Overview

QAO tabled the report Conserving threatened species in 2018, where we made 7 recommendations to the Department of Environment and Science. Our new report examines what progress the department has made in implementing those recommendations, and whether that has improved protections for threatened animals and plants. We cover the 3 key elements necessary to protect threatened species: identifying, assessing and listing, and coordinating and monitoring. We also report on how the department identifies animals and plants at risk, how it assesses extinction risks, and the timeliness around legislative change for listings. We examine the department's progress in delivering a coordinated biodiversity strategy, and whether its strategies are stopping the decline in populations of threatened species.

Tabled 23 February 2023.

Auditor-General’s foreword

Our independent assurance helps parliament, the community, and other stakeholders understand whether public sector entities and local governments are delivering their activities effectively, efficiently, economically, and in accordance with legislative requirements.

Each year in our forward work plan we follow up on a previously tabled report to parliament. Our follow-up audits provide an independent check that management has implemented our recommendations and has addressed the issues we originally raised. They can help entities refocus their efforts and maintain momentum on a program of work. This year, I chose to follow up our report Conserving threatened species (Report 7: 2018–19) due to the adverse findings and the significance of the recommendations we made 4 years ago, and the subsequent impacts of bushfires and floods on critical habitats and animals.

Entities are ultimately responsible for managing and monitoring the implementation of the audit recommendations we make in our reports to parliament. And we expect that audit committees track progress of their implementation. My report on the status of Auditor-General’s recommendations, tabled 31 October 2022, reinforced the important role of audit committees. We would certainly expect entities are advising the committees on the status of the implementation of our recommendations. If entities do not fully address the issues, they will almost certainly still be exposed to risks.

In 2018 I made 7 recommendations to the Department of Environment and Science to improve its governance, processes, and systems to better protect animals and plants at risk of extinction. Four years later, I am reporting its progress in chapters 3, 4, and 5 of this new report.

Queensland is rich with rare and unique native animals and plants. Once gone, they are gone forever, and there is no going back. We have known for many years that losing even a single species can have significant impacts on the rest of the ecosystem, with economic impacts for our agriculture and tourism industries. There are many benefits associated with protecting threatened animals and plants, including helping to maintain biodiversity, and our overall quality of life.

Later this year, I intend to table a report on invasive species, which have significant economic, environmental, and social impacts. They place considerable pressure on native wildlife and, in some instances, have contributed to the decline or extinction of native animals and plants.

Brendan Worrall

Auditor-General

Report on a page

In this audit we assessed the progress made by the Department of Environment and Science in implementing the 7 recommendations from our Conserving threatened species (Report 7: 2018–19). The department has made progress implementing the recommendations, but much more remains to be done, and the improvements to populations of threatened animals and plants are not yet realised.

Threatened native animals and plants

Queensland is home to 85 per cent of Australia’s native mammals, 72 per cent of native birds, and just over 50 per cent of native reptiles and frogs. Queensland has 1,034 threatened species listed under the Nature Conservation Act 1992 (the Act). This is comparable to New South Wales (1,024) but fewer than Victoria (1,998). Of our 1,034 threatened animals and plants, 713 are unique to Queensland.

The Department of Environment and Science, WildNet database.

More animals and plants are classified as threatened

Since the 2018 report, the department has been more active in nominating animals and plants to assess and list as threatened. As a result, 79 more threatened species have been identified and listed. Amending the Act has significantly reduced the time taken to list threatened species, from an average of 506 business days in 2018 to only 56 in 2022.

To ensure state and national classifications are consistent, the department still needs to reassess 366 Queensland animals and plants. The reassessments can increase the department's understanding of the risks species face and allow governments to better target resources to animals and plants of greatest concern. The department prioritised reassessments based on status, distribution, and existing conservation protections.

The department has not set time frames or agreed on the factors that would trigger a reassessment of its classifications. It has proposed an approach to the federal government, other states and territories for a common process for reassessments. Timely and up-to-date information on classifications is important to inform a range of decisions to support inter-jurisdictional cooperation on threatened species.

The biodiversity conservation strategy needs to be implemented

The government released the biodiversity conservation strategy on 7 October 2022. The strategy does not include measures or targets. The department is developing a monitoring framework for the strategy to identify ways to measure conservation of biodiversity across the state. The current lack of measures reduces its ability to monitor outcomes for biodiversity, and demonstrate whether the strategy is achieving the results expected from the resources provided.

The department does not yet have a comprehensive framework to prioritise animals and plants based on risk. It is developing a framework that will consider multiple factors when determining priority species. It has population status and trends available for 10.3 per cent of listed animals and plants. It can evaluate individual recovery programs, but it does not have data on whether overall threatened populations of all 1,034 threatened species are stable, increasing, or declining. It is not feasible for the department to collect data on all 1,034 threatened animals and plants. An approved framework is needed to allow the department to prioritise which data to consistently collect itself or encourage its partners to collect.

1. Audit conclusions

The Australian Government’s recent Australia, State of the Environment 2021 report found that Australia’s environment is poor and deteriorating. Re-establishing or recovering habitats and breeding populations is complex and can take considerable time. It usually requires research, scientific expertise, funding, coordination, and resourcing. That is why identifying threatened species and acting quickly to protect them is important to success. The number of animals and plants at risk of extinction continues to increase.

The department has fully implemented 2 of our 7 recommendations, and it is now more proactively nominating species for listing as threatened and is quicker to list them when needed. The other 5 recommendations are at various stages of progress and further work is needed to effectively address the performance and systems issues that led to the recommendations.

The department advised that several factors have contributed to delays in implementing the recommendations. These include the need to coordinate with Australian, state, and territory agencies; competing priorities; and COVID-19 restrictions. These, combined with devastating bushfire and flood events over recent years, mean that overall, Queensland’s threatened species remain under considerable and increasing pressure.

Only once all recommendations are fully implemented will their effect on improving the long-term management of threatened species be evident.

