Overview

Fifty large entities in the Queensland Government deliver energy, health, ports, water, and rail services throughout the state. Their boards provide strategic direction and ensure their entities conduct themselves in an accountable and transparent manner. Therefore, it's important that board members with the right skills are appointed within a reasonable time frame and are fairly remunerated.

Tabled 19 May 2022.

Report on a page

There are 50 large Queensland government entities delivering energy, health, ports, water, and rail services. They have combined assets of $266 billion, and their boards are intended to provide strategic direction and ensure their organisations conduct themselves in an accountable and transparent manner. The processes currently used to appoint and renew Queensland government board members are not effectively identifying the skills needed or appointing people within a reasonable time frame.

The Department of the Premier and Cabinet provides guidance to ministers and to the departments responsible for the boards. This guidance was developed 12 years ago and needs to be updated.

Boards benefit from having members with diverse qualifications and experience. While more than half of the directors on government boards are women, data is not readily available on, for example, how many members are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples or are people with disability.

In this report, we have focused on the board recruitment processes of the 4 departments that are responsible for the largest government boards. At present, several issues are making it difficult for them to ensure suitable candidates are appointed to the boards in a timely way.

The right skills and fair remuneration

Some issues relate to attracting people with the right skills. For example, departments are generally not systematically consulting their boards to identify skills gaps before recruiting. The Department of Health is the exception, having worked with its boards to develop a matrix of necessary skills. Boards are well aware of some of the skills they need – including board governance skills. At present, only one-third of directors have completed a board governance course.

The widest field of applicants is not always sought. For example, Queensland Treasury does not broadly advertise vacancies for its government owned corporation boards. This narrows the field of applicants, it can give the impression that appointees are not independent, and it is not in line with better practice as advised by the Australian Institute of Company Directors and others.

Also, there has been no change to remuneration rates for directors on government boards for 7 years, which again narrows the field of skilled applicants.

A reasonable time frame

Other issues relate to long time frames. No guidance is currently available to departments on this, and it often takes 12 months to fill board vacancies. Candidates wait an average of 6 months to find out if they have been successful, and most find out only when the outcome is publicly announced. This risks preferred candidates choosing to go elsewhere.

In some cases, vacancies on the boards of government owned corporations have gone unfilled for up to 2 years. At times, boards of statutory bodies have not had enough active members to make decisions.

Departments need to check the claims of candidates. This is an important step that must be done quickly so as not to hold up the process. While all 4 departments conduct checks, only the Department of Health confirms academic qualifications. This means there is a risk that unsuitable candidates are being appointed. Also, candidates are not currently able to check for potential conflicts of interest until they join a board, when it may be too late.

Recommendation

We recommend the Department of the Premier and Cabinet works with Queensland Treasury and relevant departments to develop an overarching framework to bring the recruitment process for boards in line with better practice. This will ensure recruitment is driven by the board, is timely, and fairly remunerates members for their contribution.

1. Conclusions

At present, departments (with the exception of the Department of Health) that are responsible for managing recruitment for Queensland government board members are not effectively working with the boards to identify the diverse set of skills needed. Long approval times and other delays are not effective in ensuring successful candidates are appointed within a reasonable time.

Ensuring those in charge of government owned entities have a clear strategic focus and manage the assets well can maximise the benefit to the community in terms of quality service and regulatory protection, and in generating returns. Boards play a major part in this, so making sure board members have the appropriate mix of skills and competencies to effectively undertake their roles is crucial.

The Department of the Premier and Cabinet (DPC) provides guidelines for the departments who manage the recruitment for boards. These guidelines are 12 years old and do not provide strong guidance to departments on the benefits of a regular, formalised skills gap analysis, of advertising positions openly, or on the importance of appointing people quickly.

Departments have different policies and practices for appointing and renewing board members across different bodies (government owned corporations, statutory bodies, and hospital and health services). Each process has its strengths and weaknesses, and each could benefit from being aligned with better practice such as that highlighted by the ASX Corporate Governance Council and the Australian Institute of Company Directors.

Of the 4 departments we focused on (because they are responsible for the boards of large government entities) only the Department of Health has been following better practice and consulting its boards to undertake a regular, formalised skills gap analysis to identify what is needed.

While the other 3 departments have informally discussed skills gaps with their boards, the boards need to be involved regularly and formally. Without first formally assessing and documenting the skills gaps, the other selection processes (searching, checking, recommending, and appointing) may not result in boards having the right people to develop and implement their strategies.

Vacancies on government owned corporation boards are not advertised broadly by Queensland Treasury. This approach relies heavily on using the networks of the department and the minister to identify preferred candidates. Not advertising broadly can give the perception that having highly qualified, experienced and diverse candidates is not the only consideration when making appointments.

Remuneration also plays a part in attracting and retaining high-quality board members. DPC has not reviewed the remuneration rates for board chairs and members for 7 years. Queensland boards should be in a position to compete for the best candidates with other entities, and uncompetitive remuneration rates reduce the pool of high-quality candidates to choose from. Members need to be appropriately and fairly compensated for the time they invest and the skills and experience they contribute.

In terms of time frames, DPC recommends departments start planning to replace (or reappoint) directors 6 months before their terms expire, but the process takes 12 months on average. Candidates wait an average of 6 months to hear the outcome of the recruitment process. Candidates for statutory boards do not receive a courtesy phone call or email before the successful candidate is publicly announced. This increases the risk that other boards will snap up good quality candidates during the wait time. Unlike New South Wales and Victoria, Queensland has no set time frames for various stages of appointment.

