Overview

The Queensland Police Service plays a pivotal role in keeping our communities safe, but is facing increased pressures and growing demand for its services. This stems from changes in population and the nature of crimes; new legislation and government initiatives; and major challenges, such as government responses to the pandemic, natural disasters, and international sporting events. It needs a strategic approach to growing, optimising, and upskilling its workforce to meet future demand.

Tabled 30 November 2023.

Report on a page

The community expects a lot from police. The Queensland Police Service (QPS) plays a pivotal role in keeping our communities safe 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. However, it is facing increased pressures including a growing demand for its services. The pressures stem from changes in population and the nature of crimes; new legislation and government initiatives; and major challenges, such as the response by governments to the pandemic, natural disasters, and international sporting events, like the Brisbane 2032 Olympic and Paralympic Games.

In this audit, we examined how effectively and efficiently QPS identifies and manages demand for its services.

Understanding demand for service

QPS does not have a complete picture of all demand for its services. It has a demand model, but the information it currently collects is mainly based on responding to calls for service (assistance). It does not capture the time officers spend on proactive policing, administrative tasks, and non-frontline work. This limits its ability to effectively prioritise the efforts of its officers to meet overall current demand. It also limits its ability to forecast and plan for a workforce to meet future demand. QPS has not effectively identified emerging and changing demands or considered the impact these will have on its resourcing.

Planning a workforce for the future

QPS does not have a strategic approach to workforce planning. Its workforce growth target is not informed by evidence-based analysis of demand for services. It stems from a 2020 Queensland Government election commitment to increase the QPS workforce by 2,025 (including 1,450 police officers) by the year 2025. QPS is not on track to meet this target, as attracting and retaining staff is a challenge. Higher-than-expected attrition rates, a change in society’s perceptions of policing as a career, and recent shortages of labour resources have all contributed. QPS has started implementing strategies to attract and retain more staff. It has also merged some central commands and restructured business units to change some roles to free up police officers to focus on frontline services. But it needs a strategic approach to growing, optimising, and upskilling its workforce if it is to meet future demand.

Responding to calls for service

A major part of current demand for policing involves responding to calls requesting police services. Since 2016, the calls have increased by 30 per cent, with the police officer head count increasing over the same period by 25 per cent. QPS prioritises its efforts towards responding to these calls, based on level of urgency. While it attends most calls requiring attention, it does not meet its response time targets set for high-priority calls. In 2021–22, QPS aimed to respond to 85 per cent of its high-priority calls from 000 within 12 minutes. But it met this target only 78.2 per cent of the time. Responsiveness varies between regions due to factors such as remoteness, distance, and the availability of resources.

Rostering police resources to meet demand

QPS rostering practices vary across regions and often do not match demand for service. The greatest number of reported incidents occurs between 5:00 pm and 11:00 pm, particularly at weekends, but the availability of officers does not align with these peak times. During high-demand periods, frontline officers typically spend less time at incidents. QPS has not assessed whether this results in compromised quality of service provided during these periods.

1. Audit conclusions

The Queensland Police Service (QPS) has seen an increasing and changing demand for its services. It is operating in an environment of shifting community expectations; technological changes; and increasing crime rates, population, and economic uncertainty. Domestic and family violence and mental health incidents have increased, and these require specific training and skills for police officers. In addition, recent reviews and inquiries have led to many reform activities and the need to implement subsequent recommendations.

QPS has taken a short-term focus in addressing these issues. It lacks strategic workforce planning and does not have a holistic view of current and future demands. Also, it has not evaluated its workforce needs and capabilities to improve its ability to meet demand. As a result, it is limited in its ability to make informed and proactive decisions about prioritising and allocating resources.

It cannot effectively plan for:

- the number of police officers, equipment, and infrastructure it needs to best deliver services

- where and how to best deploy its resources.

QPS is not meeting current demand for its services. While it attends most calls that require attention, it does not meet its response time targets for high-priority calls. Available resources focus, understandably, on calls for service, but this often means less time is spent on proactive policing – activities to reduce crime, such as preventative patrolling and road safety awareness campaigns.

In addition to growing demand, police deal with increasingly complex incidents, which puts pressure on the system. This is reflected in the challenges QPS faces in attracting and retaining officers and it results in increased overtime. Unlike other states in Australia, Queensland has a mandatory retirement age of 60 years for sworn police officers (a legislative requirement under the Police Service Administration Act 1990). This presents a further restraint on resourcing.

QPS needs to become more agile and flexible so it can better manage demand while also addressing challenges related to efficiency, staff wellbeing, public expectations, and staff recruitment. It requires strategic planning and modelling to effectively identify service demands and manage them. This includes reviewing all positions or tasks to identify those that do not require police powers and could be done by staff members. It also means understanding and better prioritising the tasks consuming the time of police officers. Without a more strategic approach, QPS will remain trapped in a cycle of struggling to meet current demand pressures and failing to plan for the long term.

In 2023, QPS closed the service delivery program on which it had spent $25.9 million and which had showed promising outcomes. It has no planned alternative to addressing the service delivery issues this program was designed to solve. Its reason for closing the program was to avoid workforce fatigue in responding to recent inquiry recommendations. This is a lost opportunity for addressing its shortfalls in meeting current and future demand and for reducing the pressure on QPS as a whole and police officers in particular.

The recommendations from this audit will involve some initial work. However, acting on them will not only help QPS measure and manage the effectiveness of its services, but also reduce uncertainty and stress by clearly identifying problems and solutions across the organisation.

2. Recommendations

|

Predicting and planning for demand (Chapter 4) |

|

We recommend that the Queensland Police Service (QPS):

|

|

Meeting the current demand for services (Chapter 5) |

|

We recommend that the Queensland Police Service (QPS):

|

Reference to comments

In accordance with s.64 of the Auditor-General Act 2009, we provided a copy of this report to the relevant entity. In reaching our conclusions, we considered its views and represented them to the extent we deemed relevant and warranted. Any formal responses from the entity are at Appendix A.

