Overview

In 2020–21, Queensland Government entities distributed $2.8 billion in grants – to community groups, local governments, businesses, and others – to support the objectives and priorities of the government. Many public sector entities manage these grants, and each has its own practices. These practices must have effective internal controls to achieve maximum benefit from the grants awarded, and should ensure the entities are accountable, transparent, and neutral in decision-making, while achieving value for money.

Tabled 19 July 2022.

Report on a page

In 2020–21, Queensland Government entities distributed $2.8 billion in grants – to community groups, local governments, businesses, and others – to support the objectives and priorities of the government. This report provides insights into where Queensland Government grants go.

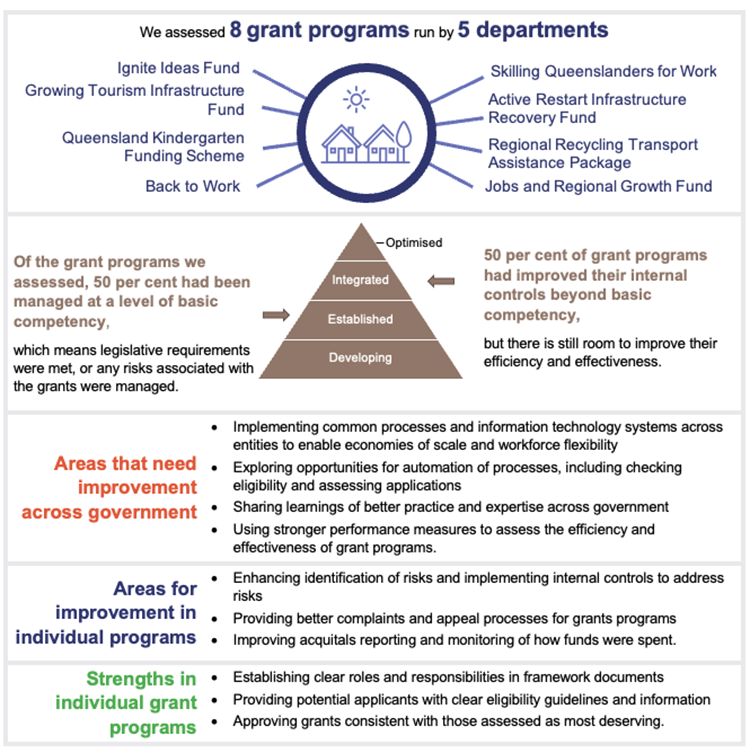

It also analyses the strengths and weaknesses of the internal controls (people, systems, and processes) used by 5 departments in managing 8 grant programs. We selected the departments based on the size and risks of the grants they manage.

Clearer information about grants is needed

Each year, departments, and the Queensland Reconstruction Authority, publish information on grant expenditure on the Queensland Government’s Open Data website, including who received funding, where (geographically) it was spent and what it was for. This is partly for transparency and accountability, and partly so people can understand what funding is going to their local communities.

The government could do more to make grant information more user friendly and accessible, with an interactive dashboard. With the dashboard comes the opportunity to learn what is important to the public, so departments can focus on making that data complete and accurate. This will allow the information to be published more regularly in future, making it more timely and useful.

The quality of grants management processes varies

The departments in charge of the 8 grant programs have demonstrated at least basic competency in managing them. Some have improved their processes over time to reflect better practice. In these instances, departments have achieved improved efficiency by automating processes. We found that older grant programs (which have had longer to improve their internal controls) tend to have more efficient and effective systems and processes than those of more recent duration.

For all 8 of the programs, departments have developed and applied clear eligibility guidelines in considering applications for grants, and have consistently assessed applications against the published criteria.

Departments need to improve how they identify and manage the risks associated with specific grants. They must be able to demonstrate that their design of grant programs takes the risks into account. This will help them to be efficient and to deliver better outcomes for the community.

Some departments have collaborated on projects to share knowledge on grants management and build capability across the government. It is a good start, and if the initiative expands across the government to more departments, there are real opportunities to build greater consistency, workforce flexibility, and economies of scale.

Departments need to measure grant programs better

While all grant programs use a range of metrics (for example, applicant numbers, budget spent, or the number of jobs created), more needs to be done to objectively measure the performance of the recipients and the outcomes of the program. Measures also need to be in place to alert departments early in the process if grants are at risk of not achieving their targets until it is too late.

Departments need to implement strong performance measures when establishing grant programs. Without them, it is not easy to know how effective the grant is and what decisions need to be made about future funding allocations or whether programs should be discontinued or modified.

1. Recommendations

We make the following 8 recommendations in this report:

Queensland Treasury should reassess developing an interactive tool to provide useful information on grants |

|

| REC 1 |

We recommend Queensland Treasury reassess the costs and benefits of developing an interactive dashboard for the public using the Queensland Government Investment Portal – Expenditure Data. The interactive dashboard could then be monitored to better understand the information needs of users and what data should be collected and published in the future. |

All departments should provide explanations for why information has been omitted |

|

| REC 2 | Queensland Treasury should update the instructions sent to agencies on preparing grant information for publication on the Open Data website as part of the Queensland Government Investment Portal – Expenditure Data, to require agencies to explain why mandatory information has not been provided for some grants. Examples of appropriate exclusions should be included in the instructions. The explanation should then be published with the grant information. |

All departments and the Queensland Reconstruction Authority (agencies) should improve their collection and checking of grant information to ensure published information is complete |

|

| REC 3 |

When agencies initially assess grant applications, we recommend they collect all information that is required to be published on the Open Data website as part of the Queensland Government Investment Portal – Expenditure Data. We also recommend agencies check the completeness of grant information provided to Queensland Treasury for publishing to ensure there is no missing information. |

All departments should self-assess their grant management processes against the Queensland Audit Office’s maturity model and report the outcome of the self-assessment to those charged with governance |

|

| REC 4 |

All departments should use the grants management maturity model available on our website to self-assess the strengths and improvement opportunities of their grant programs. The result of the maturity assessment should be reported to audit committees or other relevant oversight bodies. Where the results do not meet performance expectations, a plan should be developed and implemented to strengthen internal controls over a specific period. This should include working closely with other departments on whole-of-government grants initiatives. |

