Overview

Governments use industry development programs to grow particular sectors, attract private investment, and create jobs. When designed and delivered well, these programs can generate strong economic and social benefits. But if not managed well, they can carry risks, such as suppressing competition or not achieving value for money.

We assessed whether the Department of State Development, Infrastructure and Planning designed, administered, and evaluated the program to achieve its objectives. We also examined how the department managed engagement with the private sector while maintaining financial accountability, and how it monitored and evaluated program outcomes.

Tabled 28 October 2025.

Report summary

This report examines the effectiveness and probity of the Industry Partnership Program in supporting industry development in Queensland. The program is administered by the Department of State Development, Infrastructure and Planning.

What is important to know about this audit? |

- Governments use industry development programs to grow particular sectors, attract private investment, and create jobs. Queensland’s approach to this reflects national and international trends.

- When public sector entities design and deliver these programs well, they can generate strong economic and social benefits. But if not managed well, they can carry risks, such as suppressing competition or not achieving value for money.

- The Industry Partnership Program (the program) was delivered by the Department of State Development, Infrastructure and Planning (the department) from June 2021 to June 2025. The program included $330.1 million for grants which aimed to create jobs, strengthen Queensland supply chains, and attract private investment. The program focused on priority industries like medical technology, critical minerals, and battery technology.

- The department approved $204.5 million for 30 projects. Some funds remain uncommitted, including $75 million for projects approved in principle but not yet finalised. While the program has closed to new applicants, the approved projects are still being delivered.

What did we find? |

The program was well designed to support Queensland’s industry development objectives

- It supported government strategies, clearly outlined its purpose and expected outcomes, and attracted strong industry interest.

- The department updated the program’s guidelines over time to reflect internal reviews and policy changes, keeping the program relevant.

The probity and administrative controls over the program were strong, but improvements could be made to future programs

- The application, assessment, and approval processes were generally fit for purpose. The use of a cross-agency governance model added expertise and rigour to decision-making.

- A small number of high value projects did not follow the program’s standard assessment and endorsement process. This reduced funds available for competitive applicants and meant these projects were not assessed in the same way.

- In 2023, the department updated its assessment criteria but gave limited guidance to assessors. This made some approval decisions difficult to understand.

- The department did not adapt its detailed compliance checks to the risks of different projects, creating unnecessary burden for grantees and the department.

Program processes lacked flexibility, which made it hard for some suitable businesses to participate

- The department did not define the level of risk it was prepared to accept in supporting newer or smaller businesses. As a result, it applied the same criteria to all projects. By not clearly defining its risk tolerance and criteria for newer or smaller businesses, the department created the potential for some applicants to be unnecessarily excluded or rejected.

The program showed some positive initial outcomes, but the department could have tracked and reported results better

- The department collected data on jobs created, private investment, and supply chain spending. It did not set program-level targets for these outcomes, making it difficult to measure progress or success.

- It did not develop a monitoring and evaluation framework at the outset and relied on self-reported, unverified information from grantees for some outcomes. As a result, broader impacts, such as supply chain and industry-wide benefits, were hard to assess.

- The department did not conduct economic modelling to assess the program’s overall impact.

Public reporting on government support for private businesses needs to increase

- Funding agreements included confidentiality clauses to protect business information. While this encouraged participation, it also reduced transparency by limiting what could be reported publicly.

What do entities need to do? |

We have made 8 recommendations, mostly directed to the Department of State Development, Infrastructure and Planning. Two apply to all entities involved in administering government grant programs. The recommendations focus on the following themes:

- making grant processes clearer, more consistent, and better matched to the size and risk of each project

- ensuring entities clearly explain how much risk they are willing to accept to achieve policy intent, and reflect this in the grant processes

- improving how results are measured by setting clear goals and success indicators and using economic analysis to check if programs are delivering value.

The department has agreed to all recommendations.

Audit conclusions

The Department of State Development, Infrastructure and Planning (the department) effectively administered the Industry Partnership Program (the program) and aligned it with government priorities for industry development.

The program supported key industries – such as critical minerals and biomedical manufacturing – and used defined assessment steps, strong governance, and sound probity controls. These features helped attract widespread interest from industry and supported projects that were in line with Queensland’s broader economic development goals.

However, the department has not clearly demonstrated the program’s overall effectiveness. It collected useful project-level data and tracked outputs such as jobs and investment, but it did not set program-level targets or develop a framework to measure and report outcomes. It also did not publicly report any program results, which reduced transparency.

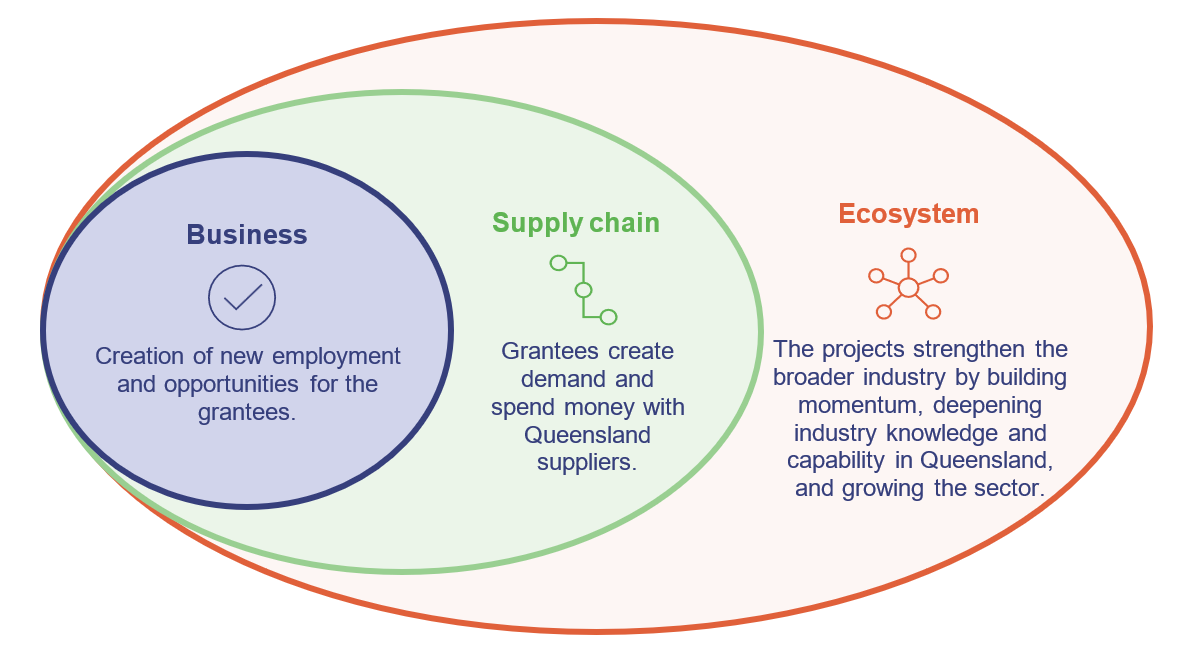

The program also aimed to deliver broader benefits. These included more spending with Queensland suppliers – referred to as supply chain impacts – and longer-term contributions to the growth of related industries, which it refers to as ecosystem impacts.