Listing and assessing species at risk of extinction

The department has listed 79 more animals and plants than there were in 2018. This partly reflects that it is being more proactive in nominating species for listing, as we recommended.

It has begun discussions with other jurisdictions to develop a process for periodically reviewing assessments of classifications. Without a way to keep classifications current, the list may understate the extinction risk to some threatened animals and plants. Regularly reviewing classifications using current data could give the department and the community a more accurate understanding of the threats to our animals and plants.

There is a backlog of species to be reassessed to ensure the Queensland list is consistent with the nationally agreed assessment method. Many (503) Queensland animals and plants assessed prior to 2017 were misaligned with the Australian Government’s Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 or were not assessed using the nationally agreed assessment method. The department has reassessed 137 (27 per cent) of these animals and plants using the agreed assessment method. The department prioritised the sequencing of reassessments based on species status and risk factors. All critically endangered species endemic to Queensland listed under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 have been reassessed.

While all native wildlife is protected under Queensland’s Nature Conservation Act 1992, a species classified as vulnerable in one jurisdiction but critically threatened in another creates confusion. Aligning the classifications of the animals and plants on the Queensland list with the federal list and the lists of other jurisdictions can ensure that all levels of government make decisions consistent with the nationally agreed extinction threat.

Coordinating and evaluating conservation efforts

The department and its partners cannot deliver recovery plans for all 1,034 threatened species. In recognition of this, the department is developing a prioritisation framework to provide a comprehensive basis for the department to target species based on risks. Scientific data and analysis currently inform the development of individual action plans and strategies. The framework could consider the importance of the species for co-benefits with other native species (for example, plants providing habitat for other threatened insects, birds, and mammals), likelihood of success, and effects of invasive species. If effectively designed, and applied, it may strengthen the department’s protected area activities in acquiring the land that will benefit the greatest number of high-priority species. The department has also commissioned researchers to develop a decision support tool to inform the prioritisation framework.

The government publicly released its biodiversity conservation strategy on 7 October 2022. The department did not meet its commitment to parliament’s former Innovation, Tourism Development and Environment Committee that it would release the strategy by the end of September 2019. The biodiversity conservation strategy is aligned with the department’s key conservation and threatened species programs. The government’s other key environmental strategies, such as the biosecurity and invasive species strategies, could be better aligned with the biodiversity conservation strategy. Better coordination and integration of key government strategies could improve results for our environment.

The strategy does not specify measures to determine the data the department needs to collect and monitor, and its evaluation framework is not complete. Also, the strategy does not have targets, which makes it difficult for the conservation sector and broader community to understand if the actions in the strategy have had the expected effect. Appropriate measures with targets can improve accountability to the community for the programs that are funded. The department is developing a monitoring and evaluation framework to identify the measures to allow the department to also set targets.

The government has a range of mechanisms (legislation, strategies, initiatives, and commitments) aimed at protecting habitat, including the Vegetation Management Act 1999 (which it amended in 2018 to improve regulation of vegetation clearing) and the Land Restoration Fund. In 2019–20, about one per cent (4,866 hectares) of the clearing was in areas which have endangered regional ecosystems present, a 4 per cent decrease from 2018–19 (5,077 hectares). While this suggests that these strategies have reduced the rate of clearing of key habitat, it shows that almost 10,000 hectares of land which had endangered regional ecosystems present was cleared between 2018 and 2020. The department collects data annually for reporting purposes and is working to evaluate and monitor ongoing impacts on habitat. More work is needed to further protect habitat.

In 2015, the Queensland Government made a long-term commitment to expand the area of protected land to 17 per cent. There was no time frame for when it would achieve this target. The current proportion of the state’s protected area is 8.3 per cent. In 2021, the median value of Queensland farmland increased 31.3 per cent per hectare since 2020. The increasing price of farmland will place greater pressure on the department’s budget, potentially reducing the amount of land it can afford to acquire.

A key goal of the biodiversity conservation strategy is to support the conservation sector and the broader community to focus on the long-term actions we can all take to protect our threatened animals and plants. To engage the sector, the department must have a clear, evidence-based understanding of the extent of the challenges facing our animals and plants.

Reference to comments

In accordance with s. 64 of the Auditor-General Act 2009, we provided a copy of this report to the Department of Environment and Science. In reaching our conclusions, we considered its views and represented them to the extent we deemed relevant and warranted. The formal response from the Department of Environment and Science is at Appendix A.

2. A guide to reading this report

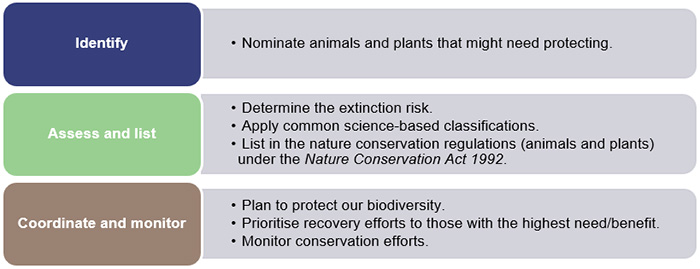

This report is about whether the department’s progress in implementing our recommendations from 2018 has improved protections for threatened animals and plants. We made 7 recommendations to the Department of Environment and Science. We have summarised the original report in Appendix C and the recommendations are listed in Appendix D. This follow-up report is structured around the 3 key elements of:

- Identify: proactively nominating species at risk of extinction to be considered for assessing and listing in the Nature Conservation Act 1992 (the Act) – Recommendation 1

- Assess and list: determining the extinction risks so the nationally agreed classifications can be applied to species (extinct, extinct in the wild, critically endangered, endangered, vulnerable, least concern) and listed in the nature conservation regulations (animals and plants) under the Nature Conservation Act 1992 – Recommendations 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5

- Coordinate and monitor: developing and implementing a comprehensive biodiversity conservation strategy and conservation efforts including monitoring population numbers – Recommendations 6 and 7.

Figure 2A summarises the key elements necessary to protect threatened animals and plants. These were used to structure this report.