3. Queensland’s policing environment

The Queensland Police Service (QPS) deploys its workforce across the state to keep our communities safe. To do this well, it needs to understand the key drivers of demand for its services and effectively organise its workforce to meet those demands.

Police services

QPS provides services designed to uphold the law and assist the community, including in times of emergency, disaster, and crisis.

QPS as an agency has responsibility for 2 service areas:

- Crime and public order: it upholds the law by working with the community to stop crime and make Queensland safer

- Road safety: it contributes to stopping crime and making the community safer by promoting road safety, reducing road trauma, and providing evidence-based enforcement.

The policing environment in Queensland is currently characterised by rapid change and increasing complexity. Shifting community expectations, an increasing population, rapid technological innovation, and new modes of offending are impacting on traditional approaches to policing and service delivery. Queensland also remains at risk from natural disasters and severe weather events that present threats to public safety – and have implications for QPS.

Queensland Police Service – structure and staffing

QPS is divided into 6 areas known as portfolios. These include regional operations, regional services, and specialist operations. Its key functional areas for services are:

- operations across the state, made up of 7 regions, split into 15 districts and 341 stations. Geographical clusters of stations are known as patrol groups

- command services that support regional operations, such as road policing; forensic services; and domestic and family violence, and vulnerable persons services

- specialist operations, including crime and intelligence command, and security and counter-terrorism command

- corporate services, including a policy and performance division, frontline and digital services, and organisational capability command.

The following snapshot in Figure 3A shows the total QPS staff expenditure in the 2022–23 financial year and the workforce breakdown as of February 2023.

Note: FTE – full time equivalent.

Queensland Police Service financial statements 2022–23 and human resources data.

Police officers are sworn officers who take an oath to uphold law and order, community safety, and quality of life. They hold and exercise police powers, such as powers of arrest.

Staff members are public servants who do not hold any police powers.

Recruits are unsworn employees who are undergoing training to become entry level police officers.

Protective security officers take an oath as a protective security officer and provide security services to government buildings.

Liaison officers establish and maintain communication between the community and police to foster co‑operation and understanding, and to improve community access to policing services.

As of February 2023, police officers made up 71.8 per cent of the total police workforce. Of the 11,972 police officers, 8,953 were allocated to the 7 regions, with the remaining 3,019 allocated to specialist operations and corporate services. This means 74.8 per cent of the total police workforce were police officers allocated to a regional command.

The demands on police

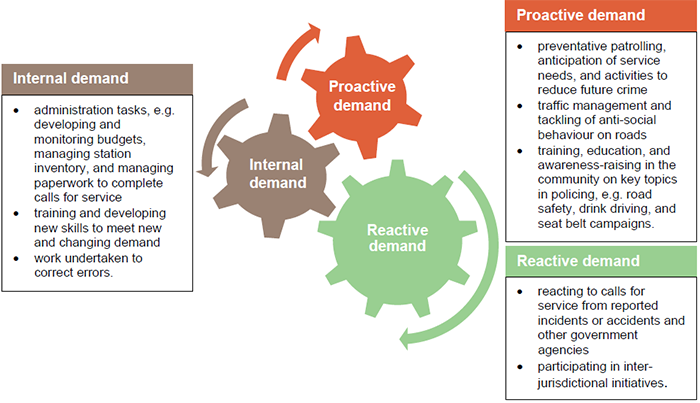

Policing demand can be broadly categorised as:

- reactive (responding to incidents/calls for police assistance)

- proactive (preventative activities)

- internal (activities QPS generates internally).

Activities within each category can reduce or generate work for other categories. For example:

- proactive work can reduce reactive demand

- strategic internal work can reduce reactive work

- reactive and proactive work can create more internal demand.

Figure 3B shows the types of activities in each of the demand categories.

Note: These activities exclude corporate functions.

Queensland Audit Office, derived from a Griffith University paper entitled ‘Understanding the concept of ‘demand’ in policing: a scoping review and resulting implications for demand management’.

4. Predicting and planning for demand

This chapter is about how QPS identifies and assesses the current, changing, and emerging demands for its services. It is also about how it plans for its future workforce and for capability to meet those demands.

Understanding demand

QPS operates in a complex and diverse environment and strives to meet its demands with its available resources. To manage current, changing, and emerging demand, QPS must fully understand the drivers impacting on its services, including:

- an increasing focus on certain types of crime (such as domestic and family violence, and youth crime) and community policing (such as welfare checks)

- changing demographic and socio-economic factors

- the implications of major events, for example, the Brisbane 2032 Olympic and Paralympic Games; and severe weather events

- emerging technologies, such as

- the rapid increase and sophistication of cyber crime incidents

- changing policing methods, including the increasing use of artificial intelligence, number plate recognition, and drones in policing

- changes in operations and services because of legislative and machinery of government changes or business improvements, such as the implementation of recommendations from inquiries and reviews.

These drivers often result in increased demand or reprioritised police officer deployment. They can affect the availability of the police workforce for day-to-day operations. They can also mean QPS has to establish special teams and provide training and skills development.

For example, implementing the important organisational and cultural changes arising from various reviews will probably mean QPS has fewer staff to meet other current demands.

The Queensland Police Service undertakes limited forecasting and modelling of demand

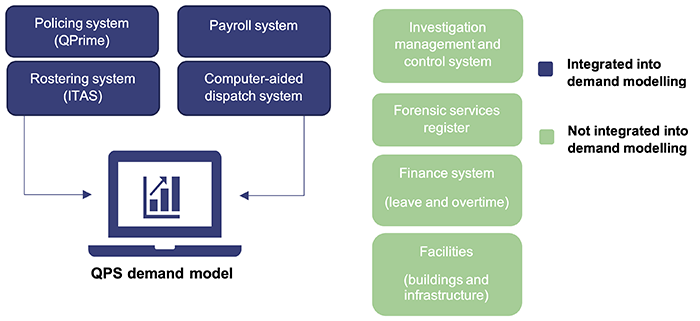

In August 2019 QPS, in partnership with the Queensland Treasury Corporation, developed a demand model specifically focused on frontline policing demand. The model draws data from key systems to provide analytics on actual demand and to better understand the volume and types of demand facing QPS frontline services. QPS uses the demand model to help provide evidence for requests for police and staff resources. As a by-product of the demand model, it has a series of demand dashboards that provide information to assess current state workload demand.

