Overview

Queensland's growing and ageing population is increasing demand pressures on the public health system in a time of significant fiscal constraints. As a result, some patients wait longer than they should for a specialist outpatient appointment. This has been exacerbated over the last 18 months with COVID-19 placing further strain on the health system.

Since July 2015, the Queensland Government has invested $595 million in its Specialist Outpatient Strategy to address specialist outpatient long waits and known difficulties for people and GPs trying to get the right specialist service at the right time.

Tabled 6 December 2021.

Report on a page

Queensland's growing and ageing population, with associated increasing prevalence of chronic diseases, is increasing demand pressures on the public health system in a time of significant fiscal constraints. As a result, some patients wait longer than they should for a specialist outpatient appointment. This has been exacerbated over the last 18 months with COVID-19 placing further strain on the health system.

Since July 2015, the Queensland Government has invested $595 million in its Specialist Outpatient Strategy to address specialist outpatient long waits and known difficulties experienced by people and their general practitioners (GPs) trying to get the right specialist service at the right time. A long wait is where patients wait longer than clinically recommended for a specialist appointment.

In this audit we examined whether, by implementing the Specialist Outpatient Strategy, the Department of Health and the hospital and health services (HHSs) (collectively referred to as Queensland Health) have improved patient access to specialist outpatient services and reduced waiting lists.

Demand for services is exceeding supply

Almost 80 per cent of the Specialist Outpatient Strategy funding was used for additional specialist outpatient appointments to reduce long waits. Queensland Health halved long waits in the first three years but increasing demand means the number of long waits for non-urgent cases has increased steadily since 2017. Queensland Health needs to address the challenge of increasing demand in its further reform work to create sustainable improvement.

Alternate models of care improve access for patients

Alternate models of care have increased the capacity of the public health system and provided more timely access to services for some patients. These models have reduced waiting lists in some specialties, but they need to be used more broadly to significantly increase capacity and optimise benefits. Specialist telehealth has improved patient-centred care through local access to some specialised services.

New systems are more efficient, but more GP engagement is needed

New contemporary information management systems have improved system integration, created process efficiencies for hospitals and GPs, and improved referral quality. They have improved the management and tracking of patient referrals along all stages of the healthcare journey.

However, GP uptake of electronic (smart) referrals is low, which reduces effectiveness. Greater engagement and support are needed to onboard more GPs.

Our recommendations

We made four recommendations to help Queensland Health address pressure points in the health system by changing how hospitals triage non-urgent cases and embedding proven models of care and effective practice across the state.

1. Audit conclusions

By implementing the Specialist Outpatient Strategy, Queensland Health has improved patient access to specialist outpatient services and addressed the backlog of long waits at a point in time. However, despite Queensland’s health system treating more patients through specialist outpatient services, demand for public health services continues to increase and exceed supply. Urgent cases are mostly seen within clinically recommended times. But challenges remain, with non-urgent cases being seen outside clinically recommended times and the number of long waits steadily increasing since 2017. Many people still wait longer than the clinically recommended time to see a medical specialist.

Growth in demand is greater than population growth. This is making it more difficult to match supply and demand and actively manage patients to ensure they are on the right pathway at the right time. There is a finite ability to provide services in the public health system due to availability of public specialists. For some specialties, there is a statewide shortage of clinicians, with both the public and private health sectors competing for scarce resources.

COVID-19 has also impacted the supply of specialist outpatient services due to the reallocation of resources to deal with the pandemic, temporary suspension of some clinics, and restrictions on engaging clinicians from interstate and overseas.

While this audit focused on supply management, we note that the increasing demand for services and pressures on supply have made it difficult to sustain improved access and reduce waiting times. More effective demand management strategies for non-urgent cases are needed for sustainable delivery of these services.

Tackling the whole patient journey takes time. The Specialist Outpatient Strategy has laid a foundation to improve patient access and increased system integration by using contemporary information management systems and innovative models of care. More work is needed to embed and build on these improvements across the state and enhance practices to better respond to anticipated future health needs.

Queensland Health has now commenced the next stage of reform—Connecting your Care—to address priority pressure areas in non-admitted care, after some delay due to the public health response to the pandemic. The Connecting your Care initiatives will build on work done under the Specialist Outpatient Strategy to better coordinate care across the system, manage demand and achieve better outcomes for patients. This includes better connecting and enabling other health providers such as nurses, general practitioners, and other community health services. Implementing the initiatives is expected to take 12–18 months. Once implemented, the aim of Connecting your Care is to expand the foundation programs, such as smart referrals and YourQH, while developing innovative centralised digital and decision-making solutions.

The recommendations made in this report should assist in achieving the intended outcomes of this next key reform.

