Overview

To deliver the public services and infrastructure Queenslanders rely on, the government needs to invest in technology. Unfortunately, it is difficult to deliver technology projects successfully. Many currently do not hit their deadlines, stay within budget, or achieve their objectives. This issue is not unique to the Queensland public sector—national and international reports highlight the problems faced by other governments in delivering new or upgrading existing services. The public sector can improve by examining the reasons behind the successes and failures of technology projects.

Tabled 30 September 2020.

Auditor-General's foreword

There has been a great deal of interest in the success and delivery of technology projects across the public sector. The Queensland Audit Office (QAO) prepared this report to share its insights with all entities so they can apply crucial learnings to each of their respective projects.

Given the value of the investments in technology projects, and the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, public sector entities must ensure that they learn from past experiences. The pandemic has reinforced the need for entities to take stock, and identify new, more efficient (technology enabled) ways of delivering their public services.

Earlier this year in my February report on the state’s finances, I reported that the Queensland Government’s financial performance has reduced, with expenses increasing at a greater rate than revenue. The current economic climate makes it more important than ever to ensure that the significant money invested in technology projects delivers value for the community.

This insights report builds on some of my past reports, which cover monitoring and managing ICT projects, digitising public hospitals, the reform of the state penalties enforcement registry, and health’s finance and supply chain management system. I recognise that it is not easy to successfully deliver technology projects. Other governments here in Australia and internationally have also had their share of technology project failures and are looking to increase their success rates.

The government’s hold on all non-essential new technology projects offers an opportunity for entities to consider the implications of COVID-19 on their priorities and operations so they can recalibrate. They now have time to ensure that they set up their projects to maximise success. To do this, they need to challenge and validate the need for their projects. This may require reassessing whether they have the right approach and skills.

As Queenslanders continue to become more reliant on working, learning, and doing business remotely, it will be essential for governments to use technology to transform their services. This has the potential to deliver savings through efficiencies in service delivery. I will continue to focus on technology transformations in my future reports.

Brendan Worrall

Auditor-General

In brief

|

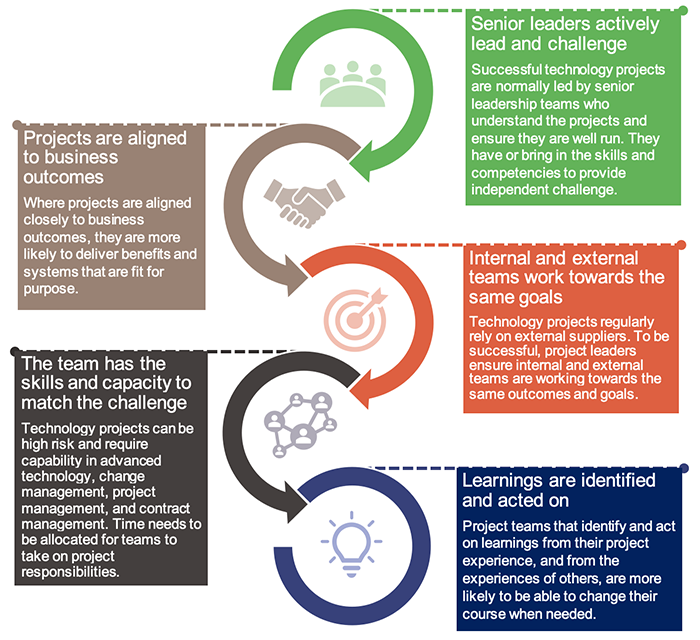

Technology is critical in the delivery of government services such as health and education, and the provision of support functions like payroll and finance. The COVID-19 pandemic has reinforced how important technology systems are in giving the public access to government services online. These systems depend on digital technology that is secure, reliable, and fit for purpose. However, technology does not stay the same. Upgrades and changes are needed, and they are invariably complex and difficult. Unfortunately, many technology projects currently do not hit their deadlines, stay within budget, or achieve their objectives. For this report, we have identified, from our audits and other research, five factors that, if managed and modified to suit, can improve the success of projects. They are summarised in Figure 1. No one factor is more important than another; it is the combination and integration of them all that can make a difference. |

Queensland Audit Office.

