Overview

Most public sector entities prepare annual financial statements and table these in parliament each year. Our report summarises their audit results, and evaluates the timeliness of their financial reporting and effectiveness of their internal controls.

Tabled 16 March 2023.

Report on a page

This report summarises the audit results of 253 Queensland state government entities, including the 20 core government departments. It also analyses the consolidated financial performance of the Queensland Government (referred to as the ‘total state sector') for 2021–22.

Financial statements are reliable

The financial statements of all departments, government owned corporations, most statutory bodies, and the entities they control are reliable and comply with relevant laws and standards. However, ongoing delays in the tabling of annual reports mean the financial statements of departments and statutory bodies are dated and less relevant by the time they are released to the public.

The state’s financial performance has improved due to market conditions

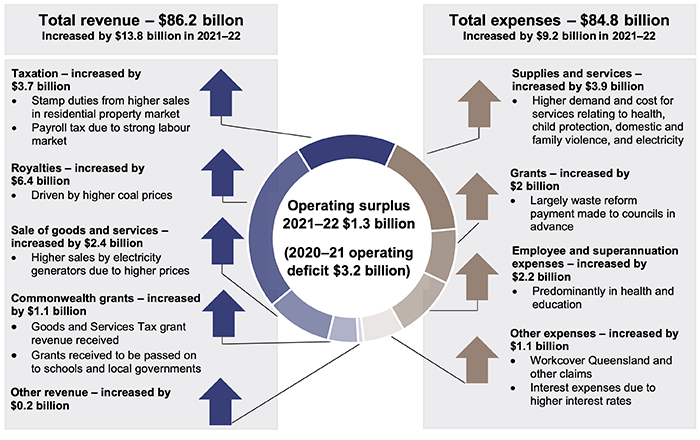

In 2021–22, the total state sector reported a net operating surplus of $1.3 billion (2020–21: a deficit of $3.2 billion). The improved financial performance of the state was due to market conditions that resulted in significant increases in revenue of $13.8 billion (19 per cent), including:

- royalty revenue (from the extraction of minerals), due to higher coal prices

- stamp duty, driven by a strong residential property market and an increase in the number of property sales at higher prices

- payroll tax, due to growth in employment and wages.

Demand for public services is growing, particularly in the areas of health, education, child protection, and domestic and family violence. The cost to deliver these services is also increasing. Overall, total state sector expenses increased by $9.2 billion (12.2 per cent) in 2021–22.

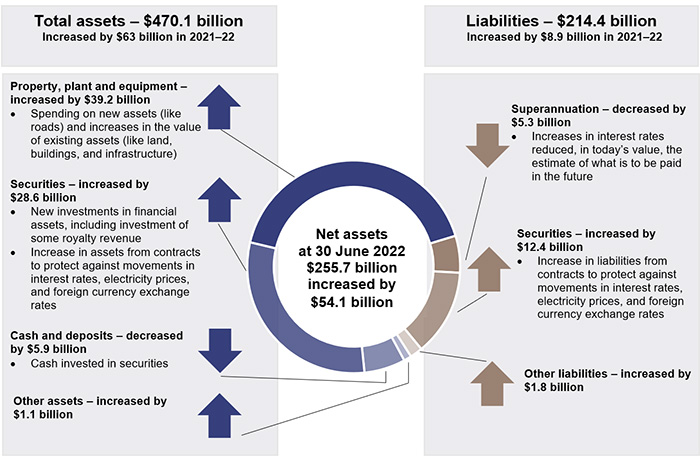

The state reported an increase of $54.1 billion (27 per cent) in its net assets in 2021–22. This was largely driven by spending on new assets (like roads) and increases in the value of existing assets (like land). Investments also increased, with some of the higher-than-expected royalty revenues being invested in long-term assets.

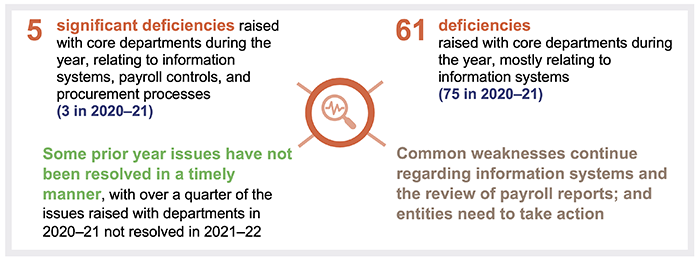

Entities continue to have common weaknesses and are not resolving them in a timely manner

The internal controls (people, systems, and processes) entities have in place are generally effective, but the same common weaknesses continue. These include entities not:

- securing their information systems

- reviewing payroll reports and consistently approving employee transactions

- monitoring their procurement and contract management processes.

Some of these weaknesses require immediate action by management.

Over a quarter of deficiencies raised with departments in 2020–21 were not resolved in accordance with agreed time frames. This exposes the departments to a higher risk of operational failures, non‑compliance, fraud, or error. Independent audit committees can play a critical role in holding management to account and overseeing the implementation of audit recommendations.

Recommendations for entities

Audit committees to actively monitor the implementation of audit recommendations (including internal audit recommendations) and encourage the timely resolution of outstanding internal control weaknesses (audit committees of all entities) |

|

| REC 1 |

We recommend that audit committees of public sector entities actively monitor the implementation of audit recommendations and encourage the timely resolution of outstanding internal control weaknesses. This should ensure the agreed recommendations address the underlying cause of the issue and issues are resolved in accordance with agreed timelines. Audit committees play an integral role in ensuring effective internal controls, including holding management to account so that identified weaknesses are resolved appropriately and in a timely manner. |

Prior year recommendations need further action

Entities have taken some corrective action to address the recommendations we made in our report last year. Despite this, we continue to identify weaknesses that require further action with regard to procurement, payroll processes, and the security of information systems.

The number of annual reports entities have tabled before the legislative deadline has improved this year, and the tabling of annual reports started the earliest it has in 4 years. But most annual reports were still consistently not tabled until the week before the legislative deadline. This practice unnecessarily delays audited financial information being shared with the community. This is inconsistent with Professor Coaldrake’s 2022 Review of culture and accountability in the Queensland public sector, which emphasised the need for 'a commitment to openness, supported by accountability’. Our recommendation to consider opportunities to improve timeliness remains outstanding.