2. Recommendations

We recommend that the Department of Health implements the following recommendations as part of the Connecting your Care initiatives:

|

Addressing pressure points and releasing capacity |

|

|

Completing journey improvement implementation |

|

|

Reference to comments

In accordance with s. 64 of the Auditor-General Act 2009, we provided a copy of this report to the Department of Health. In reaching our conclusions, we considered its views and represented them to the extent we deemed relevant and warranted. Any formal response from the Department of Health is at Appendix A. We sent a copy for their information to each hospital and health service.

3. Managing specialist outpatient waiting lists

This chapter is about how Queensland Health manages specialist outpatient waiting lists and whether additional specialist appointments have improved waiting times.

Specialist outpatient services are a vital interface between acute inpatient and primary care services. Patients need access to medical specialists for diagnostic assessment, screening, treatment, ongoing management, and pre- and post-hospital care.

Since July 2015, the Queensland Government has invested around $595 million in addressing specialist outpatient long waits and patient journey improvements through the Specialist Outpatient Strategy. The government’s initial investment was $361.2 million over four years, commencing July 2015, with further investment since then. The strategy was announced by the Minister for Health in June 2016.

The aim of the Specialist Outpatient Strategy was to:

- boost capacity of the public health system by providing additional specialist appointments and healthcare services

- address known difficulties experienced by people and their general practitioners (GPs) trying to get the right specialist service at the right time by targeting investments in key patient journey improvements.

We look at the impact of innovative models of care in Chapter 4, and contemporary information systems in Chapter 5.

Throughout the report we refer to long waits, ultra-long waits and seen within time.

A long wait is when a patient has waited longer (by one day or more) than the clinically recommended time for a specialist appointment.

Queensland Health also monitors ultra-long waits—where patients have waited more than two years for an initial specialist outpatient appointment from the date they were placed on a specialist outpatient waiting list.

Seen within time is where patients attend their first appointment within clinically recommended times.

Additional specialist appointments and services

Queensland Health allocated $471 million (almost 80 per cent of the total investment in the Specialist Outpatient Strategy) to fund additional specialist outpatient appointments and services. Its short-term goal was to reduce the backlog of long waits, but more specifically, by 30 June 2017 to:

- reduce the number of long wait patients to fewer than 40,000 and achieve zero long waits for ear, nose, and throat appointments

- clear all ultra-long waits (patients waiting more than two years for an initial outpatient appointment).

Queensland Health allocated the additional funding to those HHSs with the greatest number of long waits or those with a demand/capacity imbalance. Further information on how funding was allocated is in Chapter 5.

Specialist outpatient referrals

Under the current referral model, referring practitioners, usually GPs, assess a patient’s condition and need for a specialist outpatient service. The referring practitioner sends a referral to the nearest HHS that provides the required specialist service.

The HHS receives the referral and completes an administrative and clinical review. If the HHS has the right information, it triages the patient referral based on urgency of the condition using clinical prioritisation criteria. Sometimes, the HHS sends the referral back to the GP for more information.

Once accepted, the patient is placed on an outpatient waiting list.

Figure 3A shows the first part of the patient journey for those requiring a specialist outpatient appointment.

Queensland Audit Office from Specialist Outpatient Services Implementation Standard.

Waiting time targets

Queensland’s public hospitals use three urgency categories for specialist outpatient services, each with a target seen within time (see Figure 3B). Queensland Health calculates waiting time from the date a patient is placed on a specialist outpatient waiting list to the date they are first seen by a clinician (referred to as the initial service event), excluding any days the patient was not able to receive care for a clinical or personal reason.

|

Urgency category |

Appointment required within |

Target seen within time |

|---|---|---|

|

Category 1 |

30 calendar days |

83% |

|

Category 2 |

90 calendar days |

69% |

|

Category 3 |

365 calendar days |

84% |

Queensland Audit Office from Specialist Outpatient Services Implementation Standard and Queensland Health service delivery statements.

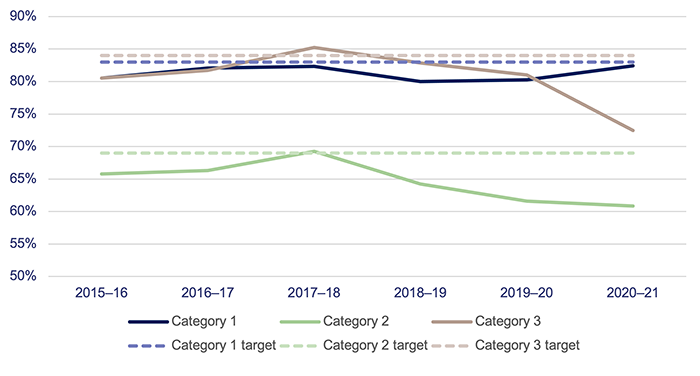

The targets for the percentage of specialist outpatients seen within clinically recommended times have remained the same since 2015–16. Performance results for all categories were publicly reported in Queensland Health’s service delivery statements until 2019–20. In 2020–21, Queensland Health only reported the target for category 1 (83 per cent) in its service delivery statement. This was due to the impact of the temporary pause in accepting routine referrals between March–May 2020 due to COVID-19.

