Overview

Most of Queensland's coal seam gas activity occurs in the state's agricultural regions. As both the coal seam gas and agriculture industries are important to the state's economy, it is essential that the coal seam gas industry is effectively regulated to ensure the different industries, landholders, and communities involved coexist, the benefits are maximised, and the risks managed. Tabled 18 February 2020.

Report on a page

We audited two regulators, the Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy (DNRME) and the Department of Environment and Science (DES). We also audited the GasFields Commission Queensland (the commission). The commission is not a regulator, but it has a legislated oversight role to the regulatory framework, facilitates coexistence and provides advice to government, industry and stakeholders. We highlighted the performance of the regulators and the commission in fulfilling these roles, the gains they have made, and their ongoing challenges, in delivering on the government’s coexistence policy (meaning landholders, communities and industry successfully existing together).

Regulatory framework

Dispersing regulatory responsibility across DNRME and DES has the benefit of drawing on their specific expertise but necessitates effective strategic planning, coordination and reporting between them.

The regulators could enhance their current regulatory practices by better coordinating their planning, information and data sharing. Work units within and across the regulators use different systems to support their work. The lack of system interoperability (when systems can exchange data and interpret that shared data) makes it difficult for the regulators to collectively coordinate and report on regulatory activities. Greater collective oversight and reporting on compliance and enforcement outcomes would enhance stakeholder confidence in the regulators and the government’s coexistence approach.

The use of data to better identify and target emergent risks will allow for a proactive approach to regulating the industry. This will enhance the effectiveness of the regulatory activities and aid in improving community confidence.

The commission is not fulfilling all of its legislative functions. It does not provide oversight of the regulatory framework.

Stakeholder management and engagement

The regulators and the commission partner with one another to engage stakeholders. Their efforts have improved relationships between industry, regulators and landholders in recent years. However, some stakeholders still perceive the commission as an advocate for the industry. We recommend evaluating the current engagement approach to determine its effectiveness in meeting the needs of all stakeholders.

Community concerns

Some landholders say they have been unable to obtain information relevant to their land from the two regulators and from industry. They state that the cost of obtaining independent information and advice is high and they are unable to get the same level of information that industry has. This puts them at a disadvantage when negotiating with industry—for example, when negotiating conduct and compensation agreements. To coexist effectively, landholders and the community need confidence that the industry's behaviour is transparent, and that government will hold all participants (including industry and regulators) accountable.

We have made recommendations to the regulators to work together to improve their use of data, reporting, information sharing and stakeholder engagement.

Introduction

Commercial production of coal seam gas in Australia began in 1996 in the Bowen Basin of Queensland. Growth in coal seam gas activities has grown rapidly since then to 11,444 coal seam gas wells in Queensland at the end of the 2018–19 financial year.

Coal seam gas is natural gas (mostly methane) sourced from coal deposits (coal seams), which are typically 400 to 1,000 metres underground. These coal seams sit far below shallow aquifers, which provide water for agricultural use. Wells the size of a dinner plate are drilled into the coal seams, releasing water and gas. The water is pumped to holding dams and may be treated to be used for agriculture or other uses. The gas is pumped to a processing facility to be compressed and fed into gas transmission pipelines. It can be used to generate electricity. It can also be cooled, liquified and shipped as liquified natural gas to markets.

In the 12 months to April 2019, liquefied natural gas was Queensland’s second greatest export commodity, with a total export value of $15.2 billion.

The rapid growth of the coal seam gas industry has led to public concerns about impacts on the community, agriculture, health, and the environment. Some of the concerns relate to the effect of the industry on:

- ground water

- land access and land values

- agricultural produce

- the environment (for example, the long-term management of safe disposal of salt and brine waste)

- uncontrolled or unintended release of gas (referred to as fugitive emissions).

As a result of similar concerns, New South Wales, South Australia, Tasmania, Victoria and Western Australia have placed either complete or partial bans on coal seam gas activity. (See Appendix D.)

The Queensland Government has a framework focused on promoting the coexistence of landholders, regional communities, and industry. The primary focus of the land release framework is for development of the state’s petroleum resources that maximise benefits for Queenslanders, including an adequate return to the state for its mineral resources and ensuring future gas supply. Potential exclusions and regulatory constraints are considered before releasing land for coal seam gas activities.

A significant amount of Queensland’s coal seam gas resources is found in the state’s agricultural regions, including in some of the most productive agricultural land. The two industries compete with one another for land use. The Queensland Government’s coexistence framework aims to balance the importance to the state of both coal seam gas and agriculture. Coal seam gas contributes to the nation’s energy needs and agriculture is vital for the nation’s food security. Both contribute to the economy through substantial exports.

Effective government regulation is essential to maintaining coexistence between the two industries. Landholders and communities need a high level of trust in the effectiveness and openness of government regulation. This audit examines the effectiveness of the regulators in regulating the coal seam gas industry.

Regulating the industry

How the industry is regulated

Regulation of the coal seam gas industry is spread across various state government entities. The current regulation considers coal seam gas activities as part of the petroleum and gas industry.

The Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy (DNRME) is responsible for:

- identifying land for release and calling for tenders

- managing the tendering and assessment process for issuing the authorities to prospect and the petroleum leases to conduct coal seam gas activities

- making recommendations to the minister to grant the authorities to prospect and petroleum leases to companies

- ensuring holders of the authorities to prospect and petroleum leases comply with the requirements of their authorities or leases, including production, safety, compliance and decommissioning requirements.

DNRME conducts these activities under various Acts of parliament, including the Petroleum Act 1923, the Petroleum and Gas (Production and Safety) Act 2004, the Mineral Resources Act 1989 and the Mineral and Energy Resources (Common Provisions) Act 2014.

The Office of Groundwater Impact Assessment administratively sits within DNRME. It has responsibility and technical expertise for assessing and managing the impacts of groundwater extraction in cumulative management areas.

The Department of Environment and Science (DES) is responsible for approving, monitoring and regulating environmental authorities and conditions for companies to undertake coal seam gas activities.

It conducts its activities primarily under the Environment Protection Act 1994, and the Environmental Protection Regulation 2008.

The Queensland Government set up the GasFields Commission Queensland (the commission) in 2012 to manage and improve the sustainable coexistence of landholders, regional communities and the onshore gas industry in Queensland.

The commission conducts its activities under the Gasfields Commission Act 2013 and its legislation gives it 14 functions to achieve its objectives. Its functions can be grouped into three categories: overseeing the regulatory framework; facilitating coexistence; and advising government, industry and stakeholders. Appendix E lists all 14 legislated functions.

Other Queensland Government departments and entities, such as the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, and the Department of State Development, Manufacturing, Infrastructure and Planning, have specific functions supporting aspects of the regulation of the industry.

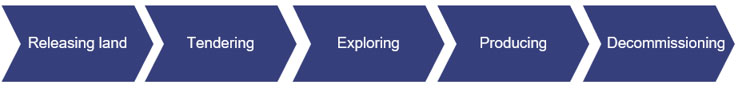

Figure A shows the phases of coal seam gas activities and Appendix C provides more detail.

Queensland Audit Office.