Queensland Audit Office.

Chapters 3, 4 and 5 cover our assessments of the progress the Department of Environment and Science has made in implementing the 7 recommendations from our 2018 report.

Chapter 3 reports progress on how the department identifies animals and plants at risk though its nominations process.

Chapter 4 reports on how the department assesses extinction risks consistently with the nationally approved framework. It also reports on the time it takes the department to change the legislation to list threatened animals and plants for protection in the Act.

Chapter 5 reports on the department’s progress in delivering a coordinated biodiversity conservation strategy for the state. It also reports on progress in developing monitoring strategies to inform the department if its strategies are halting the decline of threatened species.

3. Identifying animals and plants at risk of extinction

This chapter assesses the department’s progress in improving how it identifies threatened animals and plants.

Knowing which of our native animals and plants are at risk of extinction allows government, conservation groups, and the community to understand the risks faced and how urgent recovery efforts need to be.

The Department of Environment and Science participates in a range of research and collects evidence itself and with its partners to inform its identification and planning for threatened species.

The department nominates and receives nominations about animals and plants that might be at risk. All native animals and plants are given protection under the Nature Conservation Act 1992 (the Act).

Is the department proactively nominating animals and plants at risk?

|

Rediscovered – Mossman fairy orchid – Oberonia attenuata – previously thought extinct, rediscovered in 2015 and listed as critically endangered in April 2022 by Queensland. Image: A Field, Department of Environment and Science. |

The department is nominating species that might be at risk of extinction more proactively for assessment than it was in 2018. The department has updated and improved its processes to enable and encourage conservation groups to nominate species that might be at risk of extinction. If the department assesses they are at risk, it lists them as threatened under the Nature Conservation (Animals) Regulation 2020 and Nature Conservation (Plants) Regulation 2020. It has promoted better awareness of the process to list species.

In 2018, we found the department relied on the Australian Government or conservation groups nominating species before listing them as threatened or updating the status of those already listed. The list of threatened species was likely to have understated the actual number of species under threat and in need of protection.

Since 2019, there have been 342 nominations: 214 from the department, 63 from the Australian Government, and 65 from non-government entities. Scientists from within the department have also put forward nominations, and Queensland Herbarium staff nominated the most species. The department has also sponsored Humane Society International to produce nominations for several high-priority reptiles. Nominations go to the Species Technical Committee for consideration.

Not all nominations have resulted in species being listed. Some did not meet the criteria for listing or required more information, and others resulted in the status of already listed species being changed. There are now 1,034 threatened species listed − up from 955 when we completed the original audit.

Nominations from the community

In 2018, we concluded that the department was not encouraging Queensland’s large community of conservation researchers and stakeholders to nominate animals and plants at risk of extinction.

The department has made the nomination process more transparent. Information is now freely available on its website.

The department updated the forms for nominating a species and made them publicly available on its website in 2019. It has now published:

- species nomination forms and listing processes to inform and educate potential nominators

- the terms of reference of the Species Technical Committee and make-up of the committee (for transparency and accountability)

- past and proposed dates of the Species Technical Committee meetings to inform the public when species are to be assessed

- lists of finalised assessments of Queensland species by the Species Technical Committee that have been recommended to the state Minister for the Environment and the Great Barrier Reef and Minister for Science and Youth Affairs

- lists of updates made to the wildlife classes under the Act, as approved by the minister.

|

We interviewed representatives from 5 key conservation groups located in Queensland. They all agreed that the nomination process is easier to understand and clearer to follow. |

4. Assessing animals and plants at risk of extinction

This section covers the department’s progress in improving the assessment and listing of threatened animals and plants.

All native animals and plants are protected under the Nature Conservation Act 1992 (the Act). Listing threatened animals and plants classifies their risk of extinction category. It adds further protections, such as additional restrictions (permits) on people taking them from the wild and clearing their habitats.

Periodically confirming an animal’s or plant’s classification can ensure that the extinction risk has not changed because of population changes or habitat loss. New Zealand reviews classifications for listed species every 3 years.

In 2013, the federal Senate Standing Committee on Environment and Communications found the inconsistencies in each jurisdiction's assessment methods were creating significant uncertainty about the overall scale of the extinction threats. The committee also found it was diminishing governments’ abilities to target their limited resources effectively and efficiently to animals and plants, and habitats of greatest concern. It recommended developing a nationally consistent assessment method – now known as the common assessment method.

Is the department assessing animals and plants at risk of extinction consistently and listing them quickly?

The department is actively working to meet its commitment to assess newly identified animals and plants consistently with the common assessment method.

The common assessment method – This is a nationally consistent way for assessing and listing threatened species. It means that all occurrences of the species within Australia are considered in the assessment and classified with the same categories (extinct, extinct in the wild, critically endangered, endangered, and vulnerable). It is intended to reduce confusion around the conservation status of nationally threatened species. It was signed by all Australian state, territory, and federal governments (except South Australia) in 2019.

The department has prepared a procedural guide that provides the overarching governance elements and a plan for listing threatened species. The guide documents how the department coordinates the process of listing threatened species in Queensland to comply with the common assessment method. It includes improved governance arrangements for implementing the Queensland threatened species listing process and the common assessment method.

The department introduced 2 new classes of wildlife in the Act in August 2020, and its assessment categories are now consistent with those adopted by most other Australian jurisdictions. It also redesigned the nomination form in December 2018 to capture the information required for compliance with the common assessment method.

The department is listing animals and plants assessed as threatened quicker than it was in 2018. This means animals and plants should be receiving increased protections under the Act quicker than they were previously. The department is also assessing species consistently with the agreed common assessment method.

However, the department has not finished reassessing 73 per cent of Queensland animals and plants using the nationally agreed assessment method. In 2015, the Australian Government identified that this lack of consistency could lead to confusion and duplication of effort. Reassessing these animals and plants is a commitment under a memorandum of understanding with the Australian Government. The department advised that undertaking the reassessments requires a review of scientific information for each species, which takes time and resources.