Vacancies on the boards of government owned corporations are going unfilled – in fact, in 2019, a quarter of the vacancies on government owned corporations were left unfilled. As a result, there is a risk that government boards may not have the required number of directors to make decisions. Leaving positions unfilled for up to 2 years also places additional pressure on the remaining board members and creates a risk that threats and opportunities may be missed as additional perspectives are not available.

While timeliness is important, it is crucial that departments complete due diligence checks on the backgrounds and claims of candidates before they seek approval/endorsement from Cabinet. Candidates also need access to information to be able to identify if any of their interests conflict with the entities’ (and their suppliers) and if any conflicts can be managed. Boards told us the best way to facilitate this was to involve the chair in the selection process.

DPC advises departments on the key checks to make, and all 4 of the departments have been undertaking suitability checks of candidates. There is however no advice on the importance of checking candidates’ academic qualifications – and only the Department of Health has been doing so. As a result, there is a risk that unsuitable people are being recommended for appointment if they are overstating or misrepresenting their academic qualifications.

The appointment of members to government boards needs to be open and quick in order to attract and retain the best and brightest people.

2. Recommendations

Whole-of-government approach

We recommend that the Department of the Premier and Cabinet:

-

collects consistent information on the diversity characteristics of all people appointed to boards to allow it to analyse the diversity of members and report publicly on how boards reflect the diversity in the broader community

-

develops, in collaboration with Queensland Treasury and relevant departments, a whole-of-government, overarching framework (aligned to better practice as outlined by the ASX Corporate Governance Council and the Australian Institute of Company Directors) for the appointment process for large boards (see Appendix D) that includes:

- requiring departments to request boards complete a formal skills matrix (including qualifications) to inform performance evaluation, succession planning and to determine the skills needed for each vacancy

- requiring departments to request board members have a performance evaluation completed prior to reappointment

- providing advice to boards on how to determine if a member’s long tenure has affected their independence

- providing advice to ministers and departments on the benefits of improving transparency and the applicant pool, by publicly advertising vacancies

- requiring checks of the academic qualifications of candidates

- involving board chairs more closely in the appointment and renewal process, to allow candidates to conduct their own due diligence and discuss potential conflicts of interest and determine if they can be successfully managed

- proposing indicative time frames for each phase of the appointment process, including for approval

- setting timeliness performance targets to evaluate the effectiveness of the appointment process

-

evaluates the effectiveness of the Queensland Register of Nominees database to readily identify people with the skills needed

-

sets fair and competitive remuneration rates for board members, commensurate with size, complexity and responsibility.

Department-led recruitment

- We recommend that departments managing the recruitment process for ministers responsible for large government boards implement the whole-of-government framework developed by the Department of the Premier and Cabinet in Recommendation 2.

Reference to comments

In accordance with s. 64 of the Auditor-General Act 2009, we provided a copy of this report to the relevant entities. In reaching our conclusions, we considered their views and represented them to the extent we deemed relevant and warranted. Any formal responses from the entities are at Appendix A.

3. The right skills

In this chapter, we report on our observations regarding the skills of board members of large Queensland government boards (those with operating results greater than $5 million or assets greater than $100 million). Appendix D lists the large entities.

We selected 4 departments that recruit for these boards across a mix of sectors – energy, health, ports, water, and rail. They are the Department of Health; the Department of Employment, Small Business and Training; the Department of Regional Development, Manufacturing and Water; and Queensland Treasury. We have also reported our findings on the steps they currently use to identify the skills boards need, and to search for potential candidates.

Members of government boards set the strategic direction for the entities they govern. To function effectively, a board needs people with skills gained through practical business or industry experience or recognised academic qualifications. Relevant qualifications for boards could include law, financial management, information technology, public relations, and infrastructure. Boards also look for industry-specific qualifications. For example, a board in the health sector typically includes members with medical qualifications, and boards in the transport sector typically include some members with engineering qualifications.

There are specific courses for directors that cover their roles and the role of the board itself, including legal responsibilities, governance principles, and financial literacy.

The Department of the Premier and Cabinet maintains a talent pool of people who have registered their interest in serving on a board – the Queensland Register of Nominees (QRON). QRON is one avenue departments may use to identify suitable candidates, but it is not the only source. It publishes limited information on the roles and functions of boards and the details of board members on the Queensland Register of Appointees (QROA).

Throughout this report, we have cited ‘better practice’, mainly from the ASX Corporate Governance Council and the Australian Institute of Company Directors (AICD). Each organisation publishes better practice guides for board governance and for the recruitment of members.

What skills and perspectives do current board members have?

Board chairs and members told us |

|

|

The board chairs and members we interviewed commented that searching for board members with the required skills is a major focus for ensuring the boards have no skill gaps, for example, by replacing an outgoing board member with someone with similar skills. Board chairs and members want better succession planning and notice when board members are not being reappointed. This would help to deliver a more rigorous and timely appointment process. All the board chairs and members we interviewed strongly advocated for diversity as a key consideration in the search for new board members. They observed that chairs are not always involved in the appointment of the new board members. This can lead to appointments that may not be the best or preferred fit for the board and the required skills. |

|

Qualifications of board members

Not all board members have higher education qualifications or have completed a specific board governance course.

