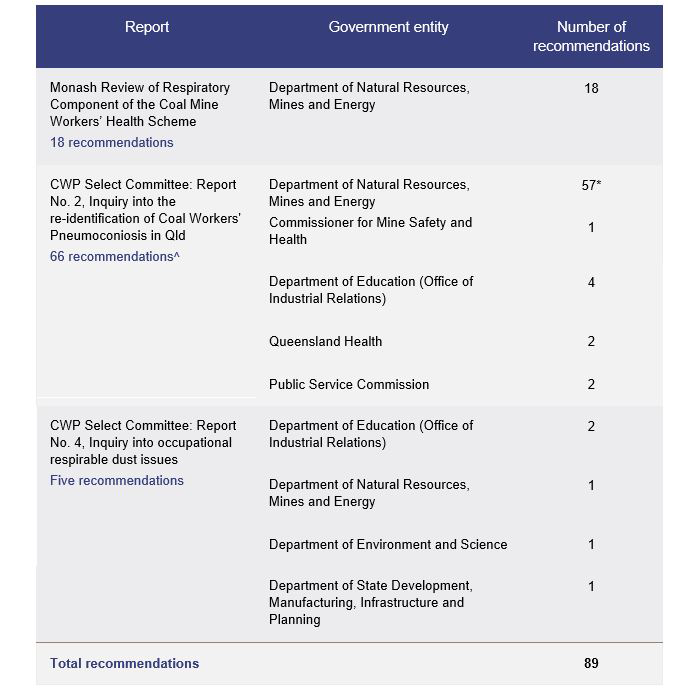

Figure 1 sets out the government entities who share responsibility for implementing the recommendations from the three reports, including the number of recommendations assigned to each entity.

Note: *The project management office developed advice on 19 of the 57 recommendations allocated to DNRME to implement.

^Two recommendations in the CWP Select Committee Report No.2 directed to the Queensland Parliament are out of scope.

Queensland Audit Office.

Of the 68 recommendations made in the CWP Select Committee’s second report, two were addressed to the Queensland Parliament. These recommendations are outside the scope of this audit. We refer to 66 of the committee’s recommendations throughout the report, and a total of 89 recommendations for the three reviews.

We consulted industry representatives and subject matter experts (listed in Appendix B).

The Monash Centre for Occupational and Environmental Health at Monash University contributed to this audit as subject matter experts as they undertook the original Monash review.

Monash University complied with relevant independence policies and procedures, including those required by us, the Queensland Public Service, and the Accounting Professional and Ethical Standards Board. We actively managed any conflicts of interest (actual or perceived) during the audit.

DNRME sought further advice from Monash University after the original Monash review. To mitigate any self-review threat by Monash University, we have precluded Monash’s involvement in assessing those four recommendations.

The audit acknowledges that workers are exposed to occupational dust hazards in a range of industries. However, we have examined the implications only for coal workers exposed to coal dust and silica.

Assessing implementation status

We assessed whether each recommendation has been fully implemented, partially implemented, not implemented (with the recommendation either accepted or not accepted), or is no longer applicable. The definition of each is provided in Figure 2 below.

|

Status |

Definition |

|

|---|---|---|

| Fully implemented | Recommendation has been implemented, or alternative action has been taken that addresses the underlying issues and no further action is required. Any further actions are business as usual. | |

| Partially implemented |

Significant progress has been made in implementing the recommendation or taking alternative action, but further work is required before it can be considered business as usual. This also includes where the action taken was less extensive than recommended, as it only addressed some of the underlying issues that led to the recommendation. |

|

| Not implemented | Recommendation accepted | No or minimal actions have been taken to implement the recommendation, or the action taken does not address the underlying issues that led to the recommendation. |

| Recommendation not accepted | The government or the agency did not accept the recommendation. | |

| No longer applicable | Circumstances have fundamentally changed, making the recommendation no longer applicable. For example, a change in government policy or program has meant the recommendation is no longer relevant. | |

Queensland Audit Office.

We assessed whether entities have taken action in line with government-stated timeframes or otherwise reasonable timeframes based on the nature of the action required, such as changing laws.

Our assessment was based on the actions and time taken by the individual entities who were assigned responsibility by the government to implement improvements. If recommendations have not been implemented, we examined whether decision-making processes were appropriate and whether the issues in the reviews have been addressed through alternative actions.

Reference to comments

In accordance with s. 64 of the Auditor-General Act 2009, we provided a copy of this report to relevant entities. In reaching our conclusions, we considered their views and represented them to the extent we deemed relevant and warranted. Any formal responses from the entities are at Appendix A.

Introduction

For many years, governments in Australia and overseas have acknowledged that mine workers are at risk of developing occupational lung diseases from inhaling hazardous dust.

Disease can be caused by long-term exposure to respirable dust generated during mining and quarrying activities. Onset of disease may occur quickly in circumstances of high exposure or in individuals who are more susceptible to lung conditions. There is no known cure, so early detection helps identify workers who need treatment and need to be removed from risk of further dust exposure.

There are several diseases, collectively called mine dust lung disease. These include:

- coal workers’ pneumoconiosis (also referred to as ‘black lung disease’)

- chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- silicosis

- asbestosis.

Until 2015, coal workers' pneumoconiosis (CWP) was thought to have been eradicated in Queensland. Its recurrence was first identified in 2015 when there were formal reporting requirements in place, but there was no effective way to identify cases of CWP in workers.

DNRME publicly reports confirmed cases of mine dust lung disease. As at 31 October 2019, it reported 116 workers from 2015 to 2019 had been diagnosed with the disease for all mining, including coal, metalliferous, and quarries.

Industry (employers in the end-to-end production of coal), the medical profession, unions, and government regulators all share responsibility for addressing mine dust lung disease.

The independent reviews

A Commonwealth senate inquiry was conducted in 2016 after CWP was formally identified in Queensland. It made several recommendations directed to the Queensland Government and other state governments. Its view was that CWP was a national issue that needed best practice standards of dust control and monitoring to improve health outcomes for workers.

At the same time as the Commonwealth senate inquiry, an independent review (the Monash review) examined the respiratory section of the Coal Mine Workers’ Health Scheme in Queensland. In 2017, the Queensland Parliament established a CWP Select Committee that produced two state parliamentary reports on the subject.

The reports identified multiple gaps in how the coal industry has historically been regulated. They concluded the government needed to improve how it:

- managed coal mine worker medical records

- conducted and monitored compliance activities in mines in relation to the respirable dust hazard

- provided workers with access to adequate medical testing.

The Queensland Government was presented with 91 recommendations aimed at improving the health of coal and other workers. This audit considers 89 of the total recommendations.

The parliamentary inquiries also raised questions about broader health risks for workers involved in the end-to-end production of coal and about other emerging occupational dust lung diseases, such as silicosis. After publicly supporting the reports, the government began implementing the recommendations.

In April 2018, the Queensland Parliament’s State Development, Natural Resources and Agricultural Industry Development Committee asked the Queensland Audit Office to follow up on the government's progress. This audit focuses on mine dust lung disease, but there are broader implications for workers in other industries (such as the engineered stone benchtop industry), who may be exposed to silica dust.