The department has strengthened its accountability and oversight for threatened species. It allocated this responsibility to the new Threatened and Protected Species Steering Committee (which merged into the Biodiversity Strategy Steering Committee in late 2020). This committee focuses on the broader strategic biodiversity issues including threatened animals and plants and interactions across the work of the department.

Interstate consultation

The department is engaging and consulting more with its interstate counterparts. Representatives from the department regularly participate in the monthly National Common Assessment Method Working Group meetings. This group facilitates cooperation, communication, information sharing, process development, and implementation between signatories of the memorandum of understanding. Under the common assessment method arrangements, jurisdictions notify each other if they are going to lead a nomination and request data from any other state. The department has formal procedures to respond to consultation or requests for information from other states and territories and the Australian Government.

Threatened species program plan and budget

Since 2020, the department has progressed the activities it assessed it could deliver within its existing resources. The rest relied on obtaining an additional budget allocation, which it received in 2022. It was allocated an additional $14.7 million (plus $24.6 million specifically for koalas).

In 2018, it had no overarching plan for its threatened species activities. It was not able to monitor major project deliverables, milestones, or activities, or to determine if it had the resources it needed.

The department developed a new threatened species program in 2020. The program details the strategic direction and coordination for threatened species management in Queensland. It also maps all the linkages between its projects and the intended outcomes (program logic) for threatened species and their habitats.

In 2020, the department identified that without additional funding and/or re-prioritising other departmental activities, it only had sufficient funding to deliver 57 per cent of the new program’s activities.

In 2022, the department received $14.7 million for the threatened species program for the next 4 years. This included funding to implement the recommendations from our original report. The department has updated its program implementation with the additional funding. It has advised us that with this funding, and by reprioritising its other activities, it now has sufficient funding to deliver all the recommendations from the audit and the broader threatened species program.

The department also received $24.6 million specifically for the South East Queensland Koala Conservation Strategy.

The department needs to review classifications periodically

The department has begun discussions with the Australian Government and other jurisdictions to develop a process for periodically reviewing assessments of classifications. As the common assessment method is a nationally agreed approach, periodic changes to classifications need national agreement.

In 2018, the department did not have a process to periodically update the status of species already listed. It still does not systematically review current information to assess whether the status should be updated after a set period. As a result, the extinction risk for many animals and plants may rely on outdated information.

In September 2022, the department provided a draft supporting paper for discussion to the Common Assessment Method Working Group meeting. This is because Queensland cannot have its own process which would differ from other states and territories as per the common assessment method. The paper Triggers for updating conservation advices and/or listing assessments provides a snapshot of the triggers for listing reassessments or updates to conservation planning documents. It is unlikely that agreement on reviews of classifications will be achieved quickly, given the current backlog of assessments of misaligned species the federal government, states, and territories are addressing. Australia does not have a periodic review cycle. New Zealand’s review cycle is every 3 years.

Classifications of some species may be reassessed if monitoring by the department or its partners identifies a change in population or habitat. Not all species are being monitored, and without a systematic way to keep classifications current, animals or plants assessed as vulnerable 15 years ago could now be endangered or extinct. Setting periodic reviews or identifying the specific triggers for a review could give the department and the community up-to-date information on the status of threatened animals and plants and assist with prioritisation.

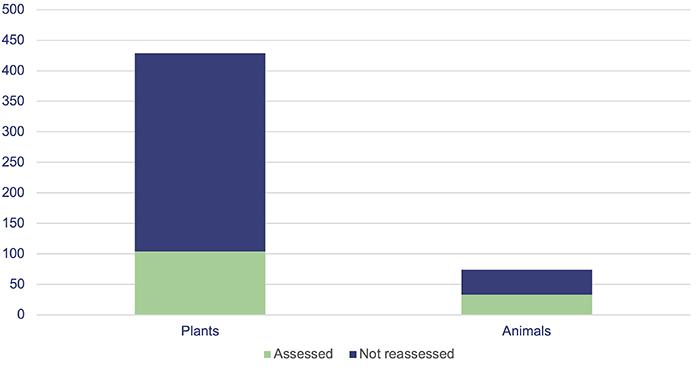

Need to clear backlog

In 2019, the department reviewed the species listed in the Nature Conservation Regulations and identified 503 Queensland animals and plants that needed to be reassessed. This was because they were misaligned with the Australian Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 or were not assessed using the new common assessment method. It has reassessed 27 per cent of these animals and plants.

In 2018 we found that, while the department had begun to reassess misaligned animals and plants to be consistent with the common assessment method, it had not dedicated any resources or developed a plan to estimate the resourcing and time needed to reclassify animals and plants.

|

Misaligned – Southern snapping turtle – Elseya albagula – previously listed as Endangered in Queensland and Critically Endangered nationally. Image © [2019 Bruce Thomson], used under license from Auswildlife.com. |

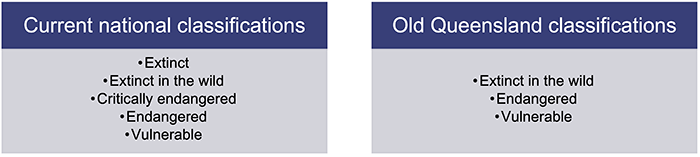

Figure 4A compares the old Queensland classifications with the current nationally agreed ones from the common assessment method.

Queensland Audit Office.

The primary aim of the common assessment method is to reduce confusion about the status of listed species under different jurisdictional lists. A common national approach can reduce duplication of effort in listing assessments. As species are not limited to state boundaries, it is important that protection activities are coordinated and consistent across jurisdictions.

Figure 4B shows the progress the department has made in clearing the backlog of Queensland unique animals and plants that have classifications not consistent with the national common assessment method or have not been assessed using the common assessment method. The department has applied a prioritisation approach to ensure it reassessed the most at risk species first. It has completed its reassessment of all the critically endangered species endemic to Queensland listed in the Australian Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.