The department relied on information reported by grant recipients to assess project outcomes. It did not consistently check the accuracy of this data or combine it to assess trends across the program.

We identified areas for improvement to strengthen future grant delivery. These include enhancing risk planning and monitoring and applying assessment and approval processes more consistently. The department could strengthen its evaluation and reporting practices to improve accountability and guide future initiatives.

Although the program has closed to new applications, the department continues to deliver approved projects. It also continues to develop new grant initiatives. By applying lessons from this program, it can better advance Queensland’s industry development goals and increase transparency across future programs.

2. Recommendations

We have directed the recommendations in this report to the Department of State Development, Infrastructure and Planning (the department), except for 2, which apply to all entities.

| Strengthening risk, application assessment, and compliance processes | Entity responses |

| We recommend that the department: | |

| Agree |

| Agree |

| Agree |

| Ensuring grant processes reflect program intent and the program is publicly accountable | |

| We recommend that all entities: | |

| Agree |

| Agree |

| Monitoring, evaluating, and reporting performance | |

| We recommend that the department: | |

| Agree |

| Agree |

| Agree |

Reference to comments

In accordance with s. 64 of the Auditor-General Act 2009, we provided a copy of this report to the department. In reaching our conclusions, we considered its views and represented them to the extent we deemed relevant and warranted. The formal response from the department is at Appendix A.

3. Industry development in Queensland

What is industry development?

Industry development refers to how governments create conditions that help achieve broader public goals and help private businesses grow.

Governments may direct support when private capital is unlikely to flow into sectors or regions with broader community benefits, such as biomedical projects in regional areas or businesses making low-emissions products. These benefits can often be long-term and may not deliver immediate financial returns.

In such cases, governments at the state and federal level may offer targeted support through a mix of levers depending on their objectives and the needs of each industry. The aim is to encourage investment and stimulate growth, while avoiding practices that affect competition or keep uncompetitive businesses operating. Figure 3A shows the levers available.

Grants |

| Loans and equity |

|

Subsidies |

| Business facilitation |

|

Tax incentives |

| Procurement and regulation |

|

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office.

Why are probity safeguards in industry development important?

Targeted support for industry can bring economic and social benefits. It can create jobs, support regional growth, strengthen supply chains, and attract private investment.

However, industry development programs also bring risks that need to be managed. Programs to support private businesses must be well designed, transparent, and accountable to ensure public funds are used effectively and for the public benefit. Public sector entities administering these programs must have strong probity safeguards in place to maintain public trust, ensure fair access to funding, and protect decisions from perceptions of bias or undue influence.

How does the Queensland Government support industry development?

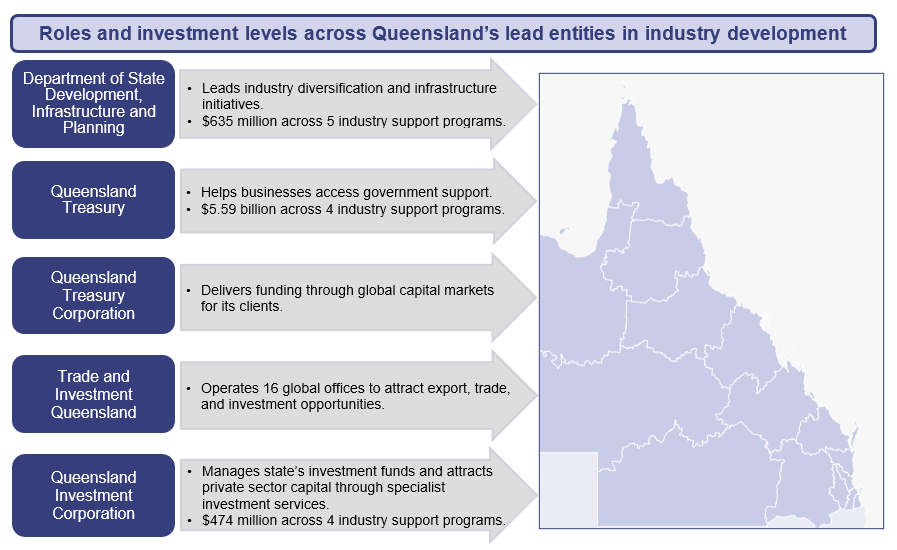

The Queensland Government supports industry development in a range of ways, including grants, loans, and business facilitation services. Multiple departments and programs deliver this support, often working together to grow or support strategic sectors and regional economies.

The Department of State Development, Infrastructure and Planning (the department) plays a central role in this. It works with specialist entities such as Trade and Investment Queensland and the Queensland Treasury Corporation to coordinate support and advance government priorities.

Figure 3B shows the key public sector entities involved in industry development at the time of the Industry Partnership Program. It highlights their roles and the type and level of investments they deliver.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office using information from the relevant entities’ reports relating to industry development.

The department’s role in industry development

The Department of State Development, Infrastructure and Planning leads many of Queensland’s industry development activities. It works with other entities and businesses to attract investment and grow priority sectors, such as critical minerals, medical technology, and the bioeconomy.

Its responsibilities include advising government on policy, designing programs, and helping businesses prepare proposals when seeking investment support. It also collaborates with regional stakeholders to coordinate local growth with state priorities.

The department supports industry development by:

- providing grant funding for strategic projects

- offering tailored support to help businesses attract investment, such as connecting them with investors or providing advice

- coordinating major cross-agency initiatives

- undertaking long-term planning through roadmaps and action plans.

This approach is designed to ensure government support is targeted, evidence-based, and consistent with Queensland’s long-term development goals.

What is the Industry Partnership Program?