However, the model is based only on historical demand. It does not provide any predictive analysis regarding future demand. Also, it does not cover the full range of services QPS provides, which means the organisation is attempting to plan for future demand with only part of the picture and data.

QPS does not undertake statewide forecasting and does not have a comprehensive picture of its changing and emerging demand. Some regions and districts do forecast and plan demand, but QPS does not have an overall, evidence-based understanding of demand or of how it may change in the future. The existing demand model could form the basis of future forecasting and modelling, but QPS needs to expand the data sets it currently uses.

In addressing this shortfall, QPS is enhancing its data analytics capability and capacity. QPS has advised it will use this capability to develop a comprehensive suite of workforce analytics. It is also working with external experts to develop modelling capability and specific demand models using additional data.

For example, the recently developed domestic and family violence (DFV) demand model provides a perspective on the DFV demand met by the QPS workforce at a point in time using historical data and trends, activity analysis, and available resources. The purpose of the model is to measure and forecast demand for DFV to provide QPS with an understanding on future workforce requirements and associated costs. QPS advised that it will also assist with identifying areas that require further development and opportunities for change.

The Queensland Police Service does not have a clear picture of total demand on services or supporting activities

While QPS measures time spent responding to calls for police assistance (referred to internally by QPS as calls for service), it does not have a clear picture of how officers spend all their time during shifts. For example, it records limited information on the time police officers spend on proactive policing, and it does not measure the time spent on filing incident reports and internally generated work.

The demand model uses statistical and population information and compares historical data on volumes and types of crime. Types of crime are broken down into 12 themes such as personal offences, property offences, traffic, and mental health. But the model only uses information that is captured on core, centralised systems – mainly from reported incidents and calls for police assistance. Some systems are not integrated with the demand model. This means the model cannot access some information, such as leave and overtime, when forecasting demand.

Figure 4A shows that only 4 out of 8 relevant systems feed into its demand model.

Queensland Audit Office, using information provided by the Queensland Police Service.

QPS uses information from the systems not integrated with the demand model for other resource planning purposes. This includes using the forensic services register to support submissions to its Workforce Allocation Sub-Committee and using facilities information to assess infrastructure needs.

Other gaps in information that would help develop a clearer picture of demand for police services include:

- data about filing incident reports and other administrative tasks, proactive policing, or the workloads of non-frontline specialist units or staff members. This is because QPS does not measure time spent on these activities

- information about new residential and commercial developments or demographics and socio‑economic factors, to forecast how demand might change in future

- information on national and international trends in crime and policing, which is available to QPS through its participation in inter-jurisdictional groups.

Using data it already holds in its systems, QPS could use predictive analytics to model future trends. This could include techniques such as machine learning (teaching computers to learn from examples of data and patterns and make predictions) and data mining (analysing large sets of data to discover meaningful patterns, relationships, and trends). It has started to use predictive analytics in some units, but it has not planned to roll this out more broadly.

A planned, coordinated, and data-driven approach to forecasting would provide QPS with greater insights into demand. These could then be used to inform decision-making about resourcing and about deploying officers.

|

Recommendation 1 We recommend that the Queensland Police Service develops a robust model for forecasting demand across the service that:

|

Ensuring the workforce can meet demand

QPS has a strategic workforce plan that includes business-as-usual actions but lacks clear goals and strategies to address its recruitment challenges and grow its workforce. The plan contains high-level information about the changing policing environment.

QPS needs to take a pragmatic and strategic approach to growing, optimising, and upskilling its workforce if it is to meet future demand. This includes how it determines the number of police it needs, considering:

- attrition rates

- an ageing workforce

- the current mix of police officers and staff members

- potential gaps in skills and capabilities.

The Queensland Police Service needs to improve how it allocates workforce resources based on demand

QPS’s current governance approach to decision-making on workforce resourcing and allocation includes the:

- Demand and Capability Committee (DCC) – responsible for making resourcing decisions based on available finances. Its role is to prioritise the allocation of resources (funding, people, assets, and information and communication technology – ICT) to meet current and projected demand, and identify and resolve any relevant emerging issues and trends

- Workforce Allocation Sub-Committee of the DCC – responsible for allocating or redistributing positions with a whole-of-service focus. It also considers and (where appropriate) approves submissions for increased resources.

QPS allocates workforce resources to police commands and stations, partly on the basis of historical demand. Stations or commands that need additional resources due to increased workload make a submission to the Workforce Allocation Sub-Committee. The submission considers demand, capability, resources, and risk. The station or command must use the QPS demand model to quantify the need for resources.

The DCC has not focused on forecasting or planning for future demand, which falls within its scope. Nor has it been proactive in requiring its sub-committee or business units to plan for projected changes in demand and capability. These are important considerations if QPS is to continually meet demand as changes occur in its policing environment – including the types and nature of crimes, and ways of working.

We have already noted limitations with QPS’s demand model. We also found that QPS has not used the model consistently across the organisation to analyse patterns and trends in calls for service (via 000 and other methods) over time and to adjust its resourcing accordingly.

The current workforce growth target is not based on analysis of demand and skills

The police service consists of police officers, police recruits, and staff members. In July 2020, QPS set a target to increase its workforce by 2,025, including 1,450 police officers, by the year 2025. While QPS stated the additional resources were needed to address current and future demand, it did not draw the figures from an evidence-based analysis of future workforce needs. Instead, they were from a Queensland Government 2020 election commitment. QPS acknowledges this.

The government figures and commitment included the allocation of 150 additional police officers per region, with additional positions for discretionary placement. QPS allocates the additional resources through submissions made to the Workforce Allocation Sub‑Committee.

