Overview

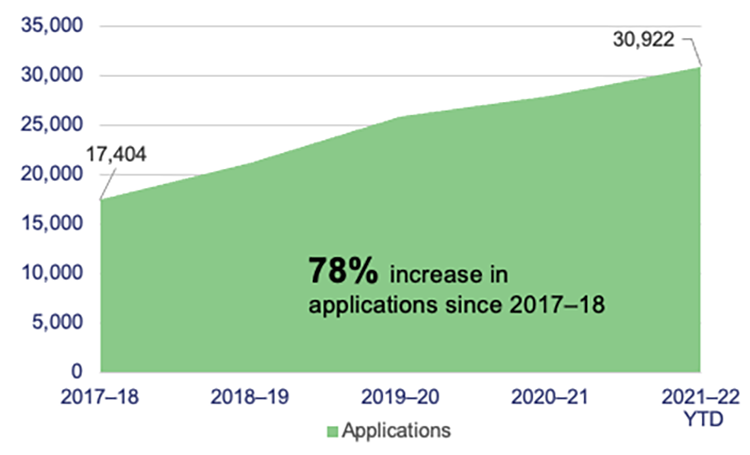

The government funds social housing to help Queenslanders with the greatest housing need. Over the last 4 years, the number of approved applicants on the housing register has grown by 78 per cent. As many social and economic factors, including inflation and rising interest rates, contribute to growing housing pressures, the government needs to take a multi-faceted approach to the demand for social housing.

Tabled 12 July 2022.

Report on a page

Social housing is rental housing that is funded, or partly funded, by the government. It is available to eligible Queenslanders who cannot access or sustain a tenancy in the private rental market. This audit examines whether social housing is effectively managed by the Department of Communities, Housing and Digital Economy (the department) to meet the needs of vulnerable Queenslanders.

Managing social housing applications

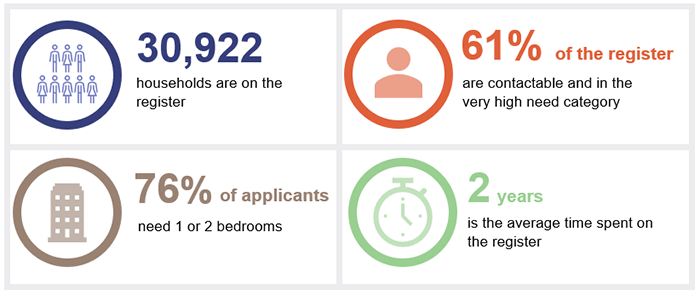

The department assesses a household’s eligibility and need for social housing based on established criteria. The housing register (the register) is a central list of all applicants approved for social housing. It has grown by 78 per cent over the last 4 years. In March 2022, there were 30,922 households on the register. The department does not forecast how the register will grow in coming years.

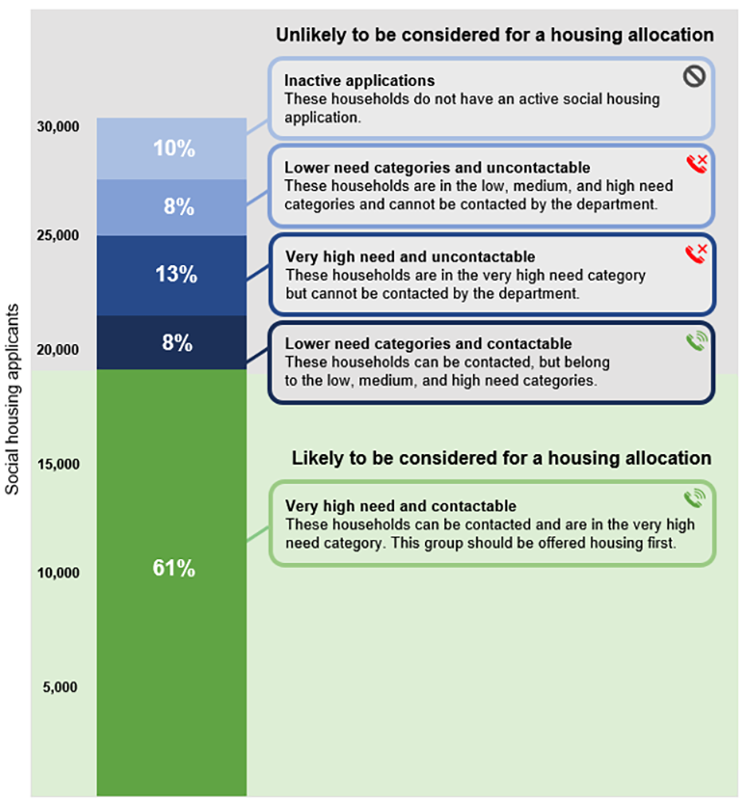

Social housing applicants are assigned to a need category on the register. The need categories are low, moderate, high, and very high. Around 61 per cent of the households on the register are classified as having very high need and are able to be contacted by the department. These are the only applicants likely to be allocated housing. Since 2019, the department has classified all new applicants as very high need. The department has not clearly communicated this to the existing households on the register and other stakeholders.