We have included a full list of prior year recommendations and their status in Appendix C.

Reference to comments

In accordance with s.64 of the Auditor-General Act 2009, we provided a copy of this report to relevant entities. In reaching our conclusions, we considered their views and represented them to the extent we deemed relevant and warranted. Any formal responses from the entities are at Appendix A.

1. Entities in this report

Notes: *These do not include entities exempted from audit by the Auditor-General (see Appendix F) or entities not preparing financial reports (see Appendix G). **These are entities controlled by one or more public sector entities.

Queensland Audit Office.

Core departments

It also includes our assessment of the 20 core departments’ controls over financial systems and processes, identifying learnings for all state government entities. In 2021–22, core departments were entities gazetted as departments under the Public Service Act 2008, and were responsible for most public services provided by departments.

The other 7 departments have been established under the Financial Accountability Act 2009, for example, the Electoral Commission of Queensland, Legislative Assembly and Parliamentary Service, Office of the Governor, and Public Service Commission.

Queensland Audit Office.

Our assessment of the financial reporting and internal controls of other Queensland state government entities are included in the relevant sector reports on our website at www.qao.qld.gov.au/reports-resources/reports-parliament, including energy and health.

Providing services across Queensland

The departments in Figure 1B provide services across the state. The Queensland Audit Office’s dashboard, QAO Queensland, brings together important information about the finances and services of Queensland state and local government entities. It uses 3 common regional boundaries:

- local government areas

- statistical areas (used by the Australian Bureau of Statistics and by state entities to collect and report on information, including the state budget)

- hospital and health service areas.

This allows users to search by an address and identify the services and the financial results for their local area, including for councils, education, health, water, and electricity. The dashboard is available on our website at www.qao.qld.gov.au.

2. Financial performance of the Queensland Government

This chapter analyses the consolidated financial performance of the Queensland Government (referred to as the total state sector) for 2021–22.

The financial performance of the Queensland Government has improved

The Financial Accountability Act 2009 requires the Treasurer to prepare annual consolidated financial statements for the Queensland Government. The Auditor-General issued an unmodified audit opinion on the Queensland Government’s 2021–22 consolidated financial statements on 19 October 2022, which means the financial statements can be relied upon.

In 2021–22, the total state sector reported a net operating surplus of $1.3 billion (2020–21: $3.2 billion deficit). The improved financial performance of the state was mainly due to significant increases in stamp duty (from a strong residential property market) and royalty revenue (through an increase in coal prices). Figure 2A provides an overview of movements in the state’s financial results.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office from the 2021–22 Report on State Finances of the Queensland Government.

Queensland's revenue is sensitive to market conditions that the government cannot control. While positive market conditions continue, it is important that the government invests wisely and plans for future uncertainty in revenue. The Queensland Government’s 2022–23 Budget Update forecasts that royalty revenue is expected to increase again in 2022–23. The government plans to invest $3 billion of this to fund future infrastructure in regional Queensland. Our Forward Work Plan 2022–25 includes an audit topic on Financial forecasting by the state government that will examine how the framework for preparing the state budget supports the government’s identified fiscal principles and the objectives and measures identified in key economic plans.

In our upcoming report on Managing Queensland’s debt and investments, we will examine how the state is managing its debt and investments, including significant investments it has made, and the financial performance of these investments.

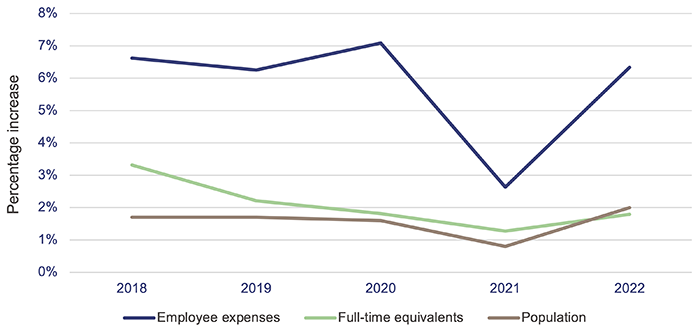

Employee expenses have increased by 6 per cent

Employee costs are the state’s largest single operating expense. In 2021–22, the state recorded expenses of $30.2 billion in relation to its employees, an increase of $1.8 billion (6.3 per cent) from the previous year. This increase mainly occurred in the health and education sectors.

In the past 5 years, there has been a steady increase in employee expenses (32.4 per cent since 2016–17, an average of 5.8 per cent each year), due to increases in full-time equivalent employees (10.8 per cent over 5 years, mostly in frontline employees), in addition to increases in pay rates from enterprise bargaining arrangements. Employee expenses are forecast to increase further in future years due to the enterprise bargaining agreements that have been negotiated. Agreements for nurses, midwives, and teachers provide for a pay increase of 4 per cent in 2022–23, 4 per cent in 2023–24, and 3 per cent in 2024–25, and a potential cost-of-living adjustment depending on the level of inflation.

Figure 2B shows the percentage increase in total state sector employee expenses, the number of full‑time equivalent employees, and Queensland’s population growth over the past 5 years. The rate of growth slowed in 2020 and 2021. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, full-time equivalent staffing caps were imposed on departments, and salary increases associated with some enterprise bargaining arrangements were deferred to 2021–22.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office from the Report on State Finances of the Queensland Government 2017–18 to 2021–22, and data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics – National, state and territory population – Estimated resident population.

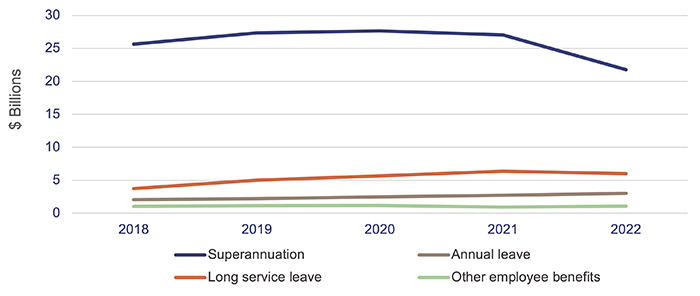

Almost 15 per cent of the state’s total liabilities relate to employees. They include superannuation obligations and other employee benefits such as long service leave and recreation leave.