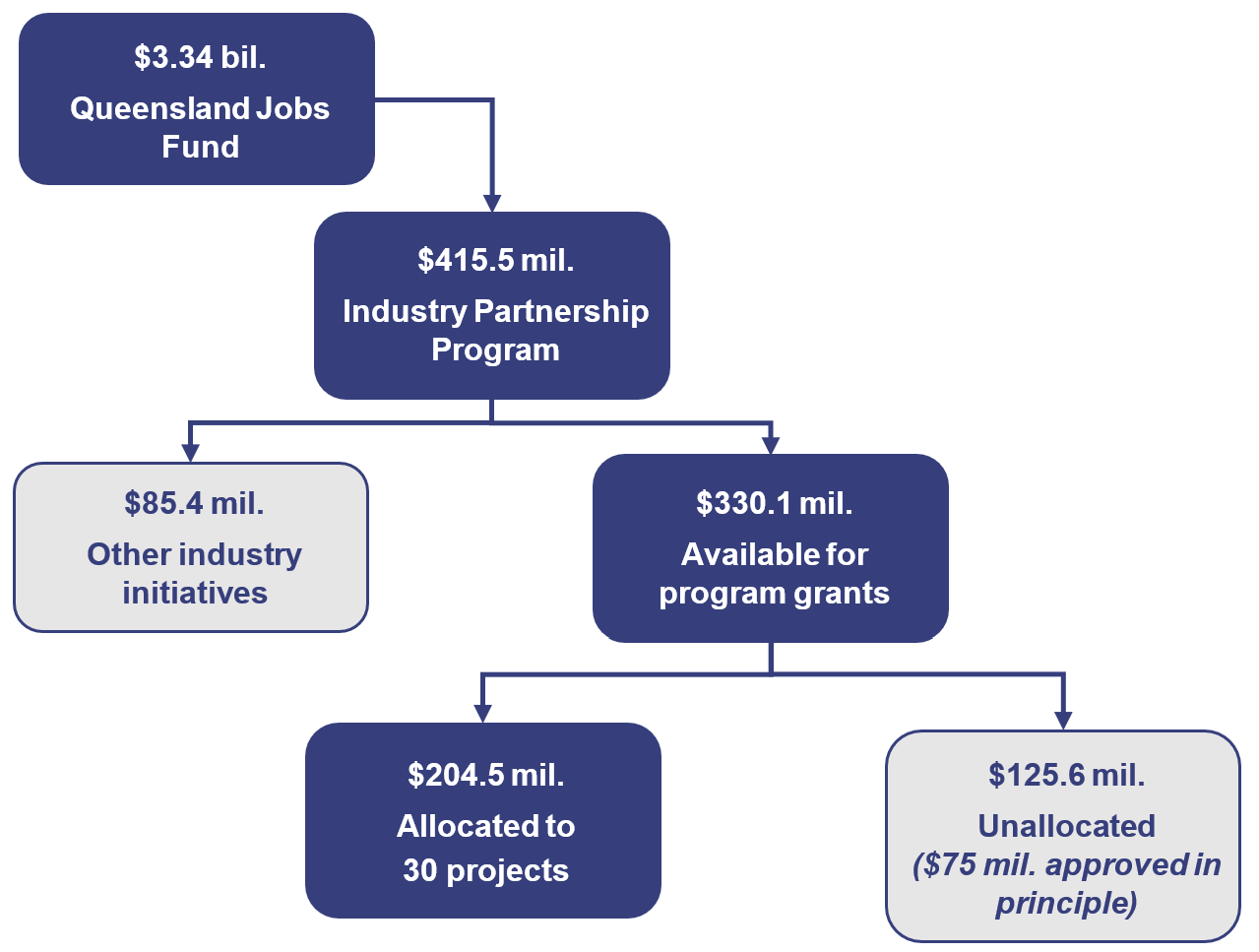

The Queensland Government launched the Industry Partnership Program (the program) in June 2021 under the $3.34 billion Queensland Jobs Fund. The program funding was $415.5 million. Its aim was to support industry development by encouraging private sector investment, strengthening supply chains, and creating jobs across the state. Figure 3C shows how the total program funding was allocated.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office using data from the Department of State Development, Infrastructure and Planning.

Of this funding, government directed $85.4 million to related industry initiatives delivered outside the program. This included investments in targeted funds like the Building Acceleration Fund, which supports infrastructure for job-creating projects, and the Hydrogen Industry Development Fund, to help develop Queensland’s hydrogen industry.

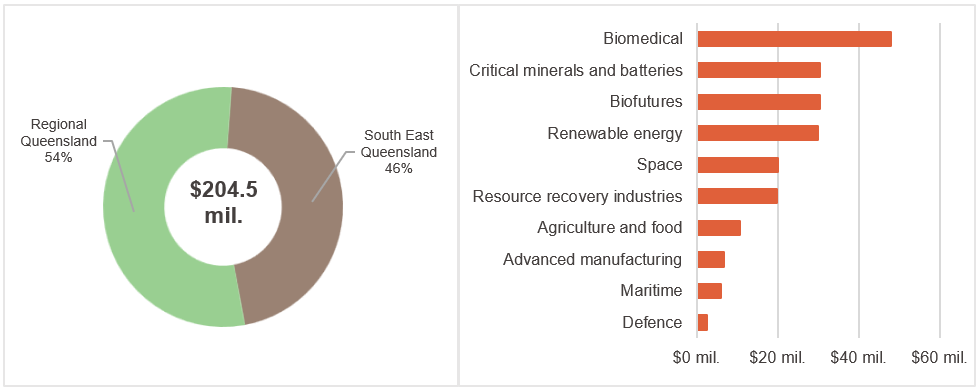

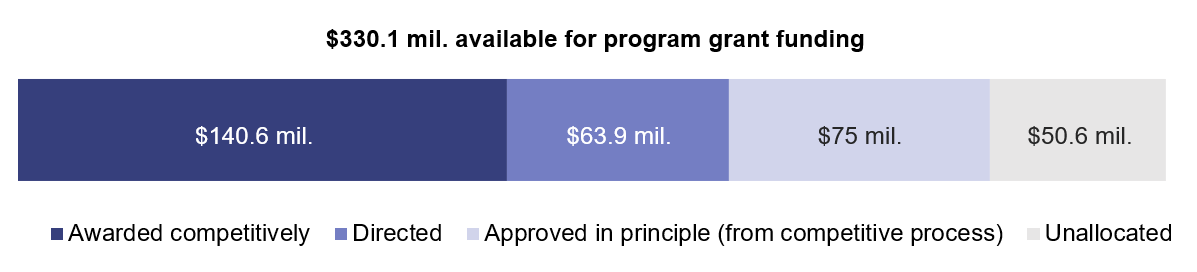

This left $330.1 million for program grants. The department committed $204.5 million for 30 approved projects across industries and across the state, as shown in Figure 3D. It has not yet agreed with government how to finalise the remaining uncommitted funds, which include $75 million for projects approved in principle but not yet formally approved. While the program has closed to new applicants, the approved projects are still being delivered.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office using data from the Department of State Development, Infrastructure and Planning.

What we audited

This audit focused on the effectiveness and probity of the grant component of the program. Although the government closed the program during the audit, it can apply the learnings from the audit to future or ongoing programs.

We selected this program for audit because:

- It was sizeable in value as the fourth-largest industry development fund in Queensland.

- It had been running since 2021, allowing enough time to assess early impacts.

- There was limited public information available about how effective it had been.

We reviewed program documentation, performance reports, and decision-making processes. We also examined a sample of successful and unsuccessful project applications.

Appendix B provides greater detail on our audit scope and methodology.

4. Designing the program

The design of grant programs has a direct impact on their effectiveness and the ability of departments to administer them fairly and efficiently. Key aspects of good design in Queensland include:

- clear links between the program and government policy objectives

- elements of better practice relevant to the sector

- defined and measurable objectives and outcomes, with agility to adjust the program in response to interim results

- internal procedures that comply with the Queensland Treasury’s Financial Accountability Handbook.

Programs that operate in line with better practice build on these elements by actively engaging stakeholders, targeting support where it’s most needed, and adapting when policy priorities shift or interim results show a need for change.

In this chapter, we report on how well the design of the Industry Partnership Program (the program) reflected these principles, focusing on alignment with government objectives, use of better practice, clarity of objectives and measures, and guidance for staff.

Did the program’s design align with government objectives?

The Department of State Development, Infrastructure and Planning (the department) designed the program to support Queensland’s industry development goals. It initially targeted the priority industries captured by Unite and Recover: Queensland’s Economic Recovery Plan.

The program’s objectives included encouraging private investment, creating jobs, and strengthening supply chains – the network of suppliers and services that support the delivery of projects. These objectives were consistent with government efforts to grow the state’s industries.