Unlike hospital emergency department and elective surgery performance, reporting on specialist outpatient services is not part of the Australian Health Performance framework. Only Queensland and South Australia publicly report on specialist outpatient services, although their measures are different.

Is demand exceeding supply?

Funding additional appointments helped to clear the backlog of long waits and reduce the average time people were waiting for an appointment. But challenges remain with seeing non-urgent cases within clinically recommended times. The additional funding provided through the strategy did not address continued growth in demand for services.

The health system receives more referrals than initial specialist appointments delivered

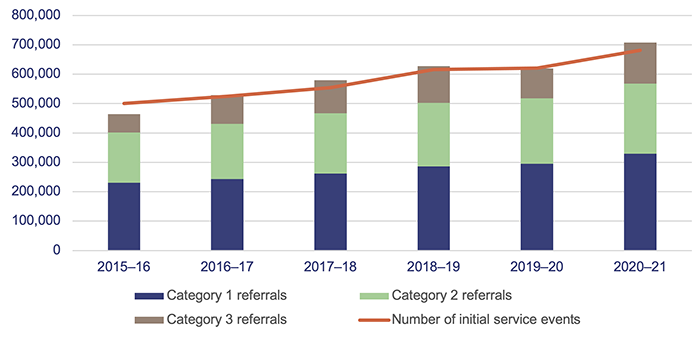

Between 2015–16 and 2020–21, the number of specialist outpatient referrals increased by 53 per cent, while the number of first appointments (termed initial service events) increased by 36 per cent. The increase in referrals exceeded the growth in Queensland’s population, which grew 8.3 per cent between 2015 and 2020.

Figure 3C shows the number of referrals received for specialist outpatient services and initial service events delivered since 2015–16.

Queensland Audit Office from the Queensland Health Specialist Outpatient Data Collection.

The average annual number of referrals over the last six years is 587,844, with just under half the referrals being category 1. For four of the six years, the referrals received exceeded the number of initial appointments delivered, contributing to the growing number of long waits. In 2020–21 there were 25,870 more referrals received than appointments delivered.

At 1 July 2021, there were 230,120 patients waiting for a first appointment, but only eight per cent of these were category 1. This indicates that most urgent cases are seen within time.

Have waiting times for specialist outpatient services improved?

Since 2015–16, Queensland Health has made the following improvements to waiting lists:

- substantially cleared the backlog of ultra-long waits in place in 2015

- met the 2016–17 long wait reduction target to reduce the number of long wait patients to fewer than 40,000

- reduced the number of ear, nose, and throat long waits from 7,617 in 2015–16 to 22 at 30 June 2017

- consistently met or closely met the seen within time targets for category 1 patients.

However, since 2017 the number of long waits has increased. Many patients, mostly non-urgent category 2 and 3 patients, still wait longer than clinically recommended for their first specialist outpatient appointment. The additional funding provided through the strategy did not address continued growth in demand for services.

At 1 July 2021 there were:

- 892 ultra-long waits

- 57,941 long wait patients

- 4,030 ear, nose and throat long wait patients.

In 2020–21, 82 per cent of category 1 specialist outpatients were seen within time, against a target of 83 per cent.

Non-urgent cases are not meeting seen within time targets

Figure 3D shows the percentage of outpatients seen by a specialist within clinically recommended times for each category. Queensland Health consistently met or closely met the target for category 1 patients, but categories 2 and 3 fell below target in the last three years. The sharp decline in category 3 in the last year is mainly due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, with a temporary halt in treating non-urgent cases.

Queensland Audit Office from the Queensland Health Specialist Outpatient Data Collection.

Ultra-long waits have substantially reduced

Figure 3E shows that Queensland Health successfully used the additional funding to substantially reduce ultra-long waits by 30 June 2017. Ultra-long waits continued to decrease until 2019 but have increased again over the last two years. Of the 892 patients waiting more than two years for an appointment as of 1 July 2021, there were nil for category 1, 379 for category 2, and 513 for category 3.

|

Waiting time |

1 July 2015 |

1 July 2016 |

1 July 2017 |

1 July 2018 |

1 July 2019 |

1 July 2020 |

1 July 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2 or more years |

15,802 |

6,640 |

1,159 |

359 |

73 |

1,055 |

892 |

Queensland Audit Office from the Queensland Health Specialist Outpatient Data Collection.

Queensland Health also monitors the number of patients waiting more than four years for an appointment. In 2015 and 2016 there were 3,526 and 994 patients respectively waiting more than four years. In 2017 the number was 27, reducing since then to two or less patients each year.