Summary of audit findings

Regulating the industry

The Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy (DNRME) and the Department of Environment and Science (DES) (we refer to these agencies collectively as the regulators) have clear roles and responsibilities in the regulatory framework. Each regulator sets up adequate processes to manage activities that are relevant to its own regulatory functions. The regulatory framework applies across a range of industries and the regulators manage coal seam gas as part of this (it is not specific to coal seam gas). They do not identify coal seam gas activities separately from their other regulatory activities, do not coordinate their planning and regulatory activities, and have disparate systems and data practices. These limitations make it difficult to assess the overall effectiveness of the regulatory framework specific to coal seam gas activities.

Compliance planning

Each year, the regulators plan their compliance audit and inspection activities for the coming year. To varying degrees, the regulators adopt a risk-based planning approach, which in most cases includes operator and site risks. This is good practice as it allows the regulators to target their resources most effectively to the areas they consider to be highest risk. Nevertheless, they could enhance their risk-based planning by including industry-specific risks.

Their planning tends to cover the broad range of regulations and industries they regulate, and they tend not to have coal seam gas‑specific activities in the plans. This makes it difficult for them to adequately focus on or target coal seam gas‑specific risks. In their plans, we expected to see them identify the key industry risks they planned to target and the outcomes they intended to achieve. We found some examples of this occurring, but it was not widespread. For example, DNRME’s Petroleum and Gas Inspectorate undertook a specific compliance assessment project of audits and inspections of wells for statutory compliance.

The regulators’ plans could also be improved by better detailing the outcomes they are seeking rather than measuring activities. For example, some plans only list how many inspections have been done in a resource company, but they do not list the type of risks the activities aimed to address.

Monitoring compliance

The regulators monitor compliance through the planned audits and inspections they undertake and through reactive audits and inspections when they receive complaints from the community or notifications of incidents from industry.

DES focuses on compliance areas relating to environmental authorities whereas DNRME focuses on areas relating to tenure conditions and workplace health and safety. The regulators have developed an effective process for monitoring coal seam gas activities within their regulatory functions. However, the regulators record compliance outcomes in different databases. DES's data cannot differentiate whether the identified locations are coal seam gas‑specific as its datasets do not identify coal seam gas-specific activity. DNRME has similar issues. This limits the ability to build a collective picture of how well the regulators monitor compliance in the coal seam gas industry.

Education and enforcement

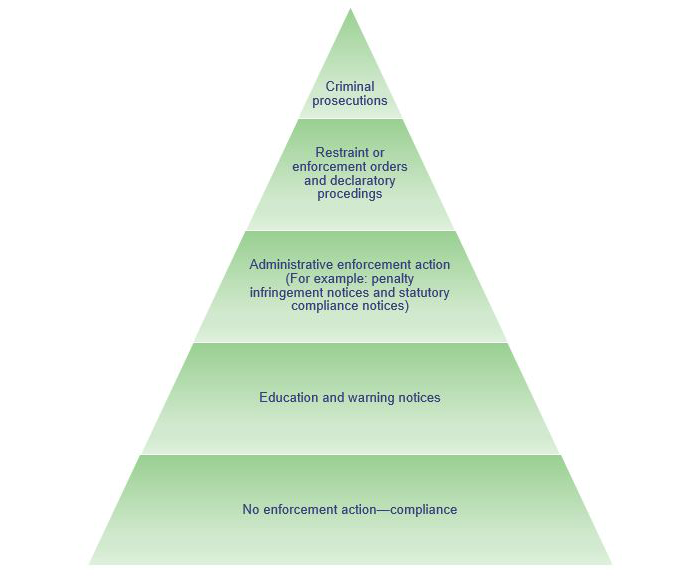

Both DNRME and DES have, and are increasingly using, a range of education and enforcement options when they identify non-compliance with tenure or environmental conditions. They both adopt an approach of working to bring non-compliant operators into compliance. When they detect non-compliance, the regulators initially work with operators to educate and guide them into returning to compliance. For this reason, their use of enforcement action has, to date, been limited. Where non-compliance persists, they adopt more formal enforcement methods. There is evidence that they act to enforce compliance, such as issuing infringement notices, prosecution and, in one case, cancelling tenure.

Reporting and coal seam gas data

The regulators currently report on activities and status rather than on outcomes. The regulators do not monitor or report on how effectively they enforce compliance of the coal seam gas industry. DNRME does not track and report the number of operators who were found to be non‑compliant but were subsequently brought back into compliance. DES does track and report on this at an aggregate level, but it does so collectively for all industries it regulates. It, therefore, does not know and cannot report on how effectively it enforces the coal seam gas industry.

The regulators have limited data sharing capabilities. This reduces their effectiveness in monitoring all phases of coal seam gas activities (see Figure A in the introduction). As a result, the regulators cannot provide government with a collective understanding of regulatory effectiveness and industry compliance.

Assessing regulator performance in applying the regulatory framework to the tendering, approval, monitoring and enforcement of coal seam gas activities is difficult. This is because the regulators capture regulatory information for the petroleum and gas industries, which includes but is not limited to the coal seam gas industry. This aligns with the guiding legislation. Because the regulators do not categorise within their information to distinguish coal seam gas from other petroleum and gas leases or authorities, they cannot isolate coal seam gas activities. Doing so requires departmental staff to manually extract and manipulate data and apply assumptions. Consequently, we and the regulators were unable to verify the complete population of authorities and leases for coal seam gas activities with any degree of confidence.

Engaging and managing stakeholders

The regulators and the commission have developed a partnership approach, such as chairing information sessions together, to collectively engage with industry and landholders and promote coexistence. They seek written feedback from participants for some of the engagement sessions. However, they have yet to evaluate the overall approach to assess how well they are collectively meeting the stakeholders’ needs.

Some stakeholders are confused and frustrated by the number of entities (including the regulators, the commission, the Land Access Ombudsman, and other government departments) that perform roles and provide information about coal seam gas activities and processes. Some stakeholders are also confused about the rights, entitlements, and obligations of industry and stakeholders. It is difficult for some landholders to know who to ask for, and how to access, information relevant to their queries or concerns. It also leads to the risk of incomplete or conflicting information being provided on occasion.

Even though landholders can request information from industry, some landholders and representatives reported to us an imbalance in the information they have access to when negotiating with industry. For example, industry and government can access assessments and baseline data. In some cases, they may not share the information with landholders, as industry considers it to be commercially sensitive. This has the potential to disadvantage landholders in negotiations—such as negotiations for conduct and compensation agreements.

Identifying coal seam gas risks

An area of importance to coexistence is effectively assessing the potential impact of resource activities (including coal seam gas) and development activities on highly productive agricultural land. The legislative framework is intended to manage the impact of resource activities and other regulated activities on areas of regional interest by adding additional conditions into approvals to protect these areas. It requires input and recommendations from relevant government departments. The current framework for approving coal seam gas activities on highly productive agricultural land requires collaboration between four departments: the Department of State Development, Manufacturing, Infrastructure and Planning; the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries; DNRME; and DES. Stakeholders have separately raised the need for greater consistency of land classifications across the legislation and the need to improve the identification of priority agricultural interests and protect them from non-agricultural development. Although not within the scope of this audit, stakeholders also raised concerns that the current framework has not kept pace with new types of activities (for example, use of priority agricultural land for solar farms is not subject to this framework). There is an opportunity to evaluate the effectiveness of the current framework to ensure it continues to meet the intent of the government’s coexistence policy.