As of 30 June 2022, the Queensland Government’s superannuation liability was $21.8 billion, a significant decrease of $5.3 billion from the prior year.

The value of this liability is calculated by the State Actuary applying the requirements of the Australian Accounting Standards Board’s (AASB) accounting standard AASB 119 Employee Benefits. The underlying model used to value the liability is complex and involves expert judgement and estimation in selecting long-term assumptions, including salary growth, interest rates, and inflation. The valuation is highly sensitive to changes in these assumptions.

This year, the interest rate (which is used to estimate future payments in today’s dollars) applied was 3.7 per cent. This was a significant increase on the rate of 1.5 per cent applied in 2020–21 and was the main reason for the reduction in the superannuation liability.

Figure 2C shows the movement in the state’s employee benefit obligations over the past 5 years.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office from the Report on State Finances of the Queensland Government 2017–18 to 2021–22.

While the state’s superannuation liability continues to fluctuate from year to year, the state’s obligations with respect to recreation leave and long service leave have generally risen since 2018, consistent with the increase in employee numbers and salary rates.

An increase in cash received allowed for more spending

The consolidated fund is the Queensland Government’s central bank account. Each year, government departments receive funding from the consolidated fund through appropriations. The amounts appropriated to departments are approved by parliament as part of the annual state budget process.

The Financial Accountability Act 2009 requires the Treasurer to keep a ledger recording the amounts received into and paid out of the consolidated fund. The Consolidated Fund Financial Report acquits these amounts each year. It also compares amounts provided to departments against the amounts approved by parliament.

Section 35 of the Financial Accountability Act 2009 refers to ‘unforeseen expenditure’, which is expenditure made in advance of the annual appropriation. This occurs because additional expenditure arises for departments that was not originally budgeted for.

There was an increase in unforeseen expenditure of $2.4 billion in 2021–22, with the total of unforeseen expenditure being over $2.8 billion. The improved financial performance of the state, and in particular the significant increase in revenue, allowed some of this expenditure to be brought forward to 2021–22.

Unforeseen expenditure in 2021–22 was mainly attributed to the following departments:

- Environment and Science ($623 million) – funding for advance payments to councils in relation to the waste disposal levy described in Case study 1 in Figure 2D

| Advance payments made for waste disposal levy |

|---|

|

As part of the state’s overall waste management strategy, the government introduced a waste disposal levy, which began on 1 July 2019. Landfill operators (local councils and private businesses) pay a levy to the Queensland Government based on the weight of levy-able waste disposed of to landfill. DEFINITION To mitigate the direct impact of the waste levy on households, annual payments are made to eligible local councils. The annual payment offsets the councils’ levy liability for the municipal solid waste they dispose of in landfill. Queensland is the only state government that provides this payment. In June 2022, the Department of Environment and Science made a lump sum payment of $672.4 million to 43 councils, with individual amounts prescribed by the Waste Reduction and Recycling Regulation 2011. This payment reflected the next 4 financial years’ (2022–23 to 2025–26) annual payments at the time, and was possible because of increased revenue recognised by the state in 2021–22. To help Queensland meet its waste targets and those set by many councils themselves, significant and critical investment decisions need to be made by both the state and local governments in the coming years. Receiving these payments earlier as a lump sum provides councils with certainty for budget planning. It also enables greater flexibility when they are making investment decisions to help reduce waste generation and increase resource recovery. Early adopters of waste diversion can redirect any potential advance payment savings into other resource recovery initiatives for the benefit of their communities. Over time, the payments to councils are expected to decrease as Queensland moves closer to its waste and resource recovery targets. Annual payments to councils will be reviewed again in 2025. Our Forward Work Plan 2022–25 includes an audit topic on Managing waste that will assess the effectiveness of state government strategies. This will include their effectiveness in assisting councils to manage waste to achieve the 2050 waste targets. |

Prepared by the Queensland Audit Office from information provided by the Department of Environment and Science.

- State Development, Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning ($574 million) – funding for the prepayment of 2022–23 financial assistance grants to local councils, recovery and reconstruction costs as a result of the extreme rainfall events in Queensland in January and February 2022, and the Queensland Regional Accommodation Centre.

We received a request from an elected member to perform an audit over the Queensland Regional Accommodation Centre (Wellcamp). We are currently identifying the various costs, understanding the procurement process, and reviewing leases and other agreements including the use of confidentiality provisions. We will report separately to parliament on this audit

- Queensland Treasury ($552 million) – additional funding to acquire the proposed site for the international broadcasting centre for the Brisbane 2032 Olympic and Paralympic Games. Additional funding was also provided for the HomeBuilder grant program (with funding received from the Australian Government and passed through to eligible home owners)

- Transport and Main Roads ($330 million) – additional funding for the accelerated delivery of various capital programs, and to assist in offsetting COVID-19 impacts on fare revenue

- Queensland Fire and Emergency Services ($224 million) – additional funding for the COVID-19 response (primarily for quarantine accommodation), additional firefighters, and funding that was reallocated from the Public Safety Business Agency (which was abolished on 1 July 2021)

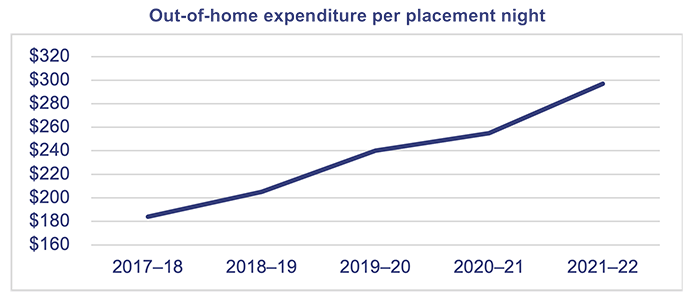

- Children, Youth Justice and Multicultural Affairs ($176 million) – additional funding primarily for out‑of‑home care (including foster care, kinship care, and residential care) and services. This was in response to ongoing demand pressures in the child protection system, as described in Case study 2 in Figure 2E.