Silica exposure is now recognised as a cancer risk and is considered more harmful to a person's health than coal dust. Coal mine workers can also be exposed to silica as part of coal mine operations. DNRME has collected data that demonstrates coal mine workers are at higher risk of silica exposure than coal dust exposure.

Coal mine workers can access information about the health scheme via the website Miners' Health Matters: https://www.dnrme.qld.gov.au/miners-health-matters or by phone on (07) 3818 5420.

People who have worked in the engineered stone benchtop industry can phone WorkCover Queensland for a free health assessment on 1300 362 128.

Summary of audit findings

The government has made progress in implementing most of the 89 recommendations. Figure 3 summarises our assessment of the current implementation status.

Appendix D details individual recommendations and our assessment of their implementation.

|

QAO assessment |

Monash review |

CWP Select Committee Report No. 2 |

CWP Select Committee Report No. 4 |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Fully implemented |

12 |

20 |

4 |

36 |

|

Partially implemented |

6 |

18 |

1 |

25 |

|

Not implemented (recommendation accepted) |

- |

1 |

- |

1 |

|

Not implemented (recommendation not accepted) |

- |

27 |

- |

27 |

|

No longer applicable |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Total recommendations |

18 |

66* |

5 |

89 |

Note: *Of the 68 recommendations from the CWP Select Committee Report No. 2, two recommendations are out of scope because they were directed to the Queensland Parliament rather than to government entities.

Queensland Audit Office.

Actions taken to date

The government has made important progress in implementing the changes recommended in the reviews to improve coal mine workers' health and safety. As noted in Figure 3 above, work has been undertaken to implement 61 of the 89 recommendations (assessed as fully or partially implemented).

Improving prevention, detection, and rehabilitation

Both the Monash review and the Coal Workers' Pneumoconiosis (CWP) Select Committee recommended changes to the Coal Mine Workers’ Health Scheme to make sure it focused on assessing the health of workers, rather than just their fitness for work.

The Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy (DNRME) has demonstrated significant progress across many aspects of the Coal Mine Workers’ Health Scheme, including providing better access to information for current and former coal mine workers. Through public websites and engagement, it has made information about health and safety easier to access and understand for people working in the industry.

Prevention

Some progress has been made on the CWP Select Committee's Report No. 2, which recommended improvements to dust monitoring and controls. The Select Committee recommended reducing the occupational exposure limit for coal dust and DNRME has published this as an interim measure. But DNRME is waiting for Safe Work Australia to finalise its recommendations for workplace exposure standards before determining whether the coal dust and silica exposure limits will be reduced even further.

The Mines Inspectorate has established a database to collect both coal dust and silica monitoring data to inform prevention efforts. It aggregates the data and then publishes it on its website. This has improved transparency and provided the ability to compare dust levels at all coal mines.

In 2017–18, the Coal Mining Safety and Health Advisory Committee commenced a quarterly review of dust results from the respirable dust database. The review process examines not only dust results, but also the performance of the database itself. In its 2017–18 annual report, the advisory committee reported that the quarterly review of dust results identified a general decrease in the exposure of miners to dust and mine dust exceedances, with average exposure rates and exceedance rates for the year below the requisite levels.

Some reforms to dust monitoring and compliance activities have not yet been fully implemented because they also require detailed consideration by experts and industry.

In addition, after further consideration, DNRME did not accept 12 of the 19 dust monitoring and management recommendations. This means that 12 changes the committee recommended will not be made. In most cases, DNRME could demonstrate that stakeholders and government had been consulted and had agreed that existing arrangements were adequate. But DNRME has not publicly reported where it has made decisions not to implement recommendations. For example, the decision to endorse using real-time dust monitoring devices for compliance purposes in open-cut mines and quarries.

Detection

Many changes have been made, or are about to be made, to the Coal Mine Workers’ Health Scheme. Previously, coal mine workers were required to undertake health assessments on entering the industry and then every five years as a minimum. However, chest x-rays and respiratory function checks were not mandatory. Since January 2017, all miners have had access to free health assessments under the scheme. Mandatory chest x-rays of every coal mine worker are examined against international standards—in both surface and underground mines—every five years.

When miners retire, they can now continue to receive free health assessments every five years (or as frequently as medically advised) for the rest of their life. The free health assessments are also extended to retired mineral mine and quarry workers. This is paid for by DNRME.

To improve the quality of medical examinations, DNRME, in consultation with the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand and the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists, developed new standards and training for physicians who undertake the health assessments. Most recommendations from the Monash review that sought to improve the quality of health assessments for coal mine workers have been substantially completed.

Doctors rely on a number of different screening tests to make a preliminary diagnosis of mine dust lung disease, including chest x-rays, spirometry (to asses lung function), and a medical and occupational history questionnaire. Doctors can refer workers for follow-up tests or referrals to medical specialists while they wait for final x-ray reports, as part of clinical guidelines.

The clinical pathway was approved by the Queensland Chief Health Officer and the Royal Australasian College of Physicians. The guidelines set out a clinical pathway to ensure that workers see the right physicians at the right time if they have an abnormal test result (such as a chest x-ray) or other symptoms. The guidelines assist doctors in reaching a diagnosis of potential cases of mine dust lung disease in a reasonable timeframe. This helps to reduce potential anxiety for workers and their families and provides a more consistent approach.

From July 2016 until March 2019, DNRME sent chest x-rays to Chicago for review by experts (referred to as a ‘dual read process’) to address deficiencies in health screening identified in the Monash review. However, there was a considerable time gap in 2017 and 2018 for workers getting the second read results. We calculated that, on average, it took 195 calendar days (220 median) from the time DNRME sent a chest x-ray to the United States until the date it received a report. DNRME instead measured the number of business days (reporting an average of 141 business days). The data available did not measure the time between the workers’ first chest x-ray and receiving the second read results.

In March 2019, DNRME engaged Lungscreen Australia to conduct the second read of the chest x-rays, instead of sending them to the United States. This considerably reduced the length of time for second reads to weeks not months. Since October 2019, Lungscreen Australia has further improved turn-around times to less than one week for normal chest x-rays. For urgent chest x-rays, DNRME has since reported turn-around time is 1.99 days, but we have not validated this number.

The overall quality of spirometry testing has improved since the Monash review. In September 2019, DNRME received its first quality control report for an accredited spirometry provider, and it was found that this provider was non-compliant. This demonstrates the value of compliance audits and the need to continue auditing all spirometry providers.

Both the Monash review and CWP Select Committee made recommendations that DNRME improve how health data is collected and used to identify early onset of the disease. There is no cure for these diseases, but early detection enables workers to reduce further dust exposure and slow the progression of the disease. DNRME has made progress in collecting and making health data available, but still needs to complete the roll out of its long-term technology solution that will more efficiently analyse coal mine workers' health data. It will allow doctors quick and easy access to patients’ previous health records and facilitate quality control monitoring. The integrated information system is not expected to be operational before October 2020, and some components, such as monitoring population health trends, will not be in place until 2022.

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists acknowledges that coal mine dust lung disease is a preventable disease but relies on comprehensive health surveillance to build on the existing screening program.