The remaining 39 per cent of applicants are in lower need groups, cannot be contacted or have inactive applications. These should be reviewed and removed from the register if they are no longer eligible.

QAO analysis of data from the Department of Communities, Housing and Digital Economy.

Some applicants on the register have circumstances that require urgent social housing. Each housing service centre prioritises these applicants for allocation using separate local lists. There is no central process to identify and monitor applicants for priority allocation.

The department’s assessment and allocation processes have not been consistently applied. We found examples where needs were not recorded correctly in applications or eligibility was not confirmed before making a housing allocation. Some assessments and allocations were missing requisite internal checks.

Optimising housing outcomes

Around 15 per cent of government-managed social housing is under occupied. Tenants are not required to relocate to smaller dwellings if their needs have changed since the start of their tenancy. The department also lacks a formal process to proactively identify tenants that it can support to transition away from social housing and into the private rental market.

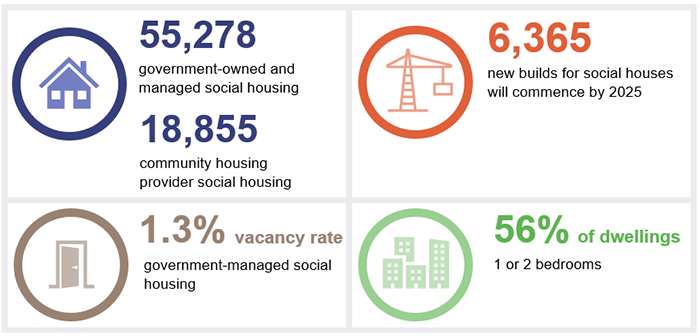

In March 2022, there were 74,133 social housing dwellings in Queensland. The department intends to commence building another 6,365 dwellings by 2025. While the style and location of new builds aligns with current social housing demand, these dwellings alone will not be sufficient as growth of the register is likely to accelerate with rising interest rates and a tightening rental market.

We made 8 recommendations to improve the department’s management of the register and application process, its housing allocation procedures, and its approach to managing housing allocations over time.

1. Audit conclusions

The department’s current processes to manage the housing register are not effective. The department needs to take a multi‑faceted approach to the growing housing pressure. It needs to improve its current systems and processes to better manage the increasing demand for social housing in Queensland.

Assessing and reviewing housing need

The department’s process to assess housing need is focused on an individual’s circumstances, however its approach has not been communicated effectively. Public information refers to need categories no longer used by the department. Since 2019, the department has classified all new applicants as very high need.

Prior to 2019, social housing applicants could also be assigned to low, moderate, and high need categories. Many applicants on the register are still in these categories and are unlikely to be allocated housing. Many social housing applicants have also been deemed uncontactable by the department or have inactive applications. These applicants are unlikely to be allocated housing and should not appear on the register.

The department’s need assessments are not recorded consistently. Around one in 5 applications we examined did not correctly record an applicant’s needs. Around half were also missing an internal check before approval.

The department does not forecast future social housing need in Queensland or what the register will look like in the next 3 years. For example, it does not model how changes in the cost of living and rising rents might impact the demand for social housing. This information is necessary to better inform its response to housing needs.

To manage the register effectively, as a matter of priority the department needs to improve its policies, procedures, and information systems. This should include identifying and evaluating other types of housing assistance offered by the department.

Allocating social housing

The department’s process to allocate social housing is not consistently applied. Around one in 5 allocations we examined did not record a pre-allocation check – this is an important requisite internal step to confirm an applicant’s needs have not changed.

The department’s 17 housing service centres maintain separate lists of applicants in their area who need a priority housing allocation. There are no standard criteria for a priority allocation and the department does not have visibility over each housing service centre’s list, thereby creating a risk of the inconsistent treatment of applicants.

Around 8,430 social housing dwellings have 2 or more spare bedrooms. The department does not require tenants to relocate to smaller housing that better aligns with their needs. The department advised it works with tenants to encourage them to move, where appropriate. The department also has no structured process to proactively identify social housing tenants who could transition to private rentals or home ownership with the right support. This could free housing for applicants on the register.

Building more social housing

The department has planned new social housing in areas with current high need. The 6,365 builds planned to commence by 2025 will help to increase social housing supply, however it will not be enough to keep up with increasing demand.

