Overview

The risk of new invasive plants or animals arriving on our shores is a constant threat to Queensland. Once here, they can be destructive, spread serious diseases, kill our native species, cause agricultural loss, and affect our lifestyle – and are costly and difficult to eradicate or manage. Scientists estimate that invasive plants and animals cost the Australian economy between $5–7 billion annually. In Queensland, state and local governments, land managers, relevant industries, and the community all share responsibility for managing invasive species.

Tabled 4 July 2023.

Report on a page

Invasive plants and animals (invasive species) affect the lives of all Queenslanders and are estimated to cost the Australian economy between $5 and $7 billion each year. Biosecurity Queensland is a business group of the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries. It leads Queensland’s response to prevent and recover from pests and diseases threatening our agriculture, the environment, social amenity, and human health. It works with state and local government entities to manage invasive species. We found that although these entities are doing a lot to manage invasive species, Biosecurity Queensland needs to take greater leadership in its oversight and coordination role to reduce the impact of some species.

Reducing the impact of invasive species

Stronger leadership and effective strategy are needed to address key challenges

The Department of Agriculture and Fisheries’ role, through Biosecurity Queensland, is to lead the biosecurity system. However, it has not clearly articulated how it will deliver on its crucial leadership role.

The Queensland invasive plants and animals strategy 2019–2024 does not address some of the key challenges facing the biosecurity system, like increasing biosecurity risk and the limited capacity of some entities. It aspires to reduce the impact of all invasive species, without clearly defining which ones are a priority for entities with a role in managing invasive species.

Gaps in assessing and prioritising risk

There is significant variation in how state entities and local councils assess the risk of invasive species and prioritise their activities. Some have mature systems and processes and others do not have any. Despite its role as system leader, Biosecurity Queensland does not have a documented framework for assessing and prioritising the risk of invasive species. It does prioritise its effort, but it is difficult to determine whether its focus is always on the right species.

Responding to established invasive species

Biosecurity Queensland is taking a proactive approach to keep new invasive species out of Queensland and detect quickly those that do arrive. This aligns to the state strategy and is consistent with what industry experts recognise as the most cost-effective way to reduce their impact. However, it is not actively coordinating a state-wide approach across entities to manage established invasive species. For example, neither it nor the Department of Environment and Science have a state-wide plan to manage feral cats, despite their significant impact on our native wildlife. Biosecurity Queensland could better assist councils to more effectively use the powers of the Biosecurity Act 2013 to regulate biosecurity risk.

Eradicating fire ants

Biosecurity Queensland is leading a national effort to eradicate fire ants from Queensland. Despite significant effort and funding, fire ants have now spread to over 700,000 hectares across South East Queensland. Initial delays in gaining funding approval across Commonwealth and state governments, and in commencing treatment, likely contributed to the spread. Expert views on whether eradication is still feasible vary, but the benefits of eradicating fire ants are apparent. Continuing to try to eradicate fire ants will take considerably more commitment and funding from the Commonwealth and state governments beyond what has already been provided. The significant commitment and funding necessitate that Biosecurity Queensland provides greater transparency about its progress as it seeks to mobilise governments and councils, the community, industries, and local businesses to do more in the fight against fire ants.

We made 8 recommendations to improve how entities assess, prioritise, and mitigate the risk of invasive species, design their strategies, use data to inform their decisions, and report their progress.

1. Audit conclusions

The risk of new species of invasive plants and animals arriving on our shores is a constant threat. Once here, they are destructive, costly, and difficult to eradicate or manage. Many state entities and local governments are doing a lot to manage invasive species and reduce their impact across our state. However, greater leadership, oversight, and coordination is needed to ensure they are more effective.

The Department of Agriculture and Fisheries has not clearly determined how it will effectively deliver on its biosecurity system leadership role. As a result, its leadership is not as strategic or as effective as it could be.

The Queensland invasive plants and animals strategy 2019–2024 (the strategy) does not address some of the key challenges facing Queensland’s biosecurity system. While it aspires to reduce the impact of all invasive species it does not recognise that some entities, particularly remote councils, have little capacity to do so. State and local government entities need to be realistic about what they can achieve, and this heightens the need for effective leadership, planning, risk assessment, prioritisation, and coordination.

These gaps in leadership and strategy inhibit Biosecurity Queensland’s ability to identify and coordinate preventive and response priorities. It is unclear which invasive species are a priority (with some exceptions, such as fire ants), who decides the priorities, or how this is determined. Furthermore, Biosecurity Queensland does not have a complete view of its funding for all invasive species programs. Therefore, it cannot ensure its funding is effectively prioritised to achieve the best overall outcomes and provide value for money.

Detecting invasive species early and keeping them out of Queensland is the most effective way to reduce their impact. This has been a focus of Biosecurity Queensland and it has had some notable success. For some invasive species, Biosecurity Queensland is proactively using technology to detect and, where possible, eradicate them. However, Biosecurity Queensland also needs to take ownership for responding to established species (because they are widespread) in Queensland, including setting priorities and coordinating activities. In many cases, management of established species is largely left to local councils without adequate support or coordination. For example, there is no state-wide plan to manage feral cats, despite them destroying native wildlife and significantly contributing to the extinction of some ground‑dwelling native birds and small- to medium-sized mammals.

Between 2001 and 2022, Commonwealth and state governments, under the National Red Imported Fire Ant Eradication Program, spent $644 million to eradicate fire ants in Queensland. The infestation and spread of these ants are recognised as a significant state and national economic, health, and social threat. Efforts to initially eradicate and later manage these ants in China and the United States have been largely unsuccessful and resulted in significant cost and impacts. Biosecurity Queensland has worked hard to slow the spread and eradicate fire ants. To date, the eradication efforts have had isolated and limited success. Its efforts to slow the spread of the ants in Queensland has contributed to the rate of spread being significantly less than experienced in China and the USA, but still the infestation has continued to grow. Inadequate containment boundaries, as well as uncertainty and delays in funding, slowed treatment to control the spread and eradicate these ants.

Biosecurity Queensland has continued to learn and adapt its approach and is refocusing its strategy to manage and eradicate fire ants. It estimates an additional $593 million (which includes Commonwealth and state governments funding) will be needed over 4 years from 2023–27 to implement its new strategy. Expert views vary on whether eradication can be achieved, but the economic, health, and social cost of not trying is high. If its new strategy is to be successful, at a minimum, Biosecurity Queensland must ensure that it establishes adequate containment boundaries, and it must effectively mobilise and coordinate the community, industries, local businesses, and councils to take a greater role in treating fire ants. Importantly, it must be more transparent about the rationale of its decisions and its progress, including performance metrics focused on outcomes, rather than outputs. If left to spread, fire ants could cost Queensland and the country billions of dollars. Decisions about what to do next should be guided by independent assessments grounded by scientific data and modelling.