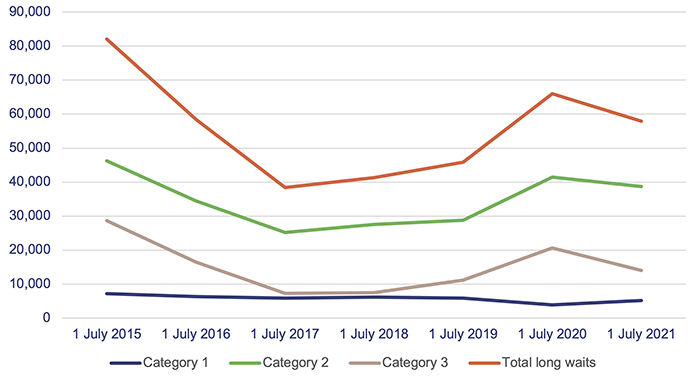

Long waits were halved but are increasing again

Queensland Health advised that when it first started measuring specialist outpatient waiting lists in February 2015 the number of long waits was 104,114. Funding and activity under the Specialist Outpatient Strategy commenced in July 2015. Queensland Health also commenced the statewide Specialist Outpatient Data Collection in July 2015 to provide consistent and actionable service data.

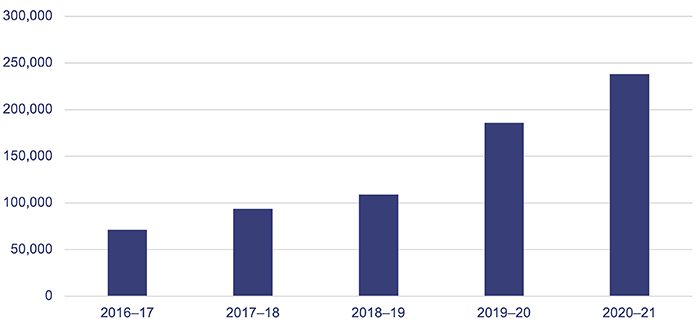

Figure 3F shows that the total number of long waits halved in the first three years of the Specialist Outpatient Strategy. But from 1 July 2017 to 1 July 2020, the total number of patients waiting longer than recommended increased by 72 per cent. There was a 12 per cent decrease in 2020–21, likely due to the impact of the temporary halt in accepting some category 2 and all category 3 referrals from March–May 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Note: Count taken on 30 June each year.

Queensland Audit Office from the Queensland Health Specialist Outpatient Data Collection.

Some clinical specialties have significant and ongoing specialist outpatient waiting lists due to high demand and/or a lack of specialists. Figure 3G shows which specialties had the highest number of long waits on 30 June 2021. These seven specialties, from over 50 specialties, account for 65 per cent of total long waits.

|

Clinical specialty |

Number of long waits |

Percentage of total wait list number |

|---|---|---|

|

Orthopaedic |

9,594 |

17% |

|

Ophthalmology |

7,336 |

13% |

|

Gastroenterology |

6,053 |

11% |

|

Ear, nose, and throat |

4,030 |

7% |

|

Medical other |

3,516 |

6% |

|

General surgery |

3,395 |

6% |

|

Urology |

2,958 |

5% |

Queensland Audit Office from the Queensland Health Specialist Outpatient Data Collection.

Non-urgent referrals could be managed more efficiently

Increasing demand pressures and significant fiscal constraints have led to continuing issues with long waits experienced by category 2 and 3 patients. Further work is needed to match demand and supply differently to ensure patients are on the right healthcare pathway sooner.

Currently, once HHSs categorise patient referrals, they generally manage all referrals in the same way. Typically, HHSs register patients on a waiting list and schedule an appointment within the clinically recommended time frame where possible. Opportunities exist to stream category 2 and 3 patient referrals differently and more proactively, through the continued development and roll out of specialist pathways and different models of care across the state.

In the next stage of reform to address priority pressure areas—Connecting your Care—Queensland Health has identified initiatives to stream referrals at the triage point to optimise access to the right care, drive efficiency, and enhance the quality and safety of patient care.

Specifically, the program will aim to implement:

- centralised referral hubs to improve patient access to the right care sooner, and closer to home

- streamlined access to care through health pathways back to the community

- strengthened relationships with primary care providers by implementing electronic consultations

- timely access to high-quality care through the introduction of care coordination services.

4. Improving access to specialist outpatient services

This chapter is about how well Queensland Health has used new models of care and specialist telehealth to release capacity in the health system and provide more timely access to services for patients.

Traditionally, specialist outpatient care in the public health system has relied on patients first seeing a medical specialist in person. However, with difficulties in supply keeping up with demand, alternate models of care and pathways can positively help to manage demand.

Under the Specialist Outpatient Strategy, around $28 million was used to implement new models of care and pathways, using a broader set of health professionals to contribute to reducing waiting lists and releasing service capacity. About $20 million was used for specialist telehealth services to promote equitable and timely access to care.

Are new models of care increasing the capacity of the health system?