To retain the focus on medical health surveillance, rather than on fitness for work, DNRME needs to reconsider the Monash review and CWP Select Committee recommendations to introduce clinical governance over the health scheme. While there is evidence of DNRME consulting with a range of stakeholders, including medical professionals, over the last three years, there has been no designated medical expert or any expert group that has had formal responsibility for overseeing the scheme or to monitor the impact of all the changes over the last three years.

Workers’ rehabilitation and compensation

Improving dust monitoring and reporting helps to support doctors and employers to make decisions to provide safe work environments for workers who are diagnosed with mine dust lung disease.

Like DNRME, the Office of Industrial Relations has conducted many public engagement initiatives to improve awareness among its worker and industry stakeholders about rehabilitation and return to work programs. It is currently developing guidance for employers, insurers, and doctors about what constitutes safe exposure conditions for workers returning to work.

These findings are detailed in Chapter 1.

Addressing broader industry implications

Other coal-related industries

The CWP Select Committee made several comments in its Report No.2 about the need for continued health surveillance for any worker involved in handling or transporting coal (referred to as ‘other coal workers’). It made three recommendations about expanding the Coal Mine Workers’ Health Scheme (administered by DNRME) to provide other coal workers with the free and mandated health assessments that are now accessed by coal mine workers.

In the Select Committee’s extended terms of reference as part of its Report No.4, it affirmed the comments and recommendations made in its second report regarding coal rail workers. While it acknowledged that health risks were low due to the systems in place to reduce workers’ exposure to dust, the Select Committee also noted that it is essential that the health of workers—past and present—be carefully monitored on an ongoing basis that reflects the long latency of mine dust lung diseases.

The government has not implemented these recommendations. The Office of Industrial Relations, in consultation with DNRME, determined that existing work health and safety protections were adequate, and that the risks were different.

While the work health and safety laws do provide safeguards for workers in coal-related industries and allow for all workers to have health assessments, it is only if their employer determines there is a risk to the employee’s health, for example dust exposure risk. But this does not capture other coal workers who have retired.

CWP Select Committee Report No. 4 also recommended the introduction of codes of practice for stevedoring (stevedoring involves the loading or unloading of cargo (such as coal) from a ship) and coal‑fired power stations. The Office of Industrial Relations has successfully implemented both of these codes of practices.

Health monitoring

The CWP Select Committee recognised that the risk of coal dust and silica exposure was not limited to the coal mines. The responsible entities have largely implemented the Select Committee’s recommendations to address the broader industry implications.

Queensland Health has established a register to capture dust lung disease and other occupational respiratory diseases. It is now a requirement that physicians report diagnosed cases of occupational exposure to inorganic dust (for example, silica exposure in the stone benchtop manufacturing industry as well as the mining industry). This provides greater oversight from a health monitoring perspective.

Community impacts

Air quality concerns have been addressed by the Department of Environment and Science after reviewing the positioning of air quality monitoring stations across Queensland. In February 2019, a monitoring station was established in Blackwater and another monitoring station is planned for Emerald by June 2020.

The Department of State Development, Manufacturing, Infrastructure and Planning conducted a review of the planning framework used by local governments to protect communities from dust. They endorsed that the planning framework includes processes and mechanisms for local governments to protect communities from dust and identified actions that will assist local governments to continue or improve their use of these processes.

These findings are detailed in Chapter 1.

Improving industry oversight

DNRME is responsible for regulating mining, land, and water resources in Queensland. The CWP Select Committee, in Report No. 2, concluded that government should separate DNRME's compliance activities (including its Mines Inspectorate) from its responsibility to promote and support the industry. The Select Committee recommended that a new independent regulator and funding model be introduced.

Recognising the complexity of the reforms, the government established a specialist independent project management office to consider some of the Select Committee’s recommendations that proposed structural and funding changes. The project management office engaged with experts, affected stakeholders, and the public, and developed options to guide government's decisions about the most effective model. It delivered its final report to government in June 2018. It was publicly released in February 2019.

DNRME, as the entity assigned responsibility for implementing the new regulatory model, has effectively acted on the project management office's final report and developed a new governance model. The model, now approved by government, effectively meets the intent of the Select Committee to create greater independence and accountability in the industry. However, the final model did not incorporate 11 of the 19 governance recommendations made by the Select Committee (refer to Appendices D and F). DNRME has understandably taken time to consult with all interested stakeholders and to allow government to consider all options.

Despite government approving the new governance model in November 2018, some recommendations from the Select Committee's report are not yet fully implemented. Proposed laws were introduced into Queensland Parliament on 4 September 2019 and have been approved by the Queensland Parliament’s State Development, Natural Resources and Agricultural Industry Development Committee. The bill has not yet been passed. Government also still needs to decide on a long-term funding model for the new regulator.

These findings are detailed in Chapter 2.

Monitoring and reporting implementation progress

In addition to assessing the implementation status of recommendations from the three reviews, we also assessed how effectively the responsible public sector entities are monitoring and reporting on progress.

Communicating status of recommendations

DNRME currently refers to the status of recommendations as ‘actioned’ and ‘implemented’ to describe where:

- action has been taken and the recommendation has been implemented, or

- alternative action has been taken to achieve the intent of the recommendation.

Based on these statements, we expected there to be no further action needed to address the intent of the recommendations.

Since July 2018, DNRME has reported that government has implemented all the Monash review recommendations. DNRME has reiterated the view that it has delivered and/or implemented all Monash review recommendations throughout this audit. This is despite DNRME’s documented advice to government that some initiatives, such as its integrated information management system and chest x-ray audit program, will not be completed until 2020 to 2022.

The Commissioner for Mine Safety and Health has also reported in her annual performance report to government that DNRME has fully implemented the recommendations.

Since July 2019, DNRME's internal status tracker for the CWP Select Committee's Report No. 2 states that 67 of the 68 recommendations are 'actioned/implemented’ and the government has separately reported that it has actioned all the Select Committee recommendations.

Prior to this audit, in 2018, DNRME commissioned consultants to conduct two external reviews to assess the status of the Monash review and the CWP Select Committee report recommendations. The consultants were only asked to consider whether the intent of recommendations had been met through planned actions, rather than whether action had been completed. One consultant report redefined the intent of the Monash review recommendations to match the actions that DNRME had already taken. Despite this, DNRME and the Commissioner for Mine Safety and Health have relied on multiple definitions of ‘delivered’, ‘actioned’ and ‘implemented’ from these consultant reports to report internally and publicly on status.

Appendix E sets out how consistent DNRME and other responsible entities’ reported status of recommendations are compared with QAO’s assessment.

In the absence of consistent, documented definitions of implementation status, DNRME’s current reporting implies there is no further work to be done to fully implement the Monash review recommendations.

The Office of Industrial Relations has not published any status updates related to the Select Committee's Report No. 4.

Decisions to not implement recommendations

In 2017, the Queensland Government publicly stated that it supported all Monash review recommendations and supported or supported in principle all the CWP Select Committee recommendations.

But 27 of the 66 recommendations from the CWP Select Committee Report No. 2 were not implemented due to subsequent decisions by entities or government to not accept them.

Most of the decisions to not implement recommendations were well documented, including through minister or Cabinet approval. In these cases, such as the new independent regulator model, entities demonstrated they had fully considered practical implications, such as funding or operational limitations.