2. Recommendations

|

Strengthening biosecurity system leadership and coordination |

|

We recommend the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries:

|

|

Designing an effective strategy |

|

We recommend the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries:

|

|

Using data to inform decision making |

|

We recommend that the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries:

|

|

Assessing and mitigating the risk of invasive species |

|

We recommend the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries:

|

|

Regulating the risk of invasive species |

|

We recommend the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries:

|

|

Responding to fire ants |

|

We recommend the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries:

|

Reference to comments

In accordance with s. 64 of the Auditor-General Act 2009, we provided a copy of this report to the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, the Department of Environment and Science, and to all local councils. In reaching our conclusions, we considered their views and represented them to the extent we deemed relevant and warranted. Any formal responses from these entities are at Appendix A.

3. Invasive species in Queensland

Invasive plants and animals can have devastating impacts on our economy, our environment, and our health. They spread serious diseases, kill our native plants and animals, cause agricultural loss, and affect our lifestyle. Scientists estimate that invasive plants and animals cost the Australian economy between $5 and $7 billion each year.

What makes something invasive?

Invasive species are generally any introduced plant or animal species that has an adverse economic, environmental, human health, or social impact. Invasive species may be introduced intentionally (such as the cane toad) or unintentionally (such as the red imported fire ant). However, even a native species can be included in the definition of invasive species. For example, native locust swarms can be considered invasive because they devastate crops and cause major agricultural damage. Once established, invasive species can be extremely difficult and costly to eradicate or manage.

The Biosecurity Act 2014 (the Act) defines an invasive plant or animal as a species that has or is likely to have an adverse impact on a biosecurity consideration because of the introduction, spread, or increase in population size of the species in an area.

Who is responsible for managing invasive species?

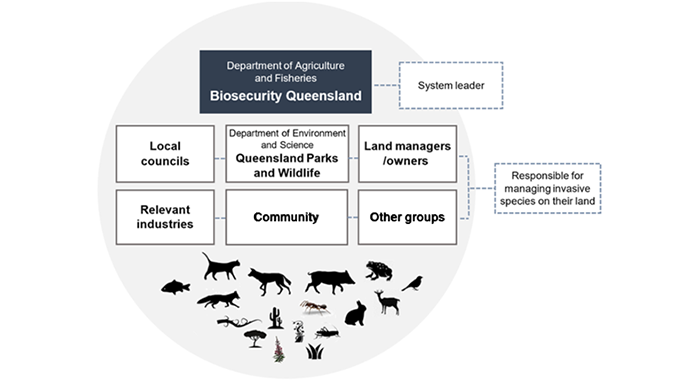

Queensland’s biosecurity system relies on many stakeholders working together effectively to eradicate or reduce the impact of invasive plants and animals. Figure 3A shows the key stakeholders in the system.

Notes: Other groups include natural resource management groups, community, and environmental groups.

Queensland Audit Office.

Under the Act, every person has a general biosecurity obligation to prevent or minimise biosecurity risk (such as invasive plants and animals) on their land.

Biosecurity Queensland is a business group in the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, and is responsible for leading the biosecurity system and mitigating the risk of invasive plants and animals across the state.

Other public sector entities have a role in managing invasive species on land they are responsible for. For example, Queensland Parks and Wildlife (within the Department of Environment and Science) is responsible for managing invasive species in parks and forests across the state. The Department of Environment and Science is also responsible for protecting species that are at risk of extinction (threatened species). Councils are responsible for having a biosecurity plan and managing invasive species in their local government area.

Entities must effectively plan and coordinate their activities at a national, state, regional, and local level, to reduce the impact of invasive species. This is specifically important as borders and geographical boundaries have no relevance for species.

What did we audit?

In this audit, we assessed how effectively state and local government entities are managing invasive plants and animals. We did not examine how effectively entities manage biosecurity incidents for major disease outbreaks, such as foot and mouth disease.

4. Reducing the impact of invasive species

In Queensland, state and local governments, land managers, relevant industries, and the community all share responsibility for managing invasive species. Everyone has a responsibility. Land holders, whether they be government, industry, or the community, must act to prevent, eradicate, and control invasive species. The biosecurity system requires effective leadership and coordination, especially because invasive species spread across borders and geographical boundaries. This means that local narrowly focused initiatives are rarely likely to have long-term success in isolation.

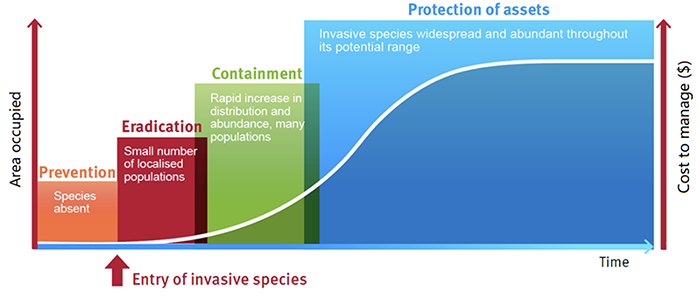

Entities must regularly assess the risk of invasive species to determine which species are a priority and the most effective way to manage them. They must act quickly and collectively. Once an invasive species becomes established and widespread, like the cane toad, it becomes difficult or even impossible to eradicate. For this reason, prevention or early eradication is the most effective way to reduce their impact.

This chapter is about whether entities have effective leadership and strategy to reduce the impact of invasive species on our economy, environment, and our lifestyle. We also look at how entities prioritise their effort and how effectively they plan and coordinate their activities.

Does Queensland have effective leadership and strategy to reduce the impact of invasive species?

Leadership for the biosecurity system needs to be strengthened

Biosecurity Queensland’s 2022–23 plan states that its purpose is to:

lead and promote a biosecurity system that protects Queensland’s economy, environment, lifestyle, and human health.

However, neither the strategy, nor the Biosecurity Act 2014 (the Act), state that Biosecurity Queensland has a leadership role. Given Biosecurity Queensland’s role is to lead the system, it is important that both the strategy and the Act clearly define this, so stakeholders across the system understand its leadership role.

