Overview

Demand on Queensland's health system is increasing as the population ages and grows, health technology advances, and communities develop higher expectations about what services they can access. Likewise, increased financial pressure and the COVID-19 pandemic have placed additional strain on the system to meet demand within available resources. To provide sustainable healthcare, Queensland Health must plan well.

Tabled 25 March 2021.

Auditor-General’s foreword

The 2020 year has brought healthcare to the fore in the minds of governments and communities as they grappled with the effects of the COVID‑19 pandemic. People in Queensland have relied on the fact that safe and effective health services will be available to them where and when they need it.

While the current public focus may be on dealing with COVID-19, the Department of Health and the hospital and health services (HHSs)—collectively known as Queensland Health—have continued to support the ongoing health needs of people in Queensland. I paused this audit between April and September 2020 to allow Queensland Health to focus on the initial public health response. Since that time, Queensland Health has commenced work to address many of the issues and recommendations I have raised in this report.

Healthcare does not operate in a vacuum. Factors such as income levels, education, social supports, and individual lifestyle choices and behaviours influence the health of individuals. Apart from seeking to influence lifestyle choices, addressing these factors is largely outside the responsibility of Queensland Health, but they can make a difference to the level of healthcare that Queensland Health needs to provide.

Queensland Health is one part of the health system, working with others such as the recently formed Health and Wellbeing Queensland, general practitioners, private hospitals, and aged care providers. In some instances, HHSs have partnerships with other providers within their region, but this can be enhanced. I will explore how well Queensland Health works with these providers in future audits on healthcare pathways and managing integrated care of chronic disease.

Long-term planning with other Queensland government agencies is another area that Queensland Health and other agencies can improve. I intend to undertake an audit of how Queensland Health and the Department of Education work together on their strategies to prevent childhood obesity.

Apart from the state government, the Australian Government and local governments also play key roles in addressing the health needs of the community. This audit has also demonstrated the need for government agencies and different tiers of government to work more closely together to integrate their plans to achieve common aims and goals—whether this is improving direct healthcare, community amenities or educational opportunities.

Brendan Worrall

Auditor-General

Report on a page

We audited how effectively the Department of Health (the department) and the hospital and health services (HHSs)—collectively known as Queensland Health—work together to plan for a sustainable health system. We performed detailed work at the department and four HHSs.

We concluded that Queensland Health needs to take further action to ensure effective planning for sustainable health services. It has started to address many of the issues we raise in this report, with some HHSs more advanced than others. The Minister for Health and Ambulance Services' response to this report (at Appendix A) outlines some of Queensland Health's recently started and planned initiatives.

Working together

The separate parts of Queensland Health can work better on long-term plans and short-term initiatives. The HHSs have been established as independent entities, but they are dependent upon the department for most of their funding and staff. They can achieve more if they work across boundaries when planning how to best meet Queenslanders’ needs.

Effective planning is hampered by the lack of a consistent understanding of what a sustainable health system is and how the statewide and local level priorities complement each other. In October 2019, Queensland Health published its Queensland Health System Outlook to 2026 for a sustainable health service, which provides a framework to build this understanding.

Queensland Health generally consults well with its clinicians and communities when planning, but there is a lack of a consistent approach on how, with whom, and when it takes place.

Planning for the long term

In 2016, Queensland Health designed My health, Queensland’s future: Advancing health 2026 as a 10-year strategy to guide the Queensland Government’s long‑term investment in health. It does not have a clear implementation roadmap of how its health service plans and enabling plans (for example, workforce plans) contribute to achieving the objectives in this strategy.

Workforce plans are not in place for all critical roles. For example, Queensland Health does not have a statewide nursing workforce plan but is in the process of preparing one. HHSs have only recently started to strategically plan for their future workforce needs.

The department has not developed statewide plans for all services that have a large number of patients. Without these plans, there is a risk that planning by HHSs will be fragmented.

Queensland Health has a growing and ageing asset base. It has identified that it will need significant further investment to renew these assets and acquire new ones. However, it needs to improve its approach to decide the relative priority of future investments. The department now requires HHSs to improve their asset management data and reporting.

Monitoring success

While Queensland Health monitors its short-term initiatives against clear performance measures, it is not systematically collecting information on the impact of its long-term plans. Nor is it monitoring whether its strategies are contributing to the development of a more sustainable health system.

We made seven recommendations to Queensland Health to improve integrated planning, the capacity and capability of staff, priority setting, and evaluating a plan’s success.

1. About this audit

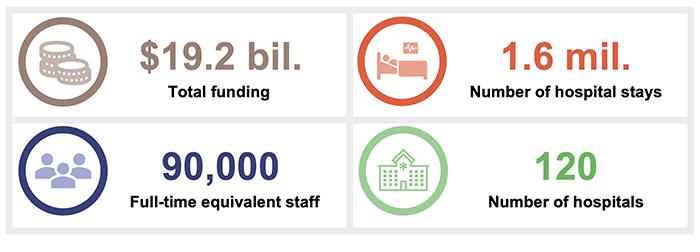

Healthcare demand is increasing as the population ages and grows, health technology advances, and communities develop higher expectations about what health services they can access. Hospital and health services are also experiencing increased financial pressures. This places pressure on providers to meet demand within available resources. To achieve this, they must plan well. Figure 1A provides some key facts about Queensland Health (the Department of Health and the hospital and health services).

Assembled by Queensland Audit Office from Queensland Health financial statements and patient data collection, and the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

The health system is currently under additional strain due to COVID-19 (which also delayed this report). However, it still needs to plan for a sustainable health system.

A health system is sustainable when it is sufficiently adaptable to changes in cultural, social and economic conditions and demands, and able to efficiently use limited resources (financial—funding, infrastructure—physical and technological, people—workforce, and environmental—energy/waste) to effectively meet the current and future health needs of the population.

2. Recommendations

We provided individual findings from our audit directly with each of the four in-scope hospital and health services, focusing in detail on the issues relevant to them. We have not reproduced those individual findings here; rather, we have focused on findings that are applicable across the system.

Department of Health

We recommend that the Department of Health:

1. implements a comprehensive integrated planning framework in collaboration with hospital and health services (Chapters 3 and 4)

This framework should:

- explain and demonstrate the interrelationships between health service plans, enabling plans (for example workforce, infrastructure, and funding plans), and other plans (such as strategic and operational plans)

- provide a common understanding of what a sustainable health system is

- provide guidance on collaboration within Queensland Health and on best-practice consultation approaches with clinicians, consumers, and other stakeholders

- provide guidance on best-practice implementation planning and design of appropriate evaluation techniques

- provide guidance on appropriate reporting arrangements and governance structures to monitor and report progress against plans.