New models of care have increased the capacity of the public health system to provide additional specialist appointments and healthcare services. They have contributed to reducing the waiting lists in some specialties. However, the spread and scale of new models are not yet sufficient to significantly increase capacity and optimise benefits more broadly.

Queensland Health’s New Models of Care Project provided opportunities to trial, establish, and/or enhance alternate models of care involving a broader set of health professionals, such as allied health and nurse practitioners, as a first point of contact in the hospital system for eligible patients. This released clinical capacity to focus on higher acuity cases and improve the patient journey in some HHSs.

In HHSs where alternate care pathways are in place, patients needing specialist care are still appropriately referred to a specialist.

New models of care release service capacity but could be used more widely across the health system

All models of care funded and implemented under the Specialist Outpatient Strategy demonstrated the ability to release service capacity. This means that new patients were initially seen by alternative pathway clinicians, such as allied health and nurse practitioners, providing specialist medical officers with more time to see more clinically urgent patients.

Around 50 of the 61 model of care projects (82 per cent) demonstrated the ability to improve productivity, although some services struggled to measure how this released capacity into improved clinic utilisation.

Queensland Health reported that the New Models of Care Project released service capacity and contributed to reducing the number of Queenslanders waiting longer than clinically recommended for an initial specialist outpatient appointment. At a system level, Queensland Health used overall waiting list performance and long wait reduction to measure effectiveness. However, extra funded appointments also helped reduce long waits.

These proven alternate models of care need to be embedded and used more broadly across the state to release additional effective clinical capacity. Limitations to achieving this include the current funding model and the need for leadership and clinical support.

The following case studies highlight individual models of care and the success they had in releasing capacity and reducing waiting lists. Common challenges facing all these cases are:

- increasing demand that outweighs capacity

- finite ability to provide public services due to the availability of public specialists

- timely access to care

- growing and ageing population

- increasing burden of chronic disease.

Case study 1 (Figure 4A) discusses the Ophthalmology Alternate Pathways Project at the Sunshine Coast HHS.

| Ophthalmology Alternate Pathways Project |

|---|

|

The Ophthalmology Alternate Pathways Project developed and trialled allied health and nurse-led clinics to help manage the ophthalmology patient waiting list within the Sunshine Coast HHS. It included an optometrist-led glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy assessment clinic, an orthoptist-led paediatric assessment clinic, and a clinical nurse consultant-led review clinic. The project ran for one year from January 2018. Aim The project aimed to address challenges facing ophthalmology demand for services by enabling alternate health clinicians to see patients in clinics, supported by documented clinical pathways, to:

Results Queensland Health reported that the three alternate pathway clinics, together with an outsourcing initiative occurring concurrently, released specialist capacity and reduced long waits from 1,031 in January 2018 to five by December 2018. New appointments seen by the alternate pathway clinicians provided specialist medical officers with more time to see more clinically urgent patients. The project resulted in a collaborative multidisciplinary approach to patient care and fostered a positive team environment, which was well received by all involved. The project also identified the need for an interventional clinical nurse consultant to assist in the treatment of patients with intravitreal injections and post-operative cataract care. This provides further support for consultants to meet increasing service demand. These alternate pathways are now embedded as business as usual within the ophthalmology department at Sunshine Coast HHS. |

Queensland Audit Office from Sunshine Coast HHS New Models of Care Project Evaluation.

Case study 2 (Figure 4B) describes how Metro South HHS used specialist nursing and allied health expertise to provide neurology outpatient services.

| Neurology outpatient services |

|---|

|

Metro South HHS used specialist nursing and allied health expertise to provide neurology outpatient services, with neurologist oversight of patient care to ensure patient safety. Services included nurse practitioner-led clinics for multiple sclerosis, epilepsy, and movement disorders; a neurology multidisciplinary outpatient service; and a GP with a special interest in neurology. The project ran from February 2018 to June 2019. Aim The project aimed to increase the proportion of patients seen within clinically recommended times, reduce waiting lists, and identify sustainable solutions to the demand/supply imbalance. Results Queensland Health reported that the project achieved a 61 per cent reduction in the neurology waiting lists and a 74 per cent reduction in patients waiting longer than clinically recommended. The project changed how Metro South HHS delivered its model of care within neurology by:

Metro South HHS has embedded the model in the neurology department, and key nursing and allied health roles have continued with financial support from within the HHS. Metro South HHS is looking to extend the model to further streamline care in the inpatient and outpatient settings. |

Queensland Audit Office from Metro South HHS New Models of Care Project Evaluation—Neurology Initiative.