The Department of State Development, Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning should lead improvements in grants management across government |

|

| REC 5 |

The Department of State Development, Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning should work with other departments to:

|

All departments should enhance risk management of grants |

|

| REC 6 |

We recommend all departments assess the risks of grant programs from the perspective of:

|

All departments should enhance the acquittal of grants |

|

| REC 7 |

We recommend all departments enhance the acquittal of grants by:

|

All departments with significant grant programs should develop and implement stronger key performance measures to better monitor grant program performance and outcomes |

|

| REC 8 |

We recommend all departments with significant grant programs ensure they develop and periodically monitor key performance metrics to measure:

|

Reference to comments

In accordance with s. 64 of the Auditor-General Act 2009, we provided a copy of this report to relevant entities. In reaching our conclusions, we considered their views and represented them to the extent we deemed relevant and warranted. Any formal responses from the entities are at Appendix A.

2. Grant funding in Queensland

The Queensland Government provides grants and other funding – to community groups, local governments, businesses, and others – to support the objectives and priorities of the government. This chapter provides insights into where the grant funding goes and what the money is used for.

In analysing grant expenditure to provide these insights, we also identified ways in which the Queensland Government could share more useful information about how it spends this money.

Chapter snapshot

Overview of Queensland’s grant expenditure

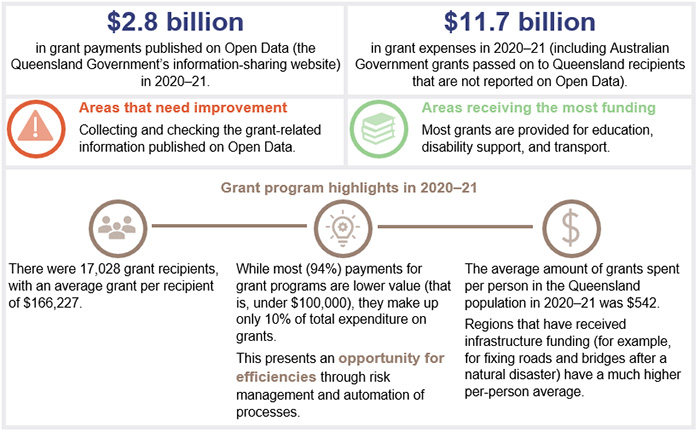

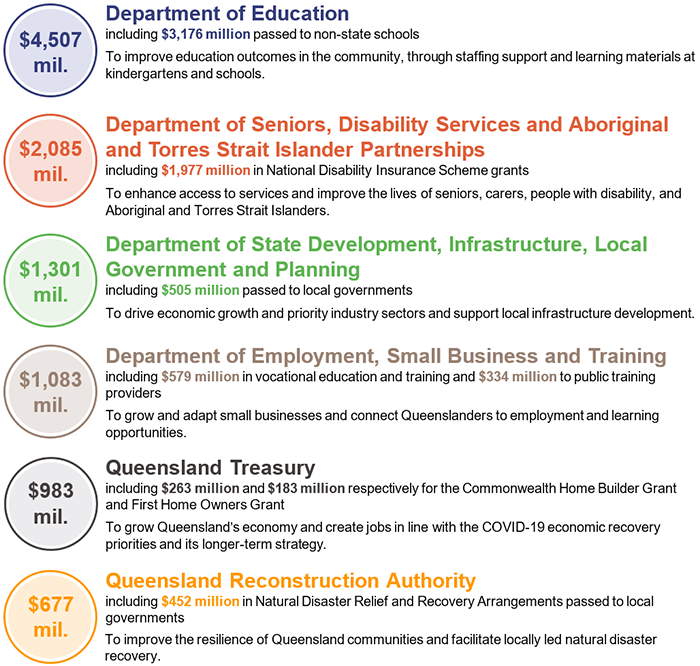

In 2020–21, 52 entities across the Queensland Government recorded $11.7 billion in grant expenses, including 21 core departments and 46 other entities. Figure 2A provides a summary of the grants provided by the 6 entities with the largest grant expenses in the Queensland Government in 2020–21.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office from the 2020–21 Report on State Finances of the Queensland Government – 30 June 2021.

Detailed information on grants is published on Open Data

Governments must share timely and reliable information about the grants they award. Members of the public will only have confidence in the quality and integrity of the grants process if they see it as open and honest. Each year, Queensland Government departments and the Queensland Reconstruction Authority publish information on funding provided for frontline services and grant programs on the government’s Open Data website.

Open Data

The Queensland Government Open Data Policy Statement commits to making important data freely available for anyone to easily access, use, and share. It is intended to foster transparent and accountable government, and support better service delivery. Each department is required to develop and publish its own Open Data strategy and data release schedule.

The Grants, frontline service procurement and other assistance data policy (part of the Queensland Government Enterprise Architecture) supports the objectives of the Open Data policy statement. It is intended to provide a consistent approach to reporting and publishing grants, frontline service procurement, and other assistance information, by defining the data to be collected.

In accordance with this policy, Queensland Treasury collects information on grant expenditure from departments and the Queensland Reconstruction Authority. The Queensland Reconstruction Authority, while not a department, is required to publish information on the Open Data website due to the significant grants it provides after natural disasters. This information is published once a year on the Open Data website as part of the Queensland Government Investment Portal – Expenditure Data.

The information published for grants includes:

- name of the grant program and its purpose

- name of the funding agency (the agency responsible for the grant – the department or the Queensland Reconstruction Authority)

- information about recipients

- local government area where the grant program is delivered

- amount paid

- start and end dates for the grant.

Of all the expenditure published on Open Data for 2020–21, the funding agencies classified $2.8 billion as grants. This information is different to that reported in their financial statements and summarised in Figure 2A, because it reflects cash payments, while financial statements are prepared under a different accounting method.

Open Data also excludes grants that are paid on behalf of other entities, for example Australian Government grants of $3.7 billion for non-state schools and local governments (which pass through Queensland Government entities before they reach their intended recipients). We have used Open Data to provide the following insights, as it has detailed information about who received grant funding and for what purpose, and where the recipients are located.