Biosecurity Queensland has established several committees to help lead Queensland’s biosecurity system. These committees provide a valuable forum to share information and collaborate about approaches to preventing, eradicating, and containing invasive species. But the committees do not lead and direct effort across the system. Several stakeholders said there was a lack of leadership and coordination across the system.

The need for strong leadership and coordination is even more essential given entities within the biosecurity system have different responsibilities, priorities, capacity, and capability. For example, Biosecurity Queensland’s primary focus is invasive species that have an economic impact, whereas the Department of Environment and Science focuses on those species that have the greatest environmental impact. Similarly, local councils have varying priorities based on their geographic location, the spread and impact of invasive species in their area, and the needs of their community.

While these varying responsibilities and priorities are at times complementary, they can also be competing. Especially considering the increasing risk of invasive species and the finite resources and funding to manage them. This means effective leadership, alignment of strategies, and coordinated planning is essential to avoid duplication and maximise outcomes. Biosecurity Queensland fulfilling this statewide leadership and coordination role should in no way diminish the biosecurity responsibilities and accountabilities of councils, landowners, and individuals.

|

Recommendation 1 We recommend the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries strengthens its leadership and coordination role for the biosecurity system by setting strategic priorities, prioritising funding, and coordinating and overseeing activities across Queensland. Recommendation 2 We recommend the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries reviews the Biosecurity Act 2014 in consultation with stakeholders, to ensure it has the necessary clarity, authority, and responsibility to effectively and efficiently lead, coordinate, and enforce Queensland’s biosecurity system. |

Strategy does not address key challenges

Queensland’s biosecurity system faces significant challenges. Biosecurity risk is increasing, and entities are under pressure to do more with the resources they have. These are not new challenges. The Queensland Biosecurity Capability Review (September 2015) highlighted these problems.

Biosecurity Queensland, in collaboration with other stakeholders, developed and implemented the Queensland invasive plants and animals strategy 2019–2024 (the strategy). The strategy includes key principles, such as the importance of strategic, risk-based planning. It also outlines the benefits of preventing and eradicating invasive species before they become established.

However, the strategy fails to identify, and does not address, some of the key challenges facing the biosecurity system, such as the capacity and capability of councils to manage invasive species. It does not include an approach to overcoming these challenges. It aims to reduce the impact of all invasive species, without clearly defining what entities should focus on. Councils and state entities need to carefully decide where to put their effort, given the resource constraints that many face.

Need to align strategies

The Queensland invasive plants and animals strategy 2019–2024 acknowledges the environmental impacts of invasive species. However, it does not refer to, or align with, the Department of Environment and Science’s Biodiversity Conservation Strategy, which was published after the Queensland invasive plants and animals strategy. The strategy does not identify which invasive plants and animals pose the most risk to threatened species.

Invasive species can have a significant impact on native species, including threatened species. In some coastal areas of Queensland, researchers estimate that feral pigs destroy approximately 90 per cent of turtle nests each year. This includes the nests of the endangered Loggerhead, Olive Ridley, Hawksbill, and Leatherback turtles. To reduce the impact of invasive plants and animals on native species, entities responsible for managing invasive species need to align their strategies and coordinate their activities.

Biosecurity Queensland and the Department of Environment and Science need to work together, and better align their existing and new strategies if they are to protect our native wildlife from invasive species.

|

Recommendation 3 We recommend the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries reviews, updates, and implements the Queensland invasive plants and animals strategy 2019–2024. The strategy should:

|

Need to measure and report progress

Performance across Queensland’s biosecurity system

It is unclear whether entities are winning the fight against the invasive species that they are managing. They do not monitor and report on the outcomes of their activities across the biosecurity system. For example, entities do not regularly report how many invasive species they have successfully eradicated, how many they are trying to eradicate, and how many they have failed to eradicate. Nor do they report how much funding they spend on invasive species or the economic benefits.

The Queensland Invasive Plants and Animals Committee (QIPAC) is responsible for reporting annually on progress against the strategy. Since the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries established QIPAC in November 2018, it has finalised one report. The 2-page document provides some useful insights, but it does not report against the progress of the strategy. Nor does it state whether Queensland is reducing the impact of invasive species. QIPAC is drafting its next progress report.

Performance of individual programs

Some entities monitor the progress and outcomes of programs for individual invasive species and produce detailed reports. Biosecurity Queensland produces detailed reports about the performance of some of its individual programs. These reports highlight the work underway and the outcomes of that work. They can increase awareness about risk for other entities and inform their planning. Figure 4A is an example of the detailed reporting that Biosecurity Queensland performs for bitou bush.

| Eradicating bitou bush from Queensland | |

|

Bitou bush (Chrysanthemoides monilifera) is native to South Africa. It is an aggressive weed that spreads quickly, replacing native plants and destroying the habitat of native animals. New South Wales’ Department of Planning and Environment estimates that it has spread to 46 per cent of the NSW coastline. In contrast, only isolated plants are being detected along Queensland’s coastline. Biosecurity Queensland has sought to eradicate bitou bush since it was first detected in 1981. Although it has not yet eradicated the weed, the number of detections has decreased significantly. Since 2011–12, the number of bitou bush detected in Queensland has decreased from 158 to 46 in 2020–21. Biosecurity Queensland reports annually on the outcomes of its bitou bush eradication project. Its 2020–21 annual report shows the number of areas it has inspected, and the number of weeds detected and treated. It includes maps of its treatment and surveillance activities and highlights the areas where it has eradicated bitou bush, such as Bribie Island. This information increases awareness about the risk and helps entities target their efforts. |

Bitou bush (Chrysanthemoides monilifera). Photo supplied by the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries. |

Queensland Audit Office using information provided by the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries.

Measuring outputs and outcomes

Entities can improve their performance monitoring by ensuring they have specific performance indicators that are relevant, achievable, and measurable.

Some of the entities we audited use performance metrics that focus on outputs, rather than outcomes. For example, Biosecurity Queensland reports the number of biosecurity incidents responded to, rather than the outcome of the response. Similarly, the Department of Environment and Science measures the percentage of pest programs delivered but does not state how many programs should be delivered or the benefits or improvements they are achieving. These indicators are unlikely to help these entities measure the effectiveness of their activities and drive the improvements they are seeking.

Many councils also lack performance indicators to measure and improve their performance. We surveyed all councils and, of the 61 that responded, 27 (44 per cent) reported their biosecurity plans did not contain key performance indicators. This is a gap they need to address if they are to effectively measure their performance.