Prior to the election commitment, the growth target was based on population growth across the regions. Neither of these growth targets is based on a robust analysis of demand – which should allocate the right number of police in the right places. Nor are they based on the types of skills that will be needed in the future.

The Queensland Police Service is not meeting its police officer recruitment targets

Attracting, retaining, and recruiting QPS’s police officer workforce is a challenge. Factors driving this include:

- higher-than-forecast attrition rates (for example through its ageing workforce and an increase in resignations)

- a change in society’s perceptions of policing as a career

- a recent shortage of resources in the labour market.

In the 2022–23 financial year, the number of police officers declined by 202. While 483 new police officers were sworn in, 685 left the service. The rate at which police officers left their employment with QPS in 2022–23 increased to 5.6 per cent – a 47 per cent increase from the previous year. However, QPS advised that the police officer attrition rate dropped to 5.1 per cent in the first quarter of 2023–24 and it anticipates further reductions.

To address these challenges, QPS has recently implemented several initiatives to deliver on its growth target. These include running ongoing advertising campaigns across multiple digital channels, lowering the age to apply as a recruit (to 17), offering financial incentives such as relocation payments and assistance with study costs, and developing strategies for attracting international police. QPS is already seeing positive changes to the recruitment pipeline resulting from these initiatives. QPS advised there are currently 587 recruits in training in Brisbane and Townsville academies. However, meeting its growth target is reliant on effective recruitment outcomes and the successful completion of training by recruits to become sworn officers.

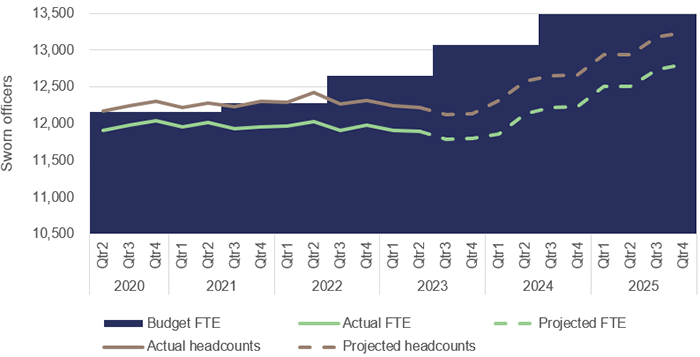

Figure 4B shows the sworn police officer growth against the government’s target (shown as Budget FTE). This includes:

- actual full-time equivalent (FTE) and head count for 2020–21 to 2022–23

- QPS projections of the FTE and head count it is likely to achieve from 2023–24 to 2024–25.

The projections are based on recent changes to the recruitment pipeline. The figures show a sworn police officer shortfall of 678 FTEs by the end of 2025.

Note: Qtr – quarter.

Queensland Audit Office, using data provided by the Queensland Police Service.

The Queensland Police Service needs to plan for its ageing workforce

Queensland has a mandatory retirement age of 60 years for sworn police officers. This is a legislative requirement under the Police Service Administration Act 1990 for officers who do not hold a position under a contract. There are no plans to change this. No other state has a mandatory retirement age except for Tasmania, which has a retirement age of 65 years.

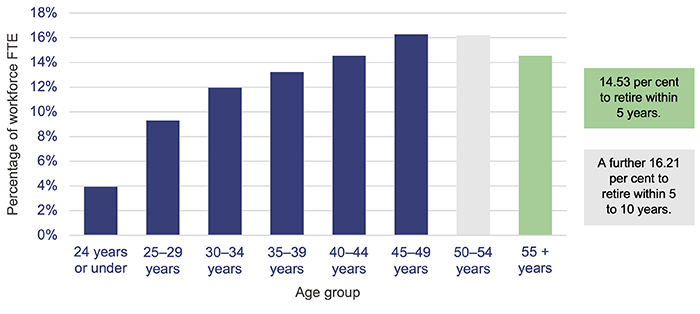

Over the next 10 years, 30.74 per cent of the QPS’s current workforce is due to retire, as shown in Figure 4C.

Queensland Audit Office, using data provided by the Queensland Police Service.

While police officers are required to retire at 60 years, they can apply to return as a staff member or a special constable. QPS advised that in 2021–22, 212 police officers retired. Only 8 returned to the organisation in an unsworn capacity.

In April 2023, QPS announced that it would use retired officers to serve as special constables when a surge in capacity is needed, for example, in the case of natural disasters or major events. While this initiative will support the QPS’s ability to meet a surge in demand, recent numbers of returning officers are low, so this will not address the overall shortages in its workforce.

QPS needs to develop a broader, statewide program to encourage and support retiring officers wishing to return to the service as either as a special constable or as a staff member. This includes identifying suitable roles for them to take on.

The Queensland Police Service needs to identify the best mix of police officers and staff members

QPS has approximately 3,800 staff members throughout its organisation, and they play an important role in supporting policing functions. They undertake tasks such as vehicle and equipment maintenance, fingerprint analysis, intelligence analysis, administration, and training – freeing up sworn officers to focus on frontline services.

Since 2016, the mix of police officers and staff members had remained consistent at an average ratio of 80:20 (police officers : staff members).

To manage the increasing demand for police officers, QPS needs to consider whether its mix of police officers and staff members is optimal. It has started several initiatives aimed at rebalancing this workforce mix, including:

- merging some central commands, for example, the Intelligence and Covert Command and State Crime Command, with some roles transitioning from sworn to unsworn positions

- setting a target to appoint 575 staff members in 2022–23 to assist with specific functions currently undertaken by police officers – such as watchhouses and prosecutions

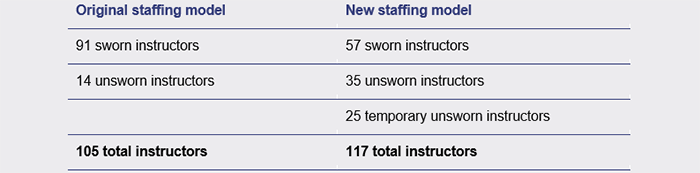

- restructuring one training centre to free up police officers, as explained in Figure 4D: Case study 1.

|

Bob Atkinson Operational Capabilities Centre |

|---|

|

In 2020, QPS restructured the staffing model of one of its training centres – the Bob Atkinson Operational Capabilities Centre. It identified sworn instructor roles that could be performed by staff members. By September 2022, the staffing model at the training centre had a larger civilian workforce as follows: Applicants for the positions were of high calibre and included international police and military members, elite athlete strength and conditioning coaches, and paramedic instructors. This initiative proved to be successful in:

Surveys of participants showed a high satisfaction with the quality and delivery of training – 90 per cent for existing officers and nearly 100 per cent for recruits. As a result of the learnings from this initiative, QPS is considering a new proposal for an additional 8 staff members for this centre. |

Queensland Audit Office, from information provided by the Queensland Police Service.