2. develops a rolling, medium-term implementation roadmap to provide direction on how the outcomes in My health, Queensland’s future: Advancing health 2026 will be achieved (Chapter 4)

This roadmap should:

- clearly articulate the priorities at a system-wide level for a sustainable health system

- allocate actions to agencies, with clear time frames

- regularly evaluate success against clear performance indicators

- learn from previous plans and respond to changes in the external environment.

This should be undertaken in conjunction with implementing recommendation 14 of the Queensland Health governance review, which is about developing integrated plans for health services, workforce, and capital works.

3. prepares, implements, and evaluates statewide workforce plans for all critical employee groups (Chapter 4)

4. works with hospital and health services to strengthen the capability and capacity of the staff who support the planning process across the state (Chapter 4).

Hospital and health services

We recommend that all hospital and health services:

5. develop a set of priorities with clearer alignment to the statewide priorities (Chapter 3)

6. expand the scope of implementing recommendation 14 of the Queensland Health governance review by developing integrated plans at their level, also incorporating environmental action plans that align with the proposed framework in our recommendation 1 and statewide plans (Chapter 4)

7. develop appropriate performance indicators for health service and enabling plans, regularly evaluate the success of long‑term plans, and use learnings in future plans (Chapter 4).

|

Recommendation 14 of the Queensland Health governance review That in its role as system manager, the Department of Health should develop a comprehensive integrated statewide plan incorporating health service, workforce and capital works planning, and identifying future service challenges and demand pressures, demand reduction and management strategies, and future models of care. |

Reference to comments

In accordance with s. 64 of the Auditor-General Act 2009, we provided a copy of this report to relevant agencies. In reaching our conclusions, we considered their views and represented them to the extent we deemed relevant and warranted. Any formal responses from the agencies are at Appendix A.

3. Working together for a sustainable health system

This chapter covers how effectively the Department of Health (the department) and hospital and health services (HHSs)—collectively referred to as Queensland Health—work together to determine priorities and share innovation in the interests of providing a sustainable health system.

We examined whether the department and HHSs:

- have a shared understanding of what a sustainable health system is

- are clear about the priorities of the health system

- collaborate on planning initiatives and share quality data

- engage with clinicians, consumers, the community, and other organisations to inform their plans

- share learnings from the short-term initiatives they are pursuing.

Not everyone has a shared understanding of a ‘sustainable health system’

Queensland Health does not have a clear definition of a sustainable health system. This makes it hard for it to know whether it has a sustainable system or whether its plans will help achieve one.

Queensland Health references ‘sustainability’ in various documents when referring to healthcare, finances, workforce, assets, quality, and environmental factors. However, the term is not defined in any of the documents. This means that staff can interpret sustainability differently depending on their background and current role.

Different areas have different priorities

The department and HHSs we visited have their own frameworks for determining health system priorities and future investment decisions. Some HHS frameworks contain guiding principles to align with the department’s and government’s priorities, while others have a detailed prioritisation process. This makes it difficult for Queensland Health to undertake coordinated planning that aligns with its overall strategies.

Determining the priorities of the health system is an essential part of planning due to finite funding and human resources. Clear priorities also assist Queensland Health in balancing competing interests and communicating to its stakeholders why certain decisions are made.

The department and two of the HHSs we visited had no detailed prioritisation process for evaluating service proposals. These entities’ decisions generally considered alignment with their strategic plans, how their decisions addressed their current risks, and their available resources. They had more detailed prioritisation processes for infrastructure proposals. Since our fieldwork, the department has started to improve their prioritisation process.

In the two HHSs with a more detailed process, they considered a range of factors including service need, resourcing and safety with a consistent set of benchmarks for each factor. This helps these HHSs make more consistent decisions when assessing different proposals.

In 2019, the department commissioned a governance review, which recommended that the Minister for Health and Minister for Ambulance Services issue a statement of expectations to each board chair setting out government and ministerial expectations and priorities. The government and the department have not yet announced whether they have accepted this recommendation. Implementing the recommendation will assist HHSs to determine how their priorities benefit the entire health system. Queensland Health entities will need to evaluate proposals based on factors mapped to the statement of expectations.

More collaboration could make a difference

The department and HHSs consult reasonably well within their own entities when planning but could improve their consultation with each other.

People in the community want a system in which the various elements work together, and unnecessary duplication is reduced. This is important for HHSs that share boundaries, or when patients are referred to larger HHSs (for example, patients in regional areas being referred to HHSs in Brisbane). A change in the services in one HHS can affect another.

|

When a HHS cannot provide a service locally, the service may be provided by another HHS via telehealth. Telehealth allows patients to access health services using video conferencing. |

HHSs we met with identified telehealth as an area where collaboration could improve. A rural HHS that receives telehealth services from a regional or metropolitan HHS does not have input on the services to be provided and the times they are available. This resulted in one HHS engaging an interstate provider to deliver its telehealth services.

The department is in the final stages of preparing a longer-term telehealth strategy. This will help foster collaboration between stakeholders.

One recent initiative to improve collaboration is ‘Better Health North Queensland’, which is explored in Case study 1 (Figure 3A).

| Better Health North Queensland |

|

Better Health North Queensland (Better Health NQ) is a regional partnership established in 2017 between five hospital and health services, the Department of Health and two primary health networks (PHNs) in North Queensland. The purpose of Better Health NQ is for its partners to develop networks and work together to deliver cooperative health services that will improve healthcare for people in North Queensland. The partners established Better Health NQ due to:

These trends and the HHSs’ and PHNs’ individual strategies showed that the Better Health NQ partners had common priorities. These common priorities presented an opportunity to combine knowledge, technology, and services to reduce duplication and costs. While service providers still have local priorities they deliver individually, the Better Health NQ partnership allows for a combined, whole-of-region approach on their common priorities. While it is too early to assess the success of the partnership, a benefit of this whole-of-region approach is that it allows for a more integrated planning process that can be more effective in delivering services for people across North Queensland. |

Note: The Australian Government established PHNs to commission primary healthcare services, improve the efficiency and effectiveness of primary care, and improve the coordination of care.

Queensland Audit Office analysis of the Northern Queensland Health Service Master Plan (August 2019) and discussions with Mackay HHS and the Northern Queensland PHN.

Consulting with internal service providers earlier

The department provides the HHSs with diagnostic, scientific, and clinical support, as well as information technology services through two business units.

The business units need to be involved early in the department’s and HHSs’ planning processes to help them determine what support services to provide. This does not always happen, which shortens the time the business units have to plan their support services, and reduces their ability to positively influence their stakeholders’ plans.

Workforce capacity and capability to plan is varied

Workforce capacity and capability for health service planning varies across HHSs. The bigger HHSs have large planning teams with dedicated data analysts, while many regional and rural HHSs have one person who is responsible for planning as well as other responsibilities.