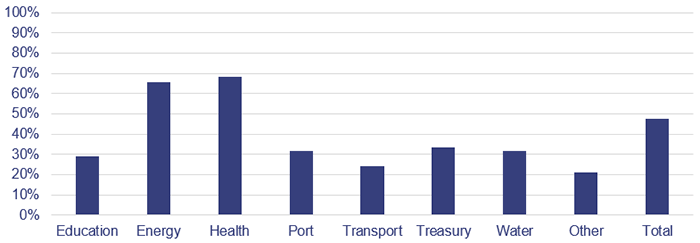

We examined the qualifications of Queensland government board members by reviewing the annual reports of the large entities, as there is no centralised information on board members’ competencies or qualifications. Members reported they hold a range of qualifications, often related to the relevant sector (for example, in engineering, information technology, or education). As shown in Figure 3A, just under half (47.2 per cent) of the current board members of large entities reported they have attained a higher education qualification.

Note: Entities publicly reported these governance qualifications in their annual reports; they have not been audited.

Queensland Audit Office, from the 2021 annual reports of large entities.

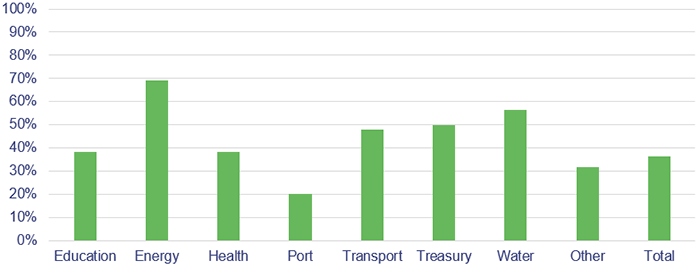

As shown in Figure 3B, just over one-third of members (36.3 per cent) reported they had completed specific courses focused on board governance, such as a directors’ course.

Note: Entities publicly reported these governance qualifications in their annual reports; they have not been audited.

Queensland Audit Office, from the 2021 annual reports of large entities.

The Department of the Premier and Cabinet collects information on skills and qualifications from nominees when they register on QRON. The Department of the Premier and Cabinet has not engaged with the boards to confirm if the listing of skills that nominees are asked to identify when they register, match the skills boards are looking for. It may not be asking people registering on QRON to nominate if they have the skills most needed. We look at other aspects of QRON in the next chapter.

How many women are on boards?

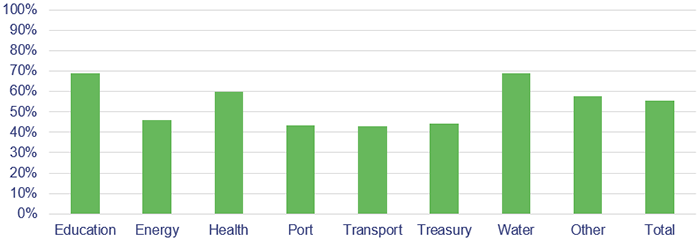

The government set a target in 2015 to achieve gender balance on most government boards. In 2021, the proportion of women on most boards was 53.7 per cent. Figure 3C shows that as of April 2021, for the large entities within scope of this audit, 55.4 per cent of board members were women, with some variation across the sectors.

Queensland Audit Office, from the Department of the Premier and Cabinet’s Queensland Register of Appointees.

How diverse are boards in other ways?

While the Department of the Premier and Cabinet collects data and reports on the proportion of women on government boards and bodies, it does not collect it on other aspects of diversity. For example, it does not know how many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, or people with disability are on the boards. Without understanding the current levels of diversity, the Department of the Premier and Cabinet does not know that board representations are a reflection of the diversity in the broader community.

While departments collect information from successful candidates appointed to boards, the Department of the Premier and Cabinet does not bring together the data from the departments and QRON, so it cannot analyse the full range of diversity characteristics of boards.

Better practice tells us

The Australian Institute of Company Directors (AICD) recognises that a contemporary board needs diversity in terms of gender, age, and culture. It also points out that directors should be chosen on merit, through a transparent process, and in alignment with the board’s purpose and strategy.

Recommendation 1 |

|

We recommend that the Department of the Premier and Cabinet collects consistent information on the diversity characteristics of all people appointed to boards to allow it to analyse the diversity of members and report publicly on how boards reflect the diversity in the broader community. |

Do departments work with the board to identify the skills and experience needed before they search?

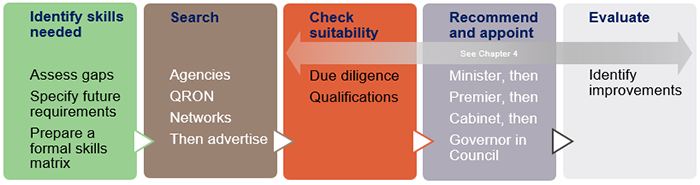

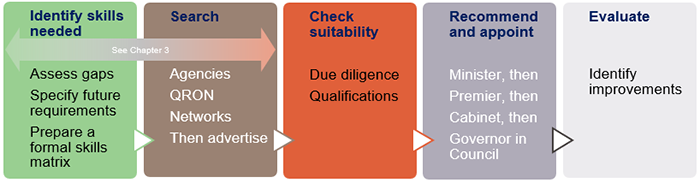

We assessed the basic approaches followed by the 4 departments for board recruitment. They each have their own processes and procedures, but we identified some common steps, as outlined in Figure 3D.