| Out-of-home care costs for children are increasing |

|---|

|

Between 2017–18 and 2021–22, the Department of Children, Youth Justice and Multicultural Affairs saw a 28.6 per cent increase in the rate of children aged zero to 17 years entering out-of-home care (which includes foster care, kinship care, and residential care). This is significantly higher than the increase in Queensland’s population over this time. (The population of people aged zero to 19 years increased 5.7 per cent from 2016 to 2021.) While demand for child support services has increased, there has not been an equivalent increase in the availability of family-based placements like foster care or kinship care. The department has purchased additional services through residential placements to meet this demand, but this comes at a higher cost. Out-of-home care expenses have risen from $184 per placement night in 2017–18 to $297 in 2021–22 (an increase of 61 per cent). This has also been attributed to the increased number of children in care with complex needs and challenging behaviours, and the higher associated costs to provide appropriate placement and support for these children. The Queensland Government’s 2022–23 budget includes increased funding of $2.2 billion over 5 years for out‑of‑home care services to keep children safe and respond to an increase in demand in the child protection system. |

Prepared by the Queensland Audit Office from information provided by the Department of Children, Youth Justice and Multicultural Affairs; and Australian Bureau of Statistics Queensland Census Data 2016 and 2021.

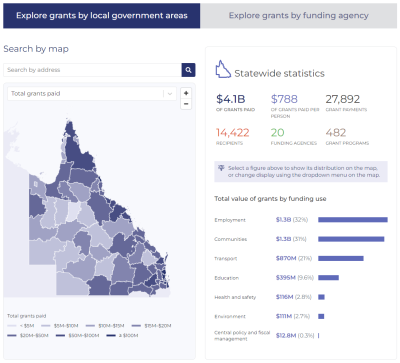

Information is available on who received grant funding and where in Queensland it was spent

In 2021–22, the Queensland Government recognised $13.2 billion in grant expenses. Grants were paid to community groups, local governments, businesses, and others, to support the objectives and priorities of the government.

Members of the public will only have confidence in the quality and integrity of the grants process if they see it as open and honest, so governments must share timely and reliable information about the grants they award. Each year, Queensland Government departments and the Queensland Reconstruction Authority publish information, on the government’s Open Data website, on funding provided for frontline services and grant programs.

Of all the expenditure they published on Open Data for 2021–22, the entities classified $4.1 billion as grants. This information is different to that reported in their financial statements, because it reflects cash payments, while financial statements are prepared under a different accounting method. Open Data also excludes grants that are paid on behalf of other entities, for example, Australian Government grants of $4.4 billion for non-state schools and local governments (which pass through Queensland Government entities before they reach their intended recipients).

In conjunction with our report Improving grants management (Report 2: 2022–23), we presented the 2020–21 grants information published on the Open Data website in an interactive map of Queensland available on our website at www.qao.qld.gov.au/reports-resources/interactive-dashboards. This has now been updated to include 2021–22 grants information. Readers can use this to explore and compare information on grants, and to access extra information relevant to understanding the local context for specific grants.

3. Results of our audits

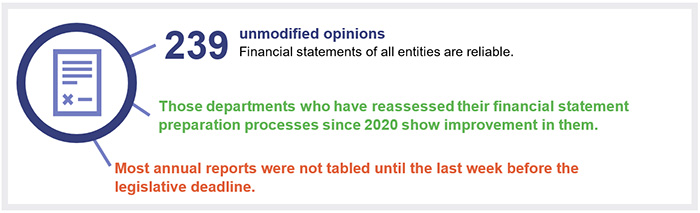

This chapter provides an overview of the audit opinions we issued for Queensland state government entities and evaluates the maturity of their financial statement preparation processes. It also provides an update on the time they took to table annual reports and make financial statements available to the Queensland community.

Chapter snapshot

Most entities signed financial statements on time, despite COVID-19

An increase in COVID-19 cases was observed throughout Queensland in 2022. For core departments, a comparison of the June 2021 and June 2022 quarters shows unplanned leave (including paid and unpaid sick leave, and carers leave) increased by nearly 700,000 hours or 15 per cent. A peak in COVID-19 cases was recorded in July, when most financial statements are prepared and audits are conducted.

We worked closely with entities and Queensland Treasury, so everyone could understand the pressures and we could respond appropriately. This included pushing some time frames out; and 12 entities were given an extension beyond the legislative deadline.

Overall, the average signing date for departments and statutory bodies (excluding category 2 water boards, river improvement trusts, and drainage boards, due to their small size) was 26 August 2022 – only one day later than in 2021. Given the challenges experienced, this was a commendable outcome for finance teams and their auditors, and demonstrates the state sector’s overall maturity in preparing financial statements.

Audit opinion results

We express an unmodified opinion when financial statements are prepared in accordance with the relevant legislative requirements and Australian accounting standards.

We issued unmodified opinions for 97.9 per cent of the 2021–22 financial statements we had audited (2020–21: 96.5 per cent) as at 28 February 2023. All the departments, government owned corporations, and most of the statutory bodies received unmodified audit opinions, which indicates the results reported in their financial statements can be relied upon.

Most entities (82.6 per cent) had their audit opinions signed within their legislative deadlines (2020–21: 89.8 per cent). Of the 12 entities that were given an extension to their deadline, one was signed within the original deadline, 9 were signed by the extended deadline, and 2 were signed shortly after the extended deadline.

Figure 3A summarises the audit opinions we issued for 244 entities for their 2021–22 financial statements, while Appendix D provides the details. For audit opinions not yet issued, Appendix H provides the list of entities.

|

Entity type |

Unmodified opinions |

Modified opinions |

Opinions not yet issued |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Departments and entities they control (controlled entities) |

37 |

– |

– |

|

Government owned corporations and controlled entities |

25 |

– |

– |

|

Statutory bodies and controlled entities |

119 |

5 |

8 |

|

Jointly controlled entities |

44 |

– |

1 |

|

Entities audited by arrangement |

14 |

– |

– |

|

Total |

239 |

5 |

9 |

Queensland Audit Office.