We heard examples of planning roles in some HHSs being vacant for several months while a suitable person was found. A HHS will find it difficult to plan effectively if the healthcare planner has a large workload with multiple responsibilities, or the planning team has vacancies for long periods of time.

|

Smaller HHSs can benefit from tapping into the expertise of larger ones. |

It is helpful for smaller HHSs to use the expertise of other planners in the system. A forum for executive directors of health service planning has recently been established, with the aim of bringing HHS planners together to share skills and information, improve capability, and strengthen relationships. It is co-chaired by representatives from one metropolitan and one regional HHS.

Smaller HHSs also rely on the department or larger HHSs to assist them with data analysis. For example, Metro North HHS has recently signed a memorandum of understanding with one of the rural HHSs to help it with data analytics and health service planning.

Quality data is shared, but not often enough

Health service planning relies on data about healthcare demand, workforce projections, and infrastructure. The department shares data and estimates on healthcare demand annually with HHSs. It also shares workforce estimates. HHSs share infrastructure data with the department for its strategic asset management plan. There can be a tension between having data that is reliable (historical) and data that is relevant (current).

Understanding healthcare demand in the community is a barrier

The lack of complete, quality data and estimates for Queensland Health services delivered outside of a hospital setting is a major barrier to accurately analysing service demand.

While HHSs have individual systems to capture demand for some of these services, there is no statewide data collection system. This limits their ability to proactively adjust plans to meet changing demand. The department is creating a planning guideline for projecting the demand for services it delivers outside of a hospital setting (such as wellbeing programs and chronic disease management), and it is making progress with collecting some of the data.

Accessing and validating data takes time

The department and HHSs have only recently launched a central source of datasets in a portal they can use to inform their service plans. It brings together useful information in a consistent format for health planners. However, it is still being populated and there are many other data elements that planners use that are not yet in scope or implemented.

HHSs use a combination of the department’s datasets and their own datasets, and spend time validating that data. This is a challenge for those HHSs without specialist skills in data analytics, particularly in regional and rural areas.

The intention is for the portal to assist regional and rural HHSs to easily access the common datasets they need in a user-friendly format. It is also intended to ensure greater consistency of data use across Queensland Health.

Future considerations for operating as a network

The governance review included recommendations on the health system’s obligations to strengthen linkages, include opportunities for discussion of strategic issues, and have a collaborative planning process. Our audit supports the findings that the department and HHSs need stronger collaboration.

The competition between HHSs for the finite amount of resources will present a challenge for true collaboration. When the department makes decisions for the good of the statewide system, it will need to clearly communicate its reasons—particularly if the decision impacts on individual HHSs. It will also be important for all entities involved in the collaborative planning process to consider enabling areas such as workforce, funding, and infrastructure.

More engagement could make a difference

There is value to planners and service providers in developing an engagement strategy at the start of a planning process. It makes it easier to know who to engage with, and when and how.

The Hospital and Health Boards Act 2011 (the Act) requires HHSs to have a clinician engagement strategy and a separate consumer and community engagement strategy, both of which they must review every three years.

Clinician involvement in developing plans is generally strong

The HHS clinician engagement strategies we audited met the requirements of the Act broadly.

Queensland Health generally engages well with clinicians when preparing health service plans and workforce plans, and includes their feedback in the plans. Consultation on other plans (for example, infrastructure) is less frequent or happens later in the planning process, reducing its effectiveness.

Some HHSs have consultation strategies for plans that outline who to consult with and when. These HHSs have followed their engagement plans.

Consumer and community views are usually heard

The consumer and community engagement strategies of the HHSs we audited met the requirements of the Act broadly, though some strategies did not address all required areas.

Consultation with consumers and community members varies across HHSs. Some HHSs involve consumers when developing particular health service plans. Others have community advisory groups that are integral to the planning process and directly affect the outcome.

|

Involving consumers and community members improves the quality of plans. |

One community advisory group described how it has regular meetings with the HHS to stay informed on planning activities. It provides input and raises concerns with the HHS, and this process helps it to give feedback to members of the community. Strong two-way communication has helped this HHS better meet the community’s needs.

The governance review recommended Queensland Health develop a good practice guide for hospital and health service boards that champions meaningful consumer and community engagement. While this recommendation is aimed at boards, our findings about consumer and community engagement are also relevant at management and policy development levels in the HHSs (and in the department). It is important that the benefits be shared across all of Queensland Health.

Working with other government and non-government entities

Partnering with primary health networks is working

Each of our in-scope HHSs has agreed a collaboration protocol with its local primary health network (PHN) and has engaged with it when developing health service plans.

HHSs and PHNs share de-identified data to inform the planning process, but there are challenges with what data is available and how it can be shared. Most data systems have been primarily built around billing rather than data collection. Different privacy legislation across jurisdictions can also complicate who can share and access data.

Some HHSs have joint plans with their PHN to capture all the health services their communities receive. Others have formed partnership arrangements, one of which is described in the following case study (Figure 3B).

| North Brisbane and Moreton Bay Health Care Alliance |

|

In 2017, Metro North HHS and the Brisbane North PHN entered an agreement to form the North Brisbane and Moreton Bay Health Care Alliance (the Alliance). The Alliance identified three population groups it believed needed a different healthcare service approach because their health needs were often driven by their social needs (poverty, drug or alcohol addiction, and social isolation). The Alliance saw an opportunity to combine knowledge, networks, and resources to deliver more efficient healthcare services that considered the social needs of these three groups. The Alliance’s collaboration has benefited from PHN connections to the community and non‑government agencies, and Metro North HHS’s access to short-term care information. |

Queensland Audit Office analysis of the North Brisbane and Moreton Bay Health Care Alliance agreement and discussions with Metro North HHS and Brisbane North PHN.

The department is finalising a process for HHSs to work with PHNs to produce a local area needs assessment.

Other healthcare providers are often not involved in planning

HHSs regularly work with other healthcare providers (private hospitals, non-government organisations, and other community groups) to deliver services to the community. However, we saw limited examples of other healthcare providers being engaged when HHSs are planning for services.

In some cases, entities are unwilling to share information due to commercial-in-confidence and patient confidentiality concerns. Also, when a HHS provides the majority of services in a region (particularly in rural and remote areas) it may not engage with other healthcare providers, as they have limited ability to affect how the HHS delivers its services. This is particularly the case with smaller non-government providers.