The department updated the program guidelines to reflect shifts in policy

The department revised the program guidelines twice – first in 2022 to clarify intent, and again in 2023 to reflect updated government priorities.

The 2023 update had 2 parts:

- It limited funding to capital expenditure for ‘shovel-ready’ projects, shifting the focus away from early-stage research. This allowed the program to support projects that were ready to start quickly, and matched investment and job creation priorities.

- It required that eligible projects be in one of the 7 industries outlined in the government’s Queensland New Industry Development Strategy (released in 2023) and Biomedical 10-Year Roadmap and Action Plan (released in 2017). These industries were:

- critical minerals

- battery technology

- renewable energy manufacturing

- green hydrogen

- bioeconomy

- biomedical industries

- circular economy, including resource recovery and recycling.

In 2023, the government also introduced a $12 million sub-stream for the Cairns Marine Precinct. This was separate from the main program changes but aligned the program to support regional development priorities in the defence and marine sectors.

These changes demonstrate how the department kept the program aligned with Queensland’s economic priorities by focusing on projects that delivered jobs, private investment, and industry growth.

The program’s design included better practice elements but had limited structured consultation

The department incorporated several better practice elements into the program’s design, drawing on its experience in delivering previous industry development grants.

Better practice for industry development grants is still emerging, but the program showed similarities to comparable initiatives across Australia. These included clearly defining priority sectors for investment, requiring grantee co-investment, and outlining intended outcomes such as creating jobs and attracting private investment.

Better practice for grants management more generally is well established, and the program met most of these features. The program guidelines clearly specified eligibility requirements, assessment criteria, and accountability mechanisms. They were consistent with the Queensland Treasury’s Financial Accountability Handbook and the department’s Grant Management Framework. The program also used established governance processes, including cross-agency assessment panels and clear approval pathways.

However, the department did not have a documented engagement approach – a formal plan for how and when it would consult with stakeholders during the design of the program. While it held internal policy discussions and briefed its regional and sectoral teams, it did not seek direct input from industry stakeholders at the design stage. Instead, it relied on lessons learned from previous programs.

The Commonwealth Grants Rules and Principles 2024 emphasise the importance of collaborating with stakeholders when designing grant programs. Involving government and non-government stakeholders can improve program relevance, avoid overlap with other initiatives, and tailor programs to user needs.

Limited consultation contributed to an underestimation of demand and delays in assessment

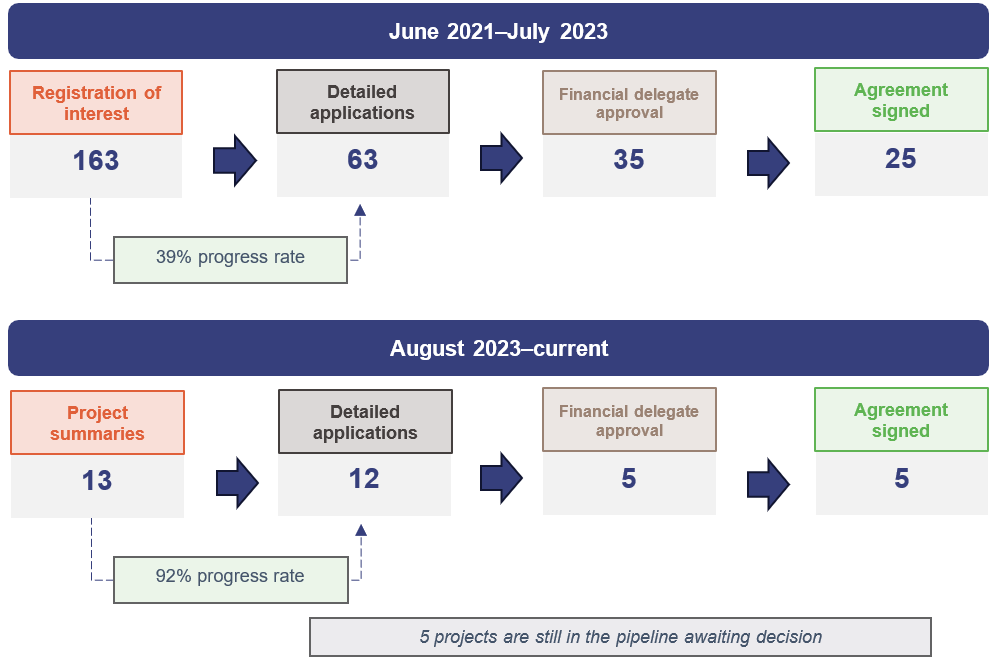

Despite the absence of this consultation, the program attracted strong and widespread interest. In its first 2 years, the department received 163 registrations of interest, which resulted in oversubscription and delays in assessment.

This high demand shows that the program met a market need. Engaging stakeholders during the design phase could have helped the department gauge the amount of stakeholder interest. It could also have helped it to better communicate the intent of the program and manage demand.

Were the program’s objectives and success measures clearly defined?

Grant programs are more effective when they have clearly stated objectives and a way to measure if those objectives are being achieved. This supports transparency, accountability, and meaningful evaluation.

Programs that follow better practice set measurable indicators of success and show how activities, such as funding projects or supporting industries, are expected to lead to specific results.

The department set clear objectives, but it did not define measures of success

The department clearly outlined the program’s purpose and objectives in all 3 versions of its guidelines. These consistently focused on attracting private sector investment, creating jobs, and strengthening supply chains in Queensland’s priority industries.

The department did not formally set performance targets for the program’s key intended outcomes. While the government publicly announced that the program would create 2,800 jobs, there is no record of how this figure was calculated during the design of the program. The department did not actively track progress against this target.

The department did not set performance targets for other key outcomes, such as:

- the amount of funding contributed by private businesses or other governments

- supply chain expenditure.

While individual project agreements included outcome requirements such as job creation and investment, there was no program-level target to work towards or track against. Without clear benchmarks or defined targets, it is difficult to assess whether the program achieved its intended objectives.

The Queensland Audit Office’s Grant management maturity model, developed after research into grants management frameworks in Australia and overseas, highlights that higher-performing programs have specific, measurable objectives and define their criteria for success. Stronger programs develop these measures early on to track the impact of grants and how well they reflect government priorities.

We discuss success measures and targets further in Chapter 6.

Did the department provide guidance to its staff on how to run the program?

Grant programs should provide clear and current guidance to support consistent delivery. This guidance should reflect key frameworks, like the Queensland Treasury’s Financial Accountability Handbook, and should help staff apply processes consistently, manage risks, and ensure accountability.

The department provided clear internal guidance for most program processes

The department developed detailed procedures to guide staff in delivering the program. The procedures aligned with the department’s Grant Management Framework and Financial Management Practice Manual, reflecting the Queensland Government’s expectations for grant delivery.

The department updated its procedures when the program changed, ensuring staff had access to current instructions. The procedures were clear but guidance for assessing applications in the later stages of the program could be improved. We discuss this further in Chapter 5.

The program’s risk assessment process was sound but not comprehensive

The department compiled a risk register covering several operational risks, including staff resourcing, conflicts of interest, assessment delays, and stakeholder concerns, but did not include:

- fraud

- applicants receiving funding for the same project from multiple government programs.