2. Recommendations

We have directed the recommendations in this report to the Department of Communities, Housing and Digital Economy (the department).

Applying for social housing

We recommend the department:

- clearly communicates the needs assessment process it applies. This should include a proactive campaign to key stakeholders and consistent and complete information on the department’s website (Chapter 4)

- periodically confirms the ongoing eligibility of all social housing applicants and updates the register as needed. Applicants who the department determines are uncontactable, or have inactive applications, should not appear on the register (Chapter 4)

- consistently completes and reviews all new housing applications (Chapter 4)

- models future demand for social housing at the state and regional levels, incorporating historical and predictive analysis that includes social, economic, and environmental factors to inform its planning, investment, and service delivery. (Chapter 4)

Social housing allocations

We recommend the department:

- consistently performs pre-allocation checks through a systems-based process (Chapter 5)

- implements a consistent process to identify, approve, record, and monitor applicants on the register for priority allocations across the state (Chapter 5)

- reviews its approach to tenancy management to better respond to the changing needs of tenants in social housing (Chapter 5)

- uses structured conversations to identify and support tenants who can transition away from social housing. (Chapter 5)

Reference to comments

In accordance with s. 64 of the Auditor-General Act 2009, we provided a copy of this report to relevant entities. In reaching our conclusions, we considered their views and represented them to the extent we deemed relevant and warranted. Any formal responses from the entities are at Appendix A.

3. Social housing in Queensland

The Department of Communities, Housing and Digital Economy is responsible for social housing in Queensland. It offers a range of products and services to help Queenslanders who need housing assistance. Social housing is intended to help Queenslanders with the greatest housing need.

Social housing is rental housing that is funded or partly funded by the government. It is available to Queenslanders who meet the eligibility requirements and cannot access or sustain a tenancy in the private rental market.

Social housing includes public housing, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander housing, and housing owned or managed by community housing providers in partnership with the Queensland Government (community housing).

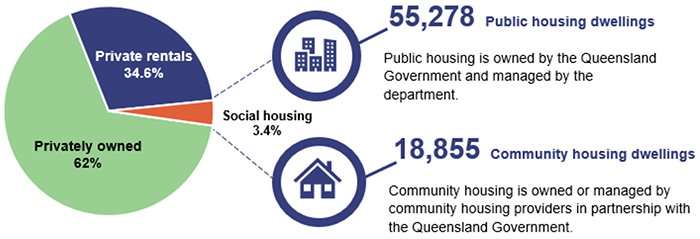

Around 3.4 per cent of dwellings in Queensland are social housing

Figure 3A shows Queensland’s housing profile in June 2020 and outlines the composition of social housing in the state in March 2022.

Audit focus

The objective of this audit was to examine whether social housing is effectively managed to meet the housing needs of vulnerable Queenslanders. We focused on key aspects of the department’s processes, including how it manages assessments, applications, and allocations for social housing. We also assessed if Queensland’s planned social housing investments align with current social housing need.

We did not examine tenancy management (including rent setting or collection), tenant behaviour, or property maintenance. We also did not assess how community housing providers, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander housing providers, manage tenancies in their housing. Figure 3B provides an overview of our audit scope.

QAO information.

4. Applying for social housing

This chapter examines how the Department of Communities, Housing and Digital Economy manages social housing applications. This includes assessing applicants’ eligibility and housing needs, managing the housing register, and forecasting future demand.

Social housing needs assessments

To be eligible for social housing in Queensland, applicants must:

- meet citizenship and residency requirements

- meet income, asset, and property ownership requirements

- need to move because their current housing is unsuitable.

Applicants must also be experiencing a combination of financial and non-financial barriers to accessing secure housing. This could include multiple periods of unemployment, permanent and significant disability, or a history of homelessness. The department refers to these as wellbeing indicators.

Since 2019, an applicant can only join the register if they have at least 2 complex non-financial indicators and at least one financial indicator (outlined in Appendix C). Prior to 2019, applicants could join the register if they had only one wellbeing indicator (then called appropriateness criteria). This approach was updated to better align social housing with very high need applicants.

The department uses pathway planning to identify needs

The department uses pathway planning to tailor housing solutions to each applicant’s situation and needs.

Pathway planning involves a detailed conversation with housing customers to understand their circumstances. This could include information about their home, money, safety, health and social connections.

The department conducts a pathway planning conversation with applicants, then assesses applicants’ eligibility, circumstances, and the nature and urgency of their housing needs. Based on this assessment, the department may:

- initiate an immediate response if required (for example, if an applicant is experiencing homelessness or domestic and family violence)

- offer housing assistance that suits their needs (for example, a bond loan or rental assistance)

- complete an application for social housing.