Case study 3 (Figure 3C) shows how a HHS improved its collaboration with other healthcare providers.

| The HOPE Project (South West HHS) |

|

South West HHS partners with local councils, Aboriginal Medical Services, the Queensland Police Service, Education Queensland, and the community to deliver the Harmony, Opportunity, Pride and Empowerment (HOPE) Project in Charleville and Cunnamulla. Starting in 2015, the HOPE Project came about after remote communities in Charleville and Cunnamulla decided they needed to address the challenges and disadvantages their young people faced and to provide opportunities to improve their health and social outcomes. The project connects partners and other providers to deliver training, support programs, and initiatives to young people in the communities. This has included art and theatre workshops, workplace skills training, and sport and fitness programs. Health checks and activities to improve mental wellbeing have also featured. The project has also coordinated applications for grant funding from other government agencies. The HOPE Project won the Promoting Wellbeing category at the 2018 Queensland Health Awards for Excellence. |

Queensland Audit Office analysis of information provided by South West HHS, discussions with South West HHS, and publicly available information.

Other government agencies have limited involvement in planning

HHS engagement with other government agencies was generally limited. There are existing cross-government networks (such as the Senior Officers’ Network) that work at a local level to share information, but these are not always focused on health service planning.

The following case study (Figure 3D) gives an example of where the engagement is stronger.

| Community hubs in Children’s Health Queensland HHS |

|

The Yarrabilba Family and Community Place opened in October 2018 as part of the community hubs and partnerships program. This is an initiative where government, non-government organisations, and the private sector work together to deliver facilities and services to meet changing community needs. The Yarrabilba Family and Community Place is a purpose-built hub on the grounds of the Yarrabilba State School. It provides local families and children with access to educational, social, and health-related services, activities, and support. The HHS manages the hub and coordinates program and service delivery in the community. The hub concept came about after local primary schools experienced increased enrolments, which indicated there were many families living in the area with infants and young children. A needs assessment identified that children in the area had a higher social disadvantage, and that the main challenges for the community were isolation, health, and accessibility. The hub is an example of this HHS’s efforts to work with other government agencies to focus on social factors influencing children’s health. The concept design involved the HHS working with various Queensland and Australian government departments, Metro South HHS, Logan City Council, and the Brisbane South PHN. Children’s Health Queensland HHS is leading the evaluation of the program. |

Queensland Audit Office analysis of information provided by Children’s Health Queensland HHS, discussions with Children’s Health Queensland HHS, and publicly available information.

Innovative ideas need to be shared

The Rapid Results Program is starting to achieve benefits

Queensland Health is delivering short-term statewide initiatives through its Rapid Results Program, which began in 2019. The department established a project team that brings together different areas of the health system to deliver different initiatives. These initiatives align with Queensland Health’s strategic direction.

Each initiative has key performance indicators. Several of the initiatives are in the early stages of their implementation, and others are undertaking an evaluation of their success over the first 12 months with a view to transferring them to business-as-usual practice. While the project team has identified promising early signs of success, at the time of writing, it is too early to tell whether they will effectively achieve their goals.

The program has ‘scaled up’ existing work from individual HHSs to share them across the system. One initiative in its early stages is seeking to build on an existing business intelligence tool developed by Children’s Health Queensland HHS, as outlined in Case study 5 (Figure 3E).

| Business intelligence tool for population health data |

|

Children’s Health Queensland HHS delivers statewide services for children and young people. Its health service plans are based on Department of Health data about children and young people in Queensland. This includes data on population health, health service use, and patient activity at the Queensland Children’s Hospital, and data from the Australian Early Development Census. Data can be analysed at a statewide and regional level. In the past, other HHSs requested advice from the Children’s Health Queensland HHS on the health activity of children and young people in their region. Children’s Health Queensland HHS worked collaboratively with these HHSs to understand the demand profile for their region. It then used its data at a regional level to prepare business intelligence packs specific to those HHSs. These business intelligence packs assist HHSs with delivery of services specific to children and young people in their region. The department is adapting this business intelligence concept with its Rapid Results Program. It is in the early stages of delivering a statewide central portal and dashboard of existing and publicly available population and activity data. The data will be used to inform service and infrastructure planning. The portal is available to the department, HHSs, primary health networks, and general practices. Having a central portal for this population and activity data will help to make sure that data being used to inform planning is consistent, accurate, and current. It should also assist those smaller HHSs that do not have data collection and analytics capability or capacity. |

Queensland Audit Office analysis of information provided by Children’s Health Queensland HHS and through discussions with Children’s Health Queensland HHS and Department of Health staff.

Local HHS initiatives are delivering innovation

HHSs are starting to use technology better and share innovations with various partners. These innovations are changing models of care, improving patient outcomes, and making better use of resources. The initiatives we looked at aligned to the My health, Queensland’s future: Advancing health 2026 strategy, or to the health service plans or strategic plans of the HHS. The HHSs had also sought to tailor each initiative to the local needs of their communities.

HHSs have partnered with local organisations and combined funding to deliver primary healthcare strategies. As a result of the partnerships, HHSs and local organisations have developed strong relationships that improve health outcomes for the community. The following case study (Figure 3F) provides an example.

| Emergency and Community Connect and emergency support telehealth in residential aged care facilities |

|

Mackay HHS and the North Queensland PHN established a program called Emergency and Community Connect in collaboration with general practitioners (GPs), residential aged care facilities, pharmacies, and the Queensland Ambulance Service. The program aims to give patients timely care in a suitable setting. It involves coordinated sharing and access of health information between residential aged care facilities, the Mackay HHS emergency department, early assessment teams, and GPs. A key component of the program is Ageing in Place, including telehealth consultations for residents in aged care facilities with their regular GP with support from Mackay HHS emergency department clinicians. Residential aged care facility staff are given the skills to facilitate these video conferencing telehealth assessments of residents and provide ongoing care management. Mackay HHS has undertaken an initial review of these services, which showed that more than half of the patients who used the services were managed at the aged care facility and did not need to be transported to emergency departments. This emergency support telehealth model makes good use of technology to:

The model is being adapted by other HHSs across the state to meet the multiple chronic health needs of Queensland’s ageing population. |

Queensland Audit Office analysis of information provided by Mackay HHS and discussions with Mackay HHS and North Queensland PHN staff.

The sharing of initiatives needs to be better coordinated

There is no centralised function across the whole health system that is being used well or in a coordinated manner to share information. A centralised function would allow HHSs to identify initiatives of other HHSs that could be adopted or adapted to their needs.

The Improvement Exchange, a website developed by Clinical Excellence Queensland (a division of the Department of Health) has the potential to be a centralised system, allowing HHSs to share information about initiatives they have successfully implemented.

As of September 2020, 339 projects were listed on the exchange, with similarities evident in multiple projects. While the large number of projects listed on the exchange indicates that information is being provided for sharing, there was limited awareness of the website among the HHSs we met with and limited control over what was uploaded.