We have presented the grants information gathered for this report on an interactive map of Queensland available on our website at www.qao.qld.gov.au/reports-resources/interactive-dashboards. Readers can use this to explore and compare information on grants, and to access extra information we consider relevant to understanding the local context for specific grants.

Recipients of Queensland Government grants per Open Data

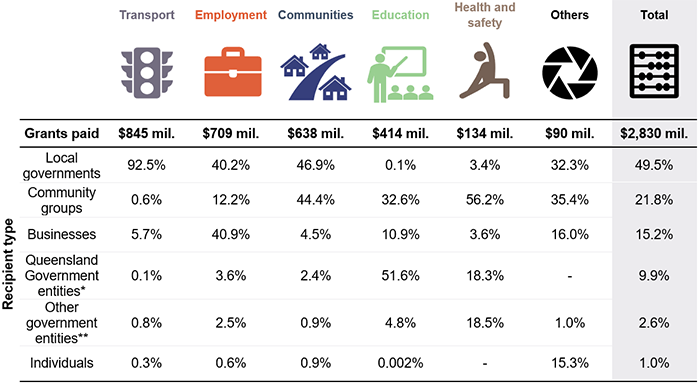

Figure 2B details the distribution of the $2.8 billion in grants – by sector and recipient type.

Notes: *Queensland Government entities are those included in the 2020–21 Report on State Finances of the Queensland Government – 30 June 2021. **Other government entities include other state entities (for example, universities) and Australian Government entities.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office based on information on the Queensland Government’s Open Data website.

The largest Queensland Government grant programs paid to entities outside the state government included:

- $452 million to restore public infrastructure impacted by natural disaster – mostly to local governments

- $200 million for construction work on transport infrastructure – mostly to local governments

- $161 million for kindergarten and long day care services – mostly to community groups

- $144 million to mitigate the impact of the waste levy on households – to local governments

- $139 million to support economic recovery projects following COVID-19 – to local governments

- $100 million to support employment impacted by COVID-19 – mostly to businesses.

Queensland Government entities received nearly 10 per cent of total grant funding. This was mostly for TAFE Queensland ($202 million) and included contributions towards its higher operating costs as a public training provider.

Regions that have received Queensland Government grants

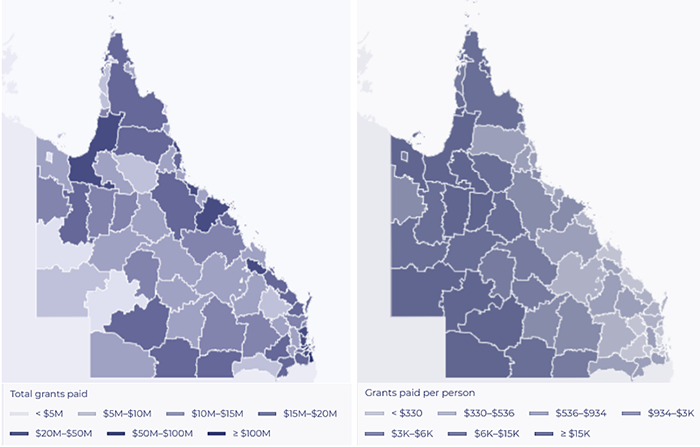

Recipients of grant funding are located across Queensland. The distribution of grants across the state can be analysed in different ways, depending on the purpose for which grant funding is provided. Grant funding often reflects the size of the local population, but also the needs of the community.

Figure 2C compares the total grants paid, and the average paid per person in a region.

Note: This regional analysis excludes funding that was provided for services over multiple local government areas or statewide ($625.4 million – 22.1 per cent of grant funding), as well as funding that was provided interstate or considered not applicable for assigning to a local government area ($30.9 million – 1.1 per cent of grant funding).

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office based on information on the Queensland Government’s Open Data website and on population data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

South East Queensland received 32.5 per cent of grants, with 73 per cent of Queensland’s population living in this area. These grants had a strong community focus, including programs relating to sport and recreation facilities, kindergarten programs, and arts initiatives. A lot of programs also had an employment and education focus, including for training schemes and COVID‑19 assistance packages.

Regions outside of South East Queensland received 44.3 per cent of grants, with most grants going to Townsville, Whitsunday, and Cairns. Most grants in Townsville and Cairns were for employment purposes, including COVID‑19 assistance packages. These regions have the largest populations outside of South East Queensland. They were significantly impacted by COVID-19 restrictions, with 20 per cent of the workforce associated with retail trade, accommodation, and food services. Whitsunday received the largest share of natural disaster funding following Cyclone Debbie in March 2017.

Some grants are provided for statewide purposes (for example, contributions to public training providers), or to benefit multiple regions. These represented 22.1 per cent of total grants.

The average amount of grants paid across the state was $542 per person. Sixteen local government areas received more than $10,000 in grant funding per person. The average population in these areas was 719 people, and funding was usually for high dollar value infrastructure projects, often after a natural disaster or to support economic development in a region.

Opportunities for efficiencies in grants management

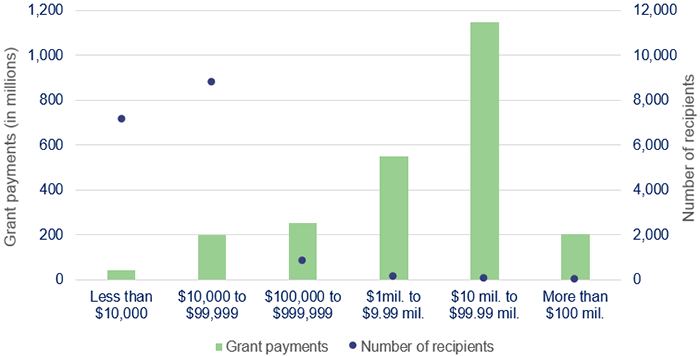

In 2020–21, the Queensland Government provided grants ranging from a few thousand dollars to hundreds of millions.