While these are positive steps, QPS does not have a central or coordinated approach to designing the best mix of sworn police and staff members, police liaison officers, and protective security officers across the organisation. It has not taken steps to review all positions or tasks that do not require police powers.

As described in Chapter 5 of this report, QPS mostly rosters administrative and support staff during standard business hours, which often does not align with peaks in calls for service. In considering the optimal mix of sworn and staff members, it needs to consider how it can best use this workforce to support frontline officers.

In March 2022, the Queensland Treasury Corporation found that police officers were paid 38 per cent more than staff members. A high proportion (52 per cent) of staff members are at the lower end of the administration officer pay level of government (A03 level) and approximately one-third (39 per cent) of them fill positions in the districts. This represents a cost-effective opportunity to free up police officers by allowing staff members to do more administrative tasks.

The Queensland Police Service needs to understand its future skills and capabilities

QPS’s police officers and staff members must have the necessary skills and capabilities to meet changing and emerging demand. When analysing its workforce, QPS considers the profile, but has not developed a clear picture or vision of the skills and capabilities it needs across the state to meet future demand.

QPS participates in a national cross-jurisdictional research group. As part of environmental scanning, this group has collated information about what the future policing workforce could look like. But QPS does not include this information in the environmental scanning document it circulates internally for discussion or action.

The cross-jurisdictional research group also identified that additional skills will be needed in the future to support technological advances and the related changes in service delivery models. QPS has not undertaken an organisational review to determine the types of skills and capabilities it will need for frontline police to meet demand in the next 5 to 10 years.

Having adequate equipment and infrastructure

To be effective and to keep officers safe, today’s police need contemporary equipment and technology. QPS uses operational equipment ranging from body-worn cameras, tablets, and video recorders to higher-value assets such as vehicles, aircraft, and marine vessels. Today’s police also need suitable infrastructure, which includes the buildings they use centrally and in the districts.

QPS currently has enough operational equipment for its officers. None of the staff we interviewed in 4 districts and 5 stations raised concerns about the availability of equipment needed to do their job.

However, QPS lacks a statewide picture of its forecasted asset needs, and it has not progressively maintained its existing infrastructure. It needs to identify future requirements for equipment and fit‑for‑purpose buildings.

The Queensland Police Service needs to align its asset planning with workforce growth

QPS has a 5-year replacement cycle for its fleet of vehicles, but it does not have a life cycle replacement plan for other types of assets needed to support frontline officers in meeting future demand. This includes operational equipment for policing such as body-worn cameras, vests, and tasers.

QPS has a significant infrastructure asset base, but the condition of some of its buildings is deteriorating, leading to poor working conditions for staff. It is developing a new regional asset management plan for the next 10 years, but it has not progressively maintained its existing infrastructure. The current costs to rectify defects exceed $39.5 million.

In addition, QPS has estimated $93.6 million is needed to address the backlog of maintenance. We acknowledge that some of these responsibilities only recently returned to QPS following machinery of government changes.

In an infrastructure review, QPS assessed 8 out of 15 districts. It identified that the infrastructure in some districts was not fit for purpose and will not be able to accommodate growth in staff. While it has identified the opportunity to close some stations, it advised us that it is reluctant to do this, especially in regional areas where the police station is the only government building.

QPS stopped the review because of limitations it identified. It is currently developing a forward capital program to:

- facilitate accommodation of frontline staffing growth to meet expected demand

- refurbish/replace facilities

- prioritise initiatives to support service delivery changes.

The Queensland Police Service uses technology to support frontline policing, but it has not evaluated its benefits

Technology has always been an integral component of policing, and includes telecommunications, cameras (red light cameras and speed cameras), social media, and data analytics. Using technology effectively has the potential to improve operating efficiencies.

Figure 4E shows examples of where QPS is using technology in frontline policing to gain efficiencies.

|

|

Frontline officers use QLiTE tablets and mobile applications to access real-time information while on the move. This allows them to respond promptly to incidents. In some cases, officers complete paperwork onsite and issue infringement notices electronically. |

|

|

Community members can use online reporting and electronic evidence management systems to report non-urgent incidents and crimes. They can upload digital evidence such as CCTV footage and photographs relating to issues like dangerous driving, traffic crashes, and retail theft. This technology reduces the need for officers to physically attend non-urgent incidents, allowing them to use their time and resources more effectively. |

|

Live-streaming body-worn cameras |

Frontline officers use body-worn cameras to enhance transparency, accountability, and evidence gathering. The evidence can be used in court proceedings, which reduces the need to obtain written statements from victims. Other benefits include the ability to live-stream policing activities. This was demonstrated during a siege on Magnetic Island in 2022. It enabled a police negotiation coordinator to manage on-scene negotiators without needing to travel to the island. |

Queensland Audit Office, using information provided by the Queensland Police Service.

QPS relies significantly on technology to deliver frontline services. However, it has not analysed the benefits or efficiency savings from using these technologies. Neither has it evaluated which technologies it should invest in to improve its ability to meet demand. For example, it has not assessed whether there are benefits in further developing QLiTE by adding offline functionality.

This is because QPS does not have a broader program for continuously researching and investing in technologies that provide the most benefit for frontline operations.