It has now reassessed 27 per cent of the animals and plants, so their risk of extinction classification is consistent across jurisdictions. However, after 4 years, there are still 366 Queensland animals and plants to be reassessed.

Note: In addition to the above, the department has identified a further 29 species (23 plants and 6 animals) that are not unique to Queensland. The department has agreed to take responsibility for reassessing them as these species have the vast majority of their population in Queensland and there is a relatively small distribution of those species in another jurisdiction.

Queensland Audit Office, from the Species Technical Committee’s reports.

The department is listing threatened animals and plants for protection more quickly

|

Mt Elliot Leaf-tailed gecko – Phyllurus amnicola – listed as vulnerable in January 2022. It took 56 days to list it in the regulation. Adobe Stock image. |

The department has reduced the average time to change the regulation in the Act from a high of 506 business days in 2018 to 170 business days in 2021. The department may delay progression of the regulation changes for the listing of animals and plants if there is another set of committee recommendations expected within 3 months. In 2021, the department delayed listing in the regulation the animals and plants from the February recommendations until the next set of recommendations were completed in April. Both lots of listings occurred in November.

The 2022 figures are not yet complete, but the department listed the first batch of 2022 animals and plants in 56 business days. This provides protection under the Act much more quickly for animals and plants (and their habitats) assessed as threatened. The 56 business days includes the time from when the committee makes its recommendation to the minister to when the regulation amendments to list the species come into effect.

In 2018, we concluded that animals and plants were not getting the protection they needed, as it took a long time to list them. In some cases, it took many years to change the regulation and list those already assessed as threatened.

In February 2020, the department amended the Nature Conservation Act 1992 (the Act). It now requires the minister to decide on animals and plants listing within 30 business days of receiving a recommendation from the expert scientists on the Species Technical Committee.

By comparison, after each assessment by the Australian Government’s Threatened Species Scientific Committee, the federal minister has 90 business days to decide whether to update the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.

Contributions from the public for existing assessments or information to inform future assessments

The department does not encourage public input into the existing nominations the Species Technical Committee is considering. This has not changed since 2018, when we concluded that a lack of transparency around the assessment process was not promoting public trust in the assessment process. Individuals could not trace a nomination and assessment through to its listing in the regulations.

The department is still not publishing online nominations the Species Technical Committee is assessing, so the public cannot submit further information that may assist with the assessment. It is also not publishing the committee’s assessments and recommendations, with supporting scientific evidence to inform future nominations.

The department advised us that it considers that publishing nominations the Species Technical Committee is currently assessing is problematic, as often the committee:

- requests or recommends changes as part of the assessment process based on the scientific evidence provided

- may defer or reject a nomination if it is incomplete

- may ask nominators to seek further information from identified relevant experts

- has not vetted or conducted quality control on the nomination.

The department’s view is that only a limited number of stakeholders hold scientifically collected data that can contribute to the nomination of a particular species. It considers that most authors of nominations would ensure that they consult with the relevant species experts. The department’s view is that the Species Technical Committee is well represented with expert scientists who can seek further advice on nominations if required.

|

We interviewed 5 representatives from key conservation groups located in Queensland. They were not concerned about not having input into assessments of animals and plants nominated by other conservation groups. The focus of individual groups was on the animals or plants they had nominated themselves and what they could do to improve the evidence to support their nominations. |

Providing conservation groups and the community a greater understanding of the information used in the assessment process would help them ensure their own nominations are complete.

Community ownership and engagement is one of the department’s key outcomes in the threatened species program. Now that the department has increased the capacity of the Species Technical Committee, it may benefit from revisiting opportunities for greater input from the broader community and conservation and research groups.

5. Coordinating and monitoring conservation efforts

This chapter covers the department’s progress in ensuring the state’s biodiversity is protected.

Biodiversity is short for 'biological diversity'. It includes the variety of species of all living things, from humans, animals, plants, and fungi to the tiniest organism. They are all intertwined and connected, rather like a net. The more biodiversity there is, the stronger an ecosystem is, because small changes will have less of an effect on its stability.

Biodiversity is a major contributor to the economy. It provides us with fresh air, clean water, nutrients for plant growth, and crop pollination. For example, the value of crop pollination to agriculture in Australia is estimated at $1.2 billion per annum.

Biodiversity also has intrinsic value: our native animals and plants contribute to our sense of cultural identity and enrich our lives.

A biodiversity conservation strategy needs to be implemented

The Department of Environment and Science has now released its biodiversity conservation strategy. The department completed an internal-to-the-department version of the strategy 3 years ago and has been using it to guide department delivery of programs, but the public version was not approved for release until 7 October 2022. It now needs to work with conservation groups, other departments, and the broader community to fully implement and integrate the strategies and headline initiatives. At present, the government’s invasive species and biosecurity strategies are not fully aligned with the biodiversity conservation strategy.

There were examples of the department monitoring and reporting conservation actions funded by government and its partners. An absence of measures in its strategies reduces accountability for the broader strategies; its staff and partners do not know what 'good' looks like or how their success will be measured. Since the department has not yet set targets, it cannot demonstrate what results it expects the strategy to deliver with the resources provided. The department is developing a monitoring and evaluation framework to identify ways to measure progress against the strategy.

Few animals and plants listed as threatened have recovery plans in place. Given the number of animals and plants at risk, the department cannot develop recovery plans or monitor the population trends of them all. It needs to prioritise its investment so it can focus its activities. In this way, it can achieve the most effective balance of actions to protect habitats, mitigate threats, and reduce species decline. Work is underway to ensure this can be done on a comprehensive basis through a prioritisation framework.

A new threatened species program and biodiversity conservation strategy have now been released

In 2020, the department developed and released its new threatened species program, which responded to the original audit’s concerns regarding the lack of a coordinated approach. The new program is on the department’s website, and the funding received in 2022 aligns to this plan’s delivery. The department’s overarching biodiversity conservation strategy, released on 7 October 2022, contains its key strategies and programs. It communicates to other departments, researchers, and the community what the department is trying to achieve to maintain the state’s biodiversity – and why.