This section covers the first 2 steps in the recruitment process. Our findings on the last 3 steps are covered in Chapter 4. See Appendix C for an assessment of each department’s process compared to better practice.

The government establishes individual statutory bodies and government owned corporations under specific legislation, which may include requirements about the composition of the board. For example, hospital and health boards need members with medical backgrounds and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Note: Due diligence checks are designed to reduce the risk of an unsuitable person being appointed. They include checks of the bankruptcy and disqualified directors’ databases. They also include a criminal history police check. They are completed for candidates shortlisted by the minister.

Queensland Audit Office, from documents of the Department of Health; Department of Employment, Small Business and Training; Department of Regional Development, Manufacturing and Water; and Queensland Treasury.

Step 1 – Identify the skills and experience needed |

Boards need to formally identify the skills and experience they need so the departments can find them the best people. Departments need to work with the boards to identify the skills of any board member whose term is expiring. Also if members seeking reappointment are performing well, and if the board needs new skills to address emerging risks or changes in strategy – for example, with regards to cyber security. Currently, the departments informally discuss with the chair what skills they need and there is no requirement for board members seeking reappointment to undertake a performance assessment.

Skills matrix

The Department of Health uses an agreed list of required skills (a skills matrix) to assess all hospital and health board members. It uses the assessment results to identify gaps in the boards’ skills, to provide information to selection panels and to develop selection criteria. The matrix is completed with input from the chairs and is formally documented.

In 2020, the Department of Employment, Small Business and Training developed a skills matrix in consultation with a recruitment consulting firm.

The other departments do not use a formal assessment for statutory bodies, but they do informally discuss the desired skills with the chair and/or the minister.

Queensland Treasury’s Guide for Board Appointments to Government Owned Corporations, Queensland Rail and Seqwater (February 2019) specifies that, for each vacancy, a list of potential nominees and a board skills matrix should be prepared and provided to the relevant ministers.

Queensland Treasury informally consults with the chair of the board, the department, and the minister on the skills needed, and it maintains a list of existing board members and potential skills gaps for the recruitment process. However, it does not complete a formal skills matrix with documented input from the chair. (Appendix E contains an example of a skills matrix for directors.)

Government boards in New South Wales and Victoria must use a skills matrix in the appointment process.

Better practice tells us

The ASX Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations (4th Edition, 2019) recommends companies listed on the Australian Securities Exchange should have (and disclose to its shareholders) a board skills matrix setting out the mix of skills the board currently has or is looking to achieve in its membership.

A skills matrix can help the board identify any gaps in its collective skills that it should address through professional development or by taking on new directors.

The board should regularly review its skills matrix to make sure it covers the skills needed to address existing and emerging business and governance issues relevant to the entity.

Once a skills matrix has been completed, to assist in formalising the requirements of the different governance roles, a position description may be compiled for the chair and each director, and then reviewed and adjusted regularly. These position descriptions can stress the specific roles each director is expected to bring to the board in line with their identified competencies.

While these principles were developed to guide ASX-listed companies, they are better practice and are relevant to government boards.

The Governance Institute of Australia advises boards that when creating the skills matrix, they should consider reviewing and assessing the competencies of board members, either following completion of a questionnaire by each director or as part of an overall collaborative approach to assessing board skills.

Performance evaluation prior to reappointment

In Queensland, there is no formal requirement for board members to undertake a performance review prior to reappointment. In fact, the Department of the Premier and Cabinet’s guidance does not require boards of statutory bodies to regularly undertake any individual or collective performance evaluations.

Queensland Treasury’s guide recommends that boards of government owned corporations conduct individual and collective performance evaluations regularly – at least every 2 years. The boards should provide a written report to the relevant ministers on the results of the evaluation. Overall, they report in their annual reports that they undertake the required evaluations.

There is no requirement for the departments or ministers to consider the performance evaluations of a board member prior to reappointment, and Queensland Treasury does not access the evaluation reports to determine where gaps in skills might be.

The Victorian Government requires each board member to undertake a performance review prior to reappointment. The relevant department completes the review in consultation with the board.

Better practice tells us

The ASX Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations (4th Edition, 2019) recommends that:

- entities have (and disclose to its shareholders) a process for periodically evaluating the performance of the board, its committees, and individual directors

- boards disclose whether they have undertaken a performance evaluation for each reporting period, in accordance with their defined process.

The board performs a pivotal role in the governance framework of an entity. It is essential that it has in place a proper process for regularly (preferably annually) reviewing the performance of the board, its committees, and individual directors. Boards should pay particular attention to addressing issues that may emerge from that review, such as the currency of a director’s knowledge and skills, or if other commitments are affecting a director’s performance.

While these principles were developed to guide ASX-listed companies, they are better practice and are relevant to government boards.

Recommendation 2(a)(b) |

|

We recommend that the Department of the Premier and Cabinet develops, in collaboration with Queensland Treasury and relevant departments, a whole-of-government, overarching framework (aligned to better practice as outlined by the ASX Corporate Governance Council and the Australian Institute of Company Directors) for the appointment process for large boards (see Appendix D) that includes:

|

Tenure

There is no guidance to departments on how to consider the optimum tenure length for board members. Members with more than 10 years on a board may be seen as too familiar with an entity’s management, (known as ‘reduced independence’), but members with little time on the board may not understand the entity’s process, systems, and people. Departments need to bring in new members to renew the board with fresh ideas and perspectives and allow them to gain experience and develop a good understanding of the entity.