People who live near a coal seam gas site may be impacted by the activities (referred to as offsite impacts). In April 2018, the Queensland Parliament’s State Development, Natural Resources and Agricultural Industry Development Committee (the parliamentary committee) reported on its review of the Mineral, Water and Other Legislation Bill. The parliamentary committee, while noting it was outside the scope of its review of the Mineral, Water and Other Legislation Bill, expressed concern at the adequacy of the legislative framework to remedy or compensate people for offsite impacts. Landholders and their representatives continue to express concern that they have struggled to obtain remedy and/or compensation for offsite impacts. More than 18 months on from the parliamentary committee expressing its concerns, it is now timely for DNRME, DES and the commission to evaluate the effectiveness of the ‘alternative arrangements’ to provide adequate rights to people affected by offsite impacts.

The regulators and the commission have not developed an approach to effectively identify risks using the coal seam gas data they gather. For example, the regulators only conducted limited strategic analysis to build a collective understanding of industry trends. In recognising the need for better business analytics capability, the regulators have started projects to modernise the way they capture and use data to better inform their regulatory activities.

Oversight of the regulatory framework

The commission has 14 legislative functions (see Appendix E), one of which is to review the effectiveness of government entities in implementing regulatory frameworks that relate to the onshore gas industry.

Changes to the regulatory frameworks (with the introduction of the Land Access Ombudsman and role of the Land Court), ongoing perceptions about the independence of the commission, and the industry maturing since the commission’s establishment, create an opportunity for government to consider the commission’s scope and future role.

Audit conclusions

The viability of the coal seam gas industry depends on its ability to coexist with landholders and regional communities. The industry has matured and is now more viable because DNRME and DES (the regulators), GasFields Commission Queensland (the commission) and companies have invested in their relationships with landholders and communities. Some underlying tensions remain, and relationships require ongoing fostering, particularly as new areas are made available for coal seam gas exploration and production.

The regulators have developed an effective framework for approving, monitoring and regulating coal seam gas activities, environmental obligations, and safety within the legislation they operate. However, we and the regulators were unable to verify the complete population of authorities and leases for coal seam gas activities with any degree of confidence. DNRME operates based on industry groupings, which includes coal seam gas as a subset of the petroleum and gas industry. Based on the testing we have performed, we did not find any non‑compliance with their processes. However, because we are unable to establish the complete population, we can only provide limited assurance over their effectiveness in regulating the industry to ensure a safe industry that is compliant with tenure and environmental obligations.

Concerns from landholders and other stakeholders persist regarding the effectiveness of the framework in managing issues such as priority agricultural areas, offsite impacts, and the long‑term environmental effects of coal seam gas activities. The regulators need to continue to refine their engagement and regulatory processes, procedures, and systems in response to concerns and the changing environment.

The regulators are now starting to more readily apply the full suite of compliance and enforcement options available to them. However, the regulators’ current systems limit their ability to provide an overall view of the collective effectiveness of their regulatory activities and limit their ability to share information and coordinate activities. The regulators could enhance their current regulatory practices by better coordinating their compliance planning, and information and data sharing.

The coal seam gas landscape has changed since the commission was established in 2012 and the Independent Review of the Gasfields Commission Queensland in 2016 (the Scott review). It continues to evolve. It is timely for government to consider the effectiveness of the commission in delivering value, particularly considering it is not fulfilling all its legislated functions and stakeholders question its effectiveness and independence.

The coal seam gas industry expanded rapidly over the past 10 years. The regulators have needed to adapt to this expansion and the emerging body of science and information about the industry. For the government’s coexistence policy to be successful, the regulators and the commission must continue to adapt as unresolved concerns persist, new issues emerge, and the science continues to evolve. This ongoing evolution of the industry will require government to continually evaluate and refine its regulatory framework.

Recommendations

The Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy and the Department of Environment and Science

We recommend the two entities:

1. make better use of their data to effectively deliver regulatory outcomes (Chapter 1), by:

- collecting and analysing data from across the regulators and the industry to identify current and emerging coal seam gas risks, trends and priorities

- using insights from the data analysis to inform their compliance planning and engagement across all areas of the departments

- training and supporting staff in further analysis and use of data to better target compliance activities

- improving their reporting to develop a collective understanding of industry compliance and regulatory outcomes

2. enhance coordination between the departments to assist in providing greater clarity for applicants and stakeholders on the progress of tenure and environmental authority applications (Chapter 1).

The Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy, the Department of Environment and Science, and the GasFields Commission Queensland

We recommend the three entities:

3. develop and implement a coordinated data sharing framework for sharing information relating to their regulatory activities (Chapter 1)

This should include:

- establishing systems and processes (and automation, to the extent possible) to improve their ability to use the data

- agreeing on data requirements and a common identifier for coal seam gas related activities to better facilitate the exchange of information between the entities.

4. work with key stakeholders to further evaluate the adequacy of remedy for property owners neighbouring coal seam gas activities (Chapter 1)

5. evaluate their current collaborative engagement approach to determine its effectiveness and how they can better address the needs and concerns of stakeholders (Chapter 2)

6. facilitate ways to further enhance the exchange of information between industry, government and landholders in situations where landholders have not been given the information to make an informed decision. This should consider potential legislative changes and commercial-in-confidence constraints (Chapter 2).

The Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy

We recommend the department:

7. publishes the weighting and any mandatory criteria used for assessing or excluding tender applications (Chapter 1).

The GasFields Commission Queensland

We recommend the commission:

8. reviews the assessment process identified under the Regional Planning Interests Act 2014 to determine whether the process adequately manages coal seam gas activities in areas of regional interest. This should take into consideration stakeholders’ concerns about inconsistent definitions of land and exceptions to the assessment process (Chapter 1).

The Department of State Development, Manufacturing, Infrastructure and Planning

We recommend the Department of State Development, Manufacturing, Infrastructure and Planning:

9. determines the scope, future function and role of the GasFields Commission Queensland, taking into consideration industry maturity and consultation with the commission, regulators and industry (Chapter 2).

1. Regulating the industry

This chapter covers the effectiveness and efficiency of public sector entities in regulating the coal seam gas industry to ensure a safe and viable industry.

Introduction

Coal seam gas extraction can provide economic benefits to landholders and local communities, including access to treated groundwater for the agricultural industry. It also creates challenges for industry, for example managing waste products such as salt and brine, which are produced in the extraction process. When it affects areas surrounding the coal seam gas site, such as neighbouring farms, the effect is referred to as offsite impacts.

Effective regulation of coal seam gas activities is essential to ensure the industries, landholders, and communities coexist, the benefits are maximised, and the risks managed.

We expected to find the regulators to have effective planning, monitoring and enforcement frameworks in place. An effective compliance monitoring plan should lay out how compliance will be monitored. The plan should be based on a risk assessment and include inspection strategies (for example, coverage of the industry or frequency of inspections) and information requirements (for example, documents submitted by the regulated population).

We examined whether the Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy and the Department of Environment and Science (the regulators):

- are clear about their roles and responsibilities in the devolved regulatory environment

- follow legislative processes to release land for tendering

- have designed and applied appropriate processes for approving applications in accordance with required legislation/policies/guidelines

- use data to effectively plan and monitor their regulatory activities on a risk basis to maximise compliance effectiveness

- have an appropriate range of enforcement actions and apply them in appropriate circumstances

- ensure wells are appropriately decommissioned.

Releasing land for coal seam gas activities

Governments decide what land they will release for coal seam gas activities. Industry can then submit tenders for the right to explore and mine on the released land.

The Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy (DNRME) is responsible for managing the release of land for tender under Queensland’s exploration program. The Queensland Government’s framework for releasing land focuses on landholders and industry successfully existing together (coexistence).

DNRME considers potential exclusions and regulatory constraints before releasing land for coal seam gas, but the primary focus of the framework is on releasing land and managing the risks. Coal seam gas companies tendering for land would consider factors such as its commercial potential (production) and any environment and lease conditions set by the regulators.

DNRME’s process and guidance for managing the tendering of land is adequate to meet the intent of the government’s framework, but its consultation on releasing land and its assessment of tenders against evaluation criteria could be refined.

Consulting on release of land

DNRME develops an engagement plan for Queensland’s exploration program to engage with stakeholders (communities and industry groups, such as the Queensland Farmers Federation) on exploration areas to be released for tender over the upcoming 18 months. Some stakeholders commented to us that the consultation seemed to be more of a notification than a meaningful consultation. This may be due to the timing of the consultation. For stakeholders to feel that consultation is meaningful, it needs to occur at a time when they can influence the outcome.

DNRME previously consulted with relevant public sector entities when it considered releasing certain types of land. Between 2014 and 2016, DNRME sought advice and recommendations from the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries (DAF) on the proposed release for tender of land identified as priority agricultural areas and strategic cropping land. Consulting with DAF was appropriate to ensure the interests of the agriculture industry were considered when making these decisions. However, from 2016 to late 2019, DAF did not receive any requests for advice or recommendations from DNRME. DNRME advised us that it did not make an explicit decision to stop, and that it is now considering re-engaging with DAF for advice on releasing agricultural land before finalising future exploration programs.

The tendering process

DNRME’s processes and guidance about tendering for land include (but are not limited to) probity requirements, evaluation criteria, separation of roles, and approval and review mechanisms. However, the department’s weightings against the evaluation criteria could better reflect landholder and community concerns, which predominately relate to health and the environment.

The criteria used by the department to evaluate tenders comply with the criteria for decisions specified in section 43 of the Petroleum and Gas (Production and Safety) Act 2004:

- capability criteria—financial and technical resources; ability to manage petroleum production

- applicants proposed initial work program

- any special criteria.

The Petroleum and Gas (Production and Safety) Act 2004, does not define ‘special criteria’ and does not place a weighting on the three criteria categories. The department’s template for assessing these criteria lists three sub-categories of special criteria. (See Figure 1A). DNRME weights the criteria to prioritise economic benefits over health and safety, environmental concerns, legislative requirements, and native title consultation and compliance (Special Criteria 2). The department previously disclosed its weighting for the criteria but ceased this practice in recent years. Disclosing to applicants the basis on which the department will assess them against the criteria (including any weightings or other considerations) would be a good practice, as it would provide greater transparency to applicants. The department advised us that it is considering disclosing its weighting of assessment criteria for future tender releases.

| Criteria | Description |

|---|---|

| Capability | Financial and technical resources; ability to manage petroleum production. |

| Initial Work Program | Appropriateness of tenderer’s proposed work program. |

| Special Criteria 1 | Ability to contribute to a diverse and efficient exploration industry in Queensland. |

| Special Criteria 2 | Ability to meet Australian market supply conditions and supply gas to the Australian manufacturing sector. |

| Special Criteria 3 | Approach to community consultation and compliance with relevant Queensland resources legislation, environmental requirements, health and safety requirements, cultural heritage requirements and native title. |

Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy, Call for tenders for authority to prospect evaluation plan template.

Collectively, the department places a higher weighting on diversity and efficiency (Special Criteria 1), technical/financial capability and work program (Capability Criteria and Initial Work Program), and, where it applies, domestic market supply (Special Criteria 2). It places a lesser weighing on health and safety, environmental concerns, legislative requirements, and native title consultation and compliance (Special Criteria 3). The department should reconsider whether these weightings adequately align with the government’s policy of coexistence.

Approving coal seam gas activities and setting conditions

The regulators have adequate processes and guidance in place to assess and approve applications for coal seam gas exploration, production and associated environmental impacts. Elements of the regulators’ processes rely on collaboration and coordination between the departments; this does occur, but could be improved.

The regulators could make their processes more efficient and effective by better coordinating their efforts and sharing information. They could also introduce benchmark time frames for parts of the assessment process, recognising that applications may vary in complexity. This would provide a higher degree of clarity to industry and landholders and allow the regulators to better track performance of the approval process.

Industry has suggested a coordinator be appointed for each application to coordinate the assessment between regulators, improve timeliness, and reduce duplication. A more client‑centric approach and better coordination between the departments could assist in providing greater clarity for applicants on the progress of their applications.

Assessing applications

To conduct coal seam gas activities, companies must apply for, and be assessed as suitable by:

- DNRME to hold an authority to prospect or a petroleum lease

- Department of Environment and Science (DES) for an environmental authority.

Where appropriate, DES will consult with the Office of Groundwater Impact Assessment for technical advice.

The two departments’ assessment processes are conducted in parallel as they are interdependent—an authority to prospect or a production lease cannot be granted without an environmental authority also being granted.

Authorities to prospect and petroleum leases

DNRME has developed an adequate three-staged business process for assessing applications:

- application lodgement and verification

- assessment

- decision.

The process is supported by policies, templates, checklists and flow diagrams to guide staff in consistently applying the process and understanding their roles and responsibilities. This material references relevant statutory requirements.

Between 1 July 2013 and 30 June 2019, DNRME granted 32 authorities to prospect and 41 petroleum leases. Most companies were granted multiple authorities over different sites.

Assessing applications for environmental authorities

DES has developed an adequate business process for assessing applications and setting appropriate environmental conditions. Its process is detailed in its guideline, Application requirements for petroleum activities. The process is supported by policies, templates and checklists to guide applicants and staff in consistently applying the process and understanding their roles and responsibilities. This material references relevant statutory requirements. The process is designed to cater for three types of environmental authorities, which are determined by the specifics (extent and risk of environmental disturbance) of the proposed activity:

- standard—environmental authority with standard conditions. This type of environmental authority is for sites considered low risk and therefore subject to standard conditions

- variation—environmental authority with a variation to the standard conditions. This type of environmental authority is for where the applicant is seeking a variation to the standard conditions

- site specific—environmental authority with conditions that are specific to the site.

The applicant determines the type of environmental authority required for its site. DES approves the standard applications automatically. Its assessment is progressively greater for activities that involve variations to standard condition or site-specific application types.

All petroleum leases require a site-specific environmental authority, which means they are subject to environmental conditions that are tailored to the individual project.

DES is applying its process as intended, however as most applications for environmental authorities are standard, they are granted with limited assessment from DES.

Between 2013–14 and 2018–19, DES processed 94 environmental authority applications relating to coal seam gas activities, of which:

- 70 were for authorities with standard conditions and required only administrative DES assessment before it granted approval

- one was for an authority with a variation to standard conditions

- 23 were for authorities with site-specific conditions.

During this period, DES did not refuse any applications for environmental authorities. It worked with applicants to determine whether activity restrictions were required to prevent and mitigate environmental harm. In those cases where an application did not meet the standard environmental authority conditions, the department worked with the applicant to develop an environmental authority with a variation or with site‑specific conditions.

Timeliness of approving authorities and leases

The time needed to assess an authority or lease application varies depending on the:

- scale and technical complexity of the proposed coal seam gas activity

- specifics of the location (for example whether it is on or close to environmentally sensitive areas)

- responsiveness of the applicant and stakeholders in responding and providing information to the departments.