If a household is eligible for social housing, they join the register.

Social housing applicants (applicants) are households approved by the department for social housing in Queensland.

The housing register (the register) is a central register of all social housing applicants in Queensland. It contains information about an applicant’s housing needs, including their bedroom requirements and preferred housing locations.

The register is used to allocate tenancies in both government-managed and community housing. It is also a factor in planning new social housing builds and acquisitions.

Housing register snapshot

QAO analysis of data from the Department of Communities, Housing and Digital Economy.

The register is growing

As the private rental market becomes more competitive, more Queenslanders struggle to access safe, secure, and affordable housing. This has driven a steady increase in the demand for social housing since the department published its Queensland Housing Strategy 2017–2027.

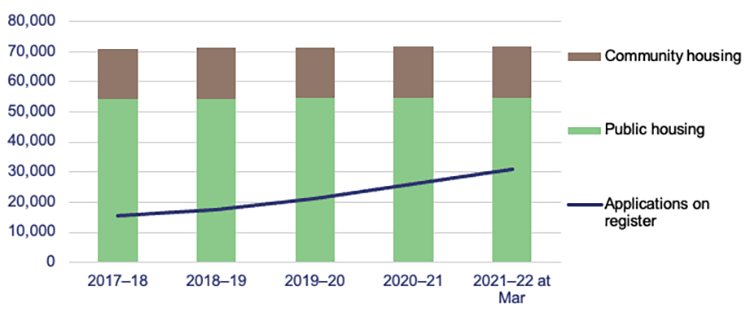

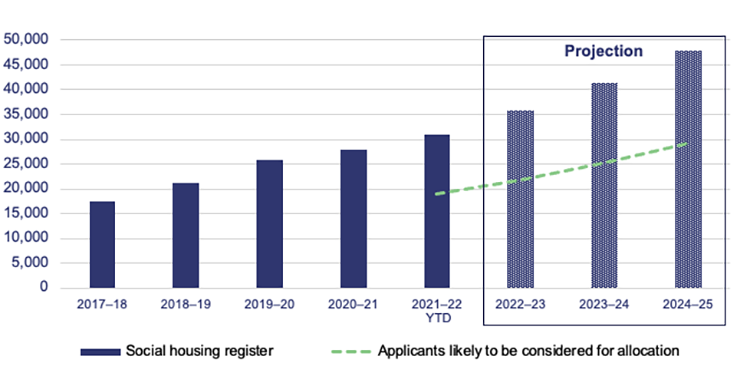

The total number of applicants on the register has increased by 78 per cent since 2017–18. In March 2022, the register contained 30,922 applicants. Figure 4A outlines the growth in the register since 2017–2018.

Note: 2021−22 YTD captures the housing register from 1 July 2021 to 31 March 2022.

QAO analysis of data from the Department of Communities, Housing and Digital Economy.

Applicants on the register can access and may have been offered other housing products and services, depending on their eligibility and circumstances. However, the department does not have a structured process to review applicants that have used other products to determine if they still have a need for social housing.

The department allocates social housing based on need

Applicants in very high need can be assisted quickly. For example, in the period 1 July 2021 to 31 March 2022, 871 applicants (23 per cent of all applicants in this period) were allocated housing within 3 months of applying.

Other applicants can remain on the register for many years. In March 2022, there were 2,433 applicants on the register who applied over 5 years ago, and 482 who applied over 10 years ago. Figure 4B outlines the average time spent on the register.

Note: the greater than 73 months category includes applicants who have been on the register for 73–303 months (up to 25 years).

QAO analysis of data from the Department of Communities, Housing and Digital Economy.

The average wait time in each social housing region is outlined in Appendix D.

All new applicants are in the very high need category

Since 2019, the department has classified all new applicants as very high need. The department advised this is because of the strengthened needs assessment against multiple and complex wellbeing indicators.

Prior to 2019, social housing applicants could also be assigned to low, moderate, and high need categories (lower need categories). In March 2022, there were 5,179 applicants on the register in these categories. These applicants are unlikely to be allocated housing and may not be aware that the department has strengthened its assessment process.

The department has also not clearly communicated its needs assessment approach to key industry and community housing stakeholders. For example, key stakeholders have advised that they do not understand the department’s needs categories.

Recommendation 1 |

| We recommend the department clearly communicates the needs assessment process it applies. This should include a proactive campaign to key stakeholders and consistent and complete information on the department’s website. |

Many applicants are unlikely to be allocated housing

Around 61 per cent of all applicants on the register are in the very high need category and can be contacted by the department. These applicants will be allocated housing first. Another 8 per cent can be contacted by the department but are in the lower need categories. These applicants joined the register prior to 2019 and the department needs to reassess their housing needs to determine their ongoing eligibility.