We analysed the tenure of current board members and found that Queensland government boards have a mix of members with experience and fresh perspectives. There are no current members of boards with more than 10 consecutive years of appointment to a single board.

Better practice tells us

The ASX Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations (4th Edition, 2019) recommends that boards annually assess the independence of each member. It identifies several factors for boards to include in the assessment, including tenure.

The mere fact that a director has served on a board for a substantial period does not mean they have become too close to management or a shareholder to be independent. However, the board should regularly assess whether that might be the case for any director who has served in that position for more than 10 years.

While these principles were developed to guide ASX-listed companies, they are better practice and are relevant to government boards.

Recommendation 2(c) |

|

We recommend that the Department of the Premier and Cabinet develops, in collaboration with Queensland Treasury and relevant departments, a whole-of-government, overarching framework (aligned to better practice as outlined by the ASX Corporate Governance Council and the Australian Institute of Company Directors) for the appointment process for large boards (see Appendix D) that includes:

|

Step 2 – Search for people with the right skills and experience |

Departments must search for potential candidates on the Department of the Premier and Cabinet’s Queensland Register of Nominees (QRON). They can also use national/international advertising campaigns. Some departments use a specialist recruitment agency to assist with the search. They may also use the existing networks of the board, department, or minister.

Queensland Register of Nominees

At the start of our audit, departments did not have direct access to perform QRON searches for potential candidates. They completed a search form, listing the wanted skills, then submitted the form to the Department of the Premier and Cabinet which ran the search and sent them the results. Departments told us the search functionality in QRON could be better targeted to identify key characteristics they were looking for, such as individuals’ previous experience on government boards.

The Department of the Premier and Cabinet has recently made changes to allow departments to search directly for candidates within QRON. It has not asked departments if the changes are meeting their needs in finding candidates for boards, so it is not clear if it has resolved the issues raised by departments.

The Department of the Premier and Cabinet encourages all agencies to use the Join a Board website to advertise board vacancies.

Data on the success rate of candidates from QRON is not broadly available. Queensland Health advised us that, of the 138 current members (as of June 2021) of hospital and health boards, it had identified 3 successful candidates (2.2 per cent) through QRON.

Recommendation 3 |

|

We recommend that the Department of the Premier and Cabinet evaluates the effectiveness of the Queensland Register of Nominees database to readily identify people with the skills needed. |

Public advertising of vacancies

Generally, there is no legislative requirement for departments to openly advertise for board members. The Hospital and Health Boards Act 2011 requires the minister to advertise board positions, but most other legislation for statutory bodies and government owned corporations does not specify the process used to fill board vacancies.

The Department of Health; Department of Employment, Small Business and Training; and the Department of Regional Development, Manufacturing and Water have publicly advertised vacancies on their boards, formed selection panels, and developed selection criteria clearly listing the skills they are seeking, even though they were not legislatively required to do so.

Queensland Treasury has not developed selection criteria, formed selection panels, or advertised vacancies to fill board positions for government owned corporations. It has used QRON, internal networks, and recommendations from chairs or the minister to search for suitable candidates. In 2021, it published an expression of interest on the Department of the Premier and Cabinet's Join a Board website. As a result, it may be missing opportunities to identify a broader range of potential candidates to fill board roles.

A lack of openness about how government identifies and appoints board members can create a perception that it is making appointments for reasons other than securing highly qualified, experienced, and diverse candidates. This can be a disincentive for prospective candidates, as they may not wish to invest their time and effort in a process perceived as unfair.

The New South Wales and Victorian governments both require departments to:

- publicly advertise vacancies

- develop selection criteria

- use panels to assess candidates.

Better practice tells us

The ASX Corporate Governance Council recommends that entities have a formal, rigorous, and transparent process for the appointment and reappointment of directors. This includes preparing a description of the role and capabilities required for a particular appointment.

While these principles were developed to guide ASX-listed companies, they are better practice and are relevant to government boards.

The AICD advises that, while in the past boards have typically relied on their informal networks to find suitable candidates to fill board positions, the demand for accountability is now making the selection of directors more open and transparent. Boards can no longer rely on personal networks and retiring senior executives from their own industry to provide the range of skills and experience they need.

The AICD also cautions boards to ensure they are not filled with ‘mates’. A key feature of an effective board is independence of mind. A board full of directors who always agree with each other will not function efficiently. The board must include people who fill a defined need, challenge the status quo, ask appropriate questions, and are persistent in getting answers. Governance reviews have identified that relying on the contacts of existing directors is a major reason for the historic lack of diversity of many boards.

Recommendation 2(d) |

|

We recommend that the Department of the Premier and Cabinet develops, in collaboration with Queensland Treasury and relevant departments, a whole-of-government, overarching framework (aligned to better practice as outlined by the ASX Corporate Governance Council and the Australian Institute of Company Directors) for the appointment process for large boards (see Appendix D) that includes:

|

Fair and competitive remuneration rates

The Department of the Premier and Cabinet centrally sets the remuneration rates for board chairs and members. The rates have remained the same for 7 years.

The Remuneration Procedures for Part-Time Chairs and Members of Queensland Government Bodies clearly articulates that there is an element of community service in participating on government boards. The rates are based on the revenue, assets, and complexity of an individual government owned corporation or statutory body. Departments can apply to Cabinet for exemptions to the rates when setting up a new government owned corporation or statutory body, or when appointing new members.