The Financial Accountability Handbook advises entities to consider these risks when planning and delivering grant programs.

The risk of fraud could arise through applicants providing false or misleading information, overstating project costs, or not using funds as intended. Similarly, applicants could seek support for the same project from multiple sources, including other state or federal grants, without disclosing this to program administrators.

The department implemented controls to reduce these risks, such as conducting due diligence checks and requiring declarations in applications. However, it did not explicitly document these risks, and how they would be managed, in the program’s risk register.

This weakened its ability to clearly link these risks to relevant compliance activities, such as adjusting evidence requirements or acquittal processes based on a project’s risk profile. We discuss this further in Chapter 6.

Recommendation 1 We recommend that the department strengthens its risk assessments for grant programs by including the risk of fraud and the risk of applicants receiving funding from different government sources for the same projects. |

5. Administering the program

To deliver grant programs well, departments must have clear processes, make fair decisions, and use public funds effectively. In this chapter, we report on how the Department of State Development, Infrastructure and Planning (the department) administered the Industry Partnership Program (the program), focusing on whether it:

- effectively promoted the program

- fairly and consistently assessed applications

- established clear and balanced agreements with recipients.

How well did the department promote the program?

To be fair and successful, grant programs need to ensure eligible industries and regions have an equal opportunity to apply. This requires a clear approach to promotion. Entities also need to monitor how well their programs are reaching potential applicants.

The promotion was targeted, but there was no strategy or monitoring of who it was reaching

The program was visible to the public through ministerial announcements, the department’s website, and the government’s grants portal. The department promoted the program mainly through its regional and sectoral teams, and other government entities, which identified suitable applicants via their industry networks.

This targeted approach suited the program, which had relatively narrow eligibility and assessment criteria. However, the department did not develop a promotion strategy and did not monitor the reach or effectiveness of its promotional activities. Relying on existing networks meant that businesses with established relationships were more likely to be invited to apply. The department did not demonstrate how it ensured equal access for businesses without these connections.

Without a strategy, it was hard to arrange and coordinate promotional activities, identify gaps – such as newer or less-connected businesses that were missed – or define what success looked like. While the department monitored businesses at the assessment stage, it did not track those that showed interest but did not proceed further. This left the department uncertain about the reach of its promotional activities.

A clear promotion strategy supported by monitoring could have improved visibility on program reach, helped ensure fair access, and strengthened overall transparency.

Was the application and assessment process fair and consistent?

Fair, transparent, and consistent application and assessment processes contribute to maintaining the integrity of government grant programs. These processes should be guided by the Queensland Treasury’s Financial Accountability Handbook to help ensure decisions are based on detailed information, documented, and based on merit.

After the 2023 changes to the program, the application process improved, but assessment became more subjective

The department initially implemented an open registration model, where any business could register interest at any time. This meant the department had to assess and respond to many expressions of interest that were ineligible or unsuitable for the program.

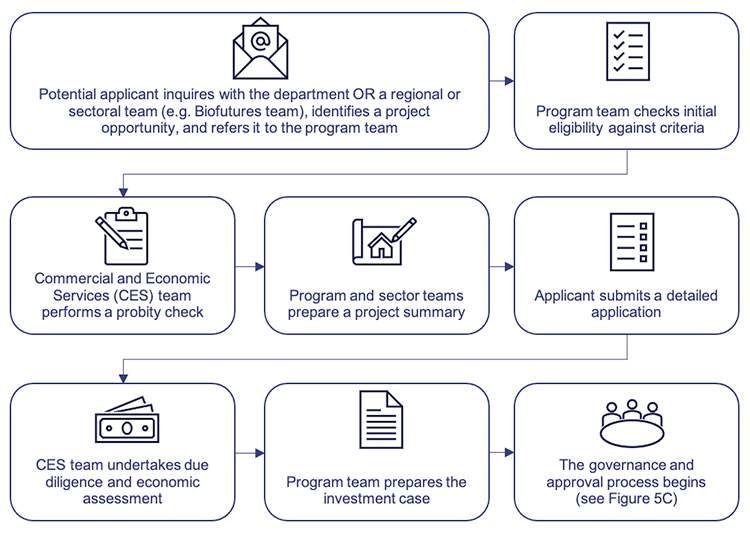

In 2023, the department refined its approach by replacing the open registration model with a more selective process. Prospective applicants were required to engage with the department before being invited to apply. Applications then progressed through a multi-stage process for assessment, as shown in Figure 5A.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office using information from the Department of State Development, Infrastructure and Planning.

This new approach improved the decision-making process and gave the department greater control over the type and quality of applications progressing through the process. This strengthened the connection to strategic goals and helped in managing assessment workloads. Figure 5B shows the shift in application volumes and progress rates before and after this change.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office using data from the Department of State Development, Infrastructure and Planning.

The department did not consistently provide a clear rationale for who it invited to apply

In both versions of the process, the department used a spreadsheet to track program inquiries, and the reasons businesses were, or were not, invited to apply. However, it did not consistently record a rationale or have a process to ensure decisions were impartial. This created a risk that invitations could be influenced, or perceived to be influenced, by factors outside the program’s intended criteria.

Having a consistent and transparent method of documenting outcomes would have improved accountability and reduced probity risks. This is particularly important where applicants are invited to apply.

The assessors needed clearer guidance once the eligibility criteria changed

While the process was generally sound, the 2023 changes introduced broader eligibility criteria and a stronger emphasis on emerging industries, such as battery technology and critical minerals. These changes introduced more qualitative criteria.

Staff used standard templates to assess applications against the program criteria. The templates lacked detailed guidance or scoring frameworks, particularly for complex concepts such as economic impact and project benefits. This increased subjectivity and variability in how individual assessors interpreted and applied criteria.

Better guidance and scoring tools would improve transparency and reduce the risk of inconsistent assessments.

Recommendation 2 We recommend that the department improves the consistency and transparency of grant assessments by ensuring assessment frameworks include clear guidance for assessors, particularly for qualitative criteria such as a project’s potential to drive economic change. |

The assessment of whether projects needed government funding improved over time

A key consideration for grant funding is ‘additionality’ – whether a project would proceed without government support. In early assessments, the department did not consistently assess or record its rationale for additionality. This limited its ability to demonstrate that funded projects provided public value beyond what would have occurred without support.

As the program matured, the department improved its approach. It revised assessment templates to include prompts about additionality and provided clearer instructions for staff on documenting why a project needed government funding. This helped improve the defensibility of decisions and was consistent with better practice for demonstrating value for money.