The remaining 31 per cent of applicants cannot be contacted by the department or have inactive applications. Figure 4C depicts the application status of all applicants on the register.

QAO analysis of data from the Department of Communities, Housing and Digital Economy.

All applicants are obliged to advise the department within 28 days of any changes to their circumstances. In 2021, the department attempted to contact all applicants to discuss the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on their housing, health, and employment circumstances. Many applicants either ignored the department’s contact attempts or have not maintained current contact details.

The department did not attempt to contact applicants with inactive applications. These applicants appear on the register, but their applications are either incomplete or paused. Inactive or uncontactable applicants should remain in the system, but the register should be limited to applicants who are likely to be considered for a housing allocation.

The department intends to review all applications

The department approved a new application management policy in October 2021. Under this policy, the department will regularly review the needs and eligibility of all social housing applicants. The department will initiate a review if an applicant has not made contact for 12 months.

The department’s review policy does not include fully automated processes to use data sharing or matching. For example, after a customer has given consent, the department uses Centrelink’s income confirmation service to manually update its system. An automated process would allow the department to proactively initiate conversations with applicants when their needs change.

The department should also consider using broader communication methods to connect with applicants to review and update their records on the register. This can include exploring digital channels like social media, online services and/or self-service online portals.

Recommendation 2 |

| We recommend the department periodically confirms the ongoing eligibility of all social housing applicants and updates the register as needed. Applicants who the department determines are uncontactable, or have inactive applications, should not appear on the register. |

Housing need is not always recorded correctly

During pathway planning conversations, the department will apply a ‘flag’ to an applicant’s record if they are in government priority need groups. These groups are part of the Queensland Housing Strategy 2017–2027 and include people who are homeless or at risk of homelessness and people experiencing domestic and family violence. These applicants may be prioritised for housing.

We examined a sample of applications and found that around 22 per cent did not have needs flags recorded in the system despite belonging to a government priority group. Some of these applicants may be overlooked for housing support, including a social housing allocation, due to missing needs flags.

Around half of the applications we examined were also missing evidence of second officer review, as required under the department’s procedures. This is an important step to confirm a social housing application is completed correctly. Second officer reviews may also identify missing needs flags and will go towards mitigating risks of inconsistent treatment of applicants.

Recommendation 3 |

| We recommend the department consistently completes and reviews all new housing applications. |

The department does not forecast growth of the register

Many social and economic factors drive the need for social housing. As the private rental market becomes more competitive, many Queenslanders will struggle to access secure and affordable housing. This may be compounded by the increasing cost of living, interstate migration, natural disasters, and major events such as the 2032 Olympics.

The department does not have a model to predict what the register will look like in coming years at the state and regional levels. This information would enhance the department’s understanding of whether its initiatives will meet future demand.

For example, if the register continues to grow at its average annual rate of 15.6 per cent, it will increase to around 47,800 applicants in 2025. However, if the department updates the register to only include applicants who are contactable and are in the very high need category, the actual number could be much lower.

Figure 4D shows 2 scenarios: the first shows the department’s current trajectory with the existing register; the second shows the trajectory if the department updates the register to contain only applicants who are likely to be considered for a housing allocation (those in very high need and able to be contacted). This is a conservative projection based on historical growth rates since 2017–18. It does not account for other external factors that could drive greater demand for social housing, including rising interest rates and increased net migration.

QAO analysis of data from the Department of Communities, Housing and Digital Economy.

Recommendation 4 |

| We recommend the department models future demand for social housing at the state and regional levels, incorporating historical and predictive analysis that includes social, economic, and environmental factors to inform its planning, investment, and service delivery. |

Applicants can also access help with renting

Applicants on the register can apply for rental support in the private market. For some social housing applicants, this is a stop-gap measure while they wait for long-term housing. For others, private rental assistance may mean the applicants no longer need social housing.

The department does not evaluate the success of these initiatives for the applicants on the register. For example, the department does not review the number of times an applicant receives private rental support and whether the assistance is reducing their need for social housing.

Without evaluating outcomes, the department cannot assess the effectiveness of private rental support or have confidence that applicants receiving assistance still require social housing. These evaluations could inform the department’s initiatives to reduce demand for social housing.

5. Social housing allocations

This chapter examines how the Department of Communities, Housing and Digital Economy allocates housing to people on the housing register (the register). We outline the department’s housing allocation process and examine how the department manages allocations over time to maximise housing outcomes.