In a submission by the department to the parliament’s former Innovation, Tourism Development and Environment Committee dated 5 July 2019, the department wrote ‘The overarching strategy is planned for release by the end of September 2019.’

The strategy (which was published on 7 October 2022) aligns with its Threatened Species Program 2020–2040 and Protected Area Strategy 2020–2030. It clearly links the key Queensland legislation, strategies, and initiatives that complement and contribute to delivering biodiversity outcomes in Queensland. However, the government’s other key strategies affecting the environment such as for invasive species or biosecurity are not fully aligned with the biodiversity conservation strategy. There is an opportunity to better coordinate governance across government for these strategies to ensure approaches are integrated and consistent.

|

We interviewed 5 representatives from key conservation groups located in Queensland. Four were unaware of the department’s biodiversity conservation strategy at the time and raised concerns that it was not available to inform their planning. |

The impacts of conservation efforts are not consistently evaluated

The department does not have a completed monitoring and evaluation framework for the biodiversity conservation strategy; this work is underway. Until this is in place, it cannot effectively evaluate and report on progress towards achieving the goals outlined in the strategy. When complete, the evaluation framework will be able to guide the data collection.

In 2018, we found the department was not sufficiently evaluating the state’s conservation activities and the impact on threatened animals and plants to inform future delivery and investment. It was, therefore, difficult to assess whether management of, and investment in, conservation activities had been effective.

The department has now made progress in improving its ability to evaluate its threatened species program by:

- engaging a Queensland university to develop an evaluation framework − expected to be completed in December 2022

- developing a model to show how the different components of the program need to work together to achieve its long-term goals (a program logic model).

Agreed targets are needed to support greater accountability

Monitoring is more efficient and effective if it is guided by clear outcomes and indicators. The biodiversity strategy does not currently contain any SMART (specific, measurable, actionable, realistic, and time-bound) targets.

The department’s draft evaluation framework will improve its capacity to collect data and measure its progress for threatened animals and plants. At present, it has not set targets to clearly show what is expected to be achieved and by when. For example, the Australian Government’s The Threatened Species Action Plan 2022–2032 released in October 2022 includes a target that all priority species are on track for improved trajectory by 2027.

Previously, in its 2017–18 annual report, the department reported on the percentage of the threatened species targeted under recovery plans that maintained their classification. Its target was 95 per cent, and it reported that 100 per cent maintained their classification.

It discontinued this performance measure as the recovery plans at the time were administered by the Australian Government. Given that the department has now developed its own recovery action plans and recovery action groups and has adopted many of the federally developed plans, it could reconsider developing its own measures. For example, it could report on the percentage of threatened species funded by its recovery plans that maintain or increase their population.

Relatively few threatened animals and plants have specific plans in place

The Australian Government develops recovery plans for animals and plants that occur across multiple states and territories. The department, through its threatened species program, also now develops recovery action plans for animals and plants that are unique to Queensland.

There are now 78 recovery or recovery action plans in place, covering 129 threatened animals and plants (12.5 per cent) that occur in Queensland.

The Australian Government, the department, and other jurisdictions coordinated these plans, as many of these animals and plants also occur in other states and territories. Of these, the department contributes to 30 active recovery groups, where departmental staff work with local conservation groups on recovery plans or actions for specific animals or plants.

The department was not able to provide a complete listing of all recovery efforts, as many of its activities will have direct and indirect impacts on threatened species protection and recovery. New funding is committed to develop further recovery action plans for key priority species.

The department developed 3 new conservation or recovery action plans for uniquely Queensland animals and plants. It intends to complete another 8 by the end of the year. It is also implementing projects that cover multiple species. Seven hundred and thirteen threatened animals and plants are unique to Queensland.

|

Recovery plan – Northern hairy-nosed wombat – Lasiorhinus krefftii. It was listed as critically endangered in 2018; a recovery action plan was approved in 2022. Queensland Government Image. |

In 2018, we found the department was managing recovery/action plans for 30 threatened animals and plants. The department is continuing to develop recovery plans. Its goals are to:

- develop recovery action plans and threatened-species recovery teams for 20 priority animals and plants by June 2023 and 50 more by December 2025

- deliver recovery actions by Indigenous Land and Sea Rangers groups, with 5 new contracts by June 2024.

Recovery action plans are not a legislative requirement under the Queensland Act. However, the department advises it is adopting recovery planning as part of its new threatened species program. It has recently prepared the first Queensland plans for the northern hairy-nosed wombat, and marine turtles (Marine Turtle Conservation Strategy). The department is supporting implementation groups (local conservation groups, non-government organisations, researchers, and volunteers) to actively recover these animals and plants.

Case study 1 provides an update of the case study from our original 2018 report of a conservation advice for a threatened animal that was once found across inland eastern Australia. This is an animal the department is monitoring, and it is subject to research for consideration as a priority species. It shows how a coordinated recovery plan with involvement of multiple partners can help stop the decline of threatened species populations. The actions to protect the existing population in Queensland have allowed new colonies to re-establish in areas where they used to occur. Populations have continued to increase since the 2018 report.

The recovery plan and actions were developed in partnership with:

- the Department of Environment and Science

- the New South Wales Office of Environment and Heritage

- the Australian Department of the Environment

- conservation groups and zoos

- Indigenous groups and land councils.

| An update on the bridled nailtail wallaby – Onychogalea fraenata | ||

Threats that have contributed to the decline of the bridled nailtail wallaby in Queensland include:

Recovery actions In 2016, the Australian Government's Threatened Species Scientific Committee published a conservation advice outlining conservation and management priorities for the species including:

Population stability Initial population estimates for this species in 2007 were 70 wallabies in Taunton National Park and between 70 to 100 on the Avocet Nature Refuge. By 2017, numbers in Taunton National Park had increased to 392. Conservation groups estimate that there are approximately 1,500 individuals in Taunton National Park in Queensland, and the Avocet Nature Refuge remains stable with around 100 individuals. Populations have also been re-introduced in New South Wales. |

Queensland Audit Office, from Department of Environment and Science’s reports.

