Overview

Organic waste, such as food and garden waste, makes up about half of what Queensland households throw away in their bins each week. When sent to landfill, it can have environmental and human health impacts, including contaminating waterways and increasing greenhouse gas emissions.

Reducing the amount of organic waste that households send to landfill can minimise the impact on public health, preserve ecosystems, and promote a more sustainable economy. This requires effective strategies and a coordinated approach from state and local governments, industry, and the community.

Tabled 28 August 2025.

Report summary

This report examines how effective the Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation’s and 3 selected South East Queensland councils’ strategies have been in reducing the amount of household organic waste sent to landfill.

What is important to know about this audit? |

- Household organic waste sent to landfill can release methane, a harmful greenhouse gas.

- Reducing the amount sent to landfill requires effective strategies and a coordinated approach from state and local governments, industry, and the community.

- The Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation (the department) is responsible for designing and overseeing Queensland’s waste reduction strategies. The Queensland Government has set targets for reducing the amount of organic waste sent to landfill.

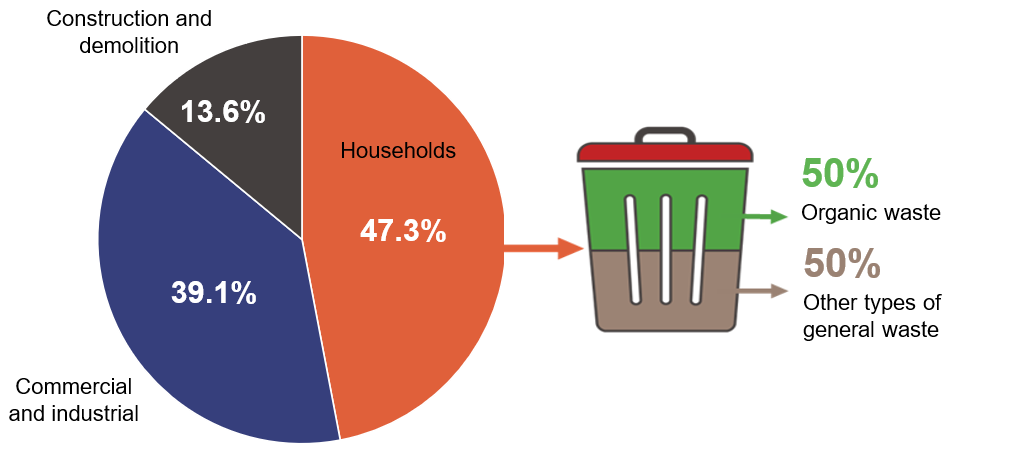

| The department reports that food and garden organic waste makes up about 50% of what households throw away in their rubbish bins each week. |

The Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation.

What did we find? |

The organics strategy has effective elements, but issues with data and measuring performance limit its effectiveness

- The Queensland Organics Strategy 2022–2032 (organics strategy) aligns to the state’s overarching Waste Management and Resource Recovery Strategy (waste strategy) introduced in 2019. It sets a clear vision for managing organic waste in Queensland, has clearly defined objectives, and is based on better practice waste management principles. The department designed the organics strategy after extensive consultation with key stakeholders.

- While the organics strategy has effective elements, there are some design issues that limit its effectiveness. The department set organic waste objectives and targets it cannot measure and therefore, it cannot determine if it is achieving those objectives. The department does not collect reliable data to identify the amount of organic waste households are sending to landfill. The department relies on measuring progress against broader household waste targets from the waste strategy, for which it does have data, but it is difficult to attribute reductions to organic waste actions.

- Additionally, the supporting action plan, Queensland Organics Action Plan 2022–2032 (action plan), does not clearly attribute state government departments’ responsibilities for actions or specify targets for all performance measures.

- We audited 3 large South East Queensland councils. All 3 have developed waste management plans that align to the organics strategy.

Queensland is not on track to achieve interim household waste targets

- Queensland is now a third of the way through its 10-year organics strategy and is not on track to achieve the interim household waste targets.

- The department has reported that the amount of household waste diverted from landfill has increased from 27 per cent in 2022–23 to 28 per cent in 2023–24. It remains well below the interim target, which aims to divert 55 per cent of household waste from landfill by 2025.

The department and the 3 councils have taken action to reduce the amount of organic waste sent to landfill

- Between 2021–22 and 2023–24, councils collectively increased the number of green lid bins for household garden organic waste across the state by 55 per cent.

- Queensland has rolled out approximately half a million green lid bins for households across the state.

- All 3 councils we audited were solely using their green lid bins to collect garden organic waste and not for food organic waste. They are recycling the garden organic waste and creating products, like mulch, and reducing the amount of waste sent to landfill. They are also trialling and implementing alternative solutions to kerbside collection, like food waste education and home composting.