We included an emphasis of matter in our audit reports on 46 financial statements (2020–21: 46), with 3 entities receiving 2.

We include an emphasis of matter to highlight an issue of which we believe the users of financial statements need to be aware. The inclusion of an emphasis of matter paragraph does not change the audit opinion.

We did this to highlight that:

- only certain accounting standards were used in the preparation of 42 reports, and these reports were not intended for other users

- 2 small entities face uncertainty as to whether they will be able to pay their debts as and when they fall due

- one entity, the National Injury Insurance Agency Queensland (NIIAQ), incurred a net loss of $151.1 million in 2021–22 and had negative net assets of $384.8 million at 30 June 2022. NIIAQ provides treatment, care, and support to eligible persons injured in motor vehicle accidents. The expected cost of the treatment is recognised as a provision and is funded through levies as part of compulsory third party insurance. The provision for the financial statements is estimated using current inflation and discount rates. This differs to the longer-term inflation and discount rates used to estimate the levy charged. NIIAQ had positive operating cash flows in 2021–22, estimates positive operating cash flows in 2022–23, and as at 30 June 2022 had sufficient assets to pay liabilities expected to be settled in 2022–23

- 4 entities have either ceased operations or are likely to be dissolved in the coming year.

Modified audit opinions

We issued 5 modified opinions in 2021–22 (2020–21: 8).

We express a modified opinion when financial statements do not comply with the relevant legislative requirements and Australian accounting standards and as a result, are not accurate and reliable.

We issued 4 qualified opinions, which we do when the financial statements comply with relevant accounting standards and legislative requirements, with the exception of a specified area. These qualifications related to the valuation of and ability to prove the existence of property, plant and equipment, and also the ability to collect amounts owing.

We disclaimed one opinion, which means we were unable to express an opinion as to whether the financial statements complied with the requirements of the Financial and Performance Management Standard 2019 or the minimum reporting requirements published by Queensland Treasury.

Appendix D lists the 5 entities with modified opinions. These are small entities, being category 2 water boards, water authorities, or drainage boards.

Opinions not yet issued

Appendix H lists those entities whose audits are not yet complete. These are small entities, with most being category 2 water boards, water authorities, or river improvement trusts that did not meet the legislative deadline of 31 August.

Finalisation of overdue financial statements

We also issued 7 of the 26 audit opinions for financial statements from prior years that were outstanding as at 28 February 2022. The remaining 19 continued to be outstanding as at 31 January 2023. Of these, the audit opinion for one water authority has been outstanding since 2015–16, 2 other water authorities since 2016–17, and a river improvement trust since 2017–18.

The 7 audit opinions we issued included a qualified opinion on a small water board, relating to the valuation of property, plant and equipment. Our audit opinions of 4 other entities highlighted that only certain accounting standards were used in the preparation of reports, and these reports were not intended for other users. Of these entities, 2 also face uncertainty as to whether they will be able to pay their debts as and when they fall due, and the third entity ceased operations in 2021–22. Appendix I provides details about these audit opinions.

Other audit certifications

Appendix E lists the other audit and assurance opinions we issued, including:

- those requested by entities to provide assurance over internal controls at shared service providers (who process transactions on other entities’ behalf)

- to meet reporting requirements under grant agreements and regulatory information notices

- to meet compliance requirements under legislation, including for Australian financial services licences.

Entities exempted from audit by the Auditor-General

This year, 6 Queensland state government entities were exempted from audit by the Auditor-General (2020–21: 6). This occurs for foreign-based controlled entities where the Queensland Auditor-General has no jurisdiction or when the Auditor-General deems an entity to be small and of low risk to the Queensland Government as a whole. Exempt entities are still required to engage an appropriately qualified person to audit their financial statements. Appendix F lists the entities, and the reasons for their exemptions.

Entities not preparing financial statements

Not all Queensland public sector entities produce financial statements. This year, 142 entities were not required, either by legislation or the accounting standards, to prepare financial statements (2020–21: 141). We have identified them in Appendix G.

Exemption provided for 2021–22 to the Brisbane Organising Committee for the 2032 Olympic and Paralympic Games

In August 2022, the Under Treasurer provided the Brisbane Organising Committee for the 2032 Olympic and Paralympic Games an exemption from preparing 2021–22 financial statements. This was in response to a request from the Premier and the Minister for the Olympics. The Under Treasurer consulted with the Auditor-General in considering this request. We did not object to the requested exemption being granted given the limited financial activities of the committee in 2021–22. The committee will now prepare its first financial statements and annual report in 2022–23, covering the period from establishment on 20 December 2021 to 30 June 2023. Our annual report on Major projects will provide insights into projects associated with delivering the Brisbane Olympic and Paralympic Games.

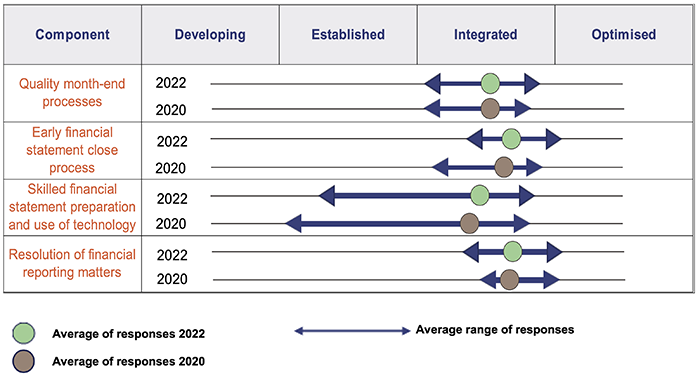

Departmental processes for preparing financial statements have improved

Over the last 2 years, 13 departments have reassessed their financial statement preparation processes using the maturity model available on our website at www.qao.qld.gov.au/reports-resources/better-practice. Figure 3B shows that, on average, each component of the financial statement preparation process has improved. This has supported the preparation of good quality financial statements in a timely manner, even when departments have been faced with the challenges presented by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Queensland Audit Office.