Non-attendance rates in outpatient clinics can have an adverse impact on patient care, add to the cost of care, and increase waiting list time. Case study 3 (Figure 4C) demonstrates the value of an audit and confirmation collaborative model in decreasing non-attendance rates at Children’s Health Queensland HHS.

| Audit and confirmation collaborative model |

|---|

|

Traditionally, patients who fail to attend appointments are automatically rebooked. This, in part, perpetuates the problem. This audit process cleanses and improves the accuracy of the outpatient waiting list and cancels appointments for patients who will not attend for various reasons (including no longer required, condition resolved, already treated elsewhere, or reschedule required). Attendance patterns show that 60 per cent of patients who are not contactable fail to attend their appointments. The project ran for 18 months from March 2016. At the start of the project, the failure to attend (FTA) rate was 14 per cent. Aim The project aimed to identify true service demand by reducing the FTA rate and long wait numbers. In turn, this would improve patient flow and optimise capacity. Process The audit process at Children’s Health Queensland HHS focused on all long waits, category 2 patients waiting 60 days, and category 3 patients waiting 300 days. The call centre contacted patients/families by SMS and phone to confirm their appointment, with a maximum of eight attempts made. If no response was received, the patient’s contact details were checked, the treating clinician was informed, and the appointment removed. A follow-up letter was sent to the patient and their GP. Results Queensland Health reported that over the period of the project, and in conjunction with other long wait strategies, Children’s Health Queensland HHS:

Children’s Health Queensland HHS has broadly embedded the audit and confirmation processes and their impacts through the use of data reporting tools. |

Queensland Audit Office from Clinical Excellence Division Evaluation Report on Children’s Health Queensland HHS, Centralised Audit and Health Contact Centre Collaboration.

Are specialist telehealth services improving access?

Specialist telehealth services provide easier and more equitable access to patients who experience difficulties accessing services because of location or other challenges. Telehealth services provide safe, cost-effective care closer to home, to improve the health of patients. Benefits include reducing travel time, costs, and inconvenience—for individuals, carers, and health service providers. Telehealth services also improve access to peer support and professional development for the rural and remote workforce and reduce clinical isolation.

Queensland Health identified clinical specialties amenable to telehealth that had:

- significant and ongoing specialist outpatient waiting lists

- substantial impact on patient transport services and travel subsidy reimbursements

- mature and transferrable telehealth models that could be expanded across the state.

Specialist telehealth exceeded targets and provides benefits for patients

Queensland Health implemented specialist telehealth services across 23 sites for 16 clinic types, including antenatal, endocrinology, tele-orthopaedics, and remote chemotherapy. Over three years, HHSs delivered over 21,000 additional specialist telehealth service events, far exceeding the strategy target of 7,750.

From 2019–20, the specialist telehealth program funding was made recurrent, with an additional 13,178 service events delivered in that year.

Figure 4D shows that telehealth outpatient services have trebled since 2016–17, becoming an established mode of delivery. These services were in place and operational prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, enabling Queensland Health to effectively respond to the significant increase in demand resulting from lockdowns and pandemic restrictions. Telehealth is a significant enabler of the health system’s response to the pandemic.

Queensland Audit Office from the Queensland Health Specialist Outpatient Data Collection.

Queensland Health anticipated telehealth appointments would lead to a reduction in travel subsidy reimbursements but could not quantify this due to difficulties HHSs have in attributing travel subsidy expenditure to a particular service in their systems.

Queensland Health used consumer experiences and good news stories from specialist telehealth services to demonstrate success and value-based healthcare. Case study 4 (Figure 4E) highlights one specialist telehealth service—remote chemotherapy, including comments on a patient’s experiences.

| Remote chemotherapy service |

|---|

|

Regional facilities provide remote chemotherapy services under telehealth supervision from oncology specialists. Specially trained local nurses administer the treatment while video linking with specialists at tertiary hospitals. Aim The project uses telehealth to increase access to low-risk chemotherapy treatment services closer to home for cancer patients in regional and rural areas, such as Longreach, Biloela, and Monto. Benefits The remote chemotherapy service improves patient-centred care through local access to specialised services for oncology patients and reduces the emotional and financial costs of travel and accommodation. In addition, increased staff training and education has reduced clinical isolation. Results Providing remote chemotherapy services has a positive impact on patients’ quality of life, providing many patients with more treatment options, local family support, reduced anxiety, reduced travel costs, and timely access to care. A patient in North Burnett who was having several treatments a week commented: ‘Receiving remote chemotherapy services in my hometown saved a 350 km round trip and five hours driving. It meant I could still work for most of the day. Avoiding the drive home was especially welcome.’ |

Queensland Audit Office from project documentation provided by Queensland Health.

5. Implementing journey improvements

This chapter is about whether Queensland Health implemented the 11 investment initiatives (journey improvements) outlined in the Specialist Outpatient Strategy and achieved the intended objectives.

The Specialist Outpatient Strategy consists of 11 journey improvements divided into two key initiative types:

- commissioning of activity—funding for additional new and review appointments and conversion to surgery

- system and journey improvements—implementing contemporary information management systems and innovative models of care.

Were journey improvements implemented as intended?