- The department and councils have delivered educational and other behavioural change programs but have only evaluated some programs to identify whether they have been effective in reducing food organic waste.

Barriers have delayed progress in implementing the organics strategy

- Changes in the requirements for composting have created uncertainty for industry. These changes included limits on per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in compost and new odour regulations for new or expanding facilities producing compost. This is likely to have slowed investment in infrastructure, such as composting facilities.

- The department identified regulatory barriers as a risk to achieving the objectives of the organics strategy at the time of its design. However, it did not adequately assess, mitigate, or manage changes to the risk.

- The department has recently adjusted its approach to managing PFAS in compost following a review of its PFAS limits. It will no longer impose limits on PFAS when issuing new approval conditions for composters or enforce limits on existing approvals. Instead, the department will work collaboratively with the compost industry to develop guidance and undertake further monitoring to manage PFAS risks. The department will need to closely monitor PFAS risks and ensure it balances any health and environmental risks against the need to promote industry growth.

The department and the 3 councils are regularly tracking their progress but there are weaknesses in reporting

- The department tracks implementation progress of the action plan and provides quarterly summaries to its executive leadership team. Its existing reporting does not accurately reflect progress against the objectives of the organics strategy or key risks.

- In December 2024, the department reported that 24 out of 29 actions were progressing as planned. This overstates progress. We found that 9 actions reported as being on track were either behind schedule or at risk because they were related to other actions that were delayed.

- All 3 councils are monitoring and reviewing their plans and organic waste programs. This includes monitoring contamination rates in household green lid bins to measure the amount of non-organic waste. The 3 councils use this information to identify households that require further education.

What do entities need to do? |

We have made 5 recommendations to the Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation that focus on:

- assessing whether the objectives, goals, and targets in the organics strategy remain achievable

- providing clarity about how it intends to manage the risk of PFAS in compost

- strengthening its risk management practices

- improving access to funding for organic waste initiatives and infrastructure

- enhancing how it monitors, evaluates, and reports performance against the organics strategy.

1. Audit conclusions

The Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation’s (the department’s) and councils’ strategies to reduce the amount of organic household waste sent to landfill have not been effective to date. The department does not have data that captures the amount of organic waste sent to landfill and relies on household waste data and other information. With Queensland households diverting only 28 per cent of their waste from landfill in 2023–24, the department will not achieve its target of diverting 55 per cent of household waste by 2025.

The Queensland Organics Strategy 2022–2032 (organics strategy) has effective elements, including clearly defined objectives and alignment with other state and national waste plans, but design issues limit its overall effectiveness. The organics strategy has objectives that the department currently cannot measure progress against. As such, the department cannot determine the effect the organics strategy is having on reducing organic waste sent to landfill.

The department and the 3 councils have acted to reduce the amount of organic waste sent to landfill. This includes increasing the number of households across Queensland that have a green waste bin for garden organic waste and delivering education programs. The department does not yet know what impact these actions have had on achieving the objectives of the organics strategy. Inadequate risk management practices, data collection limitations, and changes to composting requirements have hindered progress.

Queensland is a third of the way through its 10-year organics strategy and now is an opportune time for the department to assess progress and decide if it should adjust its approach. It needs to communicate any change in approach clearly to ensure industry and local government are aligned on the key priorities for the future. The department’s existing governance committees are well placed to keep key stakeholders, such as councils and peak bodies, informed of progress against the organics strategy and seek their input.

2. Recommendations

| Reviewing Queensland’s organics strategy and action plan | Entity responses |

We recommend that the Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation, in collaboration with councils and industry:

| Agree |

| Regulating the compost industry | |

We recommend that the Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation:

| Agree |

| Strengthening risk management practices | |

We recommend that the Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation:

| Agree |

| Improving access to funding | |

We recommend that the Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation, in collaboration with key stakeholders:

| Agree |

| Monitoring, evaluating, and reporting performance | |

We recommend that the Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation, in collaboration with councils:

| Agree |

Reference to comments

In accordance with s. 64 of the Auditor-General Act 2009, we provided a copy of this report to relevant entities. In reaching our conclusions, we considered their views and represented them to the extent we deemed relevant and warranted. Any formal responses from the entities are at Appendix A.

3. Organic waste in Queensland

What is organic waste?

Households contribute nearly half of the waste generated and sent to landfill in Queensland each year.

Organic waste refers to waste that comes from living organisms, such as plants or animals. There are many types, including food, garden, agricultural, and timber waste.

Figure 3A shows that organic waste makes up approximately half of the waste Queenslanders throw away in their bins each week.