Initiatives are discussed and shared informally through statewide clinical networks (for example, among cardiology specialists) or through existing relationships across the state. These informal networks may not include all relevant stakeholders across HHSs, so the initiatives discussed may not be shared broadly.

The governance review recommended that Queensland Health embed mechanisms to ensure innovations are shared across health services—to build capability in the system and prevent duplication of effort. A recently established forum for HHS executive directors of health service planning is a mechanism that may assist in sharing information on initiatives in the future.

The challenge will be working out the best way to share the information across a large health system.

4. Implementing and evaluating effective long-term plans

This chapter covers how effectively the Department of Health (the department) and hospital and health services (HHSs)—collectively referred to as Queensland Health—undertake, implement, integrate, and evaluate long-term planning.

Long-term planning can help organisations forecast and respond to expected demand and changing demographics. Queensland Health can use it to meet the health needs of the population and improve service delivery. We consider long-term planning to be five years or greater.

We focused on:

- 10–15-year long-term plans that address community health needs, including plans to deliver funding, infrastructure, workforce, and environmental outcomes (enabling plans). A health service plan is more likely to be successfully implemented if it considers the resource needs and engages with teams who can influence these outcomes

- whether enabling plans aligned with other strategic and operational plans

- whether Queensland Health designed, implemented, and evaluated long-term plans to address the projected long-term health needs of the community.

We did not look at statewide services provided by individual HHSs to all HHSs on their behalf (such as heart and lung transplantation services provided by Metro North HHS).

More coordination of long-term planning is needed

The department has prepared two overarching plans that provide strategic direction:

- My health, Queensland’s future: Advancing health 2026 (Advancing health 2026 strategy)

- Queensland Health System Outlook to 2026 for a sustainable health service (System outlook).

The department has also published various statewide plans, strategies, and frameworks. These include:

- plans for services provided across the state (such as respiratory care and cancer care)

- plans for highly specialised services (such as neonatal care and caring for adult spinal cord injuries).

Statewide planning is maturing

The department has only recently developed criteria to decide when to develop statewide plans for services delivered by many or all HHSs. Statewide plans are not in place for all services. For example, there is no statewide plan for orthopaedics; ear, nose and throat (ENT); or ophthalmology—services that were among the top 20 conditions for patients admitted in 2019–20. The department is planning to develop statewide action plans for these services in 2021. Various other departmental statewide service strategies, plans, and frameworks are out of date.

In the absence of these statewide plans, there is a risk that planning by HHSs will be fragmented. This increases the risk of divergent practices across the state, resulting in different models of care.

HHSs can mitigate this risk. In one example, Metro North HHS prepared its healthcare plan for older people who live in north Brisbane two years before the department released the statewide strategy for older Queenslanders. Metro North HHS liaised with the department to ensure broad alignment of strategic direction.

Hospital and health service planning is done inconsistently

The four HHSs we visited have appropriate governance arrangements in place to ensure they each have a long-term health service plan. In the absence of a statewide template, and given their different approaches to planning, the format and content of these plans varied:

- Metro North HHS published an overarching five-year health service strategy in 2015 and has published various five-year health service plans for specific clinical services (such as mental health, cancer care, and emergency) over the last four years. It is currently preparing its new health service strategy.

- Children’s Health Queensland HHS published a 10-year children’s health and wellbeing services plan in 2018.

- Mackay HHS also published a 10-year clinical health service plan in 2018.

- South West HHS jointly published a 10-year health service plan with the Western Queensland Primary Health Network in 2016. The HHS is in the process of revising the plan.

Each plan’s service directions have broad alignment with the Advancing health 2026 strategy. However, the links are not explicit, making it difficult to understand how the plans will contribute to achieving the aims of the strategy.

Enabling plans are critical

Strategies need enabling plans that consider what supports are required to make them work. For example, the design of a new hospital:

- must consider the workforce required to run it

- will impact and be impacted by environmental factors

- needs to factor in adequate funding to construct it, equip it, maintain it, and deliver health services.

Constraints, such as the number of appropriately trained staff or limits on funding growth, will have flow-on effects to other plans and the sustainability of the health system.

Queensland Health commissioned an independent governance review (conducted in 2019) that recommended that the department take account of the different demographic and service needs, and strategic and operational capabilities of individual HHSs and ensure these local nuances are reflected in service agreements and funding models.

Funding variability hinders effective planning

|

Activity-based funding works by calculating the volume and complexity of healthcare provided and multiplying this by a funded rate. |

Activity-based funding has been the main funding model used by the Department of Health to fund 13 of the 16 HHSs. The three remaining HHSs in rural and remote Queensland do not receive activity-based funding. They receive a set dollar amount based on the cost to run their services, as funding under an activity-based funding model would make the services unviable.

The department enters into service agreements with HHSs to agree the funded rate and the volume and mix of services the HHSs will deliver. Nominally, these agreements are for a three‑year period. However, funding amounts have historically only been confirmed on an annual basis. For example, funding for growth in demand for services is determined annually. HHSs reported to us that this limits their confidence to undertake long‑term planning and decision-making for future service delivery.

Queensland Treasury has now entered into a four-year funding agreement (from 1 July 2019) with the Department of Health. This agreement is updated each year and aims to better align funding with health outcomes and facilitate better planning across the system.

The department is strengthening the commitments in the three-year service agreements to provide greater certainty to HHSs about their future funding entitlements.

Incentives and disincentives in the activity-based funding model

Technical efficiency means more activity within the same amount of resources.

Allocative (or dynamic) efficiency considers whether funding is applied to the right mix of services, in the right location, to maximise health and wellbeing over time.

Activity-based funding encourages HHSs to increase their technical efficiency. If a HHS can deliver more healthcare activity with the same amount of staff and with limited increases in other variable costs (such as consumables and energy), it may generate surplus funds to invest in more or different healthcare.

This can increase the risk that HHSs choose to deliver care that attracts funding even though alternative care would maximise the patient’s health and wellbeing in the long term.

The current activity-based funding model does not address allocative efficiency. This is particularly relevant to patients with one or more chronic disease, where continually treating the symptoms of a disease (which attracts activity-based funding) is unlikely to address the underlying cause. Queensland Health, and state governments, are not solely responsible for preventative care. Activity-based funding does not capture all the services that Queensland Health delivers to maintain a person’s health or reduce the risk of further illness.

Many of the health service plans we reviewed included directions to invest funding in services that would help prevent people from requiring hospitalisation and reduce the risk of developing a chronic condition. However, staff were concerned that the type of treatment patients need would not be captured by the activity-based funding model and would not attract funding, making the service financially unviable.