Queensland Health fully implemented six of the 11 journey improvements in line with the milestones set in the Specialist Outpatient Strategy. Three journey improvements are not yet fully implemented, and it is difficult to assess whether the remaining two were completed as intended due to the lack of specific objectives, measures, and targets.

Figure 5A shows our assessment of progress made by Queensland Health for each journey improvement objective stated in the Specialist Outpatient Strategy.

| Journey improvement | Improvement objective | Progress | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Commissioning of activity |

|||

|

More appointments; less waiting |

By 2017, more patients will be seen within clinically recommended times and current long waits will be reduced. |

Objective met—see Chapter 3 for detailed findings. |

|

|

Elective surgery |

Patients will continue to get their elective surgery at the right time. |

Steps taken to achieve objective, but lacks specific measures, targets, and time frames. |

|

|

Review appointments |

Queensland Health will take steps to enable patient care to continue with the right person at the right time. |

Steps taken to achieve objective, but lacks specific measures, targets, and time frames. |

|

|

Public reporting |

At the moment it is not clear to patients how long they will wait for treatment and that is why Queensland Health will set clear and publicly available targets for specialist outpatient services by 2020. |

Objective met—publicly available performance information is available on Queensland Health’s hospital performance website.

|

|

|

System and journey improvements |

|||

|

Clinical prioritisation criteria (CPC) |

By late 2018, CPC will be fully implemented across Queensland GPs and public hospitals. |

CPC website developed; it currently covers 29 specialities, representing 81 per cent of conditions for all patients waiting for a specialist appointment. 4,500 users accessed the CPCs in June 2021. However, anyone can access the publicly available CPCs. There is no information available to assess how many of Queensland’s 6,000-plus GPs are using the CPCs. |

|

|

Referral services directory |

By 2020, GPs will have access to an online statewide directory of public hospital services to better inform and direct their referrals. |

A referral services directory (RSD) was developed and is operating in 11 of 16 HHSs, with the RSD to be rolled out to the remaining five HHSs by March 2022. |

|

|

GP smart referrals |

Phasing in from 2017, GP referrals will be submitted by secure electronic messaging to Queensland’s largest public hospitals. |

Nine HHSs have smart referrals enabled, covering all but one larger public hospital. Not all GPs use the smart referral software that also enables them to view the RSD. Currently, 22 per cent of the GPs with compatible practice management software are using smart referrals. |

|

|

Patient online portal |

By 2020, patients will have the ability to manage their specialist appointments online through a patient portal, which will include all the necessary information relating to their specialist appointment. |

YourQH portal was designed and implemented at one of the two initially planned hospitals. It was implemented at Children’s Hospital Queensland HHS in July 2020. Queensland Health plans to implement the portal at two further HHSs by March 2022. |

|

|

Health provider portal |

By 2018, Queensland GPs will have the ability to access components of their patients’ public hospital medical records. |

Objective met—currently 4,000 registered users. |

|

|

New models of care |

Phasing in from 2017, there will be additional new models of care across Queensland, including models using allied health. |

Objective met—see Chapter 4 for detailed findings. |

|

|

Specialist telehealth |

By 2020, Queenslanders living in rural and remote areas will have greater access to specialist care via telehealth services. |

Objective met—see Chapter 4 for detailed findings. |

|

| Notes: | Objective met. | Objective not fully met. | Unable to assess due to lack of specific target. |

Queensland Audit Office from project documentation and interviews with Queensland Health.

Measuring success

Project objectives should be clear statements that focus on the desired outcomes, describe what the project seeks to achieve, and define ways to measure success. They should be specific and measurable with set time frames and targets.

The objectives for many of the Specialist Outpatient Strategy journey improvements could have been better. While most objectives defined the time frame, they did not set measurable targets. For example, while Queensland Health met the general practitioner (GP) smart referral and health provider portal objectives in principle, it did not set targets for how many GPs it intended to have using the systems.

For two journey improvements (elective surgery and review appointments), it was more difficult to fully assess whether Queensland Health met the objectives and realised intended benefits. This is because the strategy did not include specific measures, targets, or time frames. However, Queensland Health reports on elective surgery performance on its website and in its service delivery statements.

How was funding allocated?

Queensland Health allocated around $595 million over six years for commissioning of activity, and system and journey improvement projects. The commissioning of activity funding was provided to HHSs annually and managed through service-level agreements and performance management meetings.

Figure 5B shows a breakdown of funding allocated from 2015–16 to 2020–21.

|

Journey improvement type |

Total |

Percentage of |

|---|---|---|

|

Commissioning of activity |

471,134 |

79% |

|

System improvement projects |

76,112 |

13% |

|

New models of care |

27,677 |

5% |

|

Specialist telehealth |

19,740 |

3% |

|

Total |

$594,663 |

100% |

Queensland Audit Office from project documentation provided by Queensland Health.

In Chapter 3, we noted that Queensland Health allocated the additional commissioning of activity funding to the HHSs with the greatest number of long waits or with a demand/capacity imbalance.