Using data to monitor and report performance

Biosecurity Queensland does not have a complete picture of the number or spread of invasive species that state and local government entities are trying to manage across the state. It is not accurately and consistently recording all invasive species it is managing in its Biosecurity Online Resources and Information System (BORIS) – which is the database it uses to record and manage invasive species information. Neither is it recording all activities it is undertaking to manage invasive species in BORIS.

Accurate and complete data can provide entities with rich insights. Equally, poor data can limit entities from understanding what they are doing well and what they can improve. Biosecurity Queensland cannot confidently measure and report its performance due to inaccurate and incomplete data in BORIS. Biosecurity Queensland’s staff record information in BORIS inconsistently. Some record all surveillance activities; others only record those surveillance activities where they detect an invasive species.

Some Biosecurity Queensland staff reported that they could not easily track their surveillance activities, due to limitations with BORIS. They also manually upload the surveillance data that other agencies share.

|

Recommendation 4 We recommend the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries improves the accuracy and level of detail it records about invasive species, their risk, and the activities it does to manage them. This should include:

|

Our previous report and recommendations on performance measures, roles and responsibilities, and reporting on outcomes

Six years ago, in Biosecurity Queensland's management of agricultural pests and diseases (Report 12: 2016–17), we recommended that the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries:

- continues to develop an appropriate number of specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and timed key performance indicators for each of Biosecurity Queensland’s key activities or initiatives. In doing so, it should plan how to collect and analyse data to monitor these key performance indicators; collaborate with industry and other stakeholders on the collection of data; and evaluate the success of key activities or initiatives in delivering the desired outcomes

- improves quarterly reporting processes by not only reporting on inputs and activities for key biosecurity initiatives, but also on risks and progress towards achieving objectives and outcomes to support strategic management decisions

- when it participates in pest and disease management strategies which share responsibilities with other entities, clearly determines its roles and responsibilities; the key performance indicators that will be used to assess its contribution to the strategy; and which entity is best placed to monitor performance of the strategy and evaluate it at appropriate intervals.

Our report 2021 status of Auditor-General’s recommendations (Report 4: 2021–22) captured the department’s self-assessed progress in implementing these recommendations. The department reported that each recommendation had been fully implemented.

During this audit, however, we found these 3 recommendations from our previous report had been only partially implemented. While the department is developing key performance measures, we found an absence of specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-based indicators across biosecurity activities. Also, while the strategy includes roles and responsibilities, there is a lack of coordination and regular monitoring of performance against objectives and outcomes.

Where entities report fully implementing our recommendations, we expect their actions to address the issue that we identified and to be operating effectively. There should not be a plan to address the issue or be inconsistently implemented across relevant activities.

Which invasive species get priority?

The lack of leadership across the system has resulted in a lack of clarity regarding the priorities for the state. Except for fire ants, it is unclear which invasive species in Queensland are a priority, or how this is determined and by whom.

Gaps in assessing and prioritising risk

Assessing risk regularly

Assessing risk regularly helps determine which invasive species are a priority. It is one of the objectives of the strategy.

Biosecurity Queensland does not have a documented framework, procedures, or guidelines for assessing the risk of invasive species. Nevertheless, it has performed detailed risk assessments for some species. In 2016 it assessed and published the risk of 83 invasive species, including their existing and potential spread, and impact. It has only updated one of the 83 risk assessments since 2016. Further to this, it has not published risk assessments for wild dogs and feral pigs, which are 2 species that have a significant impact on the economy and the environment. Failing to regularly assess the risk of invasive species inhibits Biosecurity Queensland’s and its stakeholders’ ability to make fully informed decisions and prioritise species programs and management.

Prioritising invasive species

Biosecurity Queensland’s policy on invasive plants and animals states that its priorities are high-risk species not established in Queensland or those that are established but can still be eradicated. The policy identifies 75 species as high risk, but it does not explain why it considers them high risk or rank them by priority. We found other entities, including some local councils, also did not clearly identify which invasive species were a priority. Entities are more likely to maximise their impact by clearly defining priorities.

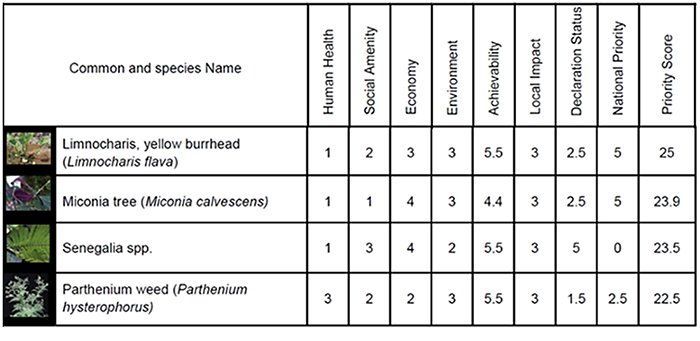

There were, however, exceptions. Cairns Regional Council uses a documented framework to assess, prioritise, and plan its activities. It assesses the impact of each invasive species, highlights whether the species is a state or national priority, and outlines whether it can eradicate them. It ranks each species and prioritises those with the highest score. This provides a sound platform to ensure its decisions are consistent and transparent. Biosecurity Queensland and other councils could benefit from using this framework or a comparable framework. Figure 4B shows an excerpt from Cairns Regional Council’s risk matrix tool.

Note: Priority scores for impacts use a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being the lowest impact and 5 the highest impact; Achievability uses a scale of 1.1 to 5.5; Local impact uses a scale of 3 to 5; Declaration status uses a scale of 1 to 2.5; and National priority uses a scale of 2.5 to 5.

Cairns Regional Council’s Biosecurity Plan 2019–2024.

Prioritising resources based on risk

Knowing which invasive species to focus on, and where to invest limited Commonwealth and state funding, is vital. Much of the funding spent by councils on invasive species comes from grant funding.

Biosecurity Queensland does not know how much money state and local governments are spending on managing invasive species. Neither it, nor any other state entity, captures this information. As a result, it is impossible for the Queensland Government to know its total spending on invasive species.

In 2020–21, Biosecurity Queensland spent $27 million on managing invasive species. This included $17.4 million on operations and program management, $6.1 million on research, and $3.6 million on policy and engagement. Biosecurity Queensland did not capture the funding it spent on individual invasive species, except that which it allocated under the Queensland Feral Pest Initiative.

We examined the grant funding allocated to individual invasive species under this initiative, which has been in place since 2016. Between 2016 and 2021, Biosecurity Queensland allocated over $40 million in grant funding under this initiative. The Commonwealth contributed $14 million and Biosecurity Queensland $26 million.