Actions

Insights from this report apply to all technology projects. All entities within the public sector can use the factors we have identified to improve the maturity of their processes to deliver technology projects. We have identified the following actions for the sector to consider.

| Public sector boards and executives |

1. Review their current portfolio of technology projects to re-confirm priorities ensuring that:

|

|

2. Ensure that for future projects involving external suppliers:

|

| 3. Ensure that current and future technology projects are set up with the right mix of skills and resources. |

| 4. Reflect on why projects have failed in the past and take timely actions to avoid making those mistakes again. Prior learnings must form part of the key considerations in managing project risks. |

1. How successful are technology projects?

To deliver the public services and infrastructure Queenslanders rely on, the government needs to invest in technology. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the critical role of technology in keeping governments connected to business, society, and their workforce. For example, secure and reliable technologies have been needed for:

- students accessing remote learning from home

- health promotion through advice and alerts about COVID-19

- promotion, assessment, and allocation of COVID-19 grants to assist affected businesses

- payroll processing for teachers, nurses, police, and other essential workers.

Most new technology services and products are complex and require entities to identify business outcomes, manage contracts, and monitor expenditure, timeframes, and integration.

Unfortunately, it is difficult to deliver technology projects successfully. This is not unique to the Queensland public sector. National and international reports highlight the problems faced by other governments in delivering new or upgrading existing services. The public sector can improve by examining the reasons behind the successes and failures of technology projects.

In February this year, in Queensland Government state finances: 2018–19 results of financial audits (Report 11: 2019–20), we reported that the financial performance of the Queensland Government has reduced over the last two financial years, with expenses increasing at a greater rate than revenue. In the current economic environment, it is more important than ever to ensure that investments in transforming critical government services deliver value for money.

The Queensland Government has put a six-month hold on all non-essential new technology projects. This can create a risk that public sector entities delay essential projects while they request exemptions. However, it offers an opportunity for them to reconfirm priorities, and ensure that they set up their projects on sound foundations. They can do this by challenging and validating the need for the project and whether they have the right approach and mix of skills and capabilities to provide oversight and deliver the business outcomes.

How much does the sector spend on technology projects?

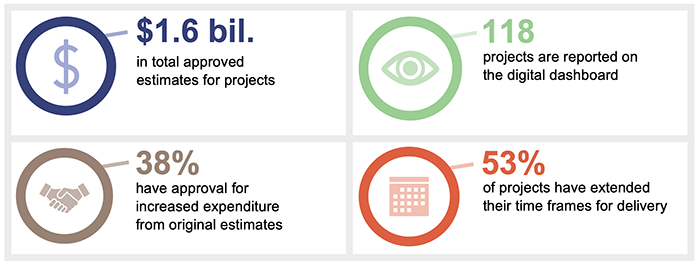

As at 30 June 2020, departments reported a total budget of $1.6 billion in current technology projects on the Queensland Digital Projects Dashboard (the dashboard—maintained by the Queensland Government Chief Customer and Digital Group). Departments decide (based on dashboard publishing criteria) which projects they will report.

The dashboard does not include technology projects of public sector entities other than departments—statutory bodies, government owned corporations, and local governments. We conservatively estimate that over $0.5 billion in approved budgeted expenditure for technology projects for these public sector entities is not reported on the dashboard.

We may examine these in future insight reports or audits, along with other projects on the dashboard. Figure 1A shows a snapshot from the dashboard.

Queensland Audit Office from the Queensland Digital Projects Dashboard.

Most Queensland Government technology projects reported on the dashboard cost less than $10 million, with an average estimated cost of $2.8 million. The three largest projects have budgets greater than $100 million. They are:

- Human Resources Information Solutions program—$101.3 million (the Department of Housing and Public Works)

- Integrated Electronic Medical Records program—$323 million (the Department of Health)

- Smart Ticketing Project—$371 million (the Department of Transport and Main Roads).

Given the large investment, senior leadership teams have an important role in actively leading technology projects and ensuring they achieve their outcomes.

This is the case for all technology projects, regardless of cost. Those worth less than $10 million individually still add up to a total of $265 million, which is 16 per cent of the investment portfolio reported on the dashboard.

Queensland Audit Office from the Queensland Digital Projects Dashboard.

How are projects performing against time and budget?

Departments are reporting on 118 technology projects. Of these, 55 (47 per cent) are currently tracking on time and 73 (62 per cent) on budget. Departments expect around:

- 26 per cent of projects to take at least 50 per cent longer to complete than expected

- 23 per cent of projects will cost 50 per cent more than expected.