Figure 2D shows that most individual grants paid were less than $100,000. There were 15,982 recipients of these lower value grants, and they received a total of $239.1 million in grants, or an average grant of $14,961. A much smaller number of individual grants of over $100,000 were paid – 1,046 recipients received a total of $2.2 billion, or an average grant of $2.1 million.

Overall, 94 per cent of recipients received 10 per cent of the total grant funding for 2020–21.

Note: This analysis excludes funding of $439.5 million (15.5 per cent) that did not specify the recipient.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office based on information on the Queensland Government’s Open Data website.

Each program has different risks, with the level of risk influenced by the dollar value of grants, the number of recipients, and other factors including the nature of the grant and speed of delivery.

For example, if a grant for millions of dollars is awarded to construct an asset, it is important that:

- the asset has been appropriately designed so it will be compliant with local building regulations and achieve the intended benefits for the community

- the project has been accurately costed so it can be delivered within budget

- the recipient has the skills and experience to manage such a large project.

It is likely the project will be delivered over several years, and grants management staff will monitor the progress of the project and compliance with the grant agreement. While these grants are low in number, they represent a high proportion of total funding, with risks that need to be carefully managed throughout the grant program.

In contrast, a different grant may provide a consistent amount of funding to all concession card holders to subsidise the cost of a community activity. Applicants will need to provide sufficient evidence of their eligibility to claim the grant up front, but the ongoing risks are lower. For this reason, there is greater opportunity to automate this type of grant, increasing efficiency.

Entities need to understand the risks and opportunities of each grant, so they can appropriately design the program. This includes ensuring their processes are as efficient as possible, so the costs of administration do not exceed the benefit provided to the community.

Entities also need to be mindful of the cost of administration for grant recipients. While over 89 per cent of grant recipients only received a grant from one funding agency, the remaining 11 per cent received grants from between 2 and 12 agencies. This was worst for councils, which on average received grants from 8 agencies. The Department of State Development, Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning has a model that recognises this and aims to reduce the impact on councils of different grant processes being followed by agencies.

However, there is no such process for the rest of government. On average, Queensland universities received grants from 5 funding agencies, but one engaged with up to 8 agencies. Nearly 200 community groups received grants from at least 3 funding agencies, and one engaged with up to 12 agencies. This was exacerbated by continued government restructuring, as highlighted in State entities 2021 (Report 14: 2021–22).

Chapter 3 explores other opportunities for efficiency in processes for managing grants, as well as the use of efficiency and effectiveness performance measures.

Some important information has not been published on Open Data

Queensland Treasury provides funding agencies with instructions on how to prepare information for Open Data. The instructions explain the mandatory fields (for example, funding agency, program title, purpose, and category) and optional fields (such as sub-program title, and the opening and closing dates). It also explains how to check and approve the information. Each agency’s chief financial officer or their delegate is required to approve the information. Queensland Treasury relies on this process and does not do any further checks over the completeness or accuracy of the information provided by agencies before it publishes it on the Open Data website.

We found the grant information systems used by agencies have not always collected information in the format required. In these instances, agencies used their judgement to determine when to combine and allocate funding into different categories, such as the geographical area in which the program is delivered. In some instances, agencies have left several information fields blank, or provided data that was not fully compliant with Queensland Treasury’s requirements.

Figure 2E shows our analysis of the quality and completeness of the information on the Open Data website.

| Information with good data quality | Per cent of information complete | Information with poor data quality | Per cent of information complete |

|---|---|---|---|

| Funding agency | 100% | Legal entity name of the recipient | 84% |

| Purpose | 100% | Australian Business Number (ABN) | 84% |

| Category | 100% | Legal entity postcode | 83% |

| Funding use – capital (to construct assets) or operational | 100% | Postcode where the program is delivered | 74% |

| Program title |

99% |

Funding start date and funding end date | 40% |

| Local government area where the program is delivered | 99% |

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office based on information on the Queensland Government’s Open Data website.

In total, agencies reported the legal entity name of 17,028 recipients; but did not do so for 40 programs (worth $439.5 million). In some instances, this was because payments had been made to individuals, and this information was legitimately withheld to maintain their privacy, but this was not always the case.

The lack of information on some grant programs could limit agencies’ ability to check for overlapping funding to the same recipient for the same purpose. According to Queensland Treasury’s Financial Accountability Handbook, relationships with other funding bodies, and information-sharing on programs with shared objectives, are essential elements of grants management.

The Open Data website is also an important way for the public to obtain consistent information about the grants that have been awarded and paid by the Queensland Government. Where this information is not complete, it may reduce the public’s confidence in the quality and integrity of the grants process. It may also limit the ability of businesses and community groups (including those who have previously applied for grant funding or may do so in the future) to understand what grants the government has provided, and how they can apply for future funding and work with government in their service delivery.

Opportunity to rationalise data collected and improve public use of it

We found most funding agencies were concerned about the resources and time required to prepare the information. They expressed interest in having a better understanding of what the public finds useful and in knowing whether users need all the mandatory or optional data currently required for the Open Data website.

The Department of Communities, Housing and Digital Economy collates statistics on users’ interactions with information on the Open Data website. The website has a low number of visitors and downloads. This indicates potential users (including the public, grant recipients, and other departments that manage grants) do not know the information is available, do not find it useful, or do not find it easy to access or read.

The presentation of expenditure information on the Open Data website has evolved since it was first published in 2012. In 2018, it changed to its current form, being direct access to the raw data. This followed engagement with existing users, which indicated their needs could be met with access to this data, which would enable them to export and present it to meet their own requirements.

However, the way information is consumed has changed since 2018. Given the importance of community trust in grant processes – and the key role accurate and readily available information plays in achieving this – more needs to be done to ensure the most useful data is provided and widely accessed.

An interactive dashboard (a graphical summary with which users can interact to select different types of information in varying degrees of detail) could make the information on grants more accessible and useful. The dashboard could also enhance the link between the Queensland Government Grants Finder (which explains the assistance that is available) and the funding that is awarded.