Figure 4C shows where Biosecurity Queensland allocated grant funding between 2016 and 2021.

Note: Funding for capacity building included establishing working groups and education and awareness activities.

Queensland Audit Office using data supplied by Biosecurity Queensland.

Since 2016, Biosecurity Queensland allocated more than 70 per cent of the grant funding to cluster fencing (fencing used to control wild dogs, which have a significant impact on agricultural production and native wildlife). Cluster fencing can also help manage other invasive species, such as feral pigs.

We found a lack of objective rationale for how Biosecurity Queensland allocated funding across the various species based on their impact, such as feral cats. We present a case study on feral cats later in this report.

Sharing information about biosecurity risk

Entities need to get better at sharing information about biosecurity risk. This is particularly important if the risk of a species changes, a program or its funding is ceasing, or an entity decides to change how it manages a species. For example, Cairns Regional Council said it was given little warning when Biosecurity Queensland decided to change its approach to siam weed, from eradication to containment, and the funding for the program was going to cease. When this occurred, the council did not have the capability to manage the weed. Other councils raised similar challenges in relation to other invasive species.

Biosecurity Queensland’s interactive dashboard maps the risk of invasive plants across the state. Councils and other stakeholders can see the current and historical spread of invasive plants and better understand their risk and prioritise effort. Entities can maximise the value of this information by collectively assessing and analysing it and using it to prioritise their effort. Expanding this mapping tool to include invasive animals would benefit stakeholders.

|

Recommendation 5 We recommend the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries develops and implements a framework for assessing and mitigating the risk of new and established invasive species. The framework should include:

|

What are entities doing to prevent and eradicate new invasive species?

Greater focus on preventing and eradicating invasive species

Keeping invasive species out of Queensland and detecting them early is the most effective way to reduce their impact. Biosecurity Queensland is taking a proactive approach to prevent and, where possible, eradicate new invasive species (those not established in Queensland). This aligns to the state strategy and is consistent with what industry experts recognise as the most cost-effective way to manage invasive species.

Figure 4D shows the key stages of managing invasive species and highlights the economic benefits of preventing and eradicating invasive species.

Queensland invasive plants and animals strategy 2019–2024 with slight modification by QAO.

As part of its planning in 2021, Biosecurity Queensland identified several invasive species that it could prevent or quickly eradicate, including Asian black-spined toads and red-eared slider turtles. Both species have the potential to have a significant economic, environmental, and social impact.

Biosecurity Queensland’s south region is actively using an application to automatically search platforms, like eBay, to identify the sale of invasive plants and animals, which can significantly impact the environment and agriculture. Between July 2017 and July 2022, it seized over 2,900 invasive cacti, such as prickly pear, by monitoring the internet and other surveillance techniques.

How are entities responding to established invasive species?

Responding to established invasive species

Biosecurity Queensland provides limited leadership for managing established invasive species in Queensland. Thus, some species are having a greater impact on our environment and the economy than they need to.

Biosecurity Queensland staff are unclear about its role. A common view among staff we spoke with was that it is only responsible for new invasive species and that councils are responsible for established species. This view is not consistent with Biosecurity Queensland’s 2022–23 plan.

Under the Act, councils are responsible for managing established invasive species on their land. However, Biosecurity Queensland, as system leader, also has a critical role to play in relation to established species, such as:

- setting strategic priorities

- prioritising funding

- assessing their risk

- undertaking research

- helping coordinate and oversee activities.

State and local government entities must carefully consider each established species and decide collectively what, if any, action they should take.

For some established species, like the feral cat, there is no statewide approach and entities do not effectively coordinate their activities. Thirty-four per cent (21) of the 61 councils that responded to our survey reported low to very low levels of coordination and collaboration with the state government in managing invasive species.

Managing feral cats

Feral cats pose a significant impact on biodiversity, particularly regarding native species. Scientists estimate there are between 2.1 and 6.3 million feral cats in Australia. The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation estimates that feral cats kill 1.8 billion Australian animals (reptiles, frogs, birds, and mammals) every year, many of which are listed as vulnerable or threatened species. Further detail on the impact on threatened species can be found in our report Protecting our threatened animals and plants (Report 9: 2022–23).

Despite this, the Queensland Government has no strategy to manage feral cats across the state. To varying degrees, entities do what they can to manage their risks, but do not coordinate and prioritise their efforts. This limits their ability to reduce the impact of invasive species on our native wildlife.

Some entities, like the Department of Environment and Science, are taking a more proactive approach to managing feral cats. Figure 4E is a case study about the work it is doing in 2 national parks to manage the risk of feral cats.

| Managing feral cats | |

|

Feral cat (Felis catus) in outback Queensland, Australia. Adobe Stock. |

The Department of Environment and Science identified the native wildlife in national parks across the state that are vulnerable to feral cats. It assessed the risk to these species and developed programs to protect them from feral cats. For example, it identified that the greater bilby population in the Astrebla Downs National Park in Western Queensland was at risk. Since 2012, the department has killed approximately 3,000 feral cats. The population of greater bilbies seen in the park has increased from 4 in 2014 to 225 in 2020. Similarly, it identified that feral cats threatened the endangered bridled nail‑tailed wallaby. Taunton National Park has the only known wild population of the bridled nail-tailed wallaby. The department commenced a baiting and shooting program to reduce the number of feral cats in the park. Since 2007, the number of endangered wallabies has increased from approximately 70 to 1,265 animals in 2020. It is critical that councils neighbouring these national parks also take a proactive approach to managing the risk of feral cats, otherwise their efforts are likely to be less effective than they could be. |

Queensland Audit Office using information provided by the Department of Environment and Science.

Most councils have a biosecurity plan

Councils must have a biosecurity plan under the Act, and most do. Ninety per cent (69) of the 77 councils in Queensland have a published plan. The other 10 per cent (8) do not have a plan and are not meeting their responsibilities under the Act. Three of these councils have a draft plan and are in the process of finalising them. The lack of planning by some councils limits how effectively they can manage invasive species in their area.

We reviewed councils’ plans and found they varied significantly in quality and completeness. Some councils do not document the invasive species in their area. Others do not assess the risk of species and prioritise their activities accordingly. For example, the red imported fire ant is a significant risk in South East Queensland. Four councils in South East Queensland do not list fire ants in their biosecurity plans. We discuss Queensland’s response to fire ants in Chapter 5 of this report. Similarly, yellow crazy ants are a highly aggressive invasive ant. Townsville City Council identifies them as a critical priority in its biosecurity plan and is currently managing several infestations. However, other neighbouring councils do not list them as a risk in their plans.