Our report, State entities 2020 (Report 13: 2020–21), recommended departments revisit their financial statement preparation processes, reflecting on changes made in response to the COVID-19 pandemic or machinery of government changes. Two years later, 7 departments are yet to do so. This includes 5 departments that were heavily affected by machinery of government changes in 2019–20.

Given the continued challenges faced by the public sector, it is increasingly important that financial statement preparation processes are fit for purpose.

Appendix C provides the full recommendation and status as at 30 June 2022.

Entities tabled their annual reports earlier, but could do even better

Professor Coaldrake’s 2022 Review of culture and accountability in the Queensland public sector emphasised the importance of accountability, transparency, and integrity within public sector entities. They must uphold high standards of governance and must not see governance as mere compliance.

A cornerstone of good governance is accurate and timely reporting, including publishing financial statements as soon as they are available, and not just in time to meet a legislative deadline.

In 2021–22, there was an average of 32.8 days between when the financial statements of departments and statutory bodies (excluding category 2 water boards, river improvement trusts, and drainage boards, due to their small size) were signed and when they were made publicly available. This delay is because ministers are required by legislation to table the annual reports of these entities – including their financial statements – in parliament within 3 months of the end of the financial year. Until they do this, departments and statutory bodies are not able to publish their financial information.

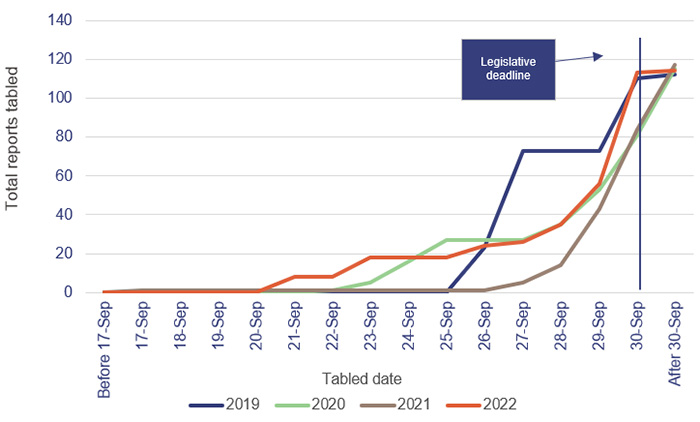

In 2021–22, the annual reports for departments and statutory bodies were tabled in parliament earlier than in recent years. In fact, 99 per cent of annual reports were tabled before the legislative deadline of 30 September 2022, compared to 72 per cent in 2020–21 and 70 per cent in 2019–20.

This was largely driven by the health portfolio, as all health entities’ annual reports were tabled on 30 September 2022. In the last 2 years, most health entities received approval from the minister to extend the tabling of their annual report due to ongoing staffing shortages from the response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The tabling of annual reports also started the earliest it has in 4 years, with 8 annual reports tabled on 21 September 2022. However, most annual reports were still not tabled until the week before the legislative deadline. Figure 3C shows this is largely consistent with previous years.

Notes: The figure excludes category 2 water boards, river improvement trusts, and drainage boards, due to their small size.

Queensland Audit Office.

This delay in publishing the financial statements reduces their usefulness to parliament and the public. Financial statements are prepared at a point in time, so the relevance of the information they contain reduces the longer it takes for them to be published. Events may also occur between the date of signing and the date of tabling that require the financial statements to be reassessed and possibly re-signed.

In 2020–21, we encouraged relevant ministers and central agencies to explore opportunities for releasing the audited financial statements of departments and statutory bodies earlier. One option we suggested was for departments to provide annual reports to the minister as they are received, to enable the minister to progressively table these reports in parliament. While this occurred for some ministerial portfolios, it was not the case for all. Figure 3D shows our analysis of tabling dates, as well as insights into events affecting ministerial portfolios.

10 ministers tabled annual reports over multiple days, starting from 23 September 2022, with an average tabling date of 28 September 2022.

Of the 7 ministers who tabled all annual reports for their portfolio on a single day, 4 tabled them on 21 September or 23 September 2022 – at least a week in advance of the legislative deadline.

One minister only had one annual report to table, and this occurred on 28 September 2022.

For 3 ministerial portfolios, while departments provided annual reports to the minister progressively, all annual reports were tabled on the legislative deadline.

One portfolio was impacted by the Queensland Energy and Jobs Plan being announced on 28 September 2022.

In 2021–22, the ministerial portfolio for health and ambulance services included 34 entities that publish audited financial statements by 30 September 2022. This is the largest ministerial portfolio. This year, the focus was on achieving the legislative deadline for the first time in 3 years.

Queensland Audit Office.

Although entities have been encouraged to table their annual reports as early as possible, Queensland Treasury and the Department of the Premier and Cabinet have not changed the formal process or deadline for tabling annual reports. An opportunity remains for Queensland Treasury to introduce legislation that allows financial statements to be published independent of the annual report, or to specify the maximum number of days between financial statement certification and tabling the annual report. Further action should also be taken by entities and ministers to streamline the process for publishing financial statements to improve the timely release of information. This will go some way towards demonstrating a genuine commitment to openness and accountability, consistent with the observations of Professor Coaldrake. Appendix C provides the full recommendations from 2020–21 and status as at 30 June 2022.

4. Internal controls at state entities

Internal controls are the people, systems, and processes that ensure an entity can achieve its objectives, prepare reliable financial reports, and comply with applicable laws. Features of an effective internal control framework include:

- strong governance that promotes accountability and supports strategic and operational objectives

- secure information systems that maintain data integrity

- robust policies and procedures, including appropriate financial delegations

- regular monitoring and internal audit reviews.

This chapter reports on the effectiveness of state entities’ internal controls and provides areas of focus for them to improve on. While we concentrate mainly on large departments, we have identified common issues that all entities should consider, and provide a case study on one statutory body that demonstrates the importance of maintaining effective internal controls during a period of change.

When we identify weaknesses in the controls, we categorise them as either deficiencies or significant deficiencies.