The dashboard could clarify what information is of most relevance to people. This would allow agencies to better focus their attention on collecting and checking relevant data to make sure it is complete. A more efficient process could also allow the information to be published more regularly than once a year, making it more timely and useful.

|

Recommendation 1 Queensland Treasury should reassess developing an interactive tool to provide useful information on grants |

| We recommend Queensland Treasury reassess the costs and benefits of developing an interactive dashboard for the public using the Queensland Government Investment Portal – Expenditure Data. The interactive dashboard could then be monitored to better understand the information needs of users and what data should be collected and published in the future. |

|

Recommendation 2 All departments should provide explanations for why information has been omitted |

| Queensland Treasury should update the instructions sent to agencies on preparing grant information for publication on the Open Data website as part of the Queensland Government Investment Portal – Expenditure Data, to require agencies to explain why mandatory information has not been provided for some grants. Examples of appropriate exclusions should be included in the instructions. The explanation should then be published with the grant information. |

|

Recommendation 3 All departments and the Queensland Reconstruction Authority (agencies) should improve their collection and checking of grant information to ensure published information is complete |

|

When agencies initially assess grant applications, we recommend they collect all information that is required to be published on the Open Data website as part of the Queensland Government Investment Portal – Expenditure Data. We also recommend agencies check the completeness of grant information provided to Queensland Treasury for publishing to ensure there is no missing information. |

3. Grants management in Queensland

Many Queensland Government entities manage grants, and each has its own practices. This chapter analyses the internal controls (people, systems, and processes) used to manage grants across 5 departments. We selected them based on both the dollar value and risk of their grant programs. We did not just focus on the high dollar value programs highlighted in Chapter 2.

Chapter snapshot

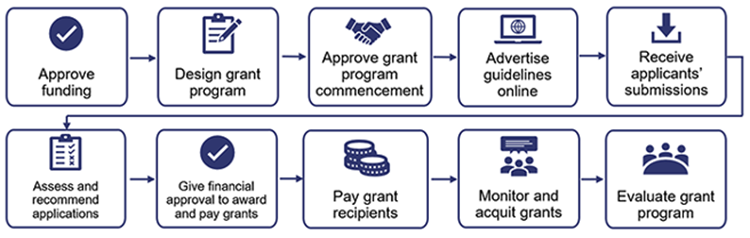

The grants management process

Grants can be awarded in 3 ways:

- on the basis of demand – all applications are approved if eligibility criteria are met

- on the basis of competition – applications are assessed according to selection criteria set by the department. Departments only recommend those applicants who best meet the criteria for grant funding. A degree of subjectivity is involved in the assessment of the applications

- through direct payments – grants are awarded without application. This can include election commitments or significant projects involving other levels of government.

All grant programs have similar (but not identical) phases, as shown in Figure 3A.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office.

Most departments we reviewed have appropriate grants management processes, but there is room to improve

Public sector entities must have effective internal controls to achieve maximum benefit from the grants they award. The controls should ensure the entities are accountable, transparent, and neutral in decision-making, while achieving value for money.

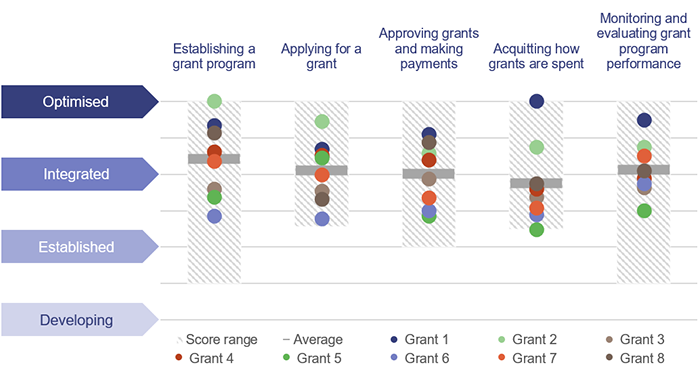

We developed a model to measure the maturity (the increase in efficiency and effectiveness) of the internal controls departments have used to manage the 8 grant programs we assessed. The model includes 35 questions across 5 grant processes. Figure 3B summarises the results, showing:

- the average result from these questions for each grant program as a coloured dot

- the lowest and highest results for individual questions within each process across all grant programs as a shaded range (score range)

- the average result for each grants process as a solid line (average).

We use 4 levels of maturity, which are defined as:

- developing – an entity does not have this control, or it is not operating effectively, so the identified risk (the risks specific to a particular grant) is not managed

- established – an entity shows basic competency in this area, so legislative requirements are met, or the identified risk is managed

- integrated – an entity is developed in this area or regularly demonstrates this, so controls work together to respond to the identified risk; however, the efficiency or effectiveness of controls could still be improved

- optimised – the entity consistently demonstrates this control and is a leader of best practice in this area.

We assessed the average maturity of the 8 grant programs as ‘established’ to ‘integrated’ and considered some parts of the process as ‘optimised’.

We found the grant approval and acquittal processes were the least mature aspects of grants management. These areas are important in demonstrating impartiality in approving grant allocations and, at the other end of the process, in ensuring grants have been used appropriately and have delivered the desired results.

|

Recommendation 4 All departments should self-assess their grant management processes against the Queensland Audit Office’s maturity model and report the outcome of the self-assessment to those charged with governance |

|

All departments should use the grants management maturity model available on our website to self-assess the strengths and improvement opportunities of their grant programs. The result of the maturity assessment should be reported to audit committees or other relevant oversight bodies. Where the results do not meet performance expectations, a plan should be developed and implemented to strengthen internal controls over a specific period. This should include working closely with other departments on whole-of-government grants initiatives. |

Building greater consistency and flexibility in grants management

For the 8 grant programs across the 5 departments, 4 different information technology systems and one spreadsheet were used for grants management. The systems had varying functionality, and some required expertise that is not easily transferred to other systems.

Not surprisingly, the number and variety of different systems affects the consistency of processes across government and the ease with which information can be collected and published on the Open Data website.

It can also limit workforce mobility (the ability to move staff around) to meet rapid demand for large-scale programs, such as disaster relief funding or COVID-19 financial support. Implementing these grant programs quickly can be challenging. The administering entities need to balance the urgency of providing funding to those in need, with ensuring the program is accountable and efficient in distributing funds.