We found that more than 23 per cent (16) of the 69 published plans have not been updated since 2017. This diminishes their value. A biosecurity plan needs to be a living document. Councils need to alter their approach as risks and priorities change and update their plan accordingly.

Biosecurity Queensland, in collaboration with the Local Government Association of Queensland, developed guidance material to help councils develop their biosecurity plans. It maintains a register of councils that have a plan, but it does not review and approve plans or provide feedback. It also does not try to ensure consistency and coordinate across council plans where appropriate. There is no strong impetus for councils to regularly review and update their plans.

Do entities issue biosecurity orders?

Entities are reluctant to issue biosecurity orders

As we have found in many past audits, good regulatory performance is about enforcing minimum prescribed standards – yet, in many cases, regulators are not enforcing these standards. We share insights about good regulatory practices in our better practice guide: Insights for regulators.

There are a range of tools that state and local government entities can use to regulate the risk of invasive species, including biosecurity orders. While in many cases education and information will be sufficient, there will nevertheless be circumstances where issuing orders will be needed.

Under the Act, Biosecurity Queensland and councils have the power to issue biosecurity orders where a person fails to meet their general biosecurity obligation. For example, they may issue an order that compels a person to remove an invasive plant from their property.

Biosecurity Queensland has issued 13 biosecurity orders for invasive species (excluding the 54 orders issued for fire ants between 2017–21) since the Act came into effect in 2014. Two of its 5 regions, central and south regions, have issued no biosecurity orders. We heard from several biosecurity officers that it was not their role to issue orders, even though they have the requisite powers.

Most councils are also reluctant to issue biosecurity orders. For example, one of the largest councils in South East Queensland has not issued any orders and another has only issued 2. Some councils preferred to educate landholders, rather than issue biosecurity orders.

In contrast, some councils, like Bundaberg Regional Council, are proactively regulating biosecurity risk in their area. It uses a range of compliance options, including issuing warning letters to individuals failing to meet their general biosecurity obligation. It recommends what the individual needs to do and, for those that fail to act, it issues a biosecurity order. Bundaberg Regional Council has issued more than 1,500 biosecurity orders since the Act was enacted.

|

Recommendation 6 We recommend the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries provides greater education and awareness to local councils about how they can use the powers of the Biosecurity Act 2014 to regulate the risk of invasive species. This should include:

|

5. Eradicating fire ants

Fire ants are one of the worst invasive species in the world. They originated from South America and have spread to many countries, including the United States, China, Taiwan, and Japan. Fire ants are highly aggressive, inflicting painful bites on people, pets, and livestock. The United States estimates that fire ants alone cost its economy about $5–7 billion a year.

Fire ants can have devastating impacts on Queensland’s agriculture and tourism industries, and severely impact our lifestyle. Biosecurity Queensland is leading a national effort to eradicate fire ants from South East Queensland.

This chapter details our audit findings and conclusions about Queensland’s response to fire ants. We look at how Queensland is responding to fire ants, its progress in eradicating them, and its planned future action.

How is Queensland responding to fire ants?

|

Fire ant (Solenopsis invicta). iStock image. |

Fire ants were first detected in South East Queensland in 2001. Figure 5A shows a timeline of events since fire ants were first detected. |

Fire ants first detected at the Port of Brisbane and at Richlands, in the western suburbs of Brisbane.

Fire ant detections decreased, and the infestation appeared to have been almost eradicated. As a result, state and Commonwealth entities reduced funding.

Scientific review found the infestation had increased and they needed better treatment methods to contain the infestation.

Biosecurity Queensland mapped the spread of fire ants across South East Queensland using helicopters fitted with cameras.

*National Steering Committee approved a 10-year eradication plan and the Commonwealth and states committed $411 million in funding.

Biosecurity Queensland commenced broadscale eradication and containment activities.

10-year eradication program is scheduled to finish.

Note: *The National Steering Committee was established in July 2017 to provide guidance and support to the program’s operational team on all aspects of the program’s delivery to ensure that it has the best chance of achieving its objectives.

Queensland Audit Office using information provided by Biosecurity Queensland.

National Red Imported Fire Ant Eradication Program

The National Red Imported Fire Ant Eradication Program commenced in 2017. The program focuses on finding, containing, and eradicating fire ants from South East Queensland. Biosecurity Queensland is leading and coordinating this national program. It reports to a national steering committee that provides strategic oversight, leadership, and guidance. We did not audit the committee.

The Australian Government and all Australian states and territories share the cost of the program. The Commonwealth provides approximately 50 per cent of the funding, and states and territories the remaining 50 per cent. Since 2001, Biosecurity Queensland has spent $644 million trying to eradicate fire ants from South East Queensland. It expects that it will exhaust all funding by June 2023.

The program is supported by a 10-year eradication plan. The plan outlines the priority areas and the key phases. The first 2 phases involve searching for and treating fire ants. The final phase involves searching treated sites and confirming if the area is free of fire ants.

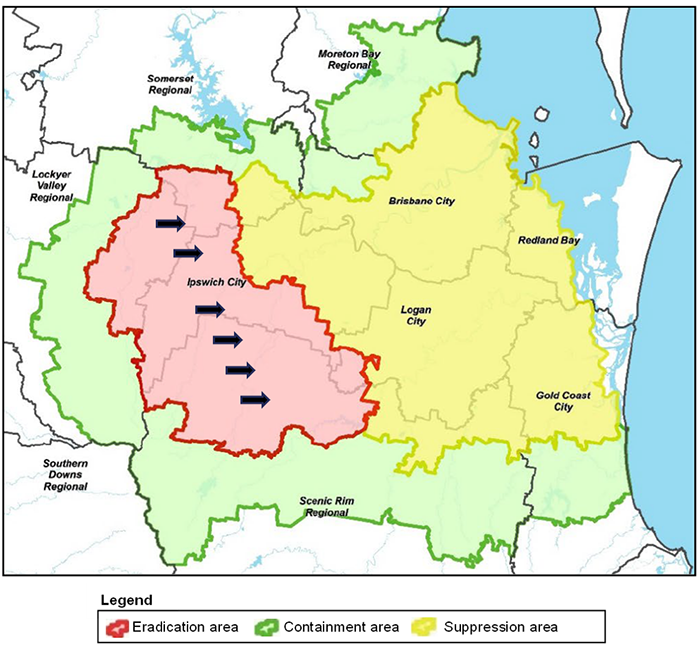

Biosecurity Queensland has been working from west to east, prioritising eradication efforts in suburbs in Ipswich, Lockyer Valley, Scenic Rim, and Somerset. These areas presented the greatest risk because of their habitat, and the potential for fire ants to spread quickly and have a significant impact. At the same time, Biosecurity Queensland has sought to suppress fire ants in the eastern suburbs of Brisbane and contain them from moving further north or south.