The Department of the Premier and Cabinet issued the current remuneration rates for government bodies in 2014 and has not reviewed them since. Over this period, real wages for the public sector have grown by 7.1 per cent, and the wage price index (similar to the consumer price index) has grown by 17.5 per cent. Victoria updated its board remuneration rates in July 2021, and New South Wales in April 2021.

In 2021, the fees for Queensland chairs ranged from $7,000 to $227,000 and directors' fees ranged from an estimated $3,600 to $92,000 per year. See Appendix F for a full listing of the rates and the range for board chairs and members.

Queensland government boards compete for members with interstate government boards and the private and not-for-profit sectors. Out-of-date remuneration rates are a barrier to attracting and retaining the best quality board members.

Better practice tells us

The ASX Corporate Governance Council recommends that entities pay enough remuneration to attract and retain high-quality directors.

The council advises that remuneration is a key driver of culture. When setting the level and composition of remuneration, a listed entity needs to balance its desire to attract and retain high-quality directors with:

- the implications for its reputation and standing if the community perceives it pays excessive remuneration to directors and senior executives

- its commercial interest in controlling expenses.

While these principles were developed to guide ASX-listed companies, they are better practice and are relevant to government boards.

Recommendation 4 |

|

We recommend that the Department of the Premier and Cabinet sets fair and competitive remuneration rates for board members, commensurate with size, complexity and responsibility. |

4. Reasonable time frames

There is competition for good board directors, and an appointment process that is seen as slow may be a disincentive to potential candidates. Completing each step within a reasonable time ensures boards do not lose quality candidates to other (interstate, private, or not-for-profit) boards. It is also important for departments to continuously improve these processes.

This chapter reports our findings on the timeliness of the recruitment steps the 4 departments we focused on (the Department of Health; the Department of Employment, Small Business and Training; the Department of Regional Development, Manufacturing and Water; and Queensland Treasury) use to check suitability of candidates, and the steps for recommending appointments. We have also examined how they evaluate their processes.

The departments undertake the process on behalf of, and in conjunction with, the relevant minister’s office. Departments have no approving authority for appointments. Instead, ministers are responsible for recommending board appointments for government owned corporations and statutory bodies to the Governor in Council (Governor in Council is the Governor acting on the advice of Executive Council, which in practice is the Governor and at least 2 ministers (executive councillors).

Reasonable and competitive time frames for appointment

Board chairs and members told us |

|

|

Board chairs and members acknowledge the process is lengthy and, in some cases, has caused a level of frustration for boards and candidates. They also commented that the delays in the appointment process create a reputational risk for the chair when they have recommended someone who waits a long time to be advised of the outcome of the process. The board chairs and members we interviewed supported having a target time frame for approvals of appointments. |

|

There is no guidance for departments and approvers on indicative time frames for each stage of the process. Some board members are waiting up to 7 months to find out if they are successful. Reappointments can take even longer.

The Department of the Premier and Cabinet’s guidance on significant appointments is contained in The Queensland Cabinet Handbook, and advises ministers and departments to start recruitment or reappointment at least 6 months prior to Cabinet consideration. This is to ensure adequate time for consultation obligations and scheduling of submissions to Cabinet.

The process to appoint public servants does not apply to government boards, but the Public Service Commission advises departments on the recruitment process for public servants:

- selection decisions and the notification of outcomes must take place in a timely manner

- they should form selection panels and determine selection strategies prior to (or concurrent with) advertising

- vacancy advertisements will lapse if they do not make an appointment within 6 months of the closing date of the vacancy.

Applying the same rigour and courtesy to selections for board positions could improve the pool of applicants.

The impact of long recruitment time frames on the board

Boards need enough members present for decisions made at their meetings to be valid. At times, some board members have not been replaced if they resigned or when their term expired. This has meant the boards have not had the full complement of members – in some cases for 2 years.

There is a risk that if one of the remaining members were to resign suddenly or be temporarily unavailable, the board could be left unable to make decisions about such things as endorsing and signing financial statements within the statutory time frames.

Figure 4A shows how many vacancies were left unfilled on the boards of government owned corporations from 2018 to 2021.

| Vacancies | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filled | 32 | 24 | 26 | 26 |

| Not filled | 3 | 8 | 3 | 1 |

| Percentage unfilled | 8.6 | 25.0 | 10.3 | 3.7 |

Queensland Treasury board summary reports.

In fact, some entities have already not had the full complement of members. In some cases, boards of statutory bodies did not have enough active members to make decisions on occasions. Examples of boards with restricted abilities to make decisions are:

- Queensland Treasury Corporation (QTC) – in 2020 for a period of 2 weeks there were a number of vacancies on the board. Under QTC’s structure there are no quorum risks, as it is operating with a delegation function by the Under Treasurer. QTC still had 3 independent members on the board. Given QTC’s significant role in managing the state finances, not having a full complement of board members even for a short period is less than ideal.

- Gladstone Area Water Board – from 2019 to 2020 it had low attendance at meetings and could not form a quorum at times. In August 2019, the chair and one director of the board were replaced, and one further director was appointed. The board then sought an extension to sign its financial statements as the recently appointed members needed more time to become familiar with the entity’s operations.

- hospital and health boards – in 2021, delays to the appointment of 17 board members (including 3 chairs), left 10 boards without their full complement for 24 days. All but 2 of the boards were still able to function and make decisions as the deputy chairs were able to take on the chairs’ role.