The Rapid Relief Grant Capability Project was developed to make it easier to quickly deliver these sorts of grant programs. The Department of Agriculture and Fisheries led this project and the grants administration working group as part of the Queensland Government’s Savings and Debt Plan. The project involved various Queensland Government entities, with the intent of sharing knowledge and building capability across government.

It identified the need for better planning for a ‘surge’ workforce to quickly meet demand. Other initiatives included standardising templates and eligibility criteria, clarifying governance arrangements, and developing a guide for program delivery. The project also explored opportunities for automation of processes and shortlisting of technology solutions.

Other projects are also underway. The Department of State Development, Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning has developed a new Grants to Local Government Model. The model is simple, adaptable and designed to make it easier for councils to apply for grants, deliver projects and report on progress. The department is also commencing a project to improve grant maturity across government. The project includes an advisory group with several deputy directors-general from departments that provide economic and financial assistance grants.

These projects are an important step towards building greater consistency, economies of scale, and flexibility.

In our recent report on Enhancing government procurement (Report 18: 2021–22), we identified several areas where effective government procurement can deliver better value for money and savings across government. Collective negotiations at a whole-of-government level could deliver a better deal for a common information technology system that could be licensed across the Queensland Government.

Clear leadership and accountability are needed to fully realise the benefits of these projects across government. The Department of State Development, Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning is well positioned to fill this role, given the volume and value of its grants programs and its recent initiatives to improve grants management within the Queensland Government.

|

Recommendation 5 Department of State Development, Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning should lead improvements in grants management across government |

|

The Department of State Development, Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning should work with other departments to:

|

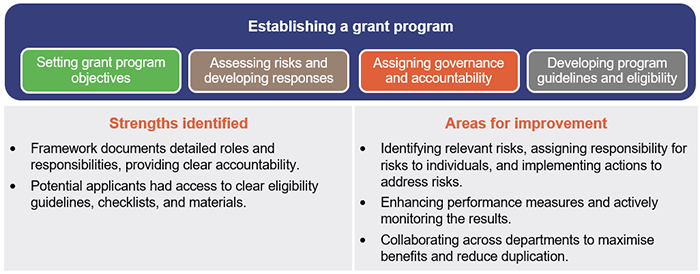

Establishing a grant program

In establishing a grant program, entities identify the key aims of the program and design a governance structure to monitor and manage the process and outcomes. The roles and responsibilities of all parties should be clearly established up front.

Figure 3C shows the strengths and the areas for improvement we identified in the establishment of the 8 grant programs we assessed.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office from our maturity model assessment of 8 grant programs.

All grant programs we assessed had established clear roles and responsibilities and had published information on the grant program for potential applicants.

It is also important in establishing the grant program that departments identify what the program is intended to achieve and how they will measure its success. This could be improved, and is explored later in the chapter, under ‘Monitoring and evaluating grant program performance’.

Only one grant program had strong collaboration with other Queensland Government entities, as it was part of a broader Queensland Government initiative. If they do not collaborate, different departments may provide multiple programs with a similar objective. This dilutes the benefits obtained from individual programs, and duplicates administrative processes and costs – both for government and the grant applicants.

Risk management was the area in which departments could improve the most, so we have explored that further here.

Identifying the risks of each grant program and implementing action plans to address them

The design of a grant program depends on what it is intended to achieve. Entities must clearly define the objectives of the program and comprehensively assess the risks of not achieving those objectives. This will affect how the program is advertised, whether funding is available to all eligible applicants or only those who best meet the criteria, whether grant recipients need to report back on how they spend the grant, and how grant program performance will be monitored.

In the case of rapid response programs (which need to be established at short notice due to an urgent need), it is especially important to understand the risks that may need to be accepted because of the speed with which the program is rolled out. For example, if payments need to be made quickly, extensive checking of eligibility would slow down the payment process. Alternatively, departments may decide to automate more aspects of the eligibility assessment, including by collaborating with other Queensland Government entities to share data.

If departments understand the risks associated with a rapid response program, they can reflect this in their design of the eligibility criteria. While this may mean they pay a small number of people who were not within the scope of the grant program, it will also mean they can assess the criteria quickly and easily – delivering the desired outcome more efficiently. This risk may be acceptable for grant programs with individual grant payments of a small dollar value, but it will not be for those with a higher dollar value. Departments may then need more checks in place to reduce the risk.

All the grant programs we assessed had documented some risks in a register. However, they had not always consistently recorded all relevant risks or identified the people responsible for ensuring the risks are appropriately managed. Nor had they always clearly outlined the actions required to address the risk, or actively managed and monitored those actions.

|

Recommendation 6 All departments should enhance risk management of grants |

|

We recommend all departments assess the risks of grant programs from the perspective of:

|

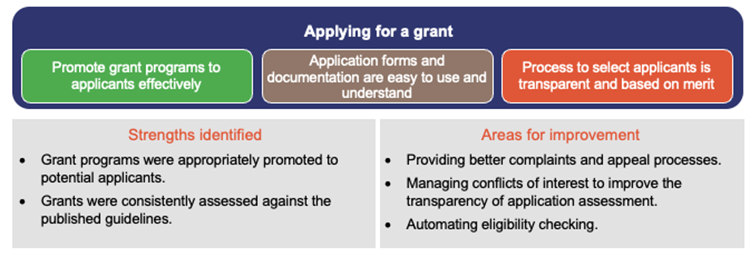

Applying for a grant

Efficient and effective grant application processes promote a grant program to eligible applicants. They also make it easy for applicants to apply and departments to assess applications against the pre‑determined eligibility criteria of the grant. The selection process must follow the published guidelines developed when the grant program was established, and that documentation must clearly explain what was considered in the process of selecting and approving recipients of the grant.

Figure 3D shows the strengths and the areas for improvement we identified in the grant application process across the 8 grant programs we assessed.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office from our maturity model assessment of 8 grant programs.

In this section, we have explored the areas in which the departments need to improve. Automation of processes can make a big difference to the efficiency with which departments process applications.