Queensland Audit Office, using data from the Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation.

The impacts of organic waste

Organic waste can have environmental and human health impacts, including:

- producing odours and pollutants

- contaminating waterways

- contributing to greenhouse gas emissions.

Reducing the amount of organic waste sent to landfill can minimise the impact on public health, preserve ecosystems, and promote a more sustainable economy.

There are other benefits of reducing the amount of organic waste sent to landfill, including creating valuable products, like compost, and jobs in the organics recycling industry.

What is Queensland doing to reduce the amount of organic waste sent to landfill?

Queensland’s strategy for managing waste

The Queensland Government’s current vision is to transition to a zero-waste society, as outlined in the state’s Waste Management and Resource Recovery Strategy (waste strategy). It aims to avoid, reuse, and recycle as much waste as possible. The Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation (the department) has consulted on a new draft Queensland Waste Strategy 2025–2030 and plans to publish the new strategy later this year.

The Queensland Government has committed $2.1 billion between 2021 and 2031 to better manage waste and deliver the waste strategy’s vision and targets.

Improving how Queensland manages organic waste is a priority for the Queensland Government.

Queensland’s organics strategy and objectives

The Queensland Organics Strategy 2022–2032 (organics strategy) forms part of the state’s waste strategy. It sets the framework for managing organic waste in Queensland.

The department has developed a supporting action plan for the organics strategy. The Queensland Organics Action Plan 2022–2032 (action plan) sets out the key actions for state government, councils, and industry to deliver on the objectives in the organics strategy.

The organics strategy and action plan are not prescriptive and give councils flexibility to identify and implement solutions tailored to their local area. This includes collection services for food and garden organic waste. This is different from the approach taken by New South Wales and Victoria, as summarised in Appendix C.

The Waste Reduction and Recycling Act 2011

The Waste Reduction and Recycling Act 2011 (the Act) outlines the principles for managing waste in Queensland. It promotes a circular economy principle, where materials are continuously reused and recycled. This seeks to minimise the amount of waste created and reduce its impact on the environment and human health.

The Act promotes that state and local governments, businesses, industry, and the community share responsibility for managing waste. It also imposes a levy on waste sent to landfill.

Queensland’s waste disposal levy

In July 2019, Queensland introduced a waste levy to reduce the amount of waste sent to landfill. The levy applies to 39 of the 77 councils in Queensland. It does not apply to councils in western remote Queensland or in First Nations local government areas, which have fewer residents and produce less waste.

Unlike other states and territories, the Queensland Government currently offsets the cost of the waste levy to households by providing annual payments to councils. These payments offset councils’ waste levy liability for household waste disposed to landfill. Since 2023–24, annual payments have been decreasing and are expected to continue decreasing over the coming years, which will shift cost to those producing waste.

Roles and responsibilities

A range of stakeholders share responsibility for reducing organic household waste in South East Queensland.

Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation

The department has primary responsibility for waste policy and strategy, legislation and regulation, and statewide performance monitoring, evaluation, and reporting. The department has lead responsibility for implementing the organics strategy and action plan. The department is also responsible for the licensing and compliance of organics processing activities.

Department of State Development, Infrastructure and Planning

The Department of State Development, Infrastructure and Planning is responsible for providing project support and funding to facilitate private sector investment in waste facilities. It aims to create viable infrastructure for the use of organic waste.

Councils

Councils are responsible for developing and implementing local waste management plans and providing waste services to local communities. This includes funding, managing, and contracting for programs, services, and infrastructure to avoid, reduce, and recycle organic waste in their areas.

Waste and recycling industry

Industry stakeholders are responsible for providing services to home owners, businesses, and local governments. They include private landfill operators, organics processors, and waste bin collection contractors.

Households

Since households are responsible for generating household waste, they play a vital role in sorting it properly and adopting sustainable practices to reduce the amount sent to landfill.

Other stakeholders

Businesses, government entities, and other industries can implement waste reduction and recycling programs and reduce their environmental impact. Other stakeholders, such as peak bodies and council advocacy bodies, work with government on key priorities, such as policy, to improve outcomes.

What did we audit?

This audit assessed how effective the Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation’s and selected South East Queensland councils’ strategies are in reducing organic household waste sent to landfill.

We audited:

- the Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation

- Brisbane City Council

- Council of the City of Gold Coast

- Sunshine Coast Council.

We focused on councils in South East Queensland because they account for 70 per cent of household waste sent to landfill in Queensland. These councils have already trialled or implemented organic waste programs and services.

We engaged the Department of State Development, Infrastructure and Planning as a stakeholder, given its role in providing project support and funding to facilitate private sector investment in waste facilities – but did not include it as an auditee given its limited role.