Increases in time and cost could arise from a multitude of reasons, or it could be due to incorrect estimates at the start. Our analyses from the dashboard are in Figure 1C below.

Note: In calculating delays, we used the ‘approved end date’ from when departments first published the project as the reference point. To calculate the budget overrun, we used the cost that departments have reported as their ‘commencement allocation’ as the reference point. Some projects had budgets less than original costs; they are included in the ‘no increase’ category.

Queensland Audit Office from the Queensland Digital Projects Dashboard.

Some projects take longer to complete than originally planned but still meet their budget. The dashboard does not show how often this occurs or why it happens. Figure 1D is a case study of the Human Resources Information Solutions program, which transferred to the Department of Housing and Public Works in December 2017 as part of the machinery of government changes. This case study is an example of a multi-year program that took twice as long to complete than planned but had no change in budget. It delivered different products than planned and did not achieve all its objectives.

| Human Resources Information Solutions program |

|

The Human Resources Information Solutions program was established to replace the outdated payroll system used by Queensland Corrective Services, Queensland Fire and Emergency Services and the Queensland Ambulance Service. At the start, it included several projects to: stabilise the existing system; prepare data and processes for new systems; and develop a business case for the program. The budget for this initial part was $1.5 million. In September 2012, a budget of $100 million was approved over four years (2012–2016) to replace the payroll system. The proposal for the new solution was to have an external service provider processing transactions and providing the systems for payroll and human capital management (staff recruitment, performance, and development). In March 2015, after a change in government policy, the program changed so that all of the entities would:

|

Queensland Audit Office from Department of Housing and Public Works documentation.

What is the success rate of technology projects?

Our research shows there is a high rate of failure in delivering technology projects across the world. In 2018, the McKinsey Center for Government did a survey of 3,000 public officials across 18 countries and found that 80 per cent of public sector transformations fail to meet their objectives.

The Australian Institute of Project Management reported similar results in a joint global survey with KPMG and the International Project Management Association. With 500 respondents from 57 countries, this survey reported that only 19 percent of the organisations delivered successful projects most of the time.

Clearly, it is not easy to successfully deliver technology projects as shown in examples below:

- In 2019, the Australian National Audit Office issued a report on the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission’s administration of its biometric identification services project. The commission cancelled this project after two years and renewed the contract with its existing supplier. It had spent $34 million.

- In 2017, the Auditor-General of Canada found that the government’s new payroll system was not processing pays correctly. The project had a budget of CAN$310 million and took seven years to implement. However, 16 months after implementation unresolved pay errors totalled half a billion Canadian dollars. The Canadian government estimated it would take three years and cost an additional CAN$540 million to resolve the payment errors.

- In 2017, the National Audit Office in the United Kingdom reported on the Ministry of Justice’s new generation electronic monitoring program. Five years after initiating the project, the ministry renewed the contract with its existing supplier. It had spent £60 million.

Recent examples of cancelled projects in Queensland

The Queensland Government has also seen costly technology project failures, including the following:

- In 2018, the Department of Employment, Small Business and Training cancelled its Training Management System project after spending an estimated $34 million.

- In 2019, Queensland Treasury cancelled its State Penalties Enforcement Registry (SPER) technology project after spending $52.7 million.

- In 2020, the Department of Health cancelled its Laboratory Information System project after spending $51 million. (Further details on this project are in Appendix B.)

These projects did not deliver the systems needed and have collectively spent more than $138 million. Cancellation can be appropriate, but it needs to be at the right time before significant losses accumulate, and senior leaders should feel empowered to consider this option when it is in the best interests of the state.

If agencies repeat past practices, we can expect a significant proportion of Queensland’s technology projects to cost more and be delivered late or not at all.

2. How can we improve success rates of technology projects?

Having recognised the challenges in delivering technology projects successfully, we:

- analysed our prior audit reports and several national and international reports

- consulted with technology leaders, including those who have led technology projects in the public and private sectors

- reviewed five case study projects that are currently reported on the Queensland Digital Projects Dashboard (the dashboard). The key facts on the five case study projects, including time frames and project costs, are in Appendix B.