Some recommendations, such as expanding the Coal Mine Workers’ Health Scheme to include other coal workers, impact more than one entity. But the decision not to implement the recommendations were not considered by Cabinet and instead made at department (senior executive) or minister level.

Given that Cabinet has responsibility for developing and coordinating the policies of the government, and that the government had publicly stated its support for all recommendations (including those subject to further consultation), we had expected that Cabinet would have been required to endorse decisions of this nature.

There is no central or public record of information documenting the rationale for not implementing recommendations that were previously supported by government. In the interest of transparency, entities should include this in the public reporting to accurately reflect the government’s positions on the recommendations.

Whole-of-government coordinating and reporting

DNRME, through its minister, has been responsible for continuing to implement the government’s reforms in response to the re-identification of coal workers’ pneumoconiosis. It has responsibility for implementing all the recommendations from the Monash review and most of the CWP Select Committee Report No. 2. In total, DNRME is responsible for implementing 76 of the total 89 recommendations (85 per cent) directed to government.

The Office of Industrial Relations was assigned responsibility for CWP Select Committee Report No. 4.

Given the public interest and independent inquiries held into mine dust lung diseases, we had expected there to be central coordination of the monitoring and reporting of the status of work undertaken by all responsible entities and how much funding has been allocated and spent. But this has not occurred.

Updates have been provided to the Premier for Cabinet briefings and when questions have been raised by parliament or the public. As noted above, progress reports lack consistency due to the use of different definitions by different entities.

These findings are detailed in Chapter 2.

Appendix D details the assessments reported by entities and Appendix E details how these compare to QAO's assessment for each recommendation.

Audit conclusions

In the last three years, the Queensland Government has invested significant time and effort, and committed over $35 million to implementing the recommendations of the three reports from the reviews.

Through effectively implementing or progressing most of the recommendations, the government has improved how it protects the health and safety of coal mine workers and is contributing to reducing the risk of the disease. Most of the actions taken have been timely. Forty per cent of the recommendations have been fully implemented. Twenty-eight per cent of the recommendations are in progress (partially implemented) and are on track to meet the intent of the recommendations. The government initially supported, or supported in principle, all recommendations, but nearly one-third (31 per cent) of recommendations have since not been accepted and not implemented.

There is still work to be done to deliver all the reforms. This includes establishing an independent regulator and funding model and developing criteria to assist those responsible for ensuring workers can return to work. DNRME is also currently developing new information systems to detect early signs of work-related health issues that can be used for mine inspections, audits, and implementing better health and safety controls.

As the entity responsible for implementing most of the recommendations, DNRME has dedicated significant resources to progress the work. In some cases, such as establishing a new governance model, it is waiting on the outcome of government processes to introduce new laws and regulations and approve budgets. However, after three years, some of the recommendations have still not been implemented, for example some changes to dust monitoring practices and health assessments have not been finalised.

The Office of Industrial Relations successfully introduced codes of practice for stevedoring (stevedoring involves the loading or unloading of cargo (such as coal) from a ship) and coal‑fired power stations. It has commissioned expert medical advice to provide recommendations about returning workers to a mine site with a diagnosis of CWP or coal mine dust lung disease. This advice will form the basis of guidance to assist treating specialists, mining employers, and workers diagnosed with mine dust lung disease in returning to work.

The entities responsible for implementing a smaller number of recommendations—Queensland Health; the Department of State Development, Manufacturing, Infrastructure and Planning; the Department of Environment and Science; and the Public Service Commission—have effectively implemented the recommendations from the Select Committee.

The three reports all saw government creating a more integrated approach to addressing coal mine workers' health and safety. But the lack of shared, agreed definitions across the entities responsible for recommendations has resulted in a variety of terms being used such as 'fully actioned' or 'implemented' or 'delivered'. This means there is no clear, accurate reporting on the status of the work. There is also no collective view or monitoring across all responsible entitles of how much government has spent on implementing the reforms—despite committing $35 million.

Given the number of recommendations that still need to be fully implemented, and emerging related health issues (such as silicosis), responsible entitles should be providing complete and comprehensive reports to one agency to monitor the remaining work program and keep a record of decisions not to implement recommendations.

1. Prevention, detection, and support

Introduction

The Monash University Centre for Occupational and Environmental Health, in collaboration with the University of Illinois, Chicago, published the Review of Respiratory Component of the Coal Mine Workers’ Health Scheme (the Monash review) in 2016. The review found the respiratory component of the Coal Mine Workers’ Health Scheme focused on fitness to work rather than on detecting and managing early mine dust lung disease. It also found several limitations, including that health information was not being effectively used to monitor trends in mine dust lung disease (referred to as ‘group health surveillance’).

The Monash review recommended that the Queensland Government introduce a range of reforms to improve chest x-rays, lung function testing (called spirometry), training and accreditation of medical practitioners, surveillance, and digital records management.

The Coal Workers’ Pneumoconiosis Select Committee (Select Committee) agreed with the Monash review and identified additional limitations in its Report No. 2 (Inquiry into the re‑identification of Coal Workers' Pneumoconiosis in Queensland) about how the Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy (DNRME) was administering the Coal Mine Workers’ Health Scheme. Its report referred to:

- Those tasked with monitoring the health of Queensland coal workers were not actively looking for the disease, and in many cases were insufficiently informed and ill-equipped to enable its diagnosis.

- The role of the Health Surveillance Unit at DNRME was purely administrative, with no meaningful data analysis or clinical review being undertaken of the health assessment records it received. This was contrary to the policy objectives of the health scheme, which were to monitor and ensure the health of coal mine workers.

The Monash review and the Select Committee both commented on the large backlog of health assessments that DNRME was processing at the time of their respective reports. The Select Committee supported the Monash review recommendations.

In terms of preventing and monitoring risks of dust lung disease and supporting workers' return to work, the Select Committee also found:

- Coal mine operators did not have clear or consistent guidance from inspectors about actions required to demonstrate dust monitoring compliance, and the industry developed a culture of complacency and disregard for the serious risk posed by respirable dust exposure.

- Before legislative changes were introduced in January 2017, there was an absence of any regulated oversight of respirable dust monitoring or mandatory reporting of dust exceedances.

- The primary focus of the regulator, DNRME, was on mine safety, rather than on miners' health and the risks posed by exposure to respirable dust. Of the range of compliance options that the Mines Inspectorate can use, the Select Committee’s report noted that no person or entity had been prosecuted in Queensland for failing to meet a safety and health obligation related to respirable dust.

Refer to Appendix G for summary of key findings and recommendations from the Monash review and the CWP Select Committee reports.

This chapter assesses whether entities have effectively reduced the risk and occurrence of mine dust lung disease. It also assesses the effectiveness of arrangements to support workers' return to work.

Appendices D and E contain the complete list of recommendations and our assessments.

Dust monitoring and controls (prevention)

Of the 66 in-scope recommendations made in the Select Committee Report No. 2, 19 recommendations focused on dust monitoring and management.

The recommendations related to:

- improving respirable dust monitoring and management (13 recommendations)

- improving the enforcement and oversight of coal dust management (six recommendations).