4. Progress in reducing organic household waste sent to landfill

In this chapter, we report on the Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation’s (the department’s) and 3 selected South East Queensland councils’ progress in implementing organic household waste strategies and their effectiveness.

Is the organics strategy well designed?

The organics strategy has strong elements, but some design issues limit its effectiveness

The 10-year Queensland Organics Strategy 2022–2032 (organics strategy) has clearly defined objectives. These objectives reflect the Queensland Government’s broader priorities for reducing the amount of waste that households send to landfill.

The department undertook extensive consultation when designing the organics strategy. It consulted a broad range of stakeholders, including councils, industry, and peak bodies. We spoke with a range of stakeholders who said the department had consulted effectively during the design. This approach enabled it to better understand opportunities and challenges across sectors, and tailor solutions.

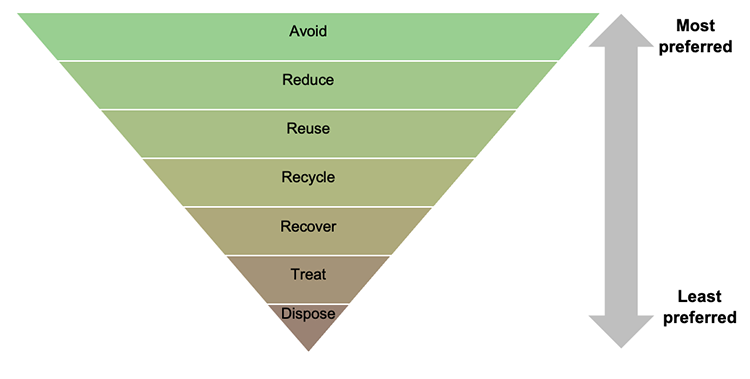

The organics strategy incorporates better practice waste principles

The organics strategy incorporates better practice waste principles, including the waste and resource management hierarchy. Other jurisdictions apply the hierarchy as a better practice approach for managing waste. The preferred approach in the hierarchy is to avoid generating the waste in the first instance, followed by options to reduce, reuse, and recycle waste as shown in Figure 4A.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office from the Waste Reduction and Recycling Act 2011.

Design issues in the organics strategy and action plan

While the organics strategy and the Queensland Organics Action Plan 2022–2032 (action plan) have effective elements, there are design issues that limit their effectiveness. The organics strategy includes objectives that the department cannot measure progress against. As such, the department cannot determine if the organics strategy is working or whether it needs to adjust its approach. The department needs to address this gap if it is to accurately evaluate the organics strategy in late 2025.

There is also opportunity to improve the action plan supporting the organics strategy. The existing action plan does not clearly define which state government departments are responsible for specific actions. While we did not find evidence that indicated this has impeded progress, it has the potential to result in duplication and delays. In addition to this, the department only specified time frames for the performance measures of some actions, and not all.

Local and regional plans align with the organics strategy

All 3 councils we audited have developed waste management plans. Their plans, which are required under the Waste Reduction and Recycling Act 2011, also include the principles of the waste and resource management hierarchy. They align with the South East Queensland Waste Management Plan (regional plan) and the organics strategy. The regional plan aims to improve waste management across South East Queensland and ensure councils are working together in a coordinated approach.

Is the organics strategy working?

The organics strategy sets 3 objectives that the state is aiming to achieve by 2030:

- halving the amount of food waste generated

- diverting from landfill 80 per cent of the organic material generated

- achieving a minimum organics recycling rate of 70 per cent.

The department captures some waste data but lacks the reliable data it requires to assess against the 3 objectives. It does not capture the total amount of organic waste generated and sent to landfill across Queensland. The department relies on general household waste data, information, and targets to assess progress against the organics strategy. The household waste targets are from the state’s overarching Waste Management and Resource Recovery Strategy (waste strategy). Household waste data and targets may offer some insight into how the state is tracking against the objectives of the organics strategy. Research has indicated that organic waste makes up around half of what Australian households throw away each week.

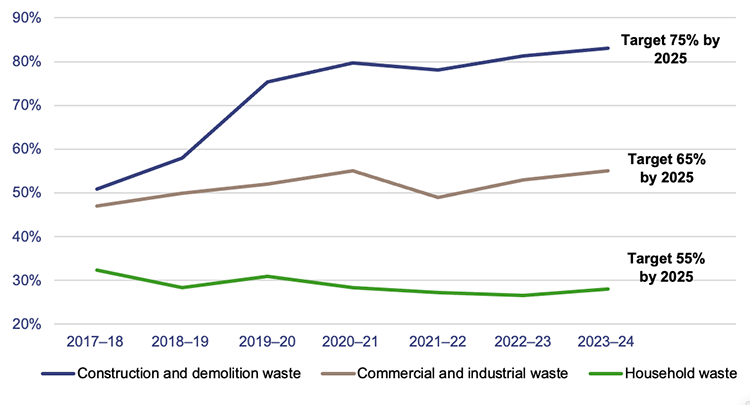

Queensland is not on track to achieve interim household waste targets

Queensland is now a third of the way through its 10-year organics strategy and is not on track to achieve the interim targets for reducing, diverting, and recycling household waste.