Based on this work, we have identified five factors, which, if managed and monitored throughout the life cycle of projects, can improve the chances of success. They are:

- senior leaders actively lead and challenge

- projects are aligned to business outcomes

- internal and external teams work towards the same goals

- the team has the skills and capacity to match the challenge

- learnings are identified and acted on.

Individually, each of the factors is valuable, but for projects to be successful, all the factors must be present, working together and integrated into the existing project management methodologies and controls. Each project is different, and senior leaders can determine how best and with what rigour to apply them to projects.

In this chapter, we discuss the factors and give examples of where they have made a difference to the success or failure of projects.

Senior leaders actively lead and challenge

|

Insight Successful technology projects are normally led by senior leadership teams who understand the projects and ensure they are well run. They have or bring in the skills and competencies to provide independent challenge. |

Technology projects create significant organisational change and carry a high risk of failure. To deliver them effectively, senior leadership teams need to take ownership, lead the change program and ensure it is set up for success. As part of this, leaders may need to supplement their own skills by bringing in experts to provide independent challenge.

Key areas for senior leaders to actively challenge include:

- the organisation’s ability to deliver the number of change programs that are being delivered at the same time

- the impact of change on people, process, and technology, and how this sits with the organisation’s appetite for change

- project planning, business cases, progress reports, and performance—in terms of whether they are realistic and based on sound evidence.

As part of our research, we identified a detailed report on a technology project to replace an old billing system: Sydney Water Customer Experience Program—Lessons to Emulate (CxP). The Digital Investment and Assurance unit within the New South Wales Department of Customer Service published this case study on its website, to share learnings. The New South Wales Digital Investment and Assurance unit, which provides similar services as the Queensland Government Chief Customer and Digital Group, partnered with Sydney Water to document the case study.

In Figure 2A we have included a brief description of the program and some of its key success factors from the case study report. We have not audited this program. Information in Figure 2A is solely based on the case study report.

| Customer experience program |

|

Sydney Water identified that its 30-year-old billing system was at major risk of failure. In 2016, it established a customer experience program that included replacing the billing system. Some of the key success factors in the report included:

|

ICT Digital Investment & Assurance, Department of Customer Service, New South Wales— Sydney Water customer experience program—Lessons to emulate.

Projects are aligned to business outcomes

|

Insight Where projects are aligned closely to business outcomes, they are more likely to deliver benefits and systems that are fit for purpose. |

Many technology projects in government are started because there is a need to avoid the cost of a failure in a legacy system (an old system that is no longer supported by its developer). Public sector entities often replace their legacy systems with new solutions that have the potential to deliver broader business outcomes than the existing system. They may improve efficiency and effectiveness in delivering services or they may enable richer insights into performance against key government priorities.

Projects will be successful and achieve these benefits if employees embrace the new solution and use it effectively. To this end, project leaders need to integrate business operations with new and emerging technologies throughout the life of the project.

They could do this by:

- having subject matter experts from the business as part of the project from the start

- involving business teams in evaluating and using new solutions as they adapt the business processes to the new ways of working

- monitoring the transition through the changes and adjusting the pace at which users adopt and use the system.

Figure 2B explains how the Department of Transport and Main Roads worked towards achieving alignment between business teams, suppliers, and a project team. This case study is about only one aspect of the project. The department documented and addressed several learnings during the project. The project is still in progress and the department can make a full assessment of project performance when it is complete.

| Vessel traffic services project |

|

The Department of Transport and Main Roads involved its relevant business units in preparing a request for tender for replacing its vessel traffic systems (for services related to tracking and communicating with ships). After selecting the preferred supplier, and before signing the contract, the project team worked with the supplier and the business units to assess the gap between existing processes and the proposed solution. This process highlighted that:

The project team used this phase to standardise the business processes as much as possible and to understand how the system would work in their business environment. The department reports that, as a result, all parties were clearer about how the system and business processes needed to adapt. |

Queensland Audit Office from Department of Transport and Main Roads project documentation.

Where system changes are large components of the project, it is useful to understand and agree on a minimum acceptable product (one that has the minimum features for the core business) from the start of the project. This enables the business to take an early look at the system and provide feedback as needed.

Another key aspect of effective alignment is to build agility into the project, so it is responsive to the business needs and is continuously integrating and delivering solutions. This is especially important at the program level, as programs often run over multiple years and have several projects that contribute to program outcomes. To continually align with changing business needs and outcomes over time, successful program leaders regularly review their priorities, while still delivering business benefits.