Housing allocations

Social housing can only be allocated to applicants who are on the register. Allocation can happen through a shortlist offer, a manual offer, or a community housing offer. The type of housing offer is determined by the applicant’s needs, the features of the vacant property, and an assessment by departmental staff. All housing offers require confirmation of the applicant’s eligibility and a second officer review before being made to an applicant.

Shortlist allocations

When a government-managed property becomes available, the department can generate a shortlist of suitable applicants from the register. The shortlist will include applicants who match the vacant property’s location and number of bedrooms. The shortlist can be filtered to include factors such as disability and domestic and family violence.

Applicants with very high housing need are at the top of the shortlist, organised by the earliest application date. An offer can be made to the first suitable applicant on the shortlist. If the first applicant is no longer suitable or cannot be contacted, the offer is made to the next suitable applicant.

Manual allocations

Social housing can be manually offered to any applicant on the register. The department may make a manual offer to:

- respond to an applicant’s urgent or immediate housing need

- transfer a current social housing tenant to a more suitable property

- fill a vacancy in circumstances where a shortlist allocation would be unsuitable (for example, to match a particular applicant to a property with unique accessibility modifications).

Community housing allocations

The department is notified when a community housing dwelling becomes available. It refers 3 suitable applicants from the register to the community housing provider, based on the details of the vacant property. The referral may comprise of shortlisted or manually identified applicants. Community housing providers select an applicant from the department’s referral.

Community housing providers may contact applicants to seek further information, or they may ask the department to provide additional referrals. Community housing providers may also nominate an applicant from the register they consider suitable for a vacancy.

The allocation process needs improvement

The department is required to perform a pre-allocation check when making a housing offer, to confirm that an applicant’s need status and eligibility have not changed. We examined a sample of allocations and found that 18 per cent did not have a pre-allocation check on file.

The department also requires the pre-allocation check to be reviewed by a second officer. There was no evidence of second officer review for 20 per cent of the pre-allocation checks we tested. Without consistent pre-allocation checks, the department cannot be sure that applicants are appropriately screened before allocation.

Recommendation 5 |

| We recommend the department consistently performs pre-allocation checks through a systems-based process. |

The department prioritises applicants in urgent need

The department identifies certain applicants for priority allocations. These are applicants on the central housing register who have urgent, serious, and extraordinary circumstances that:

- place their safety and wellbeing at risk, such as domestic and family violence

- cannot be adequately resolved in the short term using other housing products and services

- can only be addressed through an urgent social housing response.

These applicants are identified through the assessment process, including conversations with applicants and referrals from support services.

Each housing service centre maintains a local spreadsheet that lists applicants for priority allocation in their region. This limits the department’s oversight of all applicants needing priority allocations across the state. It also prevents neighbouring social housing regions from easily sharing information about applicants needing priority allocations.

Most housing service centres require a manager’s approval to classify an applicant for priority allocation. However, there are no standard criteria to assess these applicants for priority allocation. The assessment relies on the judgment of departmental staff and varies across locations.

A centralised process would give the department greater visibility of applicants needing priority allocations. It would also allow the department to implement standard processes across all housing service centres. The department advised this is in development.

Recommendation 6 |

| We recommend the department implements a consistent process to identify, approve, record, and monitor applicants on the register for priority allocations across the state. |

Managing allocations

The average length of a social housing tenancy is close to 10 years. During this period, the housing needs of tenants are likely to change. This could include changes to their income, family composition, and accessibility requirements.

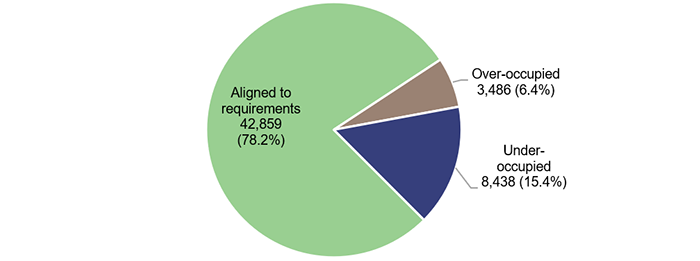

Some dwellings are under or over occupied

Under (or over) occupancy occurs when a dwelling has too few (or too many) people living in it. The department uses detailed criteria to determine when a house is over or under occupied. The criteria include the number, age, and gender of occupants. The department’s approach to identifying under and over occupancy is consistent with other jurisdictions.

Typically, a dwelling needs 2 or more spare bedrooms to be considered under occupied. Over occupied dwellings must require at least one additional bedroom. Figure 5A outlines the March 2022 levels of occupancy in social housing across Queensland.

QAO analysis of data from the Department of Communities, Housing and Digital Economy.