A deficiency arises when internal controls are ineffective or missing, and are unable to prevent, or detect and correct, misstatements in the financial statements. A deficiency may also result in non-compliance with policies and applicable laws and regulations and/or inappropriate use of public resources.

A significant deficiency is a deficiency, or a combination of deficiencies, in internal controls that requires immediate remedial action.

Chapter snapshot

Internal controls are generally effective, but entities still have common weaknesses

We assess whether the internal controls used by entities to prepare financial statements are reliable, and we report any deficiencies in their design or operation to management for action.

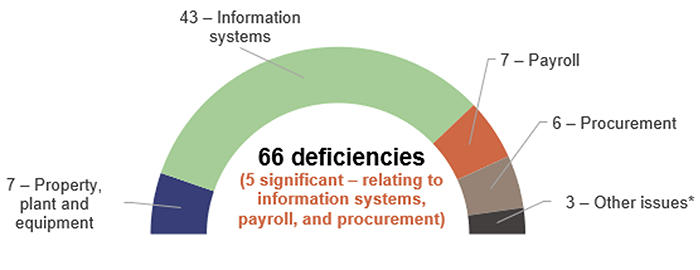

Overall, we found the internal controls that state entities have in place are generally effective, but they can be improved. While we reported fewer deficiencies to departments this year than we did last year, common weaknesses continued, with an increase in deficiencies related to information systems. Some of these have been assessed as significant and require immediate action by management.

Figure 4A shows the types of deficiencies we identified in departments.

Note: *Other issues relate to grants management, expenditure, and monitoring controls.

Queensland Audit Office.

We have received responses from each entity on planned corrective action for the internal control issues we raised. We are satisfied with the responses and proposed implementation time frames. Of the 66 deficiencies we raised, 22 have already been resolved, and work is underway to address the remaining 44.

However, over a quarter of the issues raised with departments in 2020–21 were not resolved in a timely manner. Of the 49 deficiencies from the prior year that were outstanding at the beginning of the year, 28 were resolved during the year. But 3 were reported to management again as further exceptions were identified and 18 had the original action date for resolution of the issue revised by the departments.

Proactive and timely resolution of deficiencies indicates a strong foundation for the effective operation of internal controls. Audit committees can play a critical role in overseeing the implementation of audit recommendations. In 2022 status of Auditor-General’s recommendations (Report 4: 2022–23), we highlight how audit committees can help entities to monitor their performance, hold management to account, and drive improvement.

|

Recommendation for audit committees of all entities Audit committees to actively monitor the implementation of audit recommendations (including internal audit recommendations) and encourage the timely resolution of outstanding internal control weaknesses (REC 1) |

|

We recommend that audit committees of public sector entities actively monitor the implementation of audit recommendations and encourage the timely resolution of outstanding internal control weaknesses. This should ensure the agreed recommendations address the underlying cause of the issue and issues are resolved in accordance with agreed timelines. Audit committees play an integral role in ensuring effective internal controls, including holding management to account so that identified weaknesses are resolved appropriately and in a timely manner. |

Information systems need to be protected from external attacks

Cyber threats continue to intensify in frequency and sophistication. The internet gateway (which monitors the computer traffic to and from the internet) for Queensland Government departments indicates that the number of security attempts has doubled during the year – from 750 million attempts in 2020–21 to 1.5 billion in 2021–22.

There have been some high-profile attacks on Queensland public sector entities in recent years. These attacks highlight that it is no longer if, but when a successful attack will occur. Entities must plan carefully so they can respond to and recover from a cyber attack. Our Forward Work Plan 2022–25 includes an audit topic on Responding to and recovering from cyber attacks that will provide insights and lessons learned on entities’ preparedness.

Only 33 per cent of departments have an effective system for identifying, managing, and continuously improving their response to information security risks

Since October 2018, the Queensland Government Chief Digital Officer has required departments to implement information security management systems (ISMS) and report on their progress. An ISMS is a systematic approach to identifying and managing information security risks, in accordance with the ISO 27001 Information Security Standard.

While the ISMS maturity of the Queensland Government shows evidence of improvement, the improvement needs to occur at a faster pace. In 2020–21, only 33 per cent of departments reported an operating level ISMS (where risks are identified, managed, and continuously improved) versus the target of 100 per cent set by the Queensland Government Customer and Digital Group. The ISMS report for 2021–22 had not been finalised at the time of our report.

Our audits focus on the information systems that public sector entities use to prepare financial statements. It is important the same security principles are applied to all systems used by public sector entities, including systems that are managed on their behalf by external service providers.

These systems hold a significant amount of sensitive information about people and entities who interact with the Queensland Government, which makes them attractive to external attackers. Any security incidents affecting these systems, regardless of whether they are managed internally or by external service providers, can also expose systems that are connected to them. Departments are accountable for the security, confidentiality, integrity, and availability of these systems, but a department’s overall security is only as strong as its weakest link.

Weaknesses exist in user access and system security

Consistent with last year, we continue to recommend departments implement appropriate controls over access to their systems (user access) and system security to protect their information systems. Figure 4B outlines the 3 main areas that departments need to address.

|

Managing privileged (system administration) access |

Access to system administration allows users to make significant changes to system configuration, bypass security settings, or access sensitive information. The Australian Cyber Security Centre identifies the restricting of system administration access as one of the most effective strategies to mitigate against cyber security incidents. We reported issues in relation to:

|

|

Configuring security |

Departments need to update their assessment of security risks and practices as technology advances and security loopholes are discovered. We identified the following common weaknesses during the year:

|

|

Managing user access |

The security of information systems relies on departments providing access to the systems only to users who need it to perform their job roles. We continue to observe:

|

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office from management reports issued to departments.

We recommend all entities continue to act on the recommendation from our report last year to strengthen the security of their information systems. Appendix C provides the full recommendation and status as at 30 June 2022.

Departments need to have specific controls in place when they use a shared service provider

Most of the departments use a shared service provider to provide a range of payroll, accounts payable, and information technology infrastructure services. While the shared service providers process transactions on behalf of departments, the departments are responsible for ensuring they have complementary controls in place and that they are operating effectively.