Figure 4B shows progress against the household waste targets.

| Targets | 2017–18 baseline data | 2023–24 performance results | 2025 interim targets | 2030 long-term targets | Progress as reported by the department |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reduction in household waste generation per capita | 540kg | 7% | 10% | 15% | Unlikely to reach interim target |

| Landfill diversion rate for household waste | 32.4% | 28% | 55% | 70% | Unlikely to reach interim target |

| Recycling rate for household waste | 31.1% | 28% | 50% | 60% | Unlikely to reach interim target |

Queensland Audit Office, using data published by the Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation in its annual reports.

Diverting household waste from landfill

The department reports that the amount of household waste diverted from landfill has increased from 27 per cent in 2022–23 to 28 per cent in 2023–24. It remains well below the interim target, which aims to divert 55 per cent of household waste from landfill by 2025.

The department reports that other waste streams, including commercial and industrial, have increased the amount of waste diverted from landfill. The construction and demolition waste stream has achieved its interim target, and the commercial and industrial stream is progressing towards its interim target but is uncertain if it will achieve it.

Figure 4C shows the percentage of waste that Queensland diverted from landfill between 2018 and 2024 by waste stream.

Queensland Audit Office, using data published by the Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation in its annual reports.

Recommendation 1 We recommend that the Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation, in collaboration with councils and industry, assesses whether the objectives, goals, and targets in the Queensland Organics Strategy 2022–2032 are achievable, and uses this information to inform its approach going forward. This should include assessing the value and priority of actions based on progress to date, known risks, and relevant performance information. |

Several challenges have delayed progress

A variety of challenges have affected the progress of the organics strategy, including changes in composting regulatory requirements, local councils’ access to grant funding, and a lack of infrastructure.

Changes to the regulatory requirements for compost

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are synthetic substances that are often called ‘forever chemicals’, as they can take years to break down in the environment. PFAS can contaminate various types of waste, including organic waste used to produce compost.

To manage the human health and environmental risks associated with PFAS, the department developed PFAS limits for compost.

The department also introduced new regulatory requirements to manage odour from compost activities.

It did this at the same time it was designing and starting to implement the organics strategy and action plan. These changes are summarised in Figure 4D.

The department released updated model operating conditions to help composters manage PFAS risks in their compost. The conditions, which included limits on PFAS, were not mandatory.

Over this period, the department updated licenses for some composters to include PFAS limits depending on the environmental risks of their site. The department did not automatically impose the limits on all composters.

The department released a regulatory position statement to provide greater clarity on how it would manage PFAS contamination in organic waste and compost.

The department implemented odour regulations on new or expanding facilities located within 4 kilometres of a residential zone that receive odorous waste to use in-vessel composting or enclosed processing. This was to reduce odour on nearby residents.

The Queensland Government commissioned a review of the PFAS limits for compost. It concluded that its approach was scientifically sound but the limits were ‘conservative’, meaning the department set a restrictive limit.

As a result of the review, the department decided it will no longer impose limits on PFAS when issuing new approval conditions for composters or enforce limits on existing approvals. Instead, it is working with the compost industry to develop guidance and undertake further monitoring to manage PFAS risks in organic waste.

Notes: Enclosed processing occurs in a large building or section of a building, and in-vessel composting involves processing organic waste in a closed container.

Queensland Audit Office using information provided by the Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation.

The department updated the licenses for 24 out of 97 composters between August 2021–July 2024 to reflect these regulatory changes. The changes created uncertainty across industry. Many of the stakeholders we spoke to acknowledged the need to manage PFAS risk in compost but shared a consistent view that the limits were too restrictive.

Balancing the health and environmental risks of PFAS in compost with the broader risks of failing to reduce organic waste in landfill is a challenge. The department identified policy and regulatory frameworks as a risk to achieving the objectives of the organics strategy at the time of its design. But it did not adequately assess, mitigate, or manage the risk. The department is considering how it can address the sources of PFAS in waste, like food packaging, to manage this risk going forward.