The department does not require tenants to relocate to more appropriate housing. It works with tenants to encourage them to move to smaller social housing properties where appropriate. This could be through inviting them to inspect new developments or helping with relocation expenses. This is a voluntary and an ad hoc process. The department’s policies and guidelines do not clearly set expectations that tenants may be required to relocate as their needs change over time.

Some tenants may be able to transition from social housing

With the right support, some tenants could foreseeably transition away from social housing. This would free social housing for other vulnerable Queenslanders.

The department does not proactively review and progressively transition tenants from social housing where appropriate. For example, it does not have a policy to use existing housing data or ongoing pathway planning conversations to identify tenants who could be supported with the department’s other products to transition to private rentals or home ownership.

Given the demand for social housing, the department should consider if its approach to tenancy management provides help to the Queenslanders in greatest housing need.

Recommendation 7 |

| We recommend the department reviews its approach to tenancy management to better respond to the changing needs of tenants in social housing. |

Recommendation 8 |

| We recommend the department uses structured conversations to identify and support tenants who can transition away from social housing. |

The department offers help with renting

The department also assists eligible customers through several rental initiatives. For example, some Queenslanders experience minor barriers to accessing or sustaining housing in the private rental market. They may struggle to identify affordable or suitable properties, or struggle to understand their rights and obligations as a tenant. Other people may just need financial advice and support to enter or sustain a tenancy in the private market. The department’s key rental support initiatives are outlined in Figure 5B.

| Initiative | Description of service | Number of recipients |

|---|---|---|

| Bond loans | An interest and fee free loan to cover the rental bond when moving into private rental accommodation. This loan needs to be repaid. | 9,604 |

| Bond loan plus | An interest and fee free loan to cover the rental bond and an amount equal to 2 weeks rent. The amount is a maximum of 6 weeks rent and must be repaid. | 1,492 |

| Rental grant | A rental grant is a one-off grant of 2 weeks rent for people in a housing crisis – it helps pay for the cost of moving into private accommodation. | 3,419 |

| Rent connect service | This service helps people who are struggling to access the private rental market due to non-financial barriers through:

|

5,634

1,194 |

| Helping hand head lease | The department leases a private rental property through a real estate agent and subleases to their customers. At a successful completion of the lease term, the department works on transferring the lease. | 133 |

| Rental security subsidy | This provides temporary financial support to the landlord to help sustain rental tenancy. The rent can be subsidised for a maximum of 6 months. | 160 |

| Total | 21,636 |

Note: The department cannot report how many recipients were also on the housing register during this period. Some recipients may also receive more than one service.

Department of Communities, Housing and Digital Economy data.

6. Social housing supply

This chapter examines how the Department of Communities, Housing and Digital Economy’s new investments align with the housing register. It includes the social housing portfolio in March 2022 and the department’s recent construction, redevelopment, and sale of existing properties.

Queensland’s social housing portfolio

Social housing snapshot

Social housing has slowly increased since 2017

The total number of social housing dwellings has increased by 978 since 2017–18. This includes new builds, redevelopments, and the sale of existing properties. In the same period, the register has increased by 15,265 applicants. Figure 6A outlines the growth in social housing dwellings relative to the increase in applications.

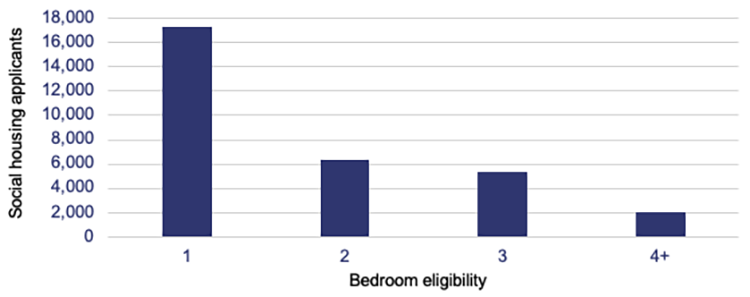

Most applicants are eligible for one or 2 bedrooms

Applicants cannot apply for housing that exceeds their eligibility and needs. The department has detailed criteria to determine how many bedrooms a social housing applicant is eligible for. For example, a single person is not eligible to apply for a 3-bedroom dwelling.

Over three-quarters of all applicants on the register are eligible for one or 2 bedrooms. Only 6.4 per cent of applicants are eligible for 4 or more bedrooms. Figure 6B details the bedroom eligibility of all applicants on the register.

QAO analysis of data from the Department of Communities, Housing and Digital Economy.