The Petroleum and Gas (Production and Safety) Act 2004 sets time frames for resource holders to lodge applications. For example, the holder must lodge a proposed development plan to DNRME at least 40, but no more than 100, business days before the end of the plan period for its current development plan. The Act does not set decision‑making time frames for tenure approval. DNRME sets its own time frames on the competitive tender process and the tenure application process. For example, the time frame states that it will take between six and 15 months from when a tender is open to when a preferred tenderer is appointed.

The Environmental Protection Act 1994 has set legislative time frames for actioning requests and applications for environmental authorities except for an environmental authority with standard conditions (no assessment required). The time frames vary depending on the type of authority applied for. For example, the legislation states that assessment for an environmental authority with variations to standard conditions is up to 45 days, but for an authority with site‑specific conditions it is up to 90 days. The legislation also allows extension of the statutory time frames.

We assessed the regulators’ timeliness of processing applications against these time frames and we assessed trends in the timeliness of processing applications.

Timeliness of the Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy—tenure

DNRME generally processes petroleum and gas (which includes coal seam gas) applications for tenure on time when assessed against the time frames it sets for itself. It based its time frames on its previous approval performance and the work unit’s assessment of how long an application should take. DNRME is continuing to refine and further develop its benchmark time frames and processes for monitoring its timeliness.

At present, its data and systems are not structured in a way that allows it to distinguish the parts of the approval process it controls from those it does not (such as waiting on native title assessments or waiting for the applicant to provide requested supporting information or assessments). The coal seam gas sector and its representatives expressed concerns about unpredictable decision-making time frames, which they say limit their ability to execute an efficient project schedule. While timely processing of applications can be a measure of efficiency, it must be balanced against the need for effective and robust assessments.

Tendering

Between 2015–16 and 2018–19, DNRME processed 68 per cent of tenders within its own set time frames. The median time DNRME took to process from when a tender was open to when it was offered to a preferred tenderer was 253 days. The department set an indicative time frame of 450 days (15 months). The time it took to assess and process tenders decreased from a median time of 581 days in 2015–16 to 207 days in 2017–18.

Applying for tenure

DNRME is unable to isolate coal seam gas tenures from the applications because the database is set up as per the Petroleum and Gas (Production and Safety) Act 2004. It therefore records authority to prospect and petroleum lease information but does not separate coal seam gas from other petroleum and gas activities.

DNRME is progressively working through a historical backlog of tenure applications. This can skew the calculation of timeliness to process current petroleum and gas authority to prospect and lease applications.

We tried to isolate coal seam gas applications for authorities to prospect and petroleum leases from the petroleum and gas applications recorded in DNRME’s data. Our data shows an improvement in timeliness in the median days for the department processing an authority to prospect—from 200 days in 2013–14 to 110 days in 2018–19. For processing a petroleum lease, it showed the time taken decreased from 341 days in 2013–14 to 196 days in 2018–19. However, we cannot rely on the data due to limitations of the database and assumptions we made to isolate coal seam gas applications.

Timeliness of the Department of Environment and Science—environmental authorities

DES is generally meeting its statutory time frames for assessing and processing environmental authorities. This is largely because most coal seam gas applications are for authorities with standard conditions, which are self-assessed by the applicant.

Between 2013–14 and 2018–19, DES processed applications for environmental authorities with standard conditions with a median of eight days. This was within the department’s benchmark of 10 days. The approval process for environmental authorities with standard conditions is largely administrative, based on the applicant’s self-assessment of their ability to comply with the standard conditions.

The assessment and processing of environmental authorities with variations to standard conditions and for site-specific authorities is more complex and naturally takes longer. Between 2013–14 and 2018–19, DES processed the only application for environmental authority with variations to standard conditions in 26 days. This was within its set statutory time frame. It processed 26 per cent of applications for site‑specific environmental authorities within its set statutory time frame, with a median of 226 days. The legislation allows extension of the statutory time frames.

Overall, the median time it took to assess, and process, environmental authorities increased between 2015 and 2016, from 128 days to 226 days for site-specific environmental authorities. The median time it took to process standard environmental authorities (no assessment is required) decreased from 11.5 days to four days between 2013–14 and 2016–17.

Approving activities in priority agricultural areas and strategic cropping land

The Department of State Development, Manufacturing, Infrastructure and Planning (DSDMIP) is responsible for assessing and approving coal seam gas activities in high‑value agricultural and strategic cropping land. It ensures the activities are complying with the requirements of the Queensland Government framework (consisting of various legislation and the state planning policy) for releasing land for resources activities (including coal seam gas).

Important agricultural areas (IAAs) are comprised of land that meets the conditions required for agriculture to be successful and sustainable. IAAs are part of a critical mass of land with similar characteristics and are strategically significant to their region or state. The state planning policy aims to promote agriculture and agricultural development as the preferred land use in an important agricultural area.

A priority agricultural area is an area of regional interest under the Regional Planning Interests Act 2014. They are strategic areas, identified on a regional scale, that contain significant clusters of the region's high-value intensive agricultural land uses (priority agricultural land uses).

Strategic cropping land is land that is, or is likely to be, highly suitable for cropping because of a combination of the land’s soil, climate and landscape features. The areas of strategic cropping land are, altogether, the ‘strategic cropping area’ under the Regional Planning Interest Act 2014.

The Regional Planning Interests Act 2014 determines whether a ‘regional interests development approval’ for the proposed activity should be issued, and, if so, whether certain conditions should be attached to it to manage potential impacts. The conditions are generated from input and recommendations from relevant government departments. For example, the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries (DAF) is consulted when the activity is proposed on a priority agricultural area.

Case study 1 details the number of applications subject to this process and instances where additional conditions were included in the approval.

| Regional interest development assessments for coal seam gas activities |

|---|

|

Between 2015 and 2019, DSDMIP referred 12 coal seam gas applications to agencies for a regional interest development assessment. The applications related to strategic cropping areas and priority agricultural areas. Ten were finalised and two were withdrawn by the applicant. For the 10 finalised applications, DSDMIP consulted with DAF and the GasFields Commission Queensland. DSDMIP considered the recommendations provided by these agencies and attached conditions to the decision notice. For example, DAF assessed the proposed activity for an application that would ‘have an irreversible impact on the land used for a priority agricultural land use’. It recommended that if the application is approved, it should be conditional on the applicant providing evidence of adequate mitigation strategies, such as the provision of equivalent land to offset the land irreversibly impacted. The applicant subsequently provided such evidence and the application was approved with that condition. |

Queensland Audit Office, using information obtained from the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries and the Department of State Development, Manufacturing, Infrastructure and Planning.

Stakeholders have expressed concerns over the complexity of Queensland’s planning and development framework, including the regulation of resource activities on agricultural land. Specifically, stakeholders are concerned about:

- the inconsistency of land classifications across the different Acts under the framework

- the exemptions and limitations on the requirement for assessments under the framework.

For example, the assessment framework under the Regional Planning Interests Act 2014 regulates a limited range of activities and only applies to ‘areas of regional interest’. DAF is only involved in assessing those applications if the priority agricultural areas are currently used for a priority agricultural land use.