In addition to the changes in PFAS limits, the department made regulation changes for compost facilities to reduce the impacts of odour on nearby residents in July 2024. These changes provided the department with the power to impose a requirement on new or expanding composting facilities located within 4 kilometres of a residential zone that receives odorous waste to use in-vessel composting or enclosed processing. These changes are likely to have increased processing costs for councils and required more expensive infrastructure.

Recommendation 2 We recommend that the Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation provides clarity about how it intends to manage the risk of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in compost. This should include:

Recommendation 3 We recommend that the Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation strengthens its risk management practices. This should include:

|

Limitations for councils accessing grant funding

In August 2023, the Queensland Government committed $151 million to help eligible councils implement services to collect and transport household organic waste. Since August 2023, the department has granted funding to 6 councils. At the time of our audit, the department had allocated 27 per cent ($41 million) of the $151 million, despite being halfway through the funding application period.

Councils have experienced challenges and delays accessing grant funding. One council waited approximately 22 months and another council waited 16 months to receive grant funding after they first submitted their applications. The department reported that in some cases these delays were the result of it seeking additional evidence. Councils advised us that they would benefit from a more simplified and timely grant funding application process and more standardised contracts.

Councils can only use the grant funding to implement organic waste collection services and other related activities, like behaviour change initiatives. This restricts them to funding waste collection services and inhibits them from using it for smaller initiatives, such as encouraging home composting.

They can choose to collect garden organic waste initially and transition to food organic waste later, or they can do both. To date, councils in Queensland have chosen to roll out green lid bin services for garden organic waste only. Some have been reluctant to use their green lid bins to collect food organic waste due to various factors, including costs, lack of community support, and uncertainty stemming from changes to composting regulations.

Lack of infrastructure

The organics strategy highlights the importance of infrastructure to divert more organic waste from landfill. Infrastructure is necessary to process organic waste and convert it into valuable products, like compost. The changes to control odour led to industry reluctance to invest in new compost processing facilities, primarily due to the increased cost to build compliant facilities. This has also affected the users of recycled organic products.

In December 2022, the department funded the Council of Mayors South East Queensland to develop a roadmap and implementation plan to help identify infrastructure needs and inform funding decisions for South East Queensland. The roadmap was finalised in 2024. However, detailed project planning now needs to be finalised to inform any associated funding decisions. This includes $54 million allocated to organics processing infrastructure, through the South East Queensland City Deal.

Recommendation 4 We recommend that the Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation, in collaboration with key stakeholders, improves access to funding for infrastructure and organic waste initiatives. This should include:

|

What actions are the department and councils taking?

The department and the 3 councils have implemented a range of programs and services to reduce the amount of household organic waste sent to landfill. The following section highlights some of the initiatives they have taken.

Increasing green lid bin services for residents

The department reports that the number of green lid bins for households has increased across Queensland. Most residents across the state have a red lid bin for general waste and a yellow lid bin for recycled waste. Councils providing a green lid bin service collect household garden organic waste and can recycle this through mulching or composting. This reduces the amount of garden organic waste that residents send to landfill through their red lid bins.

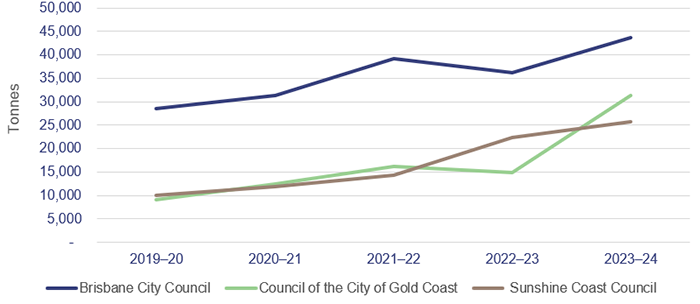

Queensland has rolled out approximately half a million green lid bins for households across the state.

As shown in Figure 4E, the number of green lid bins across Queensland has increased by 55 per cent from 2021–22 to 2023–24. In 2023–24, approximately 20 per cent of households in Queensland had a green lid bin.

Queensland Audit Office, using data provided by the Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation.

All 3 councils we audited are providing green lid bin services to households. Residents pay for the service through their rates. The Sunshine Coast Council made it mandatory for households to use a green lid bin in July 2022, and the Council of the City of Gold Coast made it mandatory in July 2023. Brisbane City Council changed its green lid bin service from opt-in to opt-out from 1 July 2025, with the ability for free-standing households to opt-out. The 3 councils have increased their green lid bins by 73 per cent, from 211,180 in 2021–22 to 366,198 in 2023–24.

Figure 4F shows the amount of garden organic waste the 3 councils diverted from landfill through green lid bin services between 2019–20 and 2023–24.

Queensland Audit Office, using data provided by the Brisbane City Council, Council of the City of Gold Coast, and Sunshine Coast Council.