Some Queensland Health staff informed us that the activity-based funding model may not be well understood across the health system. This means services that are eligible for activity‑based funding are not being planned due to the belief that they would not attract funding. An example is the delivery of outpatient clinics in locations outside of a hospital.

Other staff consider activity-based funding to be well suited to the care that Queensland Health provides to many patients in a consistent way, such as elective surgery. This is because it provides an incentive to staff to find ways to deliver the same standard of care using less resources.

The governance review recommended that the service agreement process between the department and the HHSs should be flexible enough to enable each HHS to optimise its performance and deliver sustainable and appropriate health services to meet the needs of its population. This would maximise the incentives for Queensland Health to achieve positive health outcomes for patients rather than just to provide more activity.

Alternative funding models may better target improving health outcomes

One of the Advancing health 2026 strategy’s aspirations is for a sustainable funding model involving contributions from federal, state, and local governments. The main measure of success is implementing new funding models for better connected healthcare and improved health outcomes.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the department began small-scale pilots of alternative funding models under its Rapid Results Program. For example, it is testing a new funding model for kidney care in parallel with the existing model. Queensland Health will review the success of these models when the pilots are completed.

The department is also investigating a hybrid funding model that would be based on the size and needs of the population within each HHS, combined with activity-based funding. The goal is to use the best features from each funding model to improve both technical and allocative efficiency.

Queensland Health does not plan well for how it builds the workforce it needs

|

More than 60 per cent of Queensland Health’s recurrent costs go towards its workforce. |

The workforce is a critical enabler in delivering health services. Workforce planning is therefore crucial to having a sustainable health system.

It is important for Queensland Health to plan how it will recruit staff or upskill existing staff to deliver the services patients expect as the nature of healthcare changes (for example, through expanding the services provided by allied health staff who support rehabilitation and growth in use of technology). Workforce planning also signals to education providers what knowledge and skills graduates will need when they enter the workforce.

From 1 July 2020, the department implemented a new measure to understand the broader labour required to operate hospital and health services. This measure includes all overtime, contractors, and consultants. The department has set a sustainability target based upon this measure. Achieving this target and health service performance targets will be hard for HHSs.

Statewide plans are not in place for all parts of the workforce

In 2017, the department published an overarching workforce strategy that aligns with the time frame for the Advancing health 2026 strategy. It contains objectives and strategies with corresponding measures of success.

Until 2019, the department tracked the progress of initiatives under this strategy. The department also drafted a benefits realisation plan in April 2018, but it has not completed the plan and subsequently tracked progress against the measures of success.

This workforce strategy is intended to guide further planning for different parts of the workforce.

The department has prepared a 10-year statewide plan for its medical workforce (2017), and a strategy for its allied health workforce (2019). Queensland Health does not have a statewide workforce plan for nursing but is in the process of preparing one.

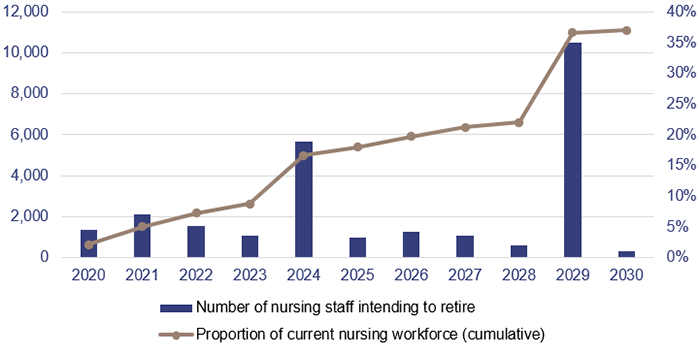

There are emerging challenges for the nursing workforce in the public and private sectors. A large cohort of experienced nurses is expected to retire within the next 10 years. Figure 4A shows retirement intentions for the nursing workforce to 2030, collected through a workforce survey in 2019.

Note: The large increases in 2024 and 2029 represent an intention to retire in five and 10 years (as at 2019). The proportion of the current nursing workforce is a cumulative count of the number of nursing staff who intend to retire by that year.

Queensland Audit Office using Australian Health Practitioner Registration Agency survey data.

At the same time, Queensland Health is recruiting many graduate nurses to prepare for this loss and for expected growing demand.

A large influx of graduate nurses can create challenges, with a decreasing pool of experienced nurses and increasing patient demand to contend with. There is also a growing need for nurses to have more specialised skills to care for patients, such as in mental health. It is important that the department finalises its nursing workforce plan to meet these challenges.

The department has not prepared plans for other clinical areas and critical non-clinical roles.

Not all hospital and health services have prepared workforce plans

Hospital and health services also prepare workforce plans. Two of the four HHSs we visited had workforce plans in place and the remaining two were in the process of developing theirs. HHSs are developing their workforce planning capabilities, as their plans have not been prepared for all critical roles, or plans have only been in place for a short period of time.

Each HHS takes a different approach to developing its plans. Some are centrally prepared through a workforce team; some are prepared by the relevant clinical lead (such as a doctor for the medical plan); others have a framework prepared by the workforce team, which then works with the relevant business area to develop the plan.

The challenge for HHSs is to balance ownership from the relevant business area with consistency and broader organisational or strategic considerations.

Rural and remote areas of the state experience additional challenges, as they have difficulties in recruiting and retaining skilled staff. The department prepared a three-year statewide rural and remote workforce strategy, which was due for review in 2020. The department is drafting a refreshed strategy, scheduled for release by mid-2021. It is unclear how effective the original strategy has been, as the department had not prepared detailed implementation plans, developed performance indicators, or planned how to evaluate the success of the strategy.

Physical and digital infrastructure is growing and ageing

|

Queensland Health had almost $11 billion in buildings and equipment at 30 June 2020. |

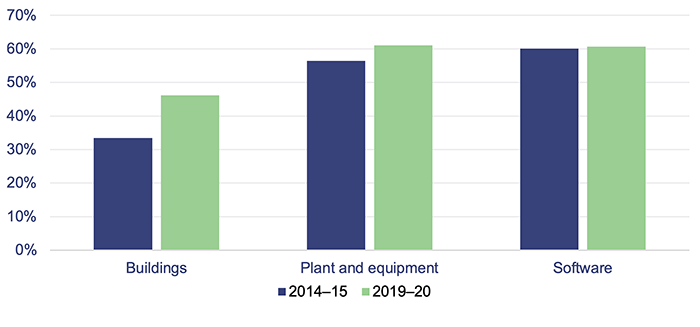

Queensland Health has substantial and growing physical and digital infrastructure. This includes buildings (hospitals and other health service buildings), plant and equipment (medical and other equipment, and computer hardware), and software. In the last five financial years, Queensland Health has spent an average of $700 million each year investing in new or replacement assets.