Figure 5B shows the fire ant eradication, containment, and suppression areas for 2022–23.

Note: The eradication, containment, and suppression areas have changed over time as new fire ants have been detected.

The National Fire Ant Eradication Program website with slight modification by Queensland Audit Office.

Can Queensland eradicate fire ants?

Eradicating any invasive species can be challenging, particularly invasive ant species like fire ants. Entities need to continue assessing their progress and decide if it remains both feasible and economical to do so. This is a requirement under Australia’s National Environmental Biosecurity Response Agreement, which took effect in November 2021. To be eligible for Commonwealth funding, an eradication program must satisfy these requirements. The fire ant program commenced before this agreement took effect. Nevertheless, Biosecurity Queensland needs to be able to answer these questions.

At present, expert views vary on whether it is still feasible to eradicate fire ants from Queensland. Despite significant effort and funding, they have continued to spread across South East Queensland. In January 2023 fire ants were found on North Stradbroke Island, and in June 2023 were discovered near Toowoomba – both outside the containment area.

Biosecurity Queensland appears to have slowed the spread of fire ants – since 2001, they have spread approximately 3–5 kilometres per year. This rate of spread is much lower than what has occurred in other countries. International research indicates that fire ants have spread approximately 48 kilometres per year in the United States and 80 kilometres per year in China. Nevertheless, they have still spread.

Fire ants are difficult to eradicate. A single colony can have thousands of fire ants and multiple queens. Biosecurity Queensland eradicated 5 separate infestations: at Yarwun, Port of Gladstone, Brisbane Airport, and 2 at the Port of Brisbane. The largest of these was 8,300 hectares at the Port of Brisbane. The remaining infestation, first detected in 2001 at Richlands in South East Queensland, has now grown to more than 700,000 hectares.

Fire ant detections are increasing

Biosecurity Queensland detects fire ants through its surveillance activities. It uses helicopters, sniffer dogs, on-ground inspections, and electronic monitoring of sites near the boundary of the containment area. It also receives reports of fire ants from the public. Since 2007, the number of sites where fire ants have been detected has increased significantly from 116 to 12,388 in 2022.

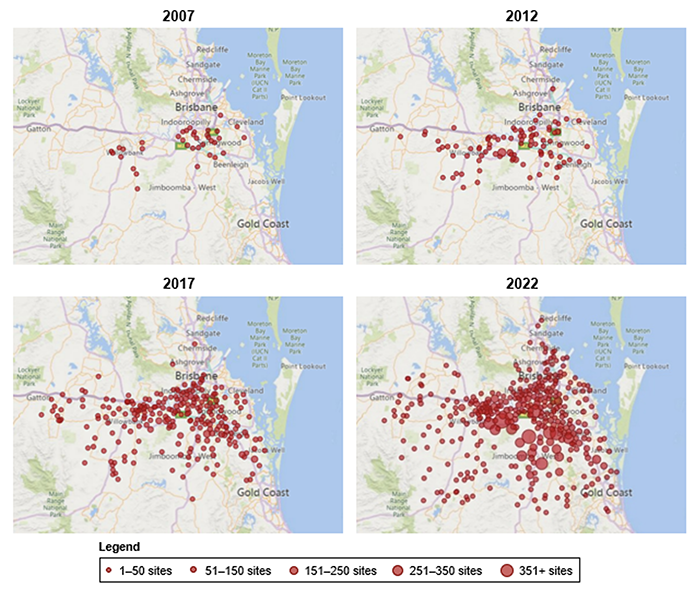

Figure 5C shows the number of sites where fire ants have been detected in South East Queensland in 2007, 2012, 2017, and 2022. The size of the bubbles represents the number of sites at that suburb.

Queensland Audit Office using data provided by Biosecurity Queensland.

The increasing number of fire ant detections cannot solely be attributed to the spread of fire ants. Greater community awareness and education is likely to have contributed to the number of detections. Improved technology, including more sophisticated cameras, may have also contributed. It can be difficult to quantify the extent to which these factors have increased the number of detections. Biosecurity Queensland does not do this analysis.

Appendix B shows, by suburb, where 50 or more sites of fire ants have been detected between 2007 and 2022.

Detections in the eradication area

Biosecurity Queensland has prioritised treating fire ants in the eradication area west and southwest of Ipswich. Measuring the number of detections in this area is an important indicator of the program’s performance. We analysed fire ant detections in 20 suburbs that were in the eradication area since July 2017. Between 2017 and 2019, the number of detections decreased substantially. However, this number has almost doubled each year since 2019. In 2022, the number of detections were similar to those observed when the 10-year program commenced.

Figure 5D shows the number of sites with fire ants in the 20 suburbs within the eradication area from 2017 to 2022.

Queensland Audit Office using data provided by Biosecurity Queensland.

Feasibility of eradicating fire ants

The National Steering Committee has commissioned regular reviews and evaluations of the program. Some of these have assessed whether it is technically feasible to eradicate fire ants from South East Queensland. Independent reviews in 2015 and 2016 concluded that it was still technically feasible and economical to do so.

In 2019–20, the National Steering Committee engaged a university to determine the geographic boundary (size and location) of the fire ant infestation. The university concluded that it could no longer determine the boundary. This is an important aspect of determining whether it was still feasible to eradicate fire ants.

In August 2021, the National Steering Committee commissioned a strategic review to examine the program’s effectiveness and whether it was still feasible to eradicate fire ants from South East Queensland. It concluded that it was unclear whether it was technically feasible to eradicate fire ants. On page 47, the National Red Imported Fire Ant Eradication Program Strategic Review August 2021 report states:

Based on previous successes, the containment of polygyne infestations and the elimination of RIFA [red imported fire ants] from significant portions of SEQ [South East Queensland], it is still considered biologically feasible to eradicate the ants. However, due to the scale of the infestation at this point, and outstanding uncertainty regarding the effectiveness and strategic use of RSS [remote sensing surveillance] in routine operations, the technical feasibility of eradication is unclear at this time.

In view of Program outcomes to date and current risks of spread, a major change of strategy is needed for any possibility of long term eradication and even for continued mitigation of a build-up of infestation with consequent serious problems. Gains made to date must be preserved if possible, while a new strategy is put in place. In the longer term, eradication may eventually be feasible, but only with major changes in program scope, strategy, budget and governance, and possibly with new technologies.