Figure 2C is a case study on how the Department of Environment and Science developed a program with built-in agility and flexibility so it could pivot in line with changes in business, economic, and technology environments. This case study is about only one aspect of the program. The program is still in progress and the department assesses project performance as it progresses.

| Accelerating Science Delivery Innovation program |

|

This program involves transforming the delivery of scientific information in Queensland. The program includes a series of projects to enable new and more accessible insights and data to support quality decision-making across government. It is also used in the scientific community. The department designed this program to be flexible, and it reviews its projects annually for funding. It designed the individual projects to deliver value as they progress, so when the funding finishes for each project, it can be re-prioritised, along with the other projects in the program. This enables the department to regularly review the relevance of the projects to its strategic business outcomes. It reports that it is progressively enhancing its technology infrastructure and implementing digital collaboration tools for the scientific community. |

Queensland Audit Office from Department of Environment and Science program documentation.

Internal and external teams work towards the same goals

|

Insight Technology projects regularly rely on external software providers. To be successful, project leaders ensure internal and external teams are working towards the same outcomes and goals. |

Technology projects regularly rely on external software providers, who can sometimes be based internationally. This reliance on people and capabilities outside of the organisation (and sometimes out of the country) can be appropriate, but can add complexities, such as differing legislation, language, culture, and ways of working.

To engage effectively with external parties, successful project leaders ensure the contracts:

- include incentives to deliver the right outcomes

- include clear a description of the solution and confirm the time and effort needed for it to be ready for use.

For the projects to be successful, project leaders foster a one-team culture, with everyone having the same goal of delivering the project to the required standard. This means working together to solve problems and implement an effective strategy.

Figure 2D is a case study of the Election Gateway Project. It highlights the challenges the Electoral Commission of Queensland had in working with an external supplier to deliver the system. This project is currently in its delivery phase. A parliamentary inquiry reviewed the online publication of preliminary and formal counts of the votes cast in the local government elections and the state by-elections held on 28 March 2020. Our report does not include a detailed review of the project itself or of any technical issues. The case study describes one of the difficulties the commission faced when developing and implementing the system.

| Election Gateway Project |

|

In 2015, the Electoral Commission of Queensland started a project to replace its legacy system for most of its electoral planning, operations, and reporting processes. It intended to purchase a commercial off-the-shelf product and it knew from the start that the system would need customisation. The international supplier established the development team offshore. As the supplier did not have experience with the Australian elections systems, it took time for them to understand the requirements. At the start, the supplier did not have the measures and level of transparency for project performance that the commission expected. Five months after signing the contract, the commission experienced delays in detailed design and technical documentation. To progress the project, the commission worked with the supplier to assess the effort needed to achieve the milestones. It brought in additional technical expertise in the internal team to increase overall capacity. Then the commission identified the priority functions needed for the upcoming local government elections and the state by-elections in March 2020. It adopted a phased approach to deliver the system. The commission documented several learnings during the project. One of the learnings was to ensure that all components, including backup components, of the end-to-end solution are fully tested prior to going live. |

Queensland Audit Office from Electoral Commission of Queensland documents.

To foster strong relationships with external teams, engaged project leaders ensure the preferred supplier and the project team have a common understanding of how the software aligns with the business outcomes, prior to signing the contract. As part of this, it is useful to determine the minimum acceptable product.

This can help in:

- balancing risks and rewards across all parties and creating incentives for performance

- aligning milestone payments with agreed deliverables as they relate to progress in delivering the solution

- clearly articulating roles, responsibilities, time frames, and deliverables for all parties throughout the contract.

Figure 2E is a case study showing what happened when an organisation’s and a supplier’s assumptions about implementation time frames were not aligned. This lack of alignment between internal and external teams has caused a pause in the project, while senior leaders try to negotiate a way forward with the suppliers.

| Fleet management system replacement |

|

In 2017, QFleet (part of the Department of Housing and Public Works) began a project to replace its fleet management system. As part of the procurement process, it held workshops with the suppliers and the business to gain a thorough understanding of the gap between the business needs and what the software could provide. After signing the contract, QFleet worked with the supplier to define the project for an implementation plan and delivery dates. At this stage, it noted that the supplier’s delivery plan was not the same as its own. Negotiations with the supplier about delivery plans for the project failed. For this reason, the project was paused. The Queensland Government Chief Customer and Digital Officer is assisting in negotiating with the supplier for a way forward to deliver a minimum acceptable product. |

Queensland Audit Office from Department of Housing and Public Works project documentation.