Figure 4B shows how much utility has been consumed for three asset types recognised by Queensland Health as at 30 June 2015 and 30 June 2020. It shows that these assets—and in particular, buildings—are ageing and there is an increasing need to plan to replace them.

Queensland Audit Office using data from Queensland Health financial statements.

The utility of buildings consumed at 30 June 2020 ranged across HHSs from 23 per cent to 73 per cent. Those HHSs with newer hospitals (such as Children’s Health Queensland HHS) have a much lower consumption rate.

Given the substantial cost and long life of these assets, it is important that Queensland Health effectively plans their design, acquisition, use, maintenance, and replacement.

Strategic asset management plans are identifying significant funding needs

The strategic asset management plan aims to promote stronger alignment between strategic service planning and decision-making about asset management. Each plan must cover a minimum of 10 years and is refreshed annually.

Each entity within Queensland Health prepares their own strategic asset management plan. The department also develops a consolidated plan covering the HHSs and all business units of the department.

We reviewed each in-scope entity’s current strategic asset management plan. As at October 2019, two entities had not yet completed their 2019 plan and two had completed the document in draft.

The department’s most recent consolidated plan is from 2020, covering the period 2020–21 to 2030–31. This plan identified that greater emphasis is needed on ‘sustaining and improving capital to maintain and renew the asset base, as well as providing for sustainable growth to keep pace with service demand’. This is consistent with the feedback we received from Queensland Health staff during our audit.

The state health infrastructure plan may not identify all priority projects

The state health infrastructure plan informs capital investment funding and identifies priority health infrastructure initiatives over the next 10 years. The department updates it annually by:

- collating data from strategic asset management plans and submissions by HHSs and departmental business units (excluding the Queensland Ambulance Service, which makes its own capital budget submissions)

- analysing this data by evaluating it against multiple criteria

- identifying and evaluating Queensland Health’s priority capital investment requirements

- moderating the results to review and confirm the outcomes of the evaluation.

|

HHSs could only submit their ‘top five’ priority projects, meaning some of them may not be considered each year. |

Each year, HHSs and departmental business units make submissions on their ‘top five’ priority projects that are not yet funded for capital investment. This is regardless of the number or value of potential projects they may have forecast in their respective strategic asset management plans.

While the department has applied this process to achieve equal opportunity to have projects funded, some HHSs expressed concern to us that this ‘one size fits all’ approach might not consider their differing circumstances and the availability of funding.

The department prepares and implements ‘lessons learnt’ each year with feedback from HHSs. It prepared a more comprehensive strategic asset management plan model framework for 2019 and future years, including revised templates to help improve the planning process.

Master planning has been refreshed and shows promise

HHSs have recently been undertaking master (longer-term, holistic) planning to define their future infrastructure requirements, identify options for each building asset (including high-level costings), and ensure alignment to their health service plans more clearly. These plans cover a period of 15 years.

Master planning of this nature has not been done consistently in the past across the state, and will assist Queensland Health to better understand its long-term infrastructure needs.

Statewide needs are not analysed and planned for

The planning processes discussed so far in this chapter rely on a ‘bottom-up’ approach to determining the infrastructure needs and priorities of the state. While this allows each HHS and departmental business area to put forward its own local priorities, it does not consider statewide priorities.

This is particularly important, as the decisions of one entity can impact on another in the health system. Expanding the capacity of one HHS might mean another HHS will not need to expand at the same rate (particularly for HHSs in rural and regional areas where patients might otherwise need to travel to Brisbane for healthcare).

The governance review recommended that the department, in consultation with HHSs, develop a statewide capital works plan for Queensland Health to guide investment decisions and inform funding submissions to Queensland Treasury. This will provide a clearer picture of Queensland Health’s full infrastructure needs and the priorities for investment over different periods of time. The government and the department have not yet announced whether they have accepted this recommendation.

The department is currently developing a ‘top-down’ view of infrastructure needs and priorities that will complement the existing ‘bottom-up’ planning approach (which includes the master plans).

It is starting to be supplemented by a new integrated costing tool that assists in determining the operational funding requirements for proposed capital developments. The department intends that this will cover the next 15 years and provide high-level cost estimates for replacing, improving, and building new assets. The department will consult with HHSs to incorporate their perspective, including the results from their master plans.

Asset funding is failing to keep up with need

The Queensland Government provides many different programs that underpin asset funding. These are usually provided in two different ways:

- recurrent allocations, which include the Priority Capital Program, Health Technology Equipment Replacement Program, and minor capital acquisitions. These allocations are typically for the replacement or minor refurbishments of existing assets

- non-recurrent allocations under various programs. These allocations are typically for the purchase of new assets (such as the new Roma Hospital) or for significant improvements to existing assets (such as redevelopment at Caboolture Hospital).

Queensland Health receives its recurrent allocations on an annual basis. This means it does not have certainty about when and how much additional funding will be made available for the replacement or refurbishment of existing assets more than 12 months in advance. This makes it hard for Queensland Health to effectively implement its strategic asset management plans.

The current service agreement requires HHSs to provide asset management planning, capital investment, and maintenance data to the department. The department is analysing this data to determine what funding will be needed.

The recurrent funding allocations are insufficient to meet Queensland Health’s forecast replacement and refurbishment needs. This need has increased in recent years due to the significant investment in new assets that will need to be replaced in the future.

If funding is maintained at current levels, the department’s consolidated strategic asset management plan identifies that measures of sustainability (such as the consumption of assets) will continue to decline. This could result in increased maintenance expenses to ensure assets continue to meet service delivery needs.

Climate concerns are not a key planning consideration

Queensland Health had not actively considered the impact of changes in the climate in its health service or enabling plans, despite the Queensland Government having a whole‑of‑government climate adaptation strategy. A component of this strategy is the Human Health and Wellbeing Climate Change Adaptation Plan for Queensland, produced in 2018.

Health services can be significantly impacted by, and have an impact on, the environment. Changes in climate, such as prolonged heat waves and drought, impact on the types of services health entities need to provide to the community. Health service buildings consume large amounts of electricity to regulate their temperature and run the services within them. Health services also produce large amounts of waste.

The department has teams that are starting to evaluate climate impacts on infrastructure. The department is drafting a climate risk framework. The framework will require all HHSs and the department to develop action plans for reducing their impact on the environment and adapting to climate change. They will also need to identify impacts on service delivery. HHSs currently reviewing their infrastructure master plans are required to include how their infrastructure will respond to environmental and climatic issues over the next 15 years.

Queensland Health has begun to improve energy efficiency within its existing and new infrastructure. The department has undertaken energy audits at eight HHSs and identified sites for potential upgrades to reduce energy consumption and demand and improve energy efficiency.