We spoke with national and international subject matter experts about the feasibility of eradicating fire ants in South East Queensland given the size of the infestation. Some of these experts contrasted the size of the current infestation (approximately 700,000 hectares) to the size of the largest infestation ever successfully eradicated globally (8,300 hectares at the Port of Brisbane) and expressed uncertainty about the feasibility of eradicating fire ants in South East Queensland.

Cost benefits of eradicating fire ants

An eradication program must provide benefits larger than costs. In September 2021, Biosecurity Queensland engaged a university to assess if it was still economical to eradicate fire ants from South East Queensland. It was not engaged to assess if it was still feasible to eradicate fire ants. It analysed the cost benefits of the eradication program based on it costing $300 million each year for 10 years and fire ants spreading 5km per year in scenario 1 and 48km per year in scenario 2. For scenario 1 it estimated a negative net loss of $303 million over 15 years. For scenario 2 it estimated the net benefit would be at least $430 million over 15 years. Both scenarios demonstrate positive net benefits by year 16. This analysis assumes but does not scientifically conclude that it is feasible to eradicate the fire ants. It does not consider the risk of the program failing to eradicate fire ants.

Helping other jurisdictions eradicate fire ants

Biosecurity Queensland continues to help other jurisdictions eradicate invasive ants. To date, it has helped eradicate small, isolated fire ant infestations from New South Wales, Victoria, Northern Territory, South Australia, and Western Australia. It sent its biosecurity officers and detection dogs to help eradicate these infestations.

More transparency is needed about outcomes

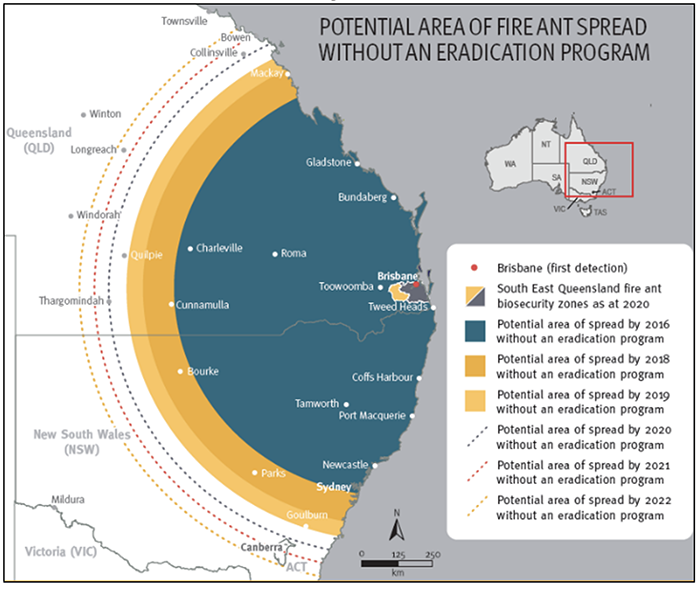

It is difficult to determine how Queensland is progressing with eradicating fire ants from South East Queensland based on publicly available information. Biosecurity Queensland has many performance metrics and reports regularly and publicly on its activities. However, it does not clearly highlight the outcomes of the program. For example, in its annual performance report 2020–21, it reported the potential spread of fire ants without an eradication program, but not the actual spread. Figure 5E shows this.

National Fire Ant Eradication Program Annual Performance Report 2020–21.

It calculated the spread in Queensland based on the rate that occurred in the United States (48 kilometres per year). It mapped the linear spread of fire ants from the Port of Brisbane from 2001. It is unlikely that fire ants would spread at the same rate in all directions. It is more likely that they would spread along the main transport corridors, and in areas where the habitat is most suitable. This includes the main highways north, south, and west of Brisbane where fire ants can spread through the transport of earth and plant materials, like soil and mulch, as well as through the movement of machinery.

Biosecurity Queensland has developed many key performance indicators to measure performance. Some of these are valuable. For example, it measures and reports the number of significant detections outside the containment area. This is an important metric, because Biosecurity Queensland must act quickly to identify and treat fire ants outside the containment area. It may also need to expand the containment area if there are high numbers of significant detections. It could enhance this measure by including how quickly it treats significant detections. However, many of its metrics focus on outputs, not outcomes. For example, it reports the number of hectares that it surveys and treats for fire ants, but not the outcome of that work. In addition to this, a lack of consistent metrics has made it difficult to compare performance year on year.

Biosecurity Queensland needs to report its progress more transparently, including the challenges it is facing. The community, industries, local businesses, and councils need to better understand:

- the current size of the infestation

- the impact of fire ants and the risk of them spreading further

- what they can do to manage them.

They need clear and consistent messaging. This is particularly important given Biosecurity Queensland is seeking to mobilise the community, industries, and other entities to treat fire ants more actively on their land.

What is Queensland planning to do next?

The strategic review performed in August 2021 concluded that the current program could not eradicate or contain fire ants within the scope and budget of the 10-year plan. It highlighted delays in planning and commencing broadscale treatment had allowed fire ants to spread. It presented 3 options:

- Contain, suppress, and eradicate fire ants by 2032

- Contain and suppress fire ants

- Wind down the program and transition to each state managing fire ants.

In November 2021, the National Steering Committee met and discussed the proposed options. In January 2022, it recommended to the agriculture ministers to continue with eradication, including:

- undertaking more surveillance outside the containment area to ensure fire ants do not move beyond the boundary

- greater focus on suppressing fire ants that have become increasingly entrenched in urban areas east of the current eradication area. This includes mobilising councils, communities, and all land managers to take a more active role suppressing fire ants on their land

- stronger compliance of industries that create habitat that is attractive to fire ants.

Biosecurity Queensland reported the cost of continuing with eradication is estimated to be approximately $593 million over 4 years from 2023–27. A decision about approving the additional funding is yet to be made.

|

Recommendation 7 We recommend the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries strengthens its approach for assessing the progress and outcomes of the National Fire Ant Eradication Program. Decisions about what to do next should be guided by independent assessments grounded by scientific data and modelling. This should include periodically assessing whether it is technically feasible to eradicate fire ants from Queensland. Recommendation 8 We recommend the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries reports its progress in eradicating fire ants from Queensland and the outcomes of its activities. This should include developing and reporting regularly on performance measures that show how well the program is achieving its outcomes, such as the size of the fire ant infestation over time. |