Figure 1A summarises our assessment of the current implementation status for recommendations about dust monitoring and controls.

|

QAO assessment |

Select Committee Report No. 2 |

|---|---|

|

Fully implemented |

4 |

|

Partially implemented |

2 |

|

Not implemented (recommendation accepted) |

1 |

|

Not implemented (recommendation not accepted) |

12 |

|

Total |

19 |

Note: For QAO's detailed assessment of each recommendation, refer to Appendix D. For the government's response and status of implementation for each recommendation, refer to Appendix E.

Queensland Audit Office.

Progress made

Dust monitoring and management practices

Coal dust occupational exposure limits

The Select Committee recommended reducing the occupational exposure limit for coal dust to 1.5mg/m3 of air. At the time, the government, in consultation with DNRME, decided not to adopt these limits until Safe Work Australia released its final limits.

In November 2018, the government reduced the limit for coal dust from 3.0 mg/m3 to 2.5 mg/m3 as an interim measure while Safe Work Australia undertook a review of airborne contaminants including coal dust and silica.

In February 2019, Safe Work Australia proposed a draft coal dust limit of 0.9 mg/m3 and invited public consultation on the draft limits.

DNRME is consulting with industry about the potential impacts of the reduced limits expected in Safe Work Australia's final report in March 2020. Safe Work Australia’s current proposal is that the occupational exposure limit for respirable coal dust be reduced to 1.5 mg/m3. On 18 September 2019, the Minister for Natural Resources, Mines and Energy confirmed Queensland’s support for this proposal.

Encouraging miners to report safety issues

The Select Committee recommended that coal mine workers be encouraged to report safety issues. Since the report, we note there is a heightened focus by DNRME, industry, and union stakeholders to encourage miners to report safety issues. This focus has been renewed again following recent fatalities in Queensland mines.

The Commissioner for Mine Safety and Health (the commissioner) has actively promoted that: 'It is an offence to cause detriment to another person because they have made a complaint or have raised a mine safety issue’. The commissioner regularly visits mine sites and attends industry forums to communicate this message.

The government, industry, and unions agree this is an area that requires continuous focus to encourage a culture that accepts the reporting of health and safety issues. While the commissioner accepts anonymous complaints, reporting processes are not equivalent to whistle-blower protections for workers.

Reporting dust exposure data

Dust monitoring database

The Select Committee recommended DNRME establish a database to collate dust monitoring data collected across mine sites to improve its monitoring of dust exposure limits.

Since 1 January 2017, all Queensland coal mine operators have been required to provide quarterly reports to DNRME's Chief Inspector of Coal Mines on the results of their respirable dust monitoring. They must also report when dust levels exceed occupational exposure limit levels set in regulation.

The Mines Inspectorate has established a database to collect both coal and silica monitoring data. Examples of DNRME’s dust monitoring reports are included in Appendix H. It aggregates the data and then publishes it on its website. This has provided improved transparency and the ability to compare dust levels at all coal mines. DNRME presents quarterly data to the Coal Mining Safety and Health Advisory Committee for review, and briefs government on dust monitoring results. In its 2017–18 annual report, the committee reported that this quarterly review of the dust results has identified a general decrease in the exposure of miners to dust and dust exceedances, with average exposure rates and exceedance rates for the year below the requisite levels.

However, there is an opportunity to increase the level of information shared with industry about dust monitoring data to improve dust monitoring and mitigation technologies. Industry stakeholders reinforced this view during the audit. They noted that there are opportunities to share best practices if there is greater exchange of information about data sampling results and methodology, including examples of engineering practices that have effectively reduced dust exposure risks. There are also opportunities to more strategically monitor emerging health risks and guide compliance activities, such as audits and inspections.

In 2016–17, the commissioner reported that the database is used to inform quality control measures at work group, mine, and operator levels. This may be happening in some places, but we did not see evidence of the database being used in this way during the audit.

What still needs to be done

Dust monitoring and management practices

Silica occupational exposure limits

In addition to addressing coal dust limits, the Select Committee recommended reducing the occupational exposure limit for silica to 0.05mg/m3 of air. The government decided not to adopt these limits until Safe Work Australia released its final limits.

Workers can be exposed to silica dust as well as coal mine dust while working in coal mines. It is referred to as ‘respirable crystalline silica’, and can lead to silicosis, which is another occupational dust lung disease. Silica is considered more toxic than coal mine dust, so exposure limits are lower.

In Queensland, the workplace exposure standard for silica in coal mines is 0.1 mg/m3. The government is waiting for the final outcomes of Safe Work Australia's review until it revises its silica limit.

Safe Work Australia’s proposed silica limit is 0.02 mg/m3 for all industries, including coal mines. The government, industry, and trade unions have reported concerns about adopting Safe Work Australia's proposed limit for silica, because it will be difficult to effectively implement, monitor, and enforce. This is, in part, because the available technology is not able to detect or record dust particles at that level.

Safe Work Australia’s final report is expected to be released in March 2020. At the time of this report, it has not made a final decision on what limits it will accept.

Real-time personal dust monitors

There are still outstanding actions regarding the use of real-time personal dust monitors.

Current dust monitoring tools for coal and silica dust require samples to be sent to laboratories for analysis. On average, it takes 14 days for coal mine operators to receive these results. This means that workers are not immediately aware when they have been exposed to high levels of hazardous dust and it is difficult for mine operators to quickly adjust processes or workers' positioning in response to high levels of exposure. This also impacts the effectiveness of return to work programs for workers who have been diagnosed with mine dust lung symptoms and need to constantly monitor their exposure to dust.

Real-time personal dust monitors can be used to monitor individual workers’ exposure to occupational dust in above-ground coal mines. In underground mines, they can only be used in limited circumstances due to safety reasons.

DNRME publishes minimum standards to mine operators outlining ways to effectively manage risks at coal mines. Operators can manage risks in different ways, but must be able to show that the method they use meets the minimum standards.

DNRME has a standard for monitoring respirable dust in coal mines. It stipulates that mine operators' dust samples must be collected using monitoring equipment and techniques according to Australian standards. DNRME also requires samples to be analysed in an accredited laboratory.

DNRME’s standard currently prevents mine operators from using real-time personal dust monitors for compliance sampling. This is because real-time monitors do not meet the national standard. The standard was published in 2009 and does not reflect the current technology of real-time personal dust monitors, or emerging technologies for silica dust.

An industry working group explored the use of real-time personal dust monitors and presented its work on three separate occasions to the Coal Mining Safety and Health Advisory Committee (made up of industry, trade unions, and government).

On 29 November 2017, the advisory committee voted unanimously to amend the standard to allow the use of real-time monitors for compliance monitoring purposes in open-cut mines. It separately acknowledged the safety issues involved with using real-time monitors in underground mines.

The outcomes of the advisory committee's decision were provided to the minister to be endorsed. DNRME issued a revised version of the standard in November 2018, but it was not amended to reflect the advisory committee’s decision. At the time of reporting, DNRME did not have confirmed advice from the minister to implement the advisory committee’s decision.

Enforcing and overseeing coal dust management

The Select Committee recommended that DNRME's Mines Inspectorate significantly increase its dust monitoring activities.

Since 2017, the government has allocated nearly $5 million to improving dust monitoring, reporting, and assessment. This includes $1.68 million in the 2019–20 budget for additional occupational hygiene capability.