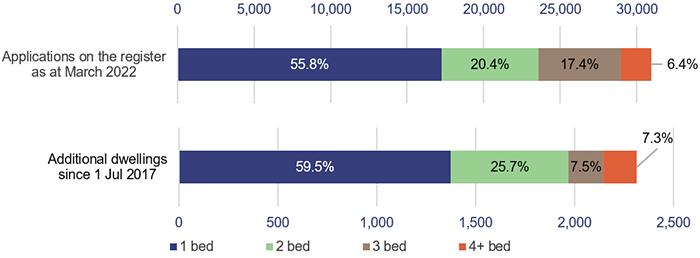

Recent construction has aligned with the demand profile

The department has completed construction on 2,314 dwellings since 2017. Around 85 per cent of new dwellings are one or 2 bedrooms. This is consistent with the requirements of applicants on the register (outlined in Chapter 4). Figure 6C shows this comparison for all new builds since 2017–18.

QAO analysis of data from the Department of Communities, Housing and Digital Economy.

New builds and sale of existing properties

New builds are delivered under the Queensland Housing and Homelessness Action Plan 2021–2025 and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Housing Action Plan 2019–2023 through the Queensland Housing Investment Growth Initiative (QHIGI). The department aims to commence building 6,365 new social housing dwellings by June 2025.

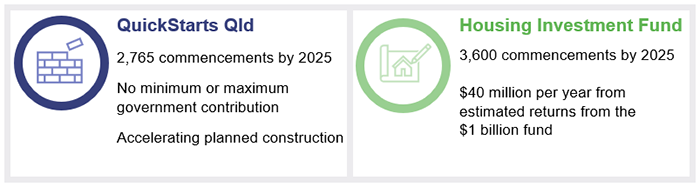

The QHIGI has 2 key construction initiatives, QuickStarts Qld (led by the department) and the Housing Investment Fund (led by Queensland Treasury), as described in Figure 6D. Many new builds under these initiatives will be delivered through the community housing sector. The number and location of community housing sector builds is not defined and will depend on the market conditions in each region.

New builds are planned in high need areas

The social housing application process captures key demand information, including household composition, bedroom requirements, and accessibility factors. Applicants can select up to 6 suitable housing locations. This provides the department with information on where social housing applicants prefer to live and their housing requirements.

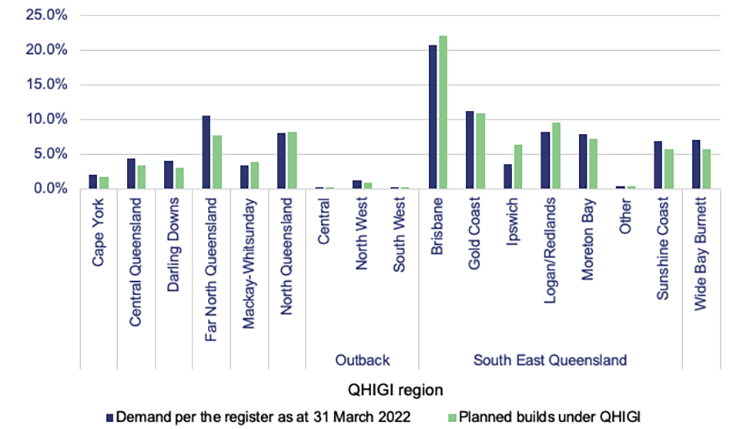

The locations of planned QHIGI builds broadly align with areas of demand on the March 2022 register, as outlined in Figure 6E.

QAO analysis of data from the Department of Communities, Housing and Digital Economy.

Some social housing will be sold or redeveloped

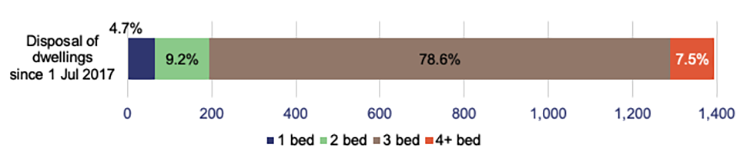

Sometimes it is no longer economical to maintain ageing dwellings and the department may redevelop the site (build new housing) or sell the property. The department may also sell stock that does not align with housing need in a region. For example, the department may sell a vacant house in an area that requires more 1-bedroom apartments.

Selling or redeveloping existing houses is part of the department’s asset life cycle planning. The decision to sell or redevelop social housing is generally made on an individual basis when stock becomes vacant. Proceeds from sales are reinvested in social housing. The department’s recent sales of properties are outlined in Figure 6F.

Planned builds alone will not meet the need for social housing

The department plans to commence building 6,365 new dwellings by 2025. This new supply will help address some demand on the register. However, even if these builds commence as planned, current trends suggest the number of applicants will far exceed new dwellings in 2025. To help Queenslanders in housing need, the department will need to build additional dwellings and/or expand its use of other products and services.