The current classifications of land also limit the regulators’ ability to effectively consider contemporary concerns for these priority lands. Although not within the scope of this audit, stakeholders raised concerns that the current approach has not kept pace with new types of activity (for example, use of high‑quality agricultural land for solar farms is not subject to this framework). The Queensland Farmers Federation and DAF have separately proposed options for providing greater consistency of land classifications across the legislation and improving the identification and protection of agricultural interests from non-agricultural development. To date their proposals have not been adopted.

Planning and monitoring coal seam gas activities

Spreading the regulatory functions across the regulators has benefits in that it draws on specific relevant expertise across the public sector. However, effective planning, coordination and reporting between the regulators is essential.

While a number of these work units are applying good practices and the regulators generally cooperate and work together to regulate the industry, the information is dispersed, and visibility of industry‑specific information is challenging. Consequently, the regulators do not have a collective understanding of the combined scope, efficiency or effectiveness of their coal seam gas regulatory activities.

The regulators could better inform industry of their planned compliance activities. Currently, some discuss the planned activities via industry forums only. There is an opportunity to more broadly inform industry and stakeholders and improve accountability by publishing the information online.

Compliance planning and monitoring

The regulators develop compliance monitoring plans for their activities—such as inspections of coal seam gas sites to check for companies’ adherence to the prescribed conditions. Compliance monitoring plans serve multiple purposes. A good plan maximises regulator efficiency and effectiveness by:

- directing the regulators’ resources and activities to the highest areas of risk for non‑compliance. This is particularly important when regulating a complex and geographically dispersed industry

- informing the industry of the regulators’ intended activities and areas of focus

- showing the areas where enforcement actions are likely to be taken

- deterring non-compliance

- enhancing public confidence that the industry is well regulated.

Figure 1B shows our assessment of the regulators’ compliance plans against a good compliance plan.

| Area of assessment | DES | DNRME |

|---|---|---|

| Does the plan target a high-risk area? | Yes | To some extent |

| Does the plan inform industry of the intended activities and focus areas? | No | Yes |

| Does the plan show where enforcement actions are likely to be taken? | No | Yes |

| What level of deterrence does the plan provide? | General | Targeted |

Queensland Audit Office from information provided by the Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy and the Department of Environment and Science.

The regulators and the divisions within them adopt very different approaches to planning their monitoring and compliance activities. Furthermore, they consider coal seam gas risks to varying degrees in their compliance planning. This limits the regulators’ ability to profile specific risks relating to coal seam gas activities—for example, the risk of air pollution caused by gas escaping from pipes or other equipment. Assessments of coal seam gas-specific risks could better inform planning and improve the link between identified risks, activities, and the intended outcomes.

The regulators and their various divisions coordinate some of their compliance planning. There is an opportunity for them to improve their effectiveness by:

- increasing coordination and formalising compliance planning

- developing better tools and processes for sharing information from their different systems.

Three divisions within DNRME are responsible for regulating the coal seam gas industry—the Resources, Safety and Health Division, the Georesources division and the Natural Resources division. The department’s compliance framework is principle-based. Each unit uses the principles (Figure 1C) to develop its own procedures and guidelines to support its regulatory activities.

The Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy, National Resources compliance framework 2019–22.

Planning compliance monitoring of tenures

Each unit within DNRME develops its compliance plans and actions using its own documentation or recording system, none of which are linked. The multiple work units bring specific expertise to regulating the industry, but this necessitates effective coordination and planning. Figure 1D shows the work units within the department responsible for regulating various coal seam gas activities. The work units’ compliance plans cover all petroleum and gas activities and do not separate coal seam gas activities. In addition, the plans do not specifically identify the areas of greatest risk and community concern as areas of focus—such as groundwater management.

| Work unit, Division | Phase* | Coal seam gas responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

|

Petroleum and Gas Inspectorate Unit, Resources, Safety and Health Division |

Exploring |

Responsible for compliance with safety provisions outlined in Chapter 9 of the Petroleum and Gas (Production and Safety) Act 2004 and the Petroleum and Gas (Safety) Regulation 2018:

|

|

Engagement and Compliance Unit, Georesources Division |

Releasing land |

Responsible for:

|

|

Petroleum and Gas, Georesources Division |

Exploring |

Responsible for:

|

|

North, Central and South regions, Natural Resources |

Exploring |

Responsible for monitoring, assessing and responding to compliance with natural resource legislation including the water, vegetation management and land Acts, as well as priority agricultural areas (PAAs) and strategic cropping areas (SCAs) under the Regional Planning Interests Act 2014. |

|

Strategy and Capability, Natural Resources |

Exploring |

Provides support to the regions to ensure compliance matters are dealt with in a consistent, timely and appropriate manner. This support includes development and management of business processes, policies and guidelines. |

Notes: *where the area is likely to be involved in the coal seam gas activity phases (see Figure A).

The Office of Groundwater Impact Assessment administratively sits within DNRME.

Queensland Audit Office from information provided by the Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy.

The various compliance plans cover information such as the number of inspections, audits, and/or engagements the unit is targeting for the period. However, most plans do not provide details about the:

- level of industry coverage

- risks the plans are targeting

- frequency of inspections

- outcomes the unit intends to achieve.

We observed some good practices. The Petroleum and Gas Inspectorate within DNRME has adopted a risk-based approach to regulate workplace health and safety for the coal seam gas industry. It uses its analysis of risks to inform its compliance plan and to identify specific areas of focus. For example, in 2019 it undertook a specific compliance assessment project focused on wells, including audits and inspections of wells for statutory compliance. It engaged with industry and stakeholders to educate them on its findings and promote better practices. DNRME’s Engagement and Compliance Unit last compiled an annual compliance plan in 2017–18. Its 2017–18 compliance plan provided high-level targets on the number of audits, inspections, and stakeholder engagements it intended to undertake.

The Georesources Division (of which the Engagement and Compliance Unit is a part) has developed a divisional compliance strategy across its work units and their respective regulatory functions. This is a positive move towards better coordinating the division’s compliance activities.

The Department of Environment and Science

Planning compliance monitoring of environmental authorities

DES compliance planning has elements of good practice as it is risk based, which allows DES to prioritise and target its resources. However, it is organised under the Environmental Protection Regulation and this limits its scope. For example, hydraulic stimulation/fracturing is not an environmentally relevant activity on its own under the Environmental Protection Regulation and, therefore, DES does not report on it separately. DES’s model could be enhanced by including industry specific risks and analysis. DES could also make its compliance plan public to inform industry and the public of its areas of focus and deter non-compliance.

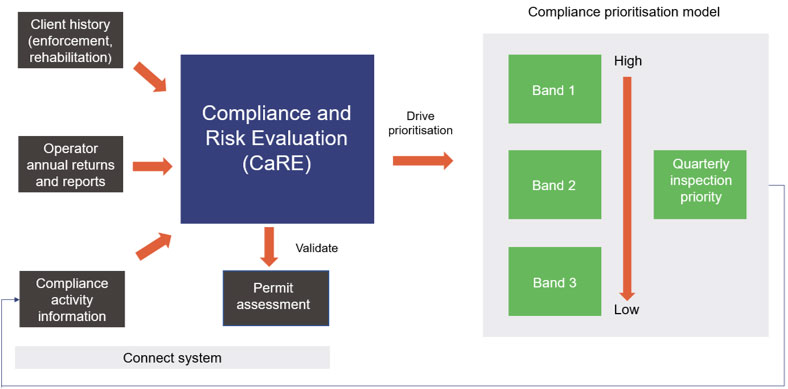

DES prioritises its inspection activities based on its assessment of the operator and site risk profile. It applies this model to all industries it regulates. Because the framework is client and site specific it does not consider industry specific risks or compliance levels across specific industries, such as the coal seam gas industry. Figure 1E details the DES compliance framework.