Inspecting dust controls and exposure levels

Mine operators must adhere to DNRME's standard for controlling respirable dust in underground coal mines—separate from monitoring dust. The Coal Mining Safety and Health Advisory Committee has been developing an equivalent standard for open-cut mines since September 2018.

DNRME's Mines Inspectorate performs inspections of mine sites to identify potential risks, harms, and other compliance issues. Inspections are part of DNRME's regular ongoing compliance activities that look at all aspects of a coal mine's operations.

When inspectors are undertaking an inspection, they follow DNRME's inspection guidelines. Currently, the inspector has discretion as to whether they include dust as part of their inspection of underground mines. This is because the database is not set up to make dust (occupational hygiene dust monitoring) a mandatory component of the inspection guidelines. If an inspector does consider dust, there are no minimum requirements they must address in their inspection.

Results of mine inspections are entered into a database. QAO’s examination of the database found that:

- Examples of some recent inspection reports from underground mines (mine record entries) did not include respirable dust as part of the inspection.

- DNRME has no way to efficiently extract information from their inspections database to determine the number of coal mine inspections that considered control of respirable dust, or the extent to which it was considered.

- Mine reports are in free-form text format, so there is no accurate or consistent way to report on the number of coal inspections and audits related to dust.

- It is difficult to conduct analysis of emerging compliance themes at a system level.

We note that the equivalent system used for mineral mines and quarries includes structured guidance notes about relevant laws and regulations and requires hazard factors, such as dust and silica, to be addressed.

Figure 1B demonstrates the reduction of inspections since 2015, noting that this is not specifically for silica or coal dust—rather all inspections that have been conducted for coal mines. The minister has separately reported through parliament in July 2019 that the number of inspections has reduced due to DNRME’s increased focus on coal workers’ pneumoconiosis and investigating recent fatalities.

It also demonstrates the increase in audits at the same time as the reduction of inspections. From 2018, there have been 15 dust monitoring audits undertaken.

|

Financial year |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

All inspections |

397 |

396 |

375 |

364 |

|

Announced inspections |

382 |

379 |

341 |

293 |

|

Unannounced inspections |

15 |

17 |

34 |

71 |

|

All audits |

4 |

8 |

44 |

61 |

|

Audits (dust monitoring) |

0 |

0 |

8 |

7 |

|

Audits (not dust monitoring) |

4 |

8 |

36 |

54 |

Note: The total number of inspections includes all coal mine inspections, but not all inspections necessarily include a dust element. The total number of audits (all hazards) do not include a dust element. Only 15 audits were specific to dust monitoring.

Queensland Audit Office.

Auditing dust controls and exposure levels

DNRME’s Mine Inspectorate carries out audits of coal mines to assess whether mine operators are complying with industry minimum standards related to health and safety systems. Audits are more in-depth than inspections.

In 2017, DNRME developed an audit guideline to help its inspectors assess whether mines are complying with its standard for monitoring respirable dust. The guideline ensures dust monitoring audits are conducted consistently.

Four inspectors are qualified as occupational hygienists who can conduct dust monitoring audits. However, only one inspector conducts targeted audits for coal mines. The other inspectors work across mineral mines and quarries.

There are currently 52 open-cut and 11 underground coal mines operating in Queensland. Since 2017, DNRME has conducted 15 audits of open-cut mines to determine how well mine operators have established a program to monitor dust. During these 15 audits, DNRME did not examine whether coal dust or silica exposure levels were being effectively monitored. No audits have been completed for underground mines.

In September 2019, the minister, through parliament, reported that the actual number of audits of coal mines have not matched planned audits for the last two years.

Recommendations not accepted

Dust monitoring and management practices

Dust abatement and ventilation plan

The Select Committee recommended Queensland adopt a similar model to New South Wales for dust abatement and ventilation plans. In New South Wales, coal mine operators are required to obtain approval of these plans prior to starting mine operations to demonstrate how they will proactively manage dust. There is no equivalent process in Queensland.

DNRME presented an options analysis to the Coal Mining Safety and Health Advisory Committee in September 2018. The advisory committee did not support dust abatement plans. Instead, it proposed that DNRME develop a new standard for dust management in open-cut mines to supplement existing legislation and standards. At the time of the audit, DNRME advised the standard was anticipated to be gazetted for notice on 29 November 2019.

The Coal Mining Safety and Health Act 1999 was separately amended to impose civil penalties for non-compliance with existing legislative provisions for dust management.

Commercial dust monitoring providers

The Select Committee recommended separating mining operators from private occupational hygiene providers (who conduct dust sampling) to reduce the risk of conflicts of interest. This has not happened.

DNRME has not implemented a recommendation for private occupational hygiene providers to submit results directly to the Chief Inspector of Coal Mines. Coal mine operators are required to report exceedances and quarterly monitoring results to the Chief Inspector of Coal Mines, but this does not address the committee's concern about maintaining the integrity of results.

The Coal Mine Safety and Health Advisory Committee endorsed mandatory competencies for those who conduct respirable dust sampling. This enables mining operators to conduct their own sampling once accredited, which is contrary to the committee's intent.

Standing dust committee

The Select Committee recommended that an independent committee be established to review dust monitoring results and trends. In September 2017, the Coal Mining Safety and Health Advisory Committee advised that a standing dust committee was not required, as it already fulfilled the role. The minister endorsed the recommendation in November 2017.

The advisory committee is of the view that respirable coal dust is now well managed and monitored. In its 2017–18 annual report, the committee reported that its quarterly review of dust results has identified a general decrease in the exposure of miners to dust and dust exceedances, with average exposure rates and exceedance rates for the year below the requisite levels.

Despite the Select Committee's recommendation, the advisory committee does not currently include representatives from coal ports or people independent of the mining industry that might be impacted by coal dust or silica.

Enforcing and overseeing coal dust management

Mines Inspectorate

One of the Select Committee’s key findings was that DNRME’s dust monitoring inspections and audits of dust sampling results from mine operators were not adequate to provide the public and workers with confidence in the integrity of that system. It raised concerns of flawed sampling practices, including non-representative samples. It reported that most sampling activities were conducted during production shifts rather than during scheduled or non-scheduled maintenance. It also reported on the high rates of samples being voided, suggesting that high-level samples (samples that return a high read of dust exposure) were being interfered with.

DNRME decided not to implement the recommendation for mines inspectors to observe coal workers during periods of atmospheric monitoring (air monitoring of a specific space) or to validate dust monitoring results.

In addition, the Select Committee’s concerns about regulatory capture (where regulatory entities favour industries’ perspective) have not been addressed. DNRME decided not to implement the recommendation to amend regulations to prohibit mines inspectors from inspecting mines where they have previously worked. It also does not have a documented policy. However, the Commissioner for Mines Safety and Health has reported that the department does have a strict internal policy on this in place.

The reasons for DNRME not implementing the recommendation are set out in Appendix D.

Unannounced visits by industrial safety and health representatives

The Select Committee recommended that DNRME permit more unannounced inspections from industrial representatives to strengthen its existing compliance program.

DNRME decided not to implement the recommendation to remove 'reasonable notice' for industrial safety and health representatives due to a lack of demonstrated tripartite support during a separate inquiry.