It has developed digital, data, and ICT strategies and is currently working on a 10-year technology road map, which it will be submitting for the Queensland Cabinet’s consideration. While these are first steps in enhancing its use of technology, they are high-level documents only. QPS needs to develop them into actions and/or projects with a corresponding investment plan.

|

Recommendation 2 We recommend that the Queensland Police Service improves its strategic workforce planning, including:

|

5. Meeting the current demand for services

This chapter is about how QPS deploys its workforce to meet the current demand for its frontline services. We were only able to examine how QPS responds to and meets initial calls for police assistance (through 000 and other sources). While QPS gathers data on offences, it records limited information on the time spent by police officers on proactive policing and follow-up investigations.

We look at how QPS responds to calls for police assistance, and whether it is meeting its performance standards. We also examined what QPS has done to address issues affecting its ability to meet demand, including a major change approach – the Service Alignment Program.

The Service Alignment Program

QPS is facing significant challenges in maintaining the level of resources needed to meet demand. In January 2020, it established a major transformation program – the Service Alignment Program. This was in response to a 2019 strategic review set up to identify systemic issues affecting its ability to meet demand.

This program included about 40 individual projects aimed at streamlining business processes and optimising service delivery. In July 2021, QPS closed the program and transitioned individual projects to business as usual. It stated that one of the benefits of closing the program was that 184 positions were re-allocated – 155 of them to priority areas (frontline and/or frontline support).

Work on a frontline service delivery model continued as a separate project until that was also closed, in May 2023. During that time, the model was piloted in Moreton district and then rolled out in Logan. Despite seeing positive results from the pilot and rollout, some processes, such as rostering, reverted to how they were prior to the project. The total QPS spent on the service delivery model between the 2019–20 and 2022–23 financial years was $25.9 million. Outcomes from the pilot and rollout at Logan were intended to inform a statewide rollout strategy for the new service delivery model, originally expected to be in all districts by 2024.

QPS stated that implementing the new model, together with the high number of recommendations from recent inquiries and reviews, was resulting in both change and workforce fatigue. The Commissioner has not identified how, in the absence of this program, QPS will enhance its service delivery.

Figure 5A: Case study 2 describes the service delivery model piloted at Moreton and trialled at Logan and the initial benefits it achieved.

|

Trial of new frontline service delivery model |

|---|

|

QPS designed and tested a new service delivery model for frontline services. The model went live in the Moreton district in February 2021. QPS chose this district as a pilot location to test, learn, and build capability prior to implementing the model across the state. QPS considered emerging issues and learnings during the pilot project, making changes to its approach to managing change and workforce planning. The delivery model implemented at Moreton included:

Trial results QPS reported that the trial at Moreton delivered positive results. These included:

Following the implementation in Moreton, the model was rolled out across the Logan district with similar results. External review Because of staff concerns, QPS commissioned an external review of the project. This review highlighted benefits of the model and also made recommendations to improve the likelihood of further success of the project. Benefits identified in the external review included:

|

Queensland Audit Office, from information provided by the Queensland Police Service.

Responding to calls for service

In Chapter 4, we noted that while QPS measures time spent responding to calls for service, it records limited information on the time spent by police officers on proactive policing and follow-up investigations. We were therefore unable to assess how effectively QPS manages demand other than initial calls for service.

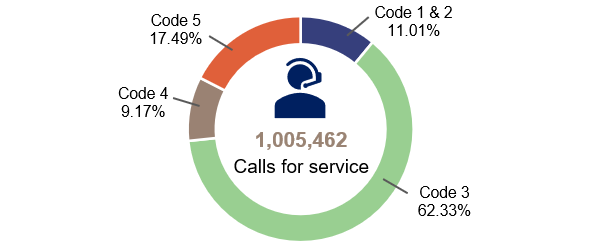

Current demand for policing comes from various sources, such as calls for assistance (referred to by QPS as calls for service) from the public and through government directives (for example, policing events, and border closures and hotel quarantine, such as during COVID-19). Each can have differing levels of urgency (based on safety versus good order) and resourcing implications. In 2021–22, QPS received 1,005,462 calls for service, which came from:

- phone calls through 000 – the national number dialled for emergency assistance for police, ambulance, or fire (79 per cent)

- phone calls or online reporting through Policelink – a method to contact police for all non-urgent matters (6 per cent)

- phone calls or other forms of request for police assistance from government agencies such as Queensland Health (15 per cent).

The community makes most of the calls for police assistance. These can be for minor problems such as loud neighbours, or for more serious crimes like domestic and family violence, burglaries, and homicides.

For this reason, QPS prioritises calls for service by assessing the urgency and level of perceived threat to personal safety. Not all calls for service require police attendance. QPS uses a framework to make the assessment and allocates a code from 1 (very urgent) to 5 (does not require a police tasking). It implemented this framework statewide in February 2021.

Code 1 – very urgent – for circumstances of imminent danger to human life or where life is ‘actually and directly threatened’ with imminent danger.

Code 2 – urgent – for circumstances similar to Code 1 but when danger or threat to human life is not imminent. Code 2 calls include circumstances involving injury, or a present threat of injury, to a person or property.

Code 3 – requires a direct police response to an incident that is occurring and/or may escalate.

Code 4 – may be resolved by alternate resolution, which, according to the QPS operational procedures manual, consists of resolving the matter over the phone or making an appointment with the caller.

Code 5 – does not require a police tasking.

Source: Queensland Police Service Operational Procedures Manual, Chapter 14, sections 14.24.1 and 14.24.2.

Figure 5B shows a breakdown of calls for service received by QPS in 2021–22 from all sources, by code.

Queensland Audit Office, using data provided by the Queensland Police Service.

Demand for service is growing faster than officer numbers

Since 2016, the demand for service has increased by 30 per cent, while the average police officer head count has increased by 25 per cent over the same period.

This, combined with the increased complexity of the different crime types and social issues police deal with, makes QPS's job harder, particularly since complex incidents generally require more police time.