Departments could automate their eligibility and assessment processes

All grant programs we assessed had strategies to promote their programs to potential applicants, and all grants were consistently assessed against the published guidelines. However, the efficiency of the assessment process varied due to the degree of automation involved.

One example of better practice involved a grants management system that allowed applicants to submit their application online. Certain fields such as Australian Business Numbers and addresses were validated by the system through the application process. Compliance and licence checks were also performed against information provided by the Office of Fair Trading. Only eligible applications were then assessed by a grants officer against the selection criteria to determine which applications best met the criteria. This was consistently documented on an assessment form within the system. Information was automatically extracted from the system for analysis and reporting to a moderation panel.

The learnings from this department would be of real benefit to others.

Avoiding conflicts of interest in staff, and managing complaints from applicants

Departments can build confidence in the selection process by ensuring they appropriately manage potential conflicts of interest. Employees should avoid conflicts of interest (or even a perception of them) to maintain the integrity of grants management. These conflicts can arise when an employee’s interests outside of work (for example, their family relationships, business interests, hobbies, or volunteering) overlap with grants they may be involved in assessing, approving, or managing.

Overall, we found the management of conflicts of interest for the 8 grant programs we assessed was good. However, some departments could improve by reinforcing training and guidelines in this area. To strengthen the overall integrity of the process, conflicts of interest could also be considered for all employees involved in the grants management process – not just for the selection panel members, as is the case in some departments now.

As with managing potential conflicts of interest, effective complaints management supports the integrity of the selection process. A good complaints management system allows applicants to raise concerns and for them to be addressed transparently.

One program uses an online form to send information via the complaints management system to the responsible officers to promptly review and respond. However, 2 programs had no direct method to lodge a complaint or start an appeal process about grants. Instead, they relied on general department‑wide complaint processes.

Complaints and appeal processes should be easy to access and should deliver a prompt response to applicants who are appealing against decisions or processes.

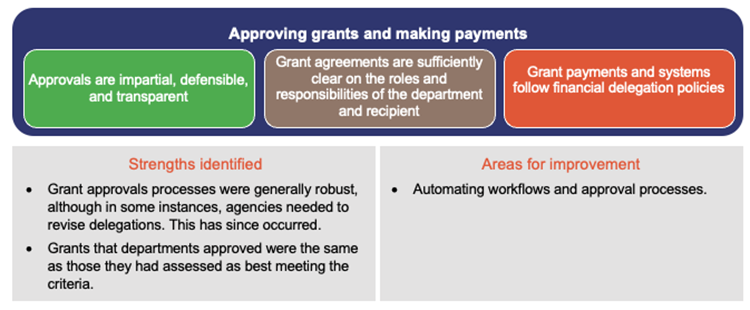

Approving grants and making payments

The approval process releases public monies to grant recipients. Appropriate controls must be in place to ensure an authorised financial delegate makes the payment for the right reasons and the purposes for which it was intended.

Figure 3E shows the strengths and the areas for improvement we identified in the grant approval process across the 8 grant programs we assessed.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office from our maturity model assessment of 8 grant programs.

We found all of the grants we reviewed were awarded in line with agencies’ assessment of who best met the criteria.

In a previous report – Awarding of sports grants (Report 6: 2020–21) – we discussed the role of the minister in the grant process. Since then, we have found that other agencies also had some confusion about this role, so we have briefly discussed it here.

Recognising the role of the minister in grants

The Financial Accountability Act 2009 and Queensland Treasury’s Financial Accountability Handbook require financial approval to rest with the director-general of a department or their delegate (a public service employee).

In our report, Awarding of sports grants (Report 6: 2020–21), we explained the minister’s role in the grant process. In brief, the minister may be involved in starting a grant program, giving feedback on the design of the program, and ensuring the department’s operations are aligned with government policy. However, all grants require financial approval from the director-general or their delegate.

Following our report, all departments reviewed their financial delegations. A small number identified that ministers had been incorrectly granted a financial delegation to approve payments. These delegations have since been revised.

Using automation for recording and approving grants

Across the grant programs we assessed, 4 different information technology systems were used for grants management, and one program used a spreadsheet. One system, that was used for 3 programs, did not interface with the finance system, so grants needed to be entered and approved separately in the finance system. This lack of automation results in duplication of processes. It also increases the risk that incorrect grant payments will be made.

Three of the departments used grants management systems that allowed for approval and payment of grants. These systems only allowed employees with the correct delegation to approve grants. This is a much more efficient process, with less risk of error. Other departments have since been moving to more automation in their grant recording and approval processes.

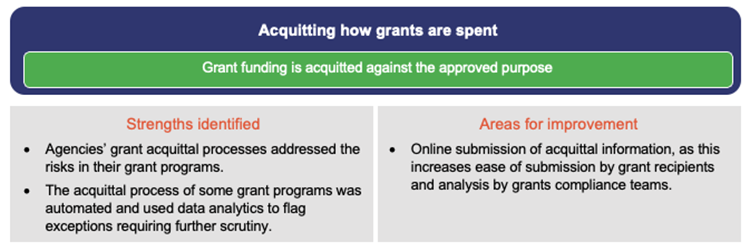

Acquitting how grants are spent

Grant acquittals are the mechanism by which recipients:

- provide evidence that they have used grant funds appropriately

- report on the key milestones and objectives they have achieved.

Figure 3F shows the strengths and the areas for improvement we identified in the grant acquittal process across the 8 grant programs we assessed.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office from our maturity model assessment of 8 grant programs.

Acquittal processes addressed the risks in grant programs

Acquittal processes should reflect the risks associated with a grant program. For example, a grant to construct a specific asset by a specified date is likely to need a regular acquittal process to provide updates on progress and milestones. However, a grant for financial support during an extreme event like a pandemic may be used for broad purposes (for example, for business operating expenses), so extensive acquittal processes might not be needed.