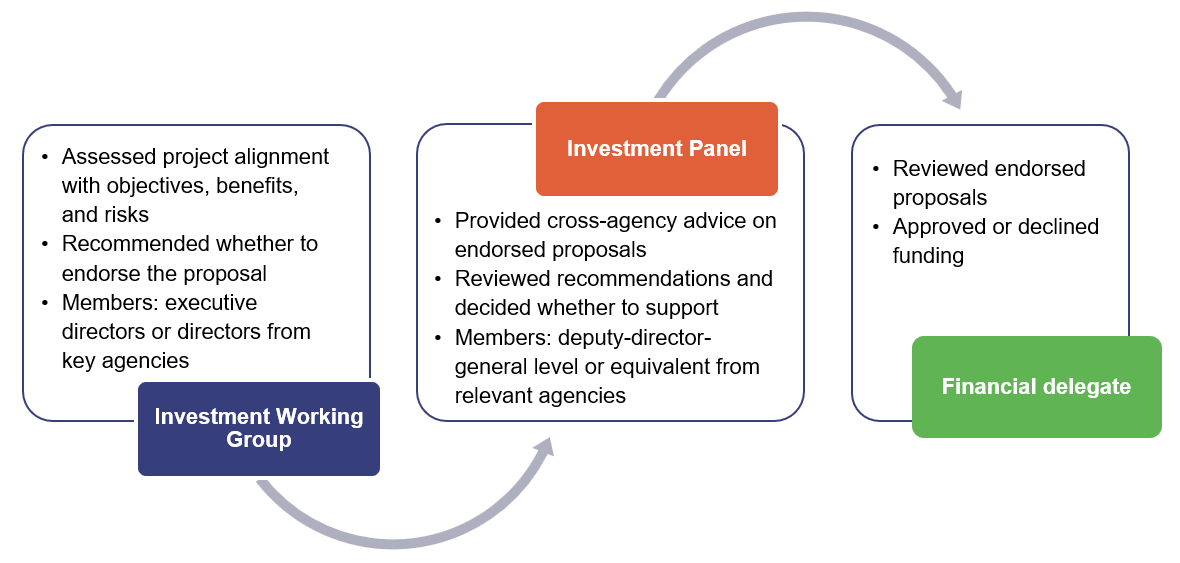

The governance arrangements provided expertise and rigour

The department used a 2-tier governance structure to assess and endorse applications. The Investment Working Group and the Investment Panel included senior executives and representatives from relevant government entities.

These bodies existed prior to the program and reviewed applications for several other industry development programs. This increased the objectivity and industry insight the program applied to the applications.

For the program, these 2 bodies reviewed assessment findings, endorsed recommendations, and recorded outcomes in formal meeting minutes. This structure reflected better practice and added rigour to decision-making. Figure 5C outlines how the various bodies worked together to make decisions about projects and funding.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office using information from the Department of State Development, Infrastructure and Planning.

The department could strengthen its processes for identifying conflicts of interest

The department required assessors and panel members to declare any actual or perceived conflicts of interest. However, it did not maintain a central register across all stages of the assessment and approval process. This made it difficult to confirm that all conflicts were consistently identified and managed.

A central register would provide clearer oversight, improve transparency, and reduce probity risks, particularly where staff were involved across multiple stages of assessment and approval.

Some funding decisions did not follow the program’s prescribed assessment process

The department is responsible for administering the grant program. Governments can also award grant funding in ways that differ from program guidelines. In these cases, the department should clearly document the rationale, risks, and value-for-money considerations for these projects.

In the sample we assessed, the government directed 3 projects to be funded through the program. Together, these projects received around one-third of the program’s total funding committed at that time as shown in Figure 5D below.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office using data from the Department of State Development, Infrastructure and Planning.

The department clearly documented the required information for these projects in submissions to government, demonstrating compliance with the Queensland Treasury’s Financial Accountability Handbook. The department then managed 2 of these projects in accordance with the internal program guidance, including through contracts that specified expected outcomes.

One of the government-directed projects repurposed the program funds, and the project was never managed by the program team. However, it continued to be reported as part of the program. This created ambiguity about the program’s scope and results. Where funds are repurposed and no longer managed under the program, it is clearer if they are excluded from program reporting.

The department submitted a further 3 projects to government for approval due to the level of funding required. These projects applied through the competitive process, but the information prepared for the government was less comprehensive than for other projects. For example, one project did not have an investment case. This meant the documentation supporting government approval was inconsistent with that of other projects assessed through the competitive process. This can give rise to concerns about fairness, transparency, and consistency in the awarding of grant funding.

Recommendation 3 We recommend that the department strengthens the consistency of grant assessment decision-making by applying the same assessment procedures to all projects participating in the competitive process. |

Some unsuccessful applicants received advice about the outcome before the final endorsement

The department informed a number of unsuccessful applicants of the outcomes of their applications before the Investment Panel had formally endorsed the recommendations.

While this was intended to provide timely responses, notifying applicants only once decisions are formally endorsed would support procedural fairness and reduce the risk of miscommunication or conflicting advice.

Processing time frames improved after changes to approval processes

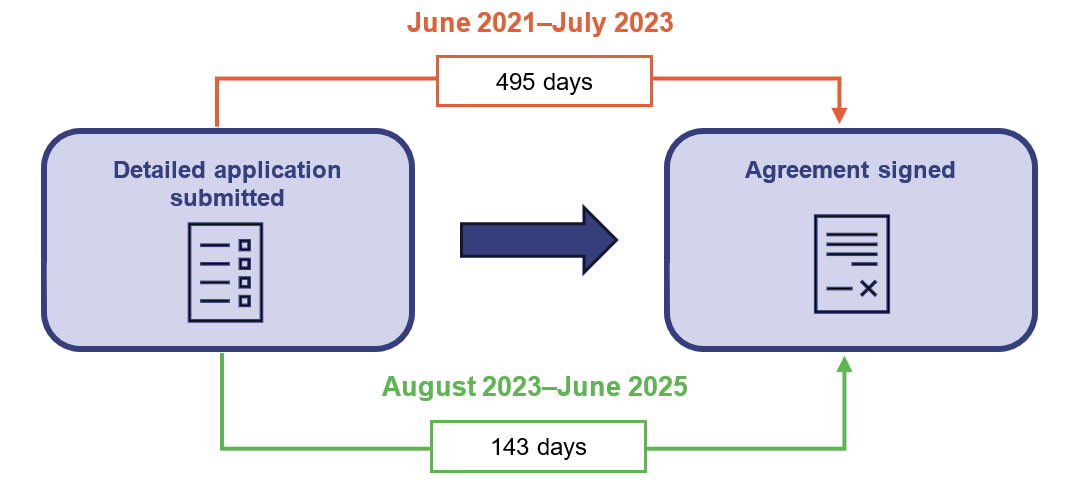

In the early stages of the program, assessing and approving applications took a long time. For projects submitted between June 2021 and July 2023, the average time from detailed application receipt to the signing of agreement was 495 days.

Delays were caused by the existence of multiple review layers and the need for financial approvals at senior levels. The department had no internal or public time frames for processing applications, making it harder to manage applicant expectations and monitor progress.

In mid-2023, the department made changes to reduce delays. These included engaging with applicants earlier to refine submissions and address issues before formal assessment and streamlining internal review processes. It later increased financial delegation thresholds, reducing the number of approvals requiring executive sign-off.

These changes significantly reduced processing times and improved the applicant experience. Figure 5E shows the average time frames before and after these changes.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office using data from the Department of State Development, Infrastructure and Planning.

Were funding agreements effective and appropriately balanced?

Effective grant agreements should aim to achieve value for money by managing financial risks and ensuring the funding achieves the intended outcomes. They should include clear terms and conditions, sound risk-sharing arrangements, and enough flexibility to support a range of businesses within the targeted industries.