Queensland’s protected areas

Habitat is a key factor in supporting the recovery of threatened species (as well as having a range of cultural, economic, and social benefits). Many threatened species are found in national parks and other public protected areas and are highly or entirely reliant on these areas for their survival. The government has a range of mechanisms, strategies, initiatives, and commitments aimed at protecting habitat.

In 2015, the Queensland Government made a long-term commitment to expand the area of land protected to 17 per cent as part of a national agreement with the United Nations. In 2018, 8.2 per cent of Queensland was protected. By December 2022, the area protected was 14.3 million hectares, or 8.3 per cent of Queensland's landmass – a 0.1 per cent increase.

The Queensland's Protected Area Strategy 2020–2030 aims to increase the protected area system to conserve critical habitat for threatened species. In its 2022–23 Queensland Budget, the government committed $262.5 million over 4 years for land acquisitions and capital works to increase Queensland's public protected area estate.

Other government approaches for habitat and ecosystem protection include vegetation management and land restoration activities. Reducing habitat loss will improve the biodiversity, protection, and recovery of threatened species.

In 2018, the Queensland Vegetation Management Act 1999 was amended to improve regulation of the clearing of vegetation (outside protected areas) in a way that prevents the loss of biodiversity and conserves vegetation that is classified as:

- an 'endangered' regional ecosystem or

- an 'of concern' regional ecosystem or

- a 'least concern' regional ecosystem.

In December 2022, the 2019–20 Statewide Landcover and Trees Study (SLATS) was released, showing an overall decrease of woody vegetation clearing activity across the state from 2018–19. This is the most recent data. New scientific methodologies and technologies for SLATS were introduced for the 2018–19 monitoring period, changing the way that woody vegetation is monitored. Therefore, direct comparisons with previous results up to and including 2017–18 are not possible.

In 2019–20, 74,305 hectares of the clearing activity was in areas that contained 'of least concern regional ecosystems' and 4,866 hectares in areas which have 'endangered regional ecosystems' present. While this represents a 58 per cent and a 4 per cent decrease from 2018–19 in those respective areas, there was almost 10,000 hectares of clearing activity in areas that have endangered regional ecosystems present between 2018–19 and 2019–20.

The Land Restoration Fund allows the department to support landholders, farmers and First Nations peoples with land management activities that store or avoid carbon emissions from the landscape. The fund can also support other benefits such as improved biodiversity and protecting threatened species.

Does the department effectively monitor and report on population and trends for threatened animals and plants?

The department and its partners are currently monitoring the populations of 106 of the 1,034 animals and plants listed (10.3 per cent). It is actively monitoring trends for 11 of these for the national threatened species index.

Indicators of the success or failure of current recovery actions rely on changes in population trends. The department does collect population data on some species but has not finished its prioritisation framework. Without data on increases or declines in priority populations, the department and its partners cannot determine if they are optimising the use of resources, and it cannot change or adjust priority programs that are not working.

Effective monitoring by the department and its partners is vital to inform appropriate management actions and better conservation outcomes for our threatened animals and plants.

The department has not finished developing its prioritisation framework

The department has not finished developing a prioritisation framework to ensure its limited resources are used to achieve the best results.

In 2018, we found the department was not using a method to prioritise which animals and plants it should be monitoring. It selected animals and plants for monitoring based on knowledge within the department (for example, marine turtles); others due to their iconic value (such as the koala, wombat, and bilby); and others because of significant work done by external conservation bodies (for example, on seabirds and shorebirds).

In 2019, the department undertook its own jurisdictional review of prioritisation frameworks. In 2021, it engaged an external science institution to co-develop one for Queensland. The project is in 2 parts, with delivery dates of December 2022 for the first tranche of priority species and June 2023 for the completed prioritisation framework.

A comprehensive prioritisation framework will allow the department to strengthen the scientific approach to considering the species values of animals and plants. The prioritisation framework will consider co-benefits for other species and the likelihood of success for recovery through a decision support tool. The cost of monitoring population trends is important, as some animals and plants may be relatively expensive to monitor based on their geographic distribution or habitats.

Taking a range of factors into consideration to inform its monitoring program can ensure the department takes a balanced approach to allocating its limited resources. It may be better value, for example, to monitor 5 priority animals and plants that are easy to count, and have a good chance of recovery, than one that is hard to monitor and for which recovery efforts are unlikely to have much impact.

Data management and access need to improve

The department has identified the gaps in its data management and is developing a plan to address the difficulties its staff and other researchers have accessing data. The new system will not be in place until 2024.

Access to comprehensive data is essential to threatened species protection and conservation efforts. The department needs to improve its collection and sharing of information on threatened animals and plants – between its staff, conservation partners, and the public. It does not know all the data it has, and what it does have is not easily accessible. This means it bases some of its decisions on incomplete or out‑of‑date data.

The central database for threatened species projects needs improvements

The department is not able to effectively coordinate information gathered on threatened species activities. The WildNet database, built in 1997, is its centralised data platform. It relies on manual processes for curating, loading, managing, and sharing information. This makes it difficult for internal and external researchers to discover and share information on animals and plants that are at risk.

In 2018, the department did not have agreements or processes in place for gathering and processing threatened species data into a central database to improve its monitoring and reporting.

Many different parts of the department contribute to the protection of, mitigation (of threats to), and recovery of threatened animals and plants in various ways. But the department does not collate information on the populations of threatened animals and plants being undertaken by external organisations within the state. Therefore, it does not know the recovery outcomes of our threatened animals and plants.

The department does not have any data management protocols to guide how data on animals and plants is stored, managed, and distributed. Not all teams that undertake threatened species activities provide monitoring data to the department’s Science Division, which manages WildNet (the department’s database for recording wildlife sightings and listings in Queensland).