Planning needs to be more integrated

Queensland Health has not integrated its plans well. The lack of a holistic, documented integrated planning process makes it difficult for it to do this consistently.

Business areas responsible for preparing plans have been siloed in their approach:

- Health service plans have generally been prepared in advance of determining the workforce, financial, or infrastructure implications.

- Infrastructure plans do not always consider the implications for the workforce and do not always consider the recurrent cost implications, although this is improving through the master planning process, and the use of an integrated costing tool.

- Workforce plans do not forecast the funding required to implement them. This limits the effectiveness of each plan and means funding is not provided in the most efficient way possible.

Integrated planning occurs when planning activities and functions link and flow together in a way that aligns with strategic goals and improves performance. It is important for the department and HHSs to work together to integrate their plans, given the interactions that patients can have across the health system and the need to ensure the best use of resources.

The department has been changing its governance arrangements to drive an integrated approach. In September 2018, it established a planning directorate that brought together health system planning, workforce planning, and capital planning. This was changed to separate these teams in November 2019 as a result of the governance review and to better align certain functions (such as co-locating health system planning with funding). It is too early to assess whether these changes are resulting in improved integration and are delivering better outcomes.

The department, in conjunction with HHSs, is implementing a project to guide where and at what level healthcare services should be provided across the state by 2026. The project describes a set of minimum requirements that need to be in place to deliver healthcare across varying capability levels. This includes infrastructure and workforce requirements. The intent is for the department and HHSs to use their agreed target capability levels in asset and workforce planning in an integrated way.

Some of the HHSs we visited have also recently created an integrated planning framework to align their planning activities. Each HHS’s framework describes how its plans should fit together and how they should align with statewide strategies. Given their infancy, it is not yet clear whether these frameworks have assisted in better integrating the plans.

The governance review recommended that:

- the department should develop a comprehensive integrated statewide plan incorporating health service, workforce, and capital works planning; and identifying future service challenges and demand pressures, demand reduction and management strategies, and future models of care

- hospital and health services should ensure their individual strategic planning aligns with the statewide operations and capital plan developed by the department.

Implementation planning needs to occur earlier

As a Queensland Health staff member remarked to us during the audit, ‘Plans don’t work if they sit on your desk.’ They need to be implemented to make a difference.

Implementation planning happens differently across the department and the four HHSs we visited. Most have tried to incorporate it into their annual operational planning processes rather than considering it alongside their long-term plans. Metro North HHS was the exception, with separate implementation plans for its specific clinical services plans.

There are challenges in translating the Advancing health 2026 strategy and the HHSs’ 10-year health service plans into one-year operational plans. This includes understanding what activities need to happen when, what the dependencies are, and how they link to the overall strategy. These plans need an implementation roadmap that bridges the gap between the long-term plans and short-term implementation or operational plans.

The System outlook provides some direction by having three time periods in which actions and outcomes are expected to happen. However, these actions are described in high-level terms and do not make it clear who is responsible. For example, the department and HHSs are listed against every action.

Until recently, Queensland Health only considered how to implement strategies from health service plans after it developed the plans. Many of the plans have words to the effect that ‘an implementation plan will be developed’. This delays implementation of the strategies and creates challenges, as the staff preparing the health service plans may not be the staff who are required to implement them.

In addition, the governing committees overseeing the development of the plan are often not responsible for its implementation. For each plan, Queensland Health does not always identify the right people to oversee implementation of long-term plans.

In the last two years, Metro North HHS recognised the need to start implementation planning earlier and now engages with the staff who will be implementing the health service plan while it is finalising the plan. This approach increases buy-in from staff and makes it easier to transition to the implementation phase.

Queensland Health needs to measure and monitor the effectiveness of its plans

Evaluating a plan’s success is critical to effective planning. It allows an entity to adjust its plan to achieve success, and it will inform the development of future plans.

Entities should determine the evaluation framework before implementing a plan and work out how and when they will determine the plan’s success.

Measuring the effectiveness of a long-term health service plan is challenging. A new strategy can take years to show whether it is working within the target population—for example, lifestyle changes reducing obesity levels. Other factors outside Queensland Health’s control, such as socioeconomic conditions and initiatives from other government and non-government bodies, impact on its ability to precisely measure what effect the strategies are having.

Performance indicators should focus on outcomes

The health service plans we reviewed include performance indicators to describe what success would look like. The indicators are a mixture of:

- input measures—such as the number of joint initiatives between the HHS and other partners

- output measures—such as increased rates of telehealth usage

- outcome measures—such as increased patient satisfaction.

These plans mostly have output rather than outcome measures. While there can be a link between outputs and outcomes (for example, performing certain activities when treating a fractured hip is clinically proven to improve the patient’s outcome), the plans do not make this link explicit. The lack of clarity makes it hard to understand how the outputs contribute to improving the health outcomes of the population.

Almost none of the performance indicators include a baseline level of performance calculated at the start of the plan. The absence of this makes it difficult to track whether performance is improving or not. In some instances, this is because data has not previously been systematically collected in order to set a baseline. In some cases, HHSs spend the first year of the plan collecting data to create a baseline.

The plans often do not set a quantitative target to reach for each performance indicator. For example, the plan does not indicate by how much telehealth usage should increase over the life of the plan for it to be successful. Vague or missing targets make it difficult to track whether the plan is achieving its goals or requires adjustments to its implementation plans.

The enabling plans we reviewed have similar issues. This makes it difficult to track whether the service enablers are successfully contributing to a sustainable health system, including whether:

- the funding provided is sufficient and well targeted

- the necessary workforce is appropriately trained and in the right locations

- assets are performing at the required levels.

In the absence of specific performance indicators for plans, the department and HHSs often rely on the indicators in their service agreements or operational plans to track performance. These sometimes overlap with the measures included in long-term plans, but they are not designed to measure the success of strategies included in those plans.

Queensland Health needs to improve the monitoring of plans

Queensland Health needs to review its reporting arrangements and governance structures to ensure monitoring and reporting of progress against plans. It has recently considered in more detail how it will evaluate each plan as it is prepared.

The monitoring and governance activities vary across the four HHSs we visited. Some have dedicated teams to track plans within specific specialties and others report to their HHS executive or board. Some only report to their boards against the service agreement measures rather than measures in health service plans. This means those HHSs are not tracking whether their health service plans are having the intended impact.

Three of the four HHSs we visited are in the early stages of implementing their current health service plans. Metro North HHS is further progressed. There, a dedicated team monitors the performance of its plans against performance measures and reports on this to executive committees. This enables it to track whether the plans are working and adjust as necessary.

The department has not tracked and measured outcomes from statewide plans. This includes the outcomes expected under the Advancing health 2026 strategy.