The funding agreements supported accountability and met policy standards

The funding agreements reflected the Queensland Government’s grant and financial management frameworks. The department used standard templates that outlined payment milestones, performance conditions, and reporting obligations.

The department supported grant recipients to meet their agreements. It held initial meetings with recipients to clarify expectations, roles, and responsibilities, and provided formal letters outlining their obligations.

While some grantees found the reporting requirements onerous, they recognised the need for rigour when receiving public funding.

Agreement conditions strongly protected the state, which limited the ability of emerging businesses to apply

The agreements prioritised strong financial protection for the state. Most financial risk shifted to recipients through performance-based payments, reimbursement models, and the requirement for bank guarantees as security. While these conditions helped protect public funds, they limited flexibility, particularly for early-stage businesses or those with less financial capacity.

The lack of a defined risk appetite limited the flexibility of the program

Investing in emerging industries is inherently risky. The department did not define or document the level of risk it was willing to accept to achieve the program’s policy objectives.

In the absence of this, the program defaulted to applying standard financial safeguards, regardless of project type or context. This limited its ability to tailor conditions in ways that may have supported innovation while still managing risk.

Nine applicants withdrew from the program after receiving a funding offer. Of these, 4 cited performance requirements and rigid contract terms as their main concerns, saying the agreements imposed significant risks and were too onerous. The program's controls were designed to protect public funds but applying them uniformly limited flexibility. This may have inadvertently excluded viable projects that were consistent with the program’s intent.

Designing grant programs to balance accountability with flexibility requires a clear understanding of the risks that are acceptable in order to achieve policy goals. A more scaled approach – adjusting conditions based on project size, risk profile, and recipient capacity – could improve accessibility, while still ensuring accountability.

Recommendation 4 We recommend that all entities ensure their grant processes match the government’s desired outcomes, particularly in terms of which applicants can successfully apply. |

Commercial-in-confidence clauses make reporting to the public challenging

It can be challenging to ensure transparency over public spending while protecting the commercial interests of grant recipients. The Right to Information Act 2009 (the Act) requires entities to weigh the public interest in disclosure against any likely harm to business interests. However, the Act offers only limited guidance on how to manage commercial-in-confidence information in the context of grants.

The department included confidentiality clauses in its funding agreements to protect sensitive information and encourage private sector participation, particularly during the development and negotiation of projects. In practice though, these clauses restricted the department’s ability to publish information such as funding amounts and project details.

Older guidance, including the Public Accounts Committee’s 2002 report on Commercial-in-confidence arrangements, recognised that the sensitivity of information generally declines over time. It recommended that entities periodically review confidentiality provisions and establish clear time frames for disclosure once the need for secrecy has passed.

The Queensland Government has since published a Use and disclosure of confidentiality provisions in government contracts guide. It provides principles for identifying and justifying commercially sensitive information, and for considering whether such confidentiality is appropriate. While the guide is aimed at procurement contracts rather than grant agreements, entities could adapt its principles to improve transparency in grant programs.

Developing policies for reviewing confidentiality provisions, particularly after project delivery, would support greater transparency and accountability.

Recommendation 5 We recommend that all entities improve public transparency by reviewing commercial-in-confidence classifications and identifying information that can be published after a project is delivered. |

6. Measuring the impact of the program

All government programs need to demonstrate they are a good use of public funds. This includes monitoring whether funded projects are progressing as planned and whether programs are achieving their intended outcomes.

It also means using information on how programs have performed to improve delivery over time. When assessing the outcomes of a grant program, we look for the following elements:

- structured processes to track progress against grant agreements

- monitoring and evaluation that is planned from the start

- outcome data, such as the number of jobs created, collected as part of regular processes

- evidence that the program is having an impact.

In this chapter, we report on how well the Department of State Development, Infrastructure and Planning (the department) addressed these elements through its design and delivery of the Industry Partnership Program (the program).

How well does the department monitor the progress of projects?

Grant agreements usually set out specific milestones. These are key points in the project timeline that must be met before recipients can claim payments. Reaching these milestones helps show that their projects are progressing as expected.

The department’s process protects the government from financial risk

As mentioned in Chapter 5, the program uses a reimbursement model, meaning grantees only receive funds after they meet agreed requirements. If a grantee does not meet a milestone or provide the necessary evidence, no payment is made. This helps protect public funds by reducing the risk of paying for incomplete or non-compliant work.

For job creation data, verification includes checking payslips, payroll tax records, or information held by the Queensland Revenue Office. This ensures the program team receives timely and verified information before releasing funds.

The checks and evidence required are not adapted to suit the size and risks of each project

The level of evidence required to release funds should reflect the risk of fraud or non-compliance. As discussed in Chapter 4, these risks were not formally assessed at the start of the program. Without this foundation, the department could not tailor its acquittal processes – its checks and evidence requirements – at the program, project, or payment level.

As a result, the department applies the same evidence requirements and verification steps to all claims, regardless of risk. In some cases, this means grantees must submit large volumes of documentation for relatively small payments. This creates an unnecessary burden for the grantees providing the material and the staff reviewing it.

Recommendation 6 We recommend the department strengthens how it monitors whether grant recipients are meeting their obligations, with checks that match the risk level of each project. This includes conducting more frequent or detailed checks for high-risk projects and simpler checks for low-risk ones. |

Project non-compliance could be monitored more efficiently

When a grantee cannot meet a milestone, they need to request a variation to their grant agreement. In our sample testing, 7 out of 8 projects had reached their first milestone date. Of these, 4 missed at least one milestone without requesting a variation. Some delays extended beyond 3 months. In other cases, grantees requested multiple variations and still did not meet the revised date.

These issues suggest a pattern of milestone non-compliance. While the reimbursement model reduces financial risk, the frequency and length of delays highlight concerns about project delivery and point to weaknesses in how non-compliance is monitored and addressed.

The program did not provide clear internal guidance to staff on how to escalate the response to non-compliance, particularly in cases where repeated issues could affect delivery. This gap limited the department’s ability to respond consistently and proactively to emerging risks.

The program team stores relevant correspondence and approved variations in its records management system. This is not a grants management system but a general system for storing records.

The team also tracks project milestones using a spreadsheet, which does not support analysis of project-level trends or broader delivery risks. It also does not record reasons for variation requests, which means it misses the opportunity to identify common challenges across the program. Manual spreadsheets introduce greater risk of human error or fraud going undetected. A grants management system can help reduce this risk.

Recommendation 7 We recommend that the department uses an appropriate grants management system to support consistent delivery of grant programs, improve data capture, strengthen compliance monitoring, and enhance overall program transparency. |

How well does the department monitor program outcomes?

To decide whether grant programs should continue, change, or stop, departments need to understand whether they are working as intended. Those who demonstrate better practice set out how program success will be assessed, typically in a monitoring and evaluation framework or plan.

The department collects reliable data to estimate some project outcomes

The department grouped the program’s intended outcomes into 3 categories: business, supply chain, and ecosystem. Funding was designed to benefit grant recipients and their suppliers and broader industry. The assessment criteria and performance indicators the department documented in the program design reflected this intent. Figure 6A shows how the department categorised these outcomes.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office using information from the Department of State Development, Infrastructure and Planning.