To achieve appropriate accountability, the following aspects should be considered when designing a grant acquittal process:

|

Compliance |

The size and complexity of the grant will determine the extent of information required to ensure milestones have been achieved and funding has been used appropriately, in accordance with the grant agreement. |

|

Performance |

How individual grant recipients will contribute to the overall objectives of the grant program will inform the nature of the information required to be provided. |

|

Timeliness |

The timing of grant activity and payments will determine how frequently information needs to be provided. Regular monitoring ensures grant delivery remains in line with the grant agreement. It allows the department to take timely remedial action when required, before any further payments are made. |

|

Cost |

The cost to the recipient of providing this information, as well as the cost to the department in monitoring this information, must be understood and balanced with the outcomes intended to be achieved from the grant, the risks identified, and the degree of accountability required. Where possible, existing reporting or standardised templates with online functionality should be used to minimise costs. |

Poorly designed acquittal processes can be costly for grant recipients to comply with and department employees to administer. For smaller grants, the cost can outweigh the benefit.

The grant programs we assessed balanced the size and risk of the program with the extent of acquittal reporting required to be provided by recipients.

Our experience with other grant programs indicates this is not always the case. This can result in a lack of evidence being obtained to confirm compliance with the grant agreement before making further payments, or in contract variations to extend milestones and reporting deadlines – both of which should be avoided.

Agencies could automate their monitoring of grant funding more

We found grant acquittal processes varied significantly – ranging from detailed checking of extensive reports to having highly automated processes with analytics used to flag exceptions for further investigation by a specific compliance team.

Two of the 5 departments had very manual processes for following up outstanding acquittals and checking them once they had been received. This is very costly and time consuming, and can prevent an agency from acting early to identify and address potential problems in the delivery of a grant program.

Acquittals that were able to be submitted online by applicants were generally complete and provided on time. They were also more easily monitored and analysed for exceptions by agencies. This represents the biggest opportunity for government to invest in processes that over time will be more efficient and therefore less costly, while achieving improved outcomes from grant funding.

|

Recommendation 7 All departments should enhance the acquittal of grants |

|

We recommend all departments enhance the acquittal of grants by:

|

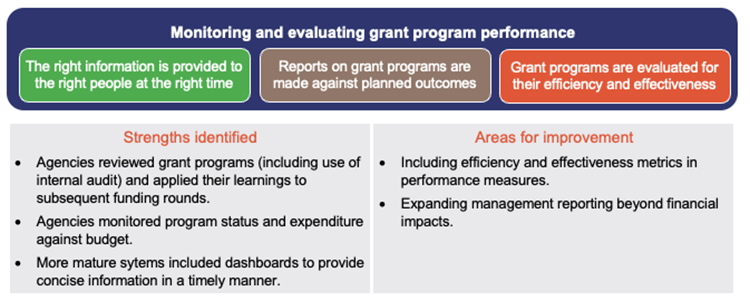

Monitoring and evaluating grant program performance

Grants management teams provide reports to management to allow them to assess the progress and effectiveness of grant programs, and determine whether outcomes and milestones are being achieved in line with the grant agreements.

Post-implementation evaluations of grant programs provide an opportunity to build on what worked well and to improve benefits and value-for-money outcomes in future. Queensland Treasury’s Queensland Government Program Evaluation Guidelines provide the following examples of evaluation questions:

- To what extent was the program effective in achieving intended outcomes?

- To what extent can outcomes be uniquely attributed to the program?

- Do outcomes represent value for money?

- How equitably and efficiently were benefits distributed among stakeholders?

Figure 3G shows the strengths and the areas for improvement we identified in the grant reporting and evaluation process across the 8 grant programs we assessed.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office from our maturity model assessment of 8 grant programs.

Reviews of programs have been performed, but learnings have not been shared

Three of the programs we assessed as having an average overall rating of ‘integrated’ had been reviewed by internal audit, and the agencies that administer them had taken action to implement the recommendations made. In doing so, they strengthened the grants management processes they used for future funding rounds.

This is an advantage of grant programs that operate over a longer period, as they are able to continuously improve the efficiency and effectiveness of their processes. But learnings from these reviews could be better shared. Even within these agencies, the recommendations have not been widely shared and adopted across the other grant programs they manage.

Performance measurement and reporting could be more robust

All grant programs used a range of metrics (such as applicant numbers, budget spent, or the number of jobs created) to measure their performance. However, in some instances, the performance information was limited and did not objectively assess the efficiency and effectiveness of the performance of the grant program. Instead, there was a heavy emphasis on monitoring the number of grants paid, or budget spent to date. These are activity measures that provide basic information about a department’s delivery of a grant program, but not on its performance, the performance of the recipient, or the grant program outcomes.

Reports were provided regularly to decision-makers, and some departments used dashboards to provide concise and timely information. But most grant programs did not have measures to help them monitor the progress made towards their targets on a regular basis. This means departments would only know if the milestone deliverables and objectives of the grant were not going to be achieved when it was too late.

A lack of strong key performance measures reflects weaknesses in establishing grant programs. The measures need to be clearly outlined before the program starts. Otherwise, it can be difficult to objectively assess performance at the end.

Improved performance monitoring could enable benchmarking of similar programs across government. This could provide more and better information for decisions about funding allocations and whether programs should be discontinued or modified.

All agencies have established efficiency targets in their service delivery statements (which provide financial and non-financial information for the annual state budget). However, only some agencies have a specific efficiency measure for grants management due to the important role grants play in their delivery of services.

For example, in 2020–21, the Department of Employment, Small Business and Training introduced a consistent efficiency measure for employment and small business service areas, with respective targets of $103.80 and $130.60 administrative cost per $1,000 of program support. Other agencies could consider a similar measure with large grant programs.

|

Recommendation 8 All departments with significant grant programs should develop and implement stronger key performance measures to better monitor grant program performance and outcomes |

|

We recommend all departments with significant grant programs ensure they develop and periodically monitor key performance metrics to measure:

For similar programs across government, consistent performance metrics should be developed, to enable benchmarking across government. This will support ongoing improvements in the efficiency and effectiveness of grant programs. |

Understanding grants dashboard

Our interactive dashboard allows you to explore and compare information on grants, compare councils and funding agencies, and access information relevant to understanding the local context for specific grants.