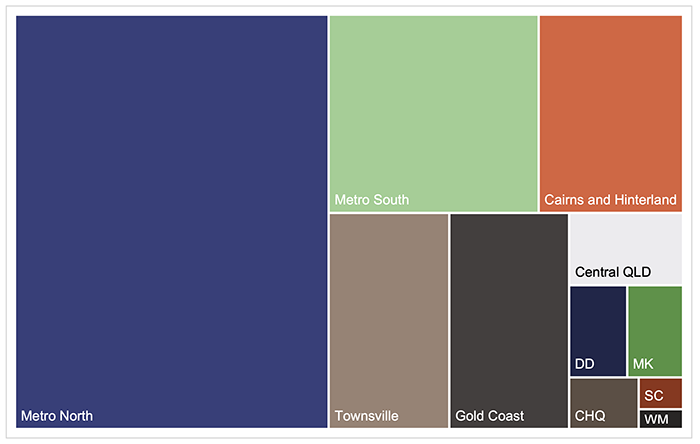

Figure 5C shows that, from 2015–16 to 2018–19, five HHSs received 90 per cent of the activity funding, with around 60 per cent allocated to Metro North and Metro South HHSs.

Notes: Central QLD—Central Queensland, DD—Darling Downs, MK—Mackay, CHQ—Children’s Health Queensland, SC—Sunshine Coast, WM—West Moreton. Data on additional activity funding by HHS is only available from 2015–16 to 2018–19. From then, funding became recurrent.

Queensland Audit Office from project documentation provided by Queensland Health.

Four of the five HHSs receiving the greatest proportion of commissioning of activity funding were set targets to reduce long waits by 1 July 2017. Cairns and Hinterland, Gold Coast, and Metro North HHSs achieved those targets. Metro South reduced its long waits by around 60 per cent but did not meet its target. Townsville HHS was not set a specific target but cleared all long waits by 1 July 2017.

Are system and journey improvements effective?

New systems have created process efficiencies for hospitals and GPs, and improved the patient journey and referral quality. Queensland Health developed five new systems, and advise that they will all be fully implemented at HHSs by March 2022.

Not fully implementing and rolling out all planned system improvements in line with the Specialist Outpatient Strategy objectives means that benefits to the patient journey are not yet optimised. A low uptake from GPs on using smart referrals and clinical prioritisation criteria limits expected benefits and efficiencies.

Innovative systems have improved efficiency and quality

Smart referrals are a key part of the Specialist Outpatient Strategy and a complex digital transformation for Queensland Health. The system combines an online services directory, electronic referral management, and clinical decision support tools (the clinical prioritisation criteria), which are integrated with GP management systems.

Benefits of smart referrals include:

- improving the management and tracking of patient referrals along all stages of the healthcare journey

- standardising both the referral process and the referral criteria

- optimising the overall quality of referrals.

By providing better information on the patient’s condition, diagnosis, and reason for referral, the clinical prioritisation criteria have improved the quality of referrals. The proportion of referrals returned by HHSs to referring practitioners for further information has reduced—from around 3.75 per cent in June 2016 when the clinical prioritisation criteria website went live, to less than 0.5 per cent in June 2021.

Low uptake of smart referrals by GPs limits benefits

Smart referrals can manage all patient referrals for specialist outpatient services statewide. Potential benefits include a more streamlined and visible referral process, and better-quality referrals that reduce rework and duplication. However, GP uptake of electronic referrals is low, significantly reducing journey improvement opportunities.

Smart referrals are compatible with two GP practice management systems, and Queensland Health reports that around 80 per cent of the 6,000-plus GPs in Queensland have these compatible systems. Of that 80 per cent, 22 per cent (about 1,055 GPs) are using smart referrals.

GPs send the remaining referrals by email, fax, or post. Duplicate submissions by multiple means are common. Some referrals are handwritten.

These outdated and sometimes conflicting processes complicate the categorisation and referral system and create inefficiencies and delays in the patient journey.

Other factors affecting uptake of smart referrals by GPs include a:

- complex onboarding and installation process

- varied level of promotion, training, and support from HHSs and Primary Health Networks

- lack of support from GPs (the system is seen to offer limited benefit to GPs).

As part of Connecting your Care, Queensland Health aims to strengthen the relationship and interface with GPs. This includes strategically engaging with GPs to achieve more widespread use of smart referrals. Queensland Health should consider working with Primary Health Networks to identify and deliver any required training and support.

Was the program well managed?

Queensland Health established a structured and consistent approach to manage the implementation of the Specialist Outpatient Strategy and most of the 11 journey improvements, using good practice methods. This was followed for the first two years of the program, but later program monitoring and governance practices were less consistent and visible as the initiatives became part of normal operations.

We reported two minor findings to management during this audit about how Queensland Health managed and evaluated the program.