The team has the skills and capacity to match the challenge

|

Insight Technology projects can be high risk and require capability in advanced technology, change management, project management, and contract management. Time needs to be allocated for teams to take on project responsibilities. |

Successful leaders recognise the importance of taking an integrated approach to selecting the project team. They know they require a mix of skills including advanced technical capabilities, change management, project management, business knowledge and contract management.

They do this by involving subject matter experts who have proven capability in delivering similar projects. When engaging external suppliers, successful project leaders ensure there is a good cultural fit and that the supplier provides the talent and skills they promised.

To match the capability needed with the challenge, successful project leaders ensure:

- the right people are available when they need them and have sufficient time to manage their responsibilities

- the team has the right mix of qualifications and experience

- the team can balance its focus on both the project and the business requirements, and has the flexibility to adapt with change

- team members, including suppliers, are incentivised to keep to budgets and time frames.

Figure 2F is a case study of one aspect of the Human Resources Information Solutions program, showing how the Department of Housing and Public Works matched capability to the challenge for the payroll component of the program. This case study is about transitioning the Queensland Ambulance Service from an old payroll system to a supported payroll system.

| Human Resources Information Solutions program: payroll system |

|

The Human Resources Information Solutions program was to transition the payroll systems for four entities to a supported system and deliver a human capital management (staff recruitment, performance, and development) solution for three of the same entities. This case study covers the transition of payroll for the Queensland Ambulance Service to a supported system. This payroll involves a rostered solution with multiple awards, allowances, and special conditions. The parties involved in delivering the payroll solution for Queensland Ambulance Service were:

While the payroll program board was accountable for delivering this project, the Queensland Ambulance Service also established an internal reference group. Project documents show that this group provided input and support to progress the project. Project documents also show that the team included people with:

In the project closure report, the project manager commented that there was continued commitment from all the team members to deliver the project successfully. |

Queensland Audit Office from Department of Housing and Public Works program documentation.

Learnings are identified and acted on

|

Insight Project teams that identify and act on learnings from their project experience, and from the experiences of others, are more likely to be able to change their course when needed. |

Lessons learnt and success factors for technology projects are widely published for international, national, and local projects. However, our research shows that senior leaders find it difficult to ensure lessons are learnt and avoid repeating mistakes of the past.

Most projects in scope for this report have registers for lessons learnt, including lessons discussed at workshops, findings from various types of reviews, and lessons from project team members. Some registers include action items that project teams mark off when completed. However, these processes do not seem to result in learnings about the decisive actions business and project leaders need to take to avoid mistakes that have been made before.

Leadership teams need to step back and ensure the project teams use the learnings on why projects have failed, to manage current project risks. Leadership teams also need processes to confirm that project teams:

- scan the environment for similar projects, document their learnings, address (at the start of a project) any risks experienced in other projects that are likely to occur in their project

- run workshops on internal lessons learnt and take actions to correct the course as necessary while the project is in progress

- share key learnings with all stakeholders and other project teams within government

- document how they addressed key lessons learned in project closure reports and make it available for other projects.

Figure 2G highlights the importance of identifying and acting on project learnings. It shows that the Department of Health had processes in place to discuss review findings and lessons from other projects. However, it missed opportunities to:

- challenge the business case throughout the life of the project on the rationale for replacing the existing system

- take sufficient and timely actions to affect the level of project change that was necessary when reports showed that the project was deteriorating against its key performance indicators (since January 2018).

| Laboratory Information System project |

|

This project involved replacing the Department of Health’s laboratory information system with a commercial off-the-shelf system for its 36 laboratories across the state. The department endorsed the business case in November 2017. The department undertook multiple reviews throughout the project. It documented learnings about governance, communication, resource management, and the supplier’s ability to deliver the product. In March 2019, the department took action to restructure the project and increase its interactions with the supplier at senior levels. In September 2019, when the department undertook an options analysis for a way forward with the supplier of the new system, it found many learnings, including:

The department still has the risk of an ageing laboratory information system that it may need to address in the future. |

Queensland Audit Office from Department of Health project documentation.