In 2021 and 2022, the top 4 incident types QPS received were disturbances and disputes, noise complaints, domestic violence, and welfare checks. In this time:

- Domestic and family violence incidents increased 14 per cent from 79,909 to 91,094.

- Mental health incidents increased 13 per cent from 10,562 to 11,902.

Most Code 1 and 2 calls come through 000

In 2021–22, QPS received 131,556 Code 1 and 2 calls. Figure 5C shows a breakdown of the sources through which they were received.

Note: The ‘other government agencies’ category includes Crime Stoppers.

Queensland Audit Office, using data provided by the Queensland Police Service.

The average time to dispatch a response team for each of these sources of Code 1 and 2 calls during 2021–22 was:

- 000 calls – 3 minutes and 32 seconds

- other government agencies – 7 minutes and 35 seconds

- Policelink – 11 minutes and 5 seconds.

Clearly, the average time taken to dispatch a response team was higher for calls received from sources other than 000. This is mainly due to calls being generated in different systems. Calls coming through systems other than 000 require additional work before they can be transferred to the dispatch system for action. This process delay is affecting QPS’s ability to attend some high-priority and potentially life‑threatening calls in an efficient and timely manner.

Methods other than 000 are not designed for high-priority or emergency incidents. In September 2021, QPS launched a public media campaign aimed at reducing non-urgent calls to Triple Zero (000). However, given the number of high-priority calls coming through these other sources (around 7,900 in 2021–22 through Policelink), QPS needs to regularly educate external parties on the correct communication channels.

The Queensland Police Service attends to most of its calls for assistance, but it does not meet its target response times

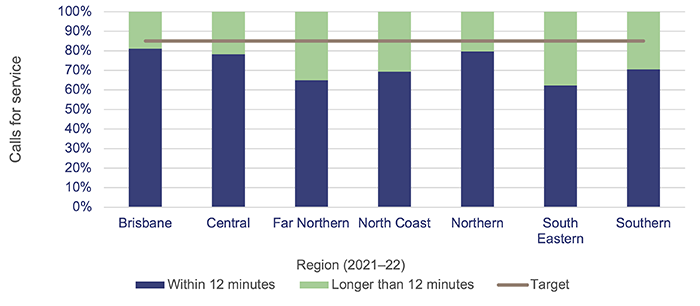

QPS reports its performance annually through its service delivery statements (SDS – which provide budgeted financial and non-financial information for a government portfolio each year). In 2021–22, QPS reported that it attended 85.3 per cent of Code 1 and 2 incidents within 12 minutes. This met its target of 85 per cent, which was increased from 80 per cent for the 2022–23 period.

However, QPS had incorrectly calculated the attendance rates of Code 1 and 2 calls and the actual figure was 78.2 per cent. Its internal review processes had not identified this error prior to publishing the SDS. For 2023–24, it has amended the target to 80 per cent.

Also, the QPS’s SDS report for this performance measure only captures incidents attended for calls received through 000. It does not include data on the 21 per cent of Code 1 and 2 calls received in 2021–22 from other sources, such as Policelink and other government agencies. While QPS internal documents note this, it is not stated in the SDS, which may mislead readers. When we included Code 1 and 2 calls from all sources, incidents attended within 12 minutes dropped from 78.2 to 72 per cent.

Figure 5D shows the revised percentage response time for Code 1 and 2 calls received through all sources, by region.

Queensland Audit Office, using data provided by the Queensland Police Service.

The lowest response rates were for the South Eastern and Far Northern regions, with between 62 and 65 per cent of calls attended to within 12 minutes. The response rates within 12 minutes for Brisbane and Northern regions were 80 per cent and 79 per cent respectively. QPS advised that responsiveness varies between regions due to several factors, such as distance, remoteness, and availability of resources.

QPS’s performance target for Codes 1 and 2 – to attend 85 per cent of calls within 12 minutes – is comparable to that of other jurisdictions. Most have set response times for Code 1 and 2 calls within the range of 10 to 15 minutes, and most have a target of 80 per cent. (Appendix D has further details on other jurisdictions’ targets and performance.)

Using performance information to improve service delivery

Performance information is a tool for service management and improvement. It supports informed decision making and is an early warning system that enables managers to take preventative action.

By setting a performance target for Code 1 and 2 calls, QPS can demonstrate whether it attends them within reasonable time frames. Performance targets also assist in planning for and deploying resources – including staff and equipment – more effectively.

Only 2 Australian jurisdictions have set externally reported performance targets for Code 3 calls. Western Australia has a one-hour response target for Code 3 calls (within the Perth metropolitan area), and the Australian Capital Territory has a response target of 48 hours. No jurisdictions measure performance for Code 4 calls.

In 2021–22, QPS responded to 60 per cent of Code 3 calls within one hour. It does not report publicly on this, but it also has not analysed the data to assess if this is an acceptable level of performance. Analysing performance information gives insights into service delivery and helps assess trends or anomalies and identify potential quality issues. QPS could make better use of its performance information to understand and improve its practices.

Unattended calls

While QPS responded to nearly 90 per cent of calls requiring a police response (Codes 1 to 4) in 2021–22, it recorded that it did not respond to over 86,594 calls. These included:

- 369 (less than 0.5 per cent) of Code 1 and 2 calls (very urgent and urgent)

- 10 per cent of Code 3 calls

- 24 per cent of Code 4 calls.

Calls for service categorised as Code 5 do not require police attendance. In 2021, many incidents previously categorised as Code 3 were re-categorised to Code 5, to ensure QPS was responding to calls for service of higher urgency and level of perceived threat to personal safety. However, QPS was unable to provide us with further information to support the reason for the change. It was also unable to tell us whether it has examined the impact to determine if it was appropriate.

While our analysis of a sample of unattended Code 1 and 2 calls found reasonable explanations for most (such as calls being downgraded to a lower priority, or duplicate calls), QPS advised that it did not regularly analyse this information to identify issues or areas for improvement.