DNRME has noted that mine sites are hazardous by nature, with strict health and safety induction processes that must be completed prior to entering a site.

Health assessments (early detection)

In total, there were 38 recommendations about improving respiratory health monitoring to detect mine dust lung diseases for coal workers.

All 18 recommendations from the Monash review focused on changes to the Coal Mine Workers' Health Scheme.

The Select Committee made a further 20 recommendations, including recommendations on improving health arrangements for coal workers.

Figure 1C summarises our assessment of the current implementation status for recommendations directed towards improving health assessments for coal workers.

|

QAO assessment |

Monash review |

Select Committee Report No. 2 |

|---|---|---|

|

Fully implemented |

12 |

12 |

|

Partially implemented |

6 |

6 |

|

Not implemented (recommendation not accepted) |

- |

2 |

|

Total |

18 |

20 |

Queensland Audit Office.

Progress made

Improved respiratory health arrangements for coal mine workers

Both the CWP Select Committee and the Monash review recommended that DNRME amend its Coal Mine Workers’ Health Scheme to ensure it focused on assessing health, rather than just assessing fitness for work. The recommendations included improving workers' awareness of risks and support services.

Focusing on health

Over the last three years, DNRME has considerably improved health arrangements for coal mine workers. The progress made to date includes:

- extensively consulting stakeholders through discussion papers on roles and responsibilities for the scheme

- expanding the scheme to provide early diagnosis and intervention for respiratory diseases

- providing coal mine workers with access to exit respiratory health assessments (conducted when they leave the job)

- offering health information through websites and roadshows and continued health assessments for retired and former coal mine workers on a voluntary basis.

However, DNRME does not currently have a dedicated occupational physician to oversee the scheme as recommended by the Select Committee.

Access to information for coal workers and employers

DNRME has successfully built an effective communication network to connect with coal mine workers. It has consulted with coal mine operators, site senior executives, union leaders, and site safety and health representatives to help disseminate general awareness information at mine sites.

It has created a dedicated website and communication materials to improve the information available to miners and employers on coal mine dust lung disease. The website is clear and well presented. Examples of what it provides include:

- videos for coal mine workers about preventing and detecting lung disease, and about support services

- factsheets for workers with contact email and telephone

- information booklets designed to fit in a miner’s pocket, addressing dust exposure in coal mines and mine dust lung disease

- a Miners' Health Matters website, which was launched in June 2018.

There is also online information available for retired or former coal mine workers. Despite all these improvements, stakeholders, including industry and advocacy groups, noted during the audit that there are more opportunities for DNRME to use local community networks such as retired worker associations, general practices, and sporting and other membership groups. This would ensure that support services and advice are effectively communicated in other forums for workers and their families who may not otherwise access information online.

Integrated information management

DNRME's Health Surveillance Unit is responsible for managing coal workers’ health records. At the time of the Monash review, DNRME had over 170,000 hard copy files in storage.

DNRME has identified that their current systems do not provide doctors with timely and simplified access to a coal mine worker’s previous work history or health assessment records to gain a long-term view of worker health to detect any significant decline over time.

DNRME has advised its minister that:

- Given the recommendations of the Monash review to undertake health surveillance, DNRME will need to enhance existing systems in the Health Surveillance Unit (HSU) to ensure the long-term solution delivers adequate data (expected in 2021–22).

- Due to the limited utility of the existing HSU database, health surveillance capability is severely restricted without enhancing existing systems.

The Monash review and CWP Select Committee Report No. 2 made five recommendations that rely on DNRME moving to a new electronic information management system. It would:

- assist doctors to enter results of health assessments and access historical health records to improve the time and accuracy of potential diagnoses

- allow DNRME to audit the quality of medical health assessments

- facilitate regular and meaningful surveillance to identify trends in disease, inform policy decisions and identify regional areas or individuals

- assist in disseminating analysis and trends to employers, unions, and coal mine workers

- permit DNRME to register and authorise clinicians.

Prior to release of the Monash review, as an interim measure, DNRME began scanning hard copy health record files into an electronic format. By June 2017, it had completed a substantial amount of work over 18 months to scan 174,288 chest x-rays, spirometry reports, and health assessments.

The backlog has now been resolved, but there is an ongoing requirement for DNRME to continue to scan health records. In 2018–19, 40 per cent of health assessment records were still provided by doctors in hard copy. Since July 2019, DNRME has received 88 per cent of health assessment records in electronic format. These scanned health assessments still require DNRME’s staff to manually enter them into the HSU database.

If doctors request access to a worker’s previous health records, it can take five days for DNRME to release them. While we acknowledge DNRME’s time and resourcing in addressing the backlog, the scanning of health records does not fulfil the intent of three of the Monash review recommendations or two of the CWP Select Committee’s recommendations.

In 2018, DNRME identified that there were broader business requirements necessary to implement the Monash review recommendations and CWP Select Committee recommendations. It reported that a new technology solution was urgently required to support coal workers and alert them of any new diagnosis of potential or identified disease. It was also noted that the system must provide DNRME with the required access to health record statistical data to enable surveillance reporting, identify trends in disease, and inform policy decisions.

In DNRME project documents approved in March 2019, the department noted multiple problems with the current records management system including:

- medical practitioners cannot quickly access previous health assessments to gain a historical long-term view of worker health

- coal workers cannot quickly access their health records, including when they leave the industry or move interstate

- health data is not readily available for surveillance purposes, including to detect early trends of mine dust lung disease

- there are risks of inaccurate data due to manual entry of health assessments

- inefficient data storage requirements.

Separate project documents approved in April 2019 state that the proposed new digital occupational health surveillance solution will support DNRME in its role in administering the Coal Mine Workers’ Health Scheme. This will be achieved by integrating several stand-alone technology systems and its largely paper-based records management system.

DNRME received over $3.9 million funding in 2017–18 to establish the system, and an additional $1.1 million in 2018–19. DNRME has advised that the system is expected to be operational by October 2020 (but it will not deliver group health surveillance capability until 2021–22). Once fully implemented, the system is expected to:

- digitally capture fitness for work health information from employers, workers, and clinicians

- provide electronic worker assessment information storage

- provide appropriate access to previous assessment records by medical practitioners, employers, coal workers, and others

- enable data analysis and reporting over collected health assessment data to support regular and meaningful surveillance

- provide for clinical data exchange with other health management systems.

When commenting on DNRME’s proposed electronic records management project, the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists noted that ongoing health surveillance and screening will ensure holistic management of coal mine workers’ dust lung disease.

DNRME has started to develop its research strategy, including co-funding a dust disease research study with the Wesley Hospital to analyse and report on trends such as age, gender, work history, disease severity, and smoking status. It is also exploring other research partnerships to address cancer and mortality trends in coal mine workers.

DNRME’s position is that its current state of transitioning to the new system meets the intent of the Monash review and has reported that the recommendations are fully implemented. However, until there is an integrated information system fully functioning, we consider that these recommendations are partially met.

Training and selecting doctors

Doctors play an important role in assisting workers to reduce their further exposure to dust.

The Monash review recommended that doctors performing health assessments for coal mine workers be appropriately trained and qualified, in order to improve prevention and detection of diseases.