Queensland Audit Office, taken from Follow-up of Report 15: 2013–14 Environmental regulation of the resources and waste industries (Report 1: 2017–18).

DES has commissioned a review of this framework and is further refining it.

Regional compliance planning

The DES regions responsible for compliance monitoring and enforcement of coal seam gas activities are the South West Queensland and Central Queensland regions. These regions develop quarterly compliance plans and detail:

- objectives

- resources

- inspection workload and schedules

- business rules and requirements for inspecting band 1, 2 or 3 sites

- previous enforcement actions requiring follow-up activity.

The compliance plans are risk based through input from the compliance prioritisation model and knowledge of the regional compliance officers.

The regional compliance plans cover all industries the department regulates. They could be improved by specifying specific risks, priorities or activities for each industry group—such as ground water management and quality; air quality; and testing for fugitive emissions, management of coal seam gas water and salt waste.

DES compliance plans are not made public (for example, by publication on the DES website) or broadly communicated outside the department. They therefore have limited value in:

- informing the industry of the regulators’ intended activities and areas of focus

- promoting operators to proactively self-assess for non-compliance

- deterring non-compliance

- enhancing public confidence that the industry is well regulated.

Auditing and inspecting for compliance

Audit and inspections data

It is not possible to identify an accurate and reliable number of audits or inspections the regulators have undertaken of the coal seam gas industry. Our efforts to link the data from the various areas of the regulators proved problematic because:

- the regulators do not identify coal seam gas activities as distinct from other petroleum and gas activities in their databases

- units with regulatory responsibilities have different recording methods and systems and do not coordinate their activities

- no one takes responsibility for coordinating compliance information across the department.

Similarly, matching or linking the data between the two regulators is difficult and results in discrepancies in the number of authorities and leases related to coal seam gas.

From the data we obtained, neither we nor the regulators could be sure of identifying all authorities to prospect, petroleum leases, and environmental authorities for coal seam gas activities. Identifying coal seam gas activities from the data requires assumptions and data manipulation. Consequently, we and the regulators were unable to verify the complete authorities and leases for coal seam gas activities with any degree of confidence. DNRME advised us that it will transition to a new online application system within the next two years. They advise us that the system will allow them to specifically identify coal seam gas exploration and production applications.

The regulators have started work to improve their data capability. For example, DNRME started a project in October 2018 to move its existing data platform to a new platform that will provide it with greater business analytics capability. DES started a project in July 2019 to implement a compliance tracking system to improve information quality and reporting capability.

The Department of Environment and Science

Individual site inspections

The regional areas of DES conduct individual site inspections. Due to limitations in the current database, the regional areas record inspections and compliance information in a legacy database instead. DES is currently working towards migrating the information to a common platform to ensure data consistency and accuracy across its areas.

Proactive audits and inspections (planned)

DES inspection reports focus on activity outputs. For example, DES conducted 40 proactive coal seam gas inspections that covered companies A, B and C in the 2018–19 financial year. It does not identify how frequently DES was inspecting key industry risk activities and community concerns such as:

- storage, management and treatment of coal seam gas water

- re-injection of ground water

- management and disposal of salt and brine waste

- hydraulic fracturing

- air quality monitoring.

Although the specific information on inspections for these risk activities exists in individual audit and inspection reports, DES does not capture, collate and report on this information at an aggregate level. Because the information is not publicly available, the government and public have limited assurance that DES is adequately targeting its inspections to manage high-risk issues and that its actions in managing these risks achieve adequate outcomes.

Reactive audits and inspections (complaints and notifications)

Between January 2015 and June 2019, DES conducted 507 reactive audits and inspections. These include landholder and community complaints, and industry notifications of incidents or exceedances of conditions. Figure 1F shows that the number of complaints and notifications have decreased from 140 in 2015 to 70 in 2018. The regulators and commission attribute this to maturing of the industry and better landholder relations. While this is plausible, there is no objective evidence to verify that this is the reason for the decrease.

| Year | Number of complaints and notifications |

|---|---|

| 2015 | 140 |

| 2016 | 143 |

| 2017 | 119 |

| 2018 | 70 |

| To June 2019 | 35 |

Queensland Audit Office, from data obtained from the Department of Environment and Science.

The Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy

Individual site inspections

Each regulating unit of DNRME records information specific to the type of audit or inspection it conducts. DNRME provides staff with adequate guidelines, checklists, and templates for conducting inspections. The audit and inspection reports we viewed varied, but generally contained adequate detail of the inspections undertaken, findings, and actions taken. The reports could be improved by providing additional details, such as follow-up actions (future inspections), time frames, and compliance trends that may indicate broader issues of the industry.

Proactive and reactive audits and inspections

DNRME is unable to provide a collective number of proactive and reactive audits and inspections because each work unit plans and records its work using different methods and repositories. There is an opportunity to develop a collaborative approach to collect insights from these activities. The information can be used for future planning and provide a better understanding of where the main risks are.

Addressing stakeholders’ complaints

As part of their regulatory functions, DNRME and DES are responsible for enforcing different legislation. At present, DNRME does the triaging for most complaints. However, the regulators have different procedures for dealing with complaints, different reporting requirements and varied methods of data collection. This reduces their ability to share a collective understanding of the coal seam gas industry and be proactive in identifying risk areas. Therefore, they would benefit from establishing a collaborative data sharing platform to facilitate better exchange of information.

The regulators have adequate documentation to guide staff on managing complaints within their jurisdiction. They have set up memorandums of understanding and informal arrangements with other agencies to resolve complaints and to minimise duplication. However, some landholders we interviewed indicated that they were dissatisfied with the process because the regulators could not resolve some of the complaints due to legislative constraints.

Similarly, stakeholders with health and safety concerns or complaints can be frustrated by the number of regulators and the complex regulatory framework. The nature of the health and safety issue and where it occurs (whether onsite, in access areas, or as an offsite impact) will contribute to determining which regulator has jurisdiction—DNRME, Workplace Health and Safety Queensland, or DES. Some circumstances may require two or all of these regulators.

Enforcing compliance

For effective enforcement, the regulators should have a range of enforcement actions available to them to address various levels of non-compliance.

We found the regulators could demonstrate they have used an effective range of enforcement options to address non-compliance in coal seam gas activities. However, the information captured by the regulators does not facilitate easy extraction of coal seam gas industry examples. In addition, it does not capture enough information about the outcomes, for example, whether the operator rectifies the non-compliance issue.

Figure 1G shows the hierarchy of enforcement options used by DES for any non-compliance with environmental authority conditions for all industries it regulates. DNRME uses similar enforcement options.

The Department of Environment and Science

Figure 1H shows the type of enforcement actions that DES has used on environmental authorities between February 2016 and August 2019—ranging from issuing warning notices, statutory compliance notices, and infringement notices to prosecution.

In its service delivery statements, DES reports on the proportion of non-compliant licensed operators (environmental authority holders) it monitors that subsequently return to compliance. This is a measure of its effectiveness where it has taken corrective action to assist non‑compliant operators to meet their environmental obligations. It targets 70 per cent of these non-compliant operators being returned to compliance. DES has reported achieving its target each year since 2015–16 and exceeding it in 2016–17 (actual was 79 per cent).