As an initial step towards developing a framework for monitoring and reporting of threatened species, the department started compiling an inventory of threatened species projects across its different divisions.

In late 2020, the department developed its WildNet System Strategy (2020-2025) to prioritise business demands and inform upgrades. The strategy was developed in late 2020. It provides a set of focus areas and a roadmap for modernisation activities. Modernising WildNet includes:

- initiatives to consolidate biodiversity systems and new data management capabilities and infrastructure through the Accelerating Science Delivery Innovation Program

- a biodiversity data repository, funded from The Australian Government Digital Environmental Assessment Program.

The goal is to design and implement a comprehensive data platform for threatened species by the end of 2024. This could enable the department to consolidate threatened species data in an online repository, giving it an interactive, visual tool to perform data analytics.

There is a backlog of wildlife data

The department’s database for recording wildlife listing and sightings in Queensland is still not complete or up to date. The department has a significant backlog in information (approximately 10 million records) that it needs to upload. As a result, this information is not readily available to inform decisions.

WildNet does not have the functionality to easily show trends or changes in population abundance over time for all threatened species. Where it does collect monitoring data on species, the department has provided it to the Threatened Species Index, which provides nationally comparable measures of change in the relative abundance of Australia’s threatened and near-threatened animals and plants. To date, the department has contributed monitoring data on 11 animals to the index and no plants.

There have been some improvements in data collection and access

The department has been able to access some federal funding to improve the way it collects and manages some of its data. The bushfire species recovery program and turtle map are examples.

In 2021, the department launched the online marine Turtle Breeding and Migration Atlas (TurtleNet), which was the work of department staff in collaboration with its international partners studying migratory turtles. The atlas shows decades of information of distribution and abundance of marine turtles and migratory patterns.

In 2019–20, Queensland experienced a severe bushfire season. More than 8,000 fire incidents were recorded in the state, burning more than 7.7 million hectares of land, including habitats of 648 threatened plants and animals. Case study 2 discusses some federally funded innovative approaches the department took regarding data collection to support recovery efforts.

| Using satellite imagery to identify impacts of bushfires |

|

Bushfire species recovery program In February 2020, the department received $1.5 million in emergency funding from the Australian Government to deliver the Queensland bushfire recovery program. The department has delivered priority threatened recovery actions for 25 fauna, 27 flora species, and an unidentified number of native invertebrates across the following 4 protected areas in southern Queensland:

Satellite imagery The department collated and integrated post-fire data from remote satellite imagery and Queensland Herbarium ecosystem mapping to identify areas of the greatest ecological impacts to fire-sensitive wildlife. The spatial assessment of the fire severity and type of vegetation burnt provided data over a much larger area than would have been possible from field surveys only. It used the Queensland Herbarium’s potential habitat modelling for 376 threatened species in Queensland, to support scientists and park managers to better direct on-ground recovery actions (such as species surveys, weed control, or pest control) and protection of species. It conducted assessments by undertaking surveys of animals and plants using a range of techniques (for example, survey transects, acoustic recorders, and camera traps) to detect priority threatened species in burnt habitats. It also used surveys to clarify spatial distribution, relative population size, and breeding status where possible. Outcome The department completed phase 1 of the recovery program in June 2021. The recovery actions delivered so far have supported actions for 25 threatened animals and 27 plants and their habitats. Some of the animals covered by the recovery actions included:

|

Queensland Audit Office, from the Department of Environment and Science’s reports.

The department does not systematically report on its progress in conserving threatened animals and plants

The department currently does not systematically report information about the populations of threatened animals and plants. This reduces its ability to demonstrate the effectiveness of its recovery actions. It also reduces the availability of key scientific evidence for conservation groups and researchers to conduct their recovery efforts.

The department is working with its partners, such as researchers, universities, regional natural resource management groups, and local and federal governments. These partners also contribute to the knowledge of threatened species. As some of this information is stored in individual external partners’ systems, the department needs to identify what data is held and coordinate how it can collect the data for analysis.

In 2018, we found the department’s lack of systematic and reliable monitoring of threatened species also meant it could not detect population changes or quantify the efficacy of its actions. As a result, it often could not show how it used its resources to achieve the best conservation outcomes.

The department does report on its protection and recovery activities. These are in its:

- State of the Environment Report (SoE) (2020) – which includes information on its activities for threatened animals and plants and ecosystems. The SoE reports on the total number of changes to listings of threatened species and links to a current list of threatened species and their status. It does not include information on whether the populations of animals and/or plants with recovery plans are now stable, declining, or improving. There are no measures to allow the department to show its efforts are effective in protecting threatened species

- Report on the administration of the Nature Conservation Act 1992 – which lists amendments to legislation, protected areas, wildlife and habitat conservation, conservation orders, and offences and prosecutions

- annual reports – which report activities conducted against objectives and service delivery statement service standards.

The department now also reports on its annual progress against targeted outcomes in the South East Queensland Koala Conservation Strategy 2020–2040 – reported for the first time in 2022. This strategy outlines the actions across governments, industry, and the community. The report includes critical targets to:

- stabilise South East Queensland koala populations

- increase (net gain) habitat areas

- restore habitats (10,000 hectares)

- reduce threats (10 programs to reduce disease, injury, and mortality).

However, the department did not report any progress or baseline data as the 4 targets were recorded as ‘work in progress’ for this first report. The department does not have targets for its other conservation actions and strategies. The department advises that there are challenges with accurately identifying annual changes in koala habitat areas due to the lag in receiving current satellite imagery and the significant work involved in processing them.

Monitoring and reporting in response to recovery actions does not occur on an annual basis for most threatened species. No targets are set to stabilise populations of other animals and plants.

The department’s website provides information on recovery activities for a few select threatened species projects (for example, the bridled nailtail wallaby, greater bilby, nangur skink, northern hairy-nosed wombat, southern Cassowary, Richmond birdwing butterfly, capricorn yellow chat, and marine turtles). Population data is available for some of these animals.