DNRME has strengthened how doctors are selected and trained to be able to participate in the Coal Mine Workers’ Health Scheme. From 1 March 2019, only doctors approved by DNRME can undertake health assessments under the scheme. Once approved, doctors are referred to as ‘supervising doctors’. They are then contracted by coal mine operators as ‘appointed medical advisers’ (AMAs). The AMA's role is to carry out and report on health assessments for the employer's coal mine workers. They also supervise other doctors who are not AMAs but who are authorised to perform medical examinations of workers.

DNRME has introduced new training programs for doctors about how to consider dust exposure controls when performing health assessments of coal mine workers. The doctors are provided with training on:

- assessment of past exposure

- descriptions of types of mines and jobs

- sources of coal mine dust and the control measures.

With the assistance of our subject matter experts, Monash University, we reviewed 236 health assessment forms against the Thoracic Society Australia and New Zealand Standards—Delivery of Spirometry for Coal Mine Workers July 2017. The review identified that there are still opportunities for DNRME to improve doctors’ training. These areas include ensuring doctors accurately complete health assessment forms and providing better guidance to support workers returning to work.

The areas of improvement from the health assessment forms were provided to DNRME to investigate. DNRME reviewed the same sample and identified five individuals where the clinical pathway was not followed.

Chest x-rays

The Monash review identified concerns about the quality of Queensland chest x-ray reports to accurately diagnose mine dust lung disease for coal mine workers. At the time of their report in 2016, there were limited specialist radiologists in Australia.

Dual read process

Doctors use chest x-rays to identify early signs of occupational dust lung disease. Best practice is for chest x-rays to be reviewed twice (referred to as a ‘dual read process’) by a minimum of two radiologists. These radiologists undertake additional training to be qualified and are called B-readers (second reads). Qualified B-readers review chest x-rays according to an international classification standard (International Labour Office, ILO).

The United States of America’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) offers a one‑week training course for specialist medical practitioners (radiologists, occupational physicians, and respiratory physicians) to report chest x-rays using the internationally recognised standards. Physicians who have passed this course are referred to as ‘B-readers’.

The University of Illinois, Chicago, is engaged by DNRME to deliver training for Australian doctors who are registered to perform coal mine worker health assessments.

Timeliness of x-ray results

It was positive to note that most chest x-rays we examined (168 of the 234 where dates were noted) were taken within a day after the initial health assessment, and these chest x-rays were provided to the doctor within a time period of a few days to a few weeks.

To address the concerns raised in the Monash review, from late 2016 DNRME started sending coal mine workers' chest x-rays for screening to a recognised expert at the University of Illinois, Chicago, for a second read. The government has spent $7 million to date to do this.

During 2017 and 2018, there was a considerable time gap between when chest x-rays were taken and when the final reports were received from Chicago. We calculated that, on average, it took 195 calendar days (220 median) from the time DNRME sent a chest x-ray to the United States until the date it received a report. For the same period, we note that DNRME reported that it took on average 141 days to receive the final report, as they measured business days as opposed to calendar days.

Where a worker presented with abnormal results from preliminary tests, such as from a chest x‑ray, doctors were able to refer the worker for follow-up investigations and referrals to medical specialists while they waited for the final chest x-ray report (referred to as the ‘clinical pathway’). DNRME issued clinical pathway guidelines in 2017 to assist doctors in reaching a diagnosis on potential cases of coal mine dust lung disease in a reasonable time frame. This aimed to reduce worker anxiety and provide more consistent outcomes.

Doctors also had the option of requesting a priority read—this process aimed to have results returned from the United States within three months for urgent requests.

We noted in a small number of workers that the first read did not identify any abnormalities, and the second read did. For these workers, the delay in receiving the final report may have meant a lost opportunity to take early action to reduce further dust exposure. However, in most cases there has been strong agreement between read results from the first read by Australian radiologists and the dual read results from the United States.

From 1 March 2019, DNRME engaged Lungscreen Australia to conduct all second readings instead of sending them to the United States. This has shortened the time period considerably. When we examined x-rays performed since March 2019, we found almost all second reads were completed from between a few days to a few weeks. As at October 2019, Lungscreen Australia has further improved turn-around times to less than one week.

Final health assessments are only completed once all tests have been undertaken, including second read chest x-rays and spirometry. Doctors are required to provide timely feedback to coal mine workers on the outcome of their health assessments under clinical guidelines issued by DNRME. When coal mine workers receive the report, they are required to sign the health assessment to acknowledge that they have discussed the report with the doctor.

DNRME advises that AMAs are often not the examining doctor and they only perform a review of a worker’s health assessment without actually seeing the worker in person. This is consistent with our examination of the 236 completed health assessments, where we found worker signatures (confirming advice from the doctor) on 20 of them.

The Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union (the union) advised that if workers do not agree with a diagnosis or return to work conditions, the worker will not sign the medical forms. The clinical guidelines state that miners can submit a further medical health assessment from a doctor of their choice. AMAs are required to advise employers of the outcomes of health assessments of employees. But DNRME has no process to ensure that the AMA has notified the employee. DNRME advises that it relies on the professional integrity of the medical provider to answer these questions accurately.

Quality standards

In September 2017, DNRME released its standard for digital chest x-ray images for Queensland coal mine workers. It sets out:

- quality standards for medical officers who take chest x-rays (including image quality)

- qualification requirements for medical officers who report the chest x-rays (including that they must complete the international B-reader program).

In December 2017, 13 Australian B-readers were qualified. From then, a transition process was in place until Lungscreen Australia replaced the Chicago-based B-readers on 1 March 2019. Registration lasts for four years and B-readers need to re-sit examinations periodically to keep their qualifications current.

To monitor the quality of chest x-rays, DNRME:

- engages a third party, Quality Innovation Performance, to accredit chest x-ray providers prior to applying for registration with the department as an approved provider

- receives reports from Lungscreen Australia about the quality of chest x-rays taken by registered chest x-ray providers (this includes rejecting poor quality images).

DNRME has also engaged the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) to review the quality of x‑ray imaging and reporting. This will occur once UIC completes the 100 per cent audit phase later in 2019/early 2020.

Spirometry

In addition to chest x-rays, doctors use spirometry tests to measure a person’s lung function. Specialist laboratories and medical clinics conduct the tests. The Monash review recommended that spirometry testing should be consistent with current Australian standards. It also recommended that the quality of tests be audited regularly as part of the overall auditing within the Coal Mine Workers' Health Scheme.

Spirometry test results

With the assistance of our subject matter experts, Monash University, we reviewed 228 completed health assessments conducted up until April 2018. We assessed whether the quality of the spirometry tests had improved and whether previous results were recorded to allow tests to be compared.

We found the quality of spirometry tests has improved:

- Nearly 90 per cent were considered acceptable quality compared to 60 per cent at the time of the Monash review in 2016.

- The accuracy of results had increased from 79 per cent to 86 per cent.

- Only one assessment had no spirometry data.

Our subject matter experts also identified a proportion of tests that only had automatically generated quality comments from spirometry software. High-quality spirometry testing is vital for accurate interpretation. While many spirometry testing software programs generate these assessments, a preferable approach is for operators to make their own specific comment indicating their interpretation of test quality and relevant patient information.

Training and accrediting spirometry providers