Guidance to departments is out of date and not focused on achieving reasonable time frames

The guidance to departments regarding recruiting for statutory boards is 12 years old, while the guidance for government owned corporations is relatively current (2019). Neither aligns with better practice nor focuses on achieving reasonable time frames.

We audited the guidance the Department of the Premier and Cabinet provides to ministers and departments on how to manage the recruitment process and make appointments within a reasonable time frame.

We did not audit how the Department of the Premier and Cabinet manages the recruitment of board members for its relevant entities. Nor did we audit the boards themselves or the merits of the appointment of individual board members.

Department of the Premier and Cabinet – whole-of-government guidance for statutory boards

As stated previously, the Department of the Premier and Cabinet has not updated its whole-of-government guidance for 12 years. The guidance does not align with contemporary better practice. (Opportunities to do so are detailed in the following sections of this chapter.)

The department first published its guidance document – Welcome Aboard: A Guide for Members of Queensland Government Boards, Committees and Statutory Authorities – in 1998 and republished it in July 2010. The department also provides specific guidance to departments on what to include in submissions to Cabinet for the approval of members of government boards via The Queensland Cabinet Handbook.

The Department of the Premier and Cabinet advised it has reviewed the Welcome Aboard Guide, but the guide is not yet finalised as it is awaiting the outcomes of this audit.

Queensland Treasury guidance for government owned corporations

In 2019, Queensland Treasury developed a guide for board appointments to government owned corporations, Queensland Rail, and Seqwater. It was developed in response to a Crime and Corruption Commission recommendation to the Treasurer to implement a formalised policy and procedure to apply equally to all candidates for boards of Queensland government owned corporations.

This aligns to some of the elements of better practice. However, there is no guidance on the importance of ensuring appointments are made within a reasonable time frame or on the risk to the board of leaving positions unfilled.

Victoria has a single whole-of-government framework and tools to provide guidance to departments managing the recruitment process for their ministers. The framework is current (2020) and aligned with better practice principles.

Recommendation 2 |

|

We recommend that the Department of the Premier and Cabinet develops, in collaboration with Queensland Treasury and relevant departments, a whole-of-government, overarching framework (aligned to better practice as outlined by the ASX Corporate Governance Council and the Australian Institute of Company Directors) for the appointment process for large boards (see Appendix D). |

Do departments check the suitability of candidates and how are they appointed?

We assessed the basic approaches followed by the 4 departments for board recruitment. They each have their own processes and procedures for recruiting board members, but we identified common steps, as outlined in Figure 4B. This chapter covers our findings on the final 3 steps in the recruitment process. See Chapter 3 for our findings on steps 1 and 2.

Note: Due diligence checks are designed to reduce the risk of an unsuitable person being appointed. They include checks of the bankruptcy and disqualified directors’ databases. They also include a criminal history police check. They are completed for candidates shortlisted by the minister.

Queensland Audit Office, from documents of the Department of Health; Department of Employment, Small Business and Training; Department of Regional Development, Manufacturing and Water; and Queensland Treasury.

Appendix C contains an assessment of each department’s process compared with better practice.

Step 3 – Check the suitability of candidates |

Departments need to conduct appropriate checks to ensure the claims candidates make in their applications are accurate. This is an important step, but it has to be done quickly so as to not unduly delay the recruitment process.

Departments also need to check for potential conflicts of interest to determine if they can be managed. A potential conflict of interest arises when an individual’s personal interests – family, friendships, financial issues, or social factors – could compromise their judgement, decisions, or actions on a board.

Suitability checks

The 4 departments we reviewed all check criminal history, bankruptcy, and disqualified directors’ databases. Departments have been undertaking these checks after they brief the minister on the shortlist of preferred applicants. Departments have well established processes to complete most of these checks, and they do not contribute to delays.

However, the Department of Health is the only department that has been checking academic qualifications. This means there is a risk that the other departments may not identify candidates who overstate or exaggerate their qualifications, and they could appoint unsuitable people to boards.

We did not check the qualifications of board members or identify any members misrepresenting their qualifications.

Better practice tells us

The ASX Corporate Governance Council recommends that entities undertake appropriate checks before appointing a director. These should usually include checks about the person’s character, experience, education, criminal record, and bankruptcy history.

The Australian Institute of Company Directors (AICD) also advises boards that, given the legal responsibilities directors face and the collegial nature of an effectively functioning board, directors must trust and respect each other. Therefore, it is advisable that boards substantiate information candidates provide about themselves.

While these principles were developed to guide ASX-listed companies, they are better practice and are relevant to government boards.

Recommendation 2(e) |

|

We recommend that the Department of the Premier and Cabinet develops, in collaboration with Queensland Treasury and relevant departments, a whole-of-government, overarching framework (aligned to better practice as outlined by the ASX Corporate Governance Council and the Australian Institute of Company Directors) for the appointment process for large boards (see Appendix D) that includes:

|

Declaring interests and potential conflicts

Departments and candidates both have a role in identifying potential conflicts. Currently, candidates may not have access to all the information they need to identify if their interests will present conflicts and/or potential conflicts prior to accepting their appointment to the board.

Departments

All 4 departments check if potential conflicts will affect the candidate’s suitability. To do this, they ask candidates to declare their interests (current or past employment, other directorships, family relationships, partnerships, business interests, significant assets (shares), or liabilities).