Complementary controls are used when a transaction is initiated within a department (for example, by ensuring supporting documentation is accurately completed and approved by someone with appropriate financial authority) and after a transaction is processed by a shared service provider (for example, by having department employees check reports for errors or fraud).

Independent checks of changes to supplier details

In State entities 2021 (Report 14: 2021–22), we reported significant deficiencies relating to a lack of independent checking of changes to supplier details by departments before they were processed by a shared service provider. This increases the risk of fraudulent changes to bank account details.

While not all departments have fully resolved this issue from last year, we have seen improvements in this control, and we did not identify any further deficiencies relating to supplier changes this year.

Payroll controls

Last year, we also reported deficiencies relating to:

- inconsistent approval and lack of evidence for additional employee payments, such as overtime and higher duties

- a lack of review of payroll reports by departments.

Some of the departments who had these specific issues last year have had similar issues raised this year, meaning they have not appropriately acted on the recommendations.

We reported a significant deficiency to one department, as the lack of review of payroll reports resulted in overpayments to an employee over a 13-month period. The overpayments would have been identified earlier if the payroll reports had been reviewed in a timely manner. This control weakness had previously been identified in this area of the department, but machinery of government changes meant it had not been adequately resolved.

This year, in some instances, we also found departments did not have an appropriate policy or procedure in place that outlined the required process for approving employee payroll transactions or reviewing payroll reports. This lack of guidance reduces the effectiveness of payroll controls, increasing the risk that errors or fraudulent transactions (such as invalid payments for overtime, higher duties, or allowances) will not be detected.

Consistent with last year, we recommend all entities implement appropriate policies and procedures to support the approval of payroll transactions and timely review of payroll reports. Appendix C provides a full list of prior year recommendations and their status as at 30 June 2022.

Improvements need to be made to procurement and contract management processes

This year, we again identified weaknesses in procurement and contract management practices across departments. Among them was one significant deficiency relating to breakdowns in the procurement and contract management process, including:

- not having an appropriate system or consistency for managing agreements

- inconsistent or insufficient evidence of financial approval, including one instance where an agreement was approved above the approver’s financial delegation

- instances where no agreement was in place or where agreements were not signed.

Other common deficiencies we identified across departments included:

- the lack of an appropriate centralised system ensuring consistency across the department for managing contracts

- non-compliance with specific requirements of the Queensland Procurement Policy 2021. An example of this is the requirement to publish details of awarded contracts within 60 days of the contract award date

- instances where key procurement policies and procedures had not been reviewed or updated in a timely manner.

In Contract management for new infrastructure (Report 16: 2021–22), we emphasised the need for departments to have an appropriate system to record and manage contracts. Along with complete and accurate contract registers, these are essential to enabling efficient and effective monitoring and reporting on contract progress and performance.

To achieve value for money from their purchasing activities and ensure compliance with the Queensland Procurement Policy 2021, departments need effective procurement and contract management practices, supported by current policies and manuals.

Consistent with last year, we continue to recommend departments ensure they have appropriate policies and manuals to support their procurement and contract management practices. Appendix C provides a full list of prior year recommendations and their status as at 30 June 2022.

Internal controls during a period of change

Effective internal controls rely on people, systems, and processes working together to ensure an entity can achieve its objectives, prepare reliable financial reports, and comply with applicable laws. Change in any of these components increases the risk of internal controls not operating effectively. This can occur when there is a change in leadership, a new system is implemented, employee turnover is high, or processes are not accurately documented. This was the case at the Queensland Building and Construction Commission in 2021–22, as described in Case study 3 in Figure 4C.

| High turnover at the Queensland Building and Construction Commission weakened internal controls |

|---|

|

The Queensland Building and Construction Commission (QBCC) is responsible for independently regulating the building and construction sector, and for managing Queensland’s home warranty insurance fund. In November 2021, the Department of Energy and Public Works commissioned an independent review into QBCC governance arrangements. The review – QBCC Governance Review 2022 – used a number of sources, including the QAO report Licensing builders and building trades (Report 16: 2019–20). It reached conclusions and made recommendations consistent with those of reviews conducted several years earlier. It noted that the QBCC is operating in a challenging environment. Successive governments had expanded its role and responsibilities, and it had lost several senior leaders. In 2021–22, 19 different people worked in 9 key management personnel roles. It also had a 14.7 per cent staff turnover (with a base of 511 full-time equivalent employees). This meant many staff members were in acting roles for extended periods and taking on extended responsibilities. This affected culture, structure, and the reporting to senior leadership and the board, which in turn affected the decisions made. The challenges were particularly felt in procurement and payroll. They relied on short-term support to manage regular operations. Many of the decisions being made – such as the need for rapid turnaround of contracts for consultants, staff, or services – were not supported by sufficient resources and processes. We reported 2 significant deficiencies relating to procurement and payroll processes:

These deficiencies were caused by high staff turnover, which affected people’s capacity and capability, and meant policies and procedures were not appropriately understood across the business. Queensland Treasury approved an extension to the legislative deadline. This provided QBCC with additional time to finalise its financial statement preparation and audit, so the required information could be collated and reviewed, and additional audit procedures could be performed. This work was completed within the time frames allowed by Queensland Treasury, and we issued an unmodified opinion for the financial statements of the QBCC. Since then, QBCC has updated its policies and procedures to align to the needs of the business and relevant government requirements. It has made permanent appointments in senior leadership roles. It is continuing to focus on records management policies and practices and on developing systems to meet these requirements. Our 2022–23 audit will focus on testing the implementation of these changes, and the effective operation of internal controls within procurement and payroll. Other areas in government are facing challenges associated with higher turnover of staff, changes in their roles and responsibilities, and policies that may not be supporting their current (or future) circumstances. They need to understand and manage their processes through clearly documented policies and procedures, and provide appropriate training for new and existing staff. They also need to monitor these areas to promptly identify any concerns around staffing or the effective operation of internal controls. |

Prepared by the Queensland Audit Office from management reporting to the Queensland Building and Construction Commission.

Understanding grants dashboard

Our interactive dashboard allows you to explore and compare information on government grants in Queensland by local government area and funding agency. It also includes extra information relevant to understanding the local context for specific grants.