While this is a good measure of effectiveness, its reported figure is aggregated for its actions across all operators it regulates. DES does not assess its performance on this measure for each industry and, therefore, does not monitor its performance for the petroleum and gas industry or more specifically the coal seam gas industry. We, therefore, cannot determine the effectiveness of the enforcement actions for the coal seam gas industry.

| Enforcement actions* |

Number of occasions** between February 2016 and August 2019 |

|---|---|

| Formal investigation request | 19 |

| Information notice | 2 |

| Notice to conduct or commission an environmental evaluation |

3 |

| Notice to show cause | 4 |

| Penalty Infringement Notice | 75 |

| Warning letter | 4 |

Note: *Sample actions.

** All environmental cases not just related to coal seam gas activities.

Queensland Audit Office, from data provided by the Department of Environment and Science.

The Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy

In significant cases, DNRME can suspend or cancel leases. Recently, DNRME cancelled the petroleum lease of a coal seam gas operator. This is its first cancellation. Case study 2 shows the details of that cancellation.

| Cancellation of lease due to non-compliance |

|---|

|

In 2019, DNRME cancelled a petroleum lease for a coal seam gas operator due to unpaid fees and lack of recorded resource production. This is the first time DNRME has cancelled the lease of a coal seam gas operator for non-compliance. DNRME granted the lease in 2010 to two companies (Company A and Company B), each with a 50 per cent interest in the lease. Company A held a 20 per cent share of Company B. Since 2014, the two companies accrued unpaid rent, interest and penalties. In July 2018, the minister gave Company A notice of a proposed non-compliance action. Following subsequent correspondence between DNRME and the companies and submissions made by the companies, DNRME concluded that the companies did not have the financial resources or ability to manage production. The minister’s delegate subsequently approved cancellation of the lease in September 2019. |

Queensland Audit Office from information obtained from the Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy.

Reporting on regulatory effectiveness

DES has a service standard that measures the effectiveness of the compliance program—the proportion of monitored licensed operators returned to compliance with their environmental obligations. This measure reports an aggregate number that includes all the industries DES regulates. DES does not internally or externally monitor and report on non-compliant operators returned to compliance at an industry level. Therefore, it does not track the number of coal seam gas companies that have moved back into compliance after non-compliance as a measure of the effectiveness of its compliance monitoring program for the coal seam gas industry.

Until late 2015, DES developed regular intelligence assessment reports for each of the main industries it regulates, including coal seam gas. These reports were detailed and provided valuable information for regulating the industry, and planning compliance monitoring and enforcement activities. They provided analysis and assessment of inspections, notifications, complaints, enforcement activities, issues, trends, environmental risks, client risks, location profiles, regulatory decisions, financial assurance, monitoring techniques, industry developments, and identified gaps. The department stopped producing these intelligence assessment reports in 2015. The department has no alternative reports that provide this detail nor any regular assessments of the coal seam gas industry and the effectiveness of its regulatory activities. Instead, if requested, ad hoc intelligence assessments are produced for specific issues.

In April 2019, DES produced a dashboard for its gas activities. This dashboard contained some useful information on its activities over the prior three-month period, including:

- industry information and statistics

- list of new environmental authority permit holders

- count of inspections conducted by type and client

- enforcement actions undertaken

- count of unplanned compliance events reported to it by type (complaint or notification) and client.

The dashboard is a useful tool for understanding activities, but in isolation it does not provide an indication of the effectiveness of DES’s regulatory activities. DES should develop regular detailed reports on the effectiveness of its activities, including outcomes.

DNRME has also separately started to use a dashboard to report on regulatory efficiency. However, the current database does not separate coal seam gas from other resource activities. This makes it difficult to report on efficiency of the coal seam gas regulatory functions.

Decommissioning

With the growth and maturing of the coal seam gas industry, assurance over the decommissioning of coal seam gas wells and infrastructure is now becoming a more frequent requirement for regulators.

DNRME’s Petroleum and Gas Inspectorate and DES’s Energy, Extraction and South West Queensland Compliance Unit regulate the decommissioning of coal seam gas wells. However, DES has not conducted any decommissioning activities because the environmental authority holders have yet to surrender their permits. The holders only surrender their environmental authority when they terminate all the work onsite, which may include multiple coal seam gas wells.

DNMRE has inspected 25 coal seam gas wells out of the 1,976 decommissioned wells (1.2 per cent), as of June 2019. Neither regulator has conducted onsite inspections to observe companies’ operations during the decommissioning process. As the number of wells being decommissioned increases, the regulators need to consider reviewing their approach to ensure they continue to regulate the process effectively. For example, they should consider the timing and frequency of inspections and the auditing of operators’ decommissioning processes. Once the wells have been plugged by the operator, there is nothing to inspect. For this reason, it is important to gain assurance over an operator’s process for decommissioning.

At the time tenure and environmental authorities are surrendered, coal seam gas operators, in most cases, decommission and rehabilitate disturbed land or features during their operations, for example, dams, water treatment plants and roads. However, in some cases, operators may retain the asset. Leaving beneficial assets can be advantageous to the operator and the landholder as the operator does not have to pay to rehabilitate the feature and it enables the landholder to use it after surrender. There is an opportunity for regulators to strengthen the current process to allow for the transfer of beneficial assets from operators to landholders, but there are issues around the transfer of risk (referred to as residual risk). DES is currently working with industry to provide clarity around implementation of the existing residual risk framework to ensure a consistent and transparent process.

2. Engaging and managing stakeholders

This chapter covers how effectively the regulators and the GasFields Commission Queensland are engaging, supporting and managing stakeholders to promote coexistence and ensure a viable coal seam gas industry.

Introduction

Most coal seam gas activity in Queensland occurs in the state's agricultural regions. The coal seam gas and agriculture industries are both important to the state's economy. Agriculture is vital for the nation's food security and gas contributes to meeting the nation's energy needs.

As the coal seam gas industry grew in Queensland, so did landholder and community tension with industry and the government. Some of this concern was about the effectiveness of government departments in regulating this growing industry.

In recognition of this, the government set a policy of promoting coexistence. Coexistence with landholders and regional communities is crucial to the onshore gas industry maintaining its ongoing acceptance by the general public.

The regulators—the Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy (DNRME) and the Department of Environment and Science (DES)—have a key role in engaging with stakeholders and promoting coexistence. They do this by engaging, educating and advising industry, landholders, communities and government.

In addition, the Queensland Government established the GasFields Commission Queensland (the commission) as part of the Department of State Development, Manufacturing, Infrastructure and Planning in 2012. The commission became an independent statutory body in July 2013 under the Gasfields Commission Act 2013 (the GFC Act).

The GFC Act sets the purpose of the commission as being to:

… manage and improve the sustainable coexistence of landholders, regional communities and the onshore gas industry in Queensland.

To achieve this, the GFC Act identified 14 functions of the commission, which are detailed in Appendix E and can be categorised into three broad interrelated categories:

- Facilitation—facilitating better relationships between (and education and information to) landholders, regional communities and the onshore gas industry

- Oversight—reviewing the effectiveness of government entities in implementing regulatory frameworks related to the onshore gas industry

- Advisory—providing advice and making recommendations to ministers and government entities and, in some cases, to industry about identified areas, assessment applications, and leading practice.