The current process is designed for departments and the approvers (the relevant minister, the Premier, and Cabinet) to consider the interests so they can determine if they could compromise an individual’s judgement, decision, or actions.

The process relies heavily on the candidates themselves identifying if they have any interests that may conflict with those of the board. It requires them to know the entity’s interests in enough detail to do so.

A potential conflict does not automatically exclude a candidate, but the board needs to decide prior to appointment if it can manage the conflict.

Candidates

Candidates need to satisfy themselves that any interests they have would not constitute a conflict. Some interests are straightforward, and they would be able to identify them. For example, being on the board of a competing entity or company would be an actual conflict of interest. However, some candidates may not have access to information on the entity’s suppliers or competitors. For example, with:

- suppliers – being on the board of, or having shares in, a company with significant contracts with the entity would be a potential conflict of interest

- competitors – being on the board of, or having shares in, a company that is a competitor of a company with significant contracts with the entity would be a potential conflict of interest.

The process for appointing new directors does not include an opportunity for candidates to ask questions about their interests or discuss with the chair how they may or may not manage their conflicts. This means they cannot conduct their own due diligence over the entity and identify any potential conflicts prior to accepting the role.

This creates a risk that some conflicts may not become apparent until after new directors attend some board meetings and gain a greater understanding of the entity's business. If the board determines it cannot manage their conflicts, they may have to step down, creating an unnecessary vacancy and a need for more recruitment.

Better practice tells us

AICD advises that conflicts of interest occur when a person is in a position to be influenced, or appear to be influenced, by their private interests – or other interests – when doing their job. It could be something as simple as recommending a family member to fill a vacant position, recommending a supply contract to a friend’s business, or voting as a director for a course of action that will benefit another company in which the person has an investment.

A director has a duty to recognise conflicts of interest, but also has a duty to the organisation to bring their skills and capacities to bear to serve the entity/company. A director who must ‘leave the room’ due to their conflicts so often that they are not able to fulfil their duty may need to consider stepping down completely.

Recommendation 2(f) |

|

We recommend that the Department of the Premier and Cabinet develops, in collaboration with Queensland Treasury and relevant departments, a whole-of-government, overarching framework (aligned to better practice as outlined by the ASX Corporate Governance Council and the Australian Institute of Company Directors) for the appointment process for large boards (see Appendix D) that includes:

|

Step 4 – Recommend and approve |

Departments develop submissions to seek approval from multiple people for the preferred candidate. They require approval and endorsement by the relevant minister/s, the Premier, Cabinet, and Governor in Council.

New South Wales suggests ministers and Cabinet complete their approval of appointments in 10 working days. Victoria also sets clear time frames for the different stages of the process, giving the minister 2 weeks to consider the recommended applicants.

We analysed the time departments have taken to complete the appointment process, from when they start planning to when the names of the successful candidates are publicly announced. We also analysed how long candidates have waited for confirmation of appointment. Figure 4C lists (for the relevant years) how long the process has taken and how long candidates have waited.

| Department |

Duration of appointment process (months) |

How long candidates have waited for confirmation of approval of appointment (months) |

|---|---|---|

| Department of Health (2021) | 11 | 6 |

| Department of Regional Development, Manufacturing and Water (2021)* | 15 | 5 |

| Department of Employment, Small Business and Training (2020) | 14 | 7 |

| Queensland Treasury (2021) | 8 | Unable to calculate; data not provided |

| Average | 12 | 6 |

Note: *The long time frames for the Department of Regional Development, Manufacturing and Water are in part due to tenure of members of the Gladstone Area Water Board and the Mount Isa Water Board being extended until they are replaced, which reduces the urgency.

Queensland Audit Office, from the 4 departments’ project plans and reports.

The Department of Health formally writes to candidates not shortlisted for interview and communicates with shortlisted candidates on the progress of the process. The Department of Regional Development, Manufacturing and Water advises candidates not shortlisted that their application is not progressing further. But at present, no one advises candidates (successful or unsuccessful) prior to the official announcement.

Recommendation 2(g) |

|

We recommend that the Department of the Premier and Cabinet develops, in collaboration with Queensland Treasury and relevant departments, a whole-of-government, overarching framework (aligned to better practice as outlined by the ASX Corporate Governance Council and the Australian Institute of Company Directors) for the appointment process for large boards (see Appendix D) that includes:

|

Do departments evaluate the recruitment process? |

Evaluation provides an opportunity for departments to consider how effectively and efficiently they have managed an appointment and reappointment process, and if things could be done better and faster next time.

Of the 4 departments we audited, only the Department of Health regularly evaluates the effectiveness of its appointment process.

It developed a formal project plan outlining the steps and milestones to fill all vacancies on hospital and health boards. This included an evaluation at the end of the process to identify process improvements. The department conducted the evaluation itself and identified several issues with the process and timing.

Victoria’s Public Service Commission advises that systematically collecting data can help with the evaluation of a range of practices and help to improve practices. It suggests collecting the following information on the appointment process:

- time taken to fill the vacancy

- selection ratio (the ratio of candidates to vacant positions)

- number of positions refused

- number of unfilled vacancies.

Recommendation 2(h) |

|

We recommend that the Department of the Premier and Cabinet develops, in collaboration with Queensland Treasury and relevant departments, a whole-of-government, overarching framework (aligned to better practice as outlined by the ASX Corporate Governance Council and the Australian Institute of Company Directors) for the appointment process for large boards (see Appendix D) that includes:

|