The department built outcome reporting into agreements and milestone payments

The department translated some of the key outcome indicators into performance requirements for projects and embedded them in funding agreements. These indicators, used during due diligence and economic assessment, typically included:

- the number of jobs created within the grantee business and in other businesses due to the project

- investment in Queensland businesses.

This helped ensure that project-level outcomes could be measured and tracked.

To support this, the department requires grantees to provide outcome data when submitting payment claims. Each grantee is also required to submit an annual report. The report template asks grantees to describe the outcomes they have achieved in more detail, including any broader impacts not captured through milestone reporting. This provides additional context about project benefits beyond core contractual obligations.

Data on the impacts on the broader supply chain and ecosystem is less reliable

The department does not verify data provided in annual reports on supply chain and ecosystem impacts. Some grantees include numerical estimates to support their claims; others provide only qualitative descriptions, such as stating that their project helped local businesses work together or supported exports to other countries.

This limits the department’s ability to aggregate information and report on overall program impact. Instead, it relies on case studies to illustrate how projects contribute to broader industry outcomes. Without verification, the accuracy of the information in case studies cannot be assured.

There was a lack of clear planning for monitoring and evaluating the impact of the program

The department did not establish a comprehensive monitoring and evaluation framework at the start of the program. While some key elements were in place, the absence of a full framework left gaps in how the department tracked and assessed the impact of the program.

The department did not explain how outcomes would be achieved

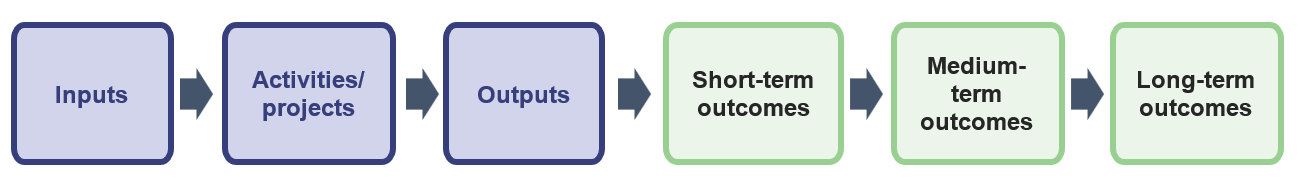

A key gap was the absence of program logic. Program logic models visually map how a program is expected to work – from inputs and activities to outputs and outcomes. This helps clarify how individual projects contribute to the program’s overall objectives. Figure 6B shows the typical elements of a program logic.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office.

Defining these outcomes early helps develop lead indicators – early signs that a program is progressing as planned. These indicators can show whether the program is likely to meet its long-term objectives without needing to wait for the full impacts to occur.

Some of the program’s intended outcomes, like job creation, are relatively straightforward to measure. Others, such as broader supply chain or ecosystem impacts, are more difficult to quantify or attribute directly to the program. The available information is often limited in volume, consistency, and reliability.

A program logic model would have helped address these challenges by clarifying how individual project outcomes contributed to the program’s overall objectives. Without it, the department has struggled to assess whether the program was on track to achieve its intended impact.

The department conducted reviews but did not report on them publicly

Although the department did not have a framework in place, it commissioned an external review in year 1 to provide quick, high-level feedback on early implementation. It also conducted an internal review in year 4. The department shared the findings of both reviews with internal stakeholders, including the Investment Working Group and Investment Panel. The reviews led to minor adjustments to the program. However, in the absence of performance targets for the program, such as the number of jobs it intended to create, these reviews could not conclude as to whether the program was on-track.

The department did not publish the review findings. Publicly sharing evaluation outcomes is an important part of program accountability. The department’s only public reporting on outcomes was through its annual Service Delivery Statement measures at the time of the budget. These combined the program’s results with those of other initiatives, limiting transparency over the program’s individual performance.

The department needs improved economic analysis to better assess the impact of the program

Grantee reporting alone is not enough to estimate the program’s full economic impact. While grantees can report on direct outcomes, such as the number of people they hired, they are less able to reliably estimate indirect outcomes, such as jobs created in other businesses through their spending. Current reporting templates ask grantees to estimate these broader impacts. See Figure 6D for examples of self-reported outcomes from grantees.

Rather than requiring them to make these assumptions, the department could use more reliable data, such as grantees’ actual supply chain expenditure, as an input to model broader economic impacts. It could consider re-running the initial economic models it used during the assessment of applications, using updated data, once projects are underway. This would improve the accuracy and credibility of its assessment of the impact of the program.

The department would benefit from obtaining economic evaluations at key points in the program lifecycle. This would provide a more objective assessment of economic outcomes and strengthen the evidence base for future decisions.

Recommendation 8 We recommend that the department strengthens how it evaluates programs and measures impact by:

|

What impact has the program had?

The department reported that as at 31 July 2025, of the 30 projects funded by the program, 12 are in pre-construction, 8 are in construction, and 10 are operational.

Many of the program outcomes are linked to projects becoming operational. As a result, some of the outcomes reported in this section are projections rather than results achieved to date. These projections are based on the department’s reporting, and we have not audited them.

The program is expected to generate economic activity in Queensland

The program is forecast to deliver economic benefits through private sector and co-investment alongside government funding. Figure 6C shows the economic activity that the program is expected to generate in Queensland.

Note: *The total investment figure excludes program funding provided through the Industry Partnership Program. It reflects private sector and other co-investment (e.g. federal contributions) generated through the program.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office using data from the Department of State Development, Infrastructure and Planning.

These projected outcomes are consistent with the program’s objectives. For every one dollar of program funding committed, the program is expected to generate 5.60 dollars of investment in Queensland. The program required grantees to contribute at least 50 per cent of project costs. In many cases, the department negotiated lower funding contributions from government than was initially requested by applicants.

This private investment contributes to local job creation within grantee businesses. It also supports economic growth more broadly, as supply chain spending creates flow-on activity across multiple sectors.

Grantees have reported supply chain and ecosystem outcomes

Grantees have reported a range of positive industry outcomes, as summarised in Figure 6D. This information comes from their annual reports and has not been verified by the department.

The outcomes vary across projects and are often difficult to report consistently. This makes it challenging to assess program-wide impact. However, the snapshot below provides useful qualitative insights into the supply chain and ecosystem benefits reported by grantees.

Supply chain strengthening and local economic development | Environmental sustainability and decarbonisation |

|

Strengthened regional and local supply chains, increased local procurement and investment in shared infrastructure, enhanced resilience and economic diversification. |

Use of renewable energy, eco-friendly building design, emission reduction, recycling innovation, and contribution to low-carbon sectors like batteries. |

Job creation, upskilling and workforce transformation | Ecosystem and industry diversification |

|

Direct job creation, apprenticeships, training programs, and development of new technical skill sets tailored to advanced manufacturing and technology industries. |

Transition from traditional to future-facing industries, fostering innovation hubs and co-location, seeding new sectors in regional areas, and strengthening our own capabilities. |

Technological transformation and industry modernisation | Export growth and global market access |

|

Implementation of cutting-edge technology that improves productivity, enables new product development, and positions Queensland as a leader in high-tech industries. |

Enabling Queensland-made innovations to access international markets through export services and global-ready facilities. |

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office using information from the Department of State Development, Infrastructure and Planning.

The broad scope of the program made it difficult to focus on