Planning for the rollout of a green lid bin service

Councils considering rolling out a green lid bin service need to understand whether it is viable for their local government area. This includes understanding the ongoing costs of providing the service, such as:

- labour, fuel, and vehicle costs to collect and transport garden organic waste

- costs to process garden organic and/or food organic waste

- programs and materials to educate residents about what they can put in their green lid bins. The success of green lid bins is contingent upon residents getting this right.

They also need to consider the impact on rate payers and factor in potential cost increases, like rising landfill costs, after the go-live date. Deciding whether they will make the service mandatory or optional for residents will be necessary as it will impact on the costs of providing the service. It will also dictate the extent of the education they need to provide to residents.

Initiatives to reduce food organic waste

The Sunshine Coast Council plans to use its green lid bin service to also collect food organics. It is seeking tenders to build a new facility to process food organic waste. The changes to the regulations for compost have delayed its progress.

The Brisbane City Council and the Council of the City of Gold Coast are trialling, or have implemented, different initiatives to reduce food organic waste sent to landfill. They include providing:

- food organic bins for multi-unit dwellings

- community composting hubs

- home composting rebate programs.

These initiatives are relatively early in their implementation. While initial results indicate some success, it is too early to accurately assess their effectiveness.

Case study 1 (Figure 4G) highlights the early results for Brisbane City Council’s home compost rebate program.

| Home compost rebate program |

|---|

The Brisbane City Council’s compost rebate program offers residents a rebate for the composting and food waste recycling equipment they purchase. This includes compost bins, worm farms, and in-sink food disposal systems. Between 1 July 2020 and 30 June 2025, Brisbane City Council received 21,108 claims for home compost rebates. The council undertook a survey of 3,524 residents in early 2025 to evaluate the effectiveness of the rebate program and to understand what impact it has had on changing the behaviour of residents. The survey found that:

The council estimates that the rebate program is currently diverting 150 tonnes of food organic waste from landfill each week. |

Queensland Audit Office using information provided by the Brisbane City Council.

Delivering educational and other behavioural change programs

The department and the 3 councils have designed and launched a range of education materials and programs to reduce the food and garden organic waste that households send to landfill. These focus on increasing awareness and changing behaviour to help avoid waste, improve recycling, and reduce contamination. Contamination occurs when residents put the wrong type of waste in the incorrect-coloured bin. For example, non-organic waste, such as plastic and food packaging, in their green lid bins.

Educating households about how they can reduce their food waste

The department has rolled out the ‘Love Food Hate Waste’ challenge, which is an evidence-based program that focuses on reducing food waste in households. It aims to achieve this through actions such as:

- using leftovers and freezing excess food more effectively

- preparing only what is needed and using a shopping list more often.

The Council of the City of Gold Coast is currently promoting the campaign on its website. The Sunshine Coast Council promoted the campaign on its website and social media, and ran a series of library workshops. The Brisbane City Council previously used the Love Food Hate Waste campaign but is now using its own food waste education material on its website.

Helping households put their waste in the correct bin

The department has developed education materials and toolkits to help councils that are expanding and rolling out new green lid bin services. This includes the ‘Let’s get it sorted’ partnership program and campaign, which provides funding and materials to councils to help residents understand what they can and cannot put in their green bins to reduce contamination. This helps provide consistent information across the state about how to maximise recycling, reduce contamination in bins, and use the Recycle Mate app to access local recycling information.

Additionally, all 3 councils are raising awareness through other means. This includes shopping centre displays, frequently asked questions on their websites, and providing fridge magnets to residents to educate them on the correct use of the green lid bin.

Measuring the effectiveness of education programs

It can be challenging to measure the effectiveness of education programs as many factors can contribute to changes in behaviour. The department set a goal to have 50 per cent of the Queensland population aware of messages to avoid food waste by 30 June 2023. It has not assessed whether it has achieved this target or whether existing campaigns have helped to reduce the amount of food waste sent to landfill.

How are entities improving their approaches?

The department needs to improve its reporting

The department is tracking progress against the action plan but it is not assessing performance and reporting this information effectively. It regularly monitors the overall status of actions and reports this information to its executive leadership team through a dashboard each quarter. But it does not report progress against the objectives and targets of the organics strategy and action plan or adequately brief up about key risks and delays. The department developed performance measures for all 29 actions in the action plan, but did not track performance against the metrics. In some cases, this is due to a lack of reliable data.

At the time we undertook the audit, the department reported that the action plan was 83 per cent on track, stating that 24 out of the 29 actions were progressing as planned. This overstates its progress. In addition to the 5 actions experiencing delays, we found that another 2 actions reported as on track were in fact behind schedule.