As a result of our initial finding, QPS reviewed all unattended calls (Codes 1 to 3) from July 2021 to April 2023. It identified that most calls were dealt with appropriately but were either not finalised correctly in the system or were determined not to require a police attendance. In some instances, jobs were a duplicate.

Figure 5E shows a breakdown of reasons QPS provided from its analysis for the 369 Code 1 and 2 calls originally recorded as not attended in 2021–22. The 2 main reasons were that:

- calls were attended by another government agency (31.7 per cent) – for example, in cases of attempted/threatened suicide

- police attended, but the call was not ‘closed’ in the system (25.5 per cent).

|

Non-attendance reason recorded |

Number |

Percentage |

|---|---|---|

|

Police attended (but attendance was not recorded) |

94 |

25.5 |

|

Change in circumstance |

73 |

19.8 |

|

Other government agency attended – police not required |

117 |

31.7 |

|

False alarm (police not required, including hoax calls) |

60 |

16.3 |

|

Decision not to attend |

12 |

3.3 |

|

Unable to determine reason |

9 |

2.4 |

|

No crews available |

3 |

0.8 |

|

Total |

369 |

100% |

Queensland Audit Office, using data provided by the Queensland Police Service.

|

Recommendation 3 We recommend that the Queensland Police Service improves its response to demand for service by:

Recommendation 4 We recommend that the Queensland Police Service improves the usefulness and transparency of its public performance reporting on responding to calls for service by:

|

Rostering staff to meet demand

QPS uses a rostering system to manage its frontline workforce. There are 7 regions across the state, split into 15 districts and 341 stations. QPS does its rostering at the station level, where officers are scheduled for various shifts and duties. Officers are typically rostered for a combination of day, evening, and night shifts, with rest days scheduled between blocks of shifts. Effective rostering is critical to ensuring there are enough frontline officers available to meet demand as it arises.

Rostering practices are inconsistent, and they limit resource-sharing

QPS has inconsistent practices when rostering staff to meet demand, and not all rostering clerks have received formal training on how to use the rostering system. Some stations are not using the QPS demand dashboard (see Chapter 4) to help identify peak periods of demand.

Rostering is done based on head count, but because the rostering system is not integrated with the HR and payroll system it does not consider the availability of staff to be rostered for service when allocating them to shifts. For instance, after annual leave, sick leave, scheduled days off, and training are considered, there may not be enough police officers available in a given week to provide the required level of coverage.

Because rosters are organised at the station level, it is difficult to share resources across regions and districts to effectively cover all shifts and meet peak demand.

Rostering is not optimised to match peak calls for service

Current issues with QPS’s rostering system mean its rostering practices have not been optimised to ensure it has enough resources to match peak calls for service. Our analysis of data from QPS’s computer-aided dispatch (QCAD) system and the rostering system indicates that QPS is not rostering police officers on duty in line with calls for service.

Current issues include limited demand data, and a lack of integration with other corporate systems, such as the payroll system. Police officers on duty during the week deal with more than responding to calls for service, such as attending court and incident management. Whereas at the weekends, police officers mainly focus on responding to calls for service. In the absence of supporting data, it is difficult to assess whether the allocation of police officers across the week is sufficient to meet calls for service.

The greatest number of calls for service occur between 5:00 pm and 11:00 pm, with a further increase at weekends. When demand exceeds available resources, frontline officers typically spend less time at incidents. QPS has not analysed whether the quality of service is impacted when calls for service are not matched by the number of officers on duty.

Administrative and support staff generally work standard business hours, which often do not align with the peaks in demand. This may result in frontline officers needing to perform administrative and operational tasks, such as manning front counters and fingerprinting, during these peak periods. This takes them away from frontline duties and creates further pressure to meet demands for service. It also has a budgetary impact. A review by the Queensland Treasury Corporation in March 2022 found police officers are, on average, remunerated at a rate 38 per cent higher than other staff members.

A roster review project is underway

In early 2023, QPS established the Rostering Review Steering Committee to investigate, analyse, and address a range of issues identified around rostering practices across QPS. Using project working groups, QPS aims to improve its understanding of the complexity of QPS demand and current QPS rostering systems. Its objective is to then identify and implement strategies to improve operational rostering. The project scope includes enhancing QPS rostering capability and resources and reviewing data limitations. The expected completion date for the project is June 2026.

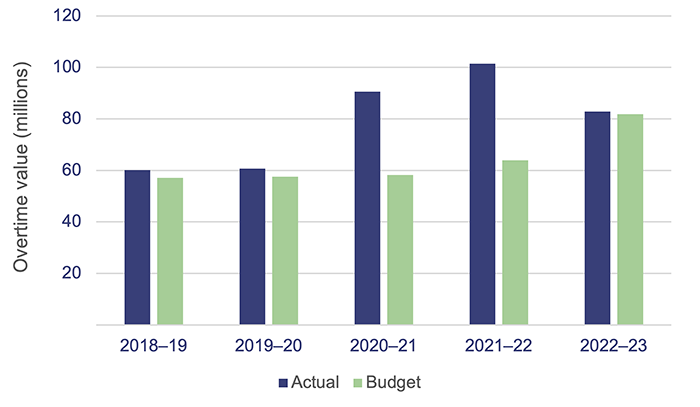

Overtime has significantly increased for police officers

Not rostering to meet peak calls for service, combined with a lack of resources, can result in officers needing to work beyond their regular shift hours to meet demand. This has contributed to a 38 per cent increase in QPS overtime over the last 4 years – from $60.1 million in 2018–19 to $82.8 in 2022–23 – as shown in Figure 5F.

Queensland Audit Office, using finance system data provided by the Queensland Police Service.

The significant increase in actual overtime in 2021 and 2022 was likely affected by additional duties supporting the government response to COVID-19. We note other factors also contribute to the increased overtime, such as running specific campaigns. Analysing patterns and reasons for overtime will inform workforce planning.

|

Recommendation 5 We recommend that the Queensland Police Service continues to develop consistent rostering practices to improve how it deploys available resources across the state. This should include:

|