Additionally, the department’s reporting did not highlight that 7 actions were at risk of not meeting time frames due to delays with one of the interconnected actions.

The department engages with key stakeholder groups responsible for implementing the organics action plan but does not provide them with performance information. Without this information, stakeholders cannot understand progress against the objectives of the organics strategy and focus their effort on the areas that matter most.

Recommendation 5 We recommend that the Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation, in collaboration with councils, improves how it monitors, evaluates, and reports performance against the Queensland Organics Strategy 2022–2032 and the Queensland Organics Action Plan 2022–2032. This should include:

|

The department plans to evaluate the effectiveness of the organics strategy

The department plans to evaluate, review, and update the organics strategy and action plan in late 2025. It has identified opportunities for improvement leading into the review, including reducing the number of actions and steps, realigning funding to priorities, and resolving barriers to implementation. As part of this review, the department will consider the new draft Queensland Waste Strategy 2025–2030, which it plans to publish in late 2025.

Councils are using data to improve how they manage organic waste

All 3 councils are analysing data, including contamination rates, volumes of garden waste, and service costs, to improve how they manage organic waste. They collect data through various means, including driver observations at the point of collecting waste and weighing contamination removed after collection. They also undertake bin audits.

All 3 councils we audited have undertaken bin audits to examine the contents of household bins. This helps them to understand trends in the amount of organic waste sent to landfill through red lid bins and assess the effectiveness of behavioural change initiatives.

The bin audit data for the 3 councils showed a reduction in the amount of garden organic waste sent to landfill in red lid bins between 2020 and 2024. This data is summarised in Appendix D. We could not compare bin audit data across the 3 councils due to differences in the approach, timing, and how often councils undertake the audits.

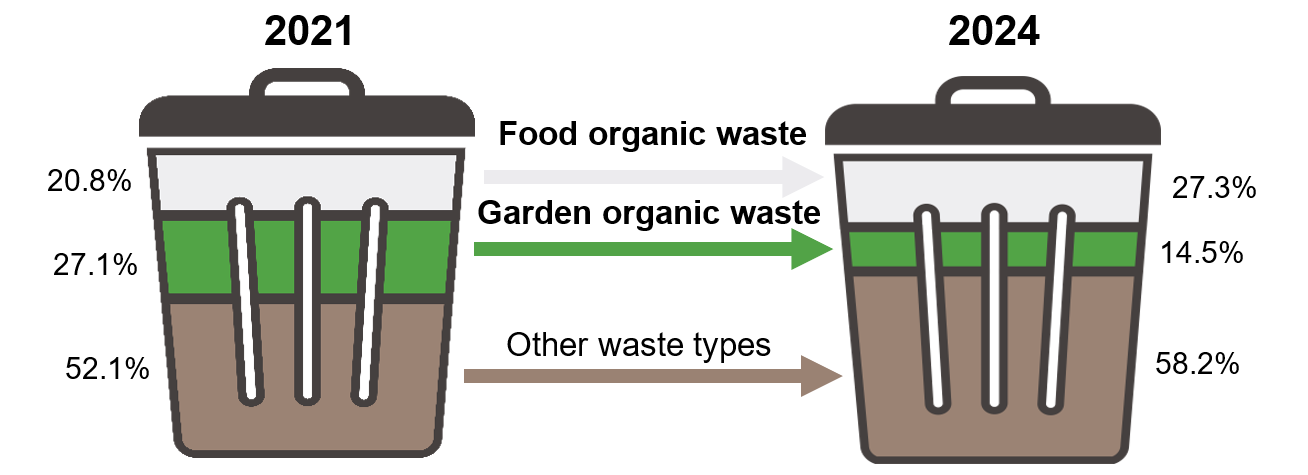

Figure 4H shows the results of the Council of the City of Gold Coast’s 2021 bin audit and its most recent bin audit in 2024.

Queensland Audit Office, using bin audit reports from the Council of the City of Gold Coast.

It shows that the amount of garden organic waste in households’ red lid bins has reduced from 27.1 per cent in 2021 to 14.5 per cent in 2024. The Council of the City of Gold Coast made it optional for households to have a green lid bin in 2013 and mandatory in July 2023.

The department is working to establish a standard that councils can adopt when undertaking bin audits. Regular and consistent bin audit data will help the department and councils to assess how effective initiatives have been in reducing contamination and organic waste sent to landfill in Queensland.

All 3 councils are using the bin audit data and other data sources to improve how they manage organic waste. This includes:

- educating households in how to treat their waste and reduce contamination

- identifying if they require extra labour and machinery to remove contamination from garden waste

- assessing whether the number of contracts with existing operators is adequate to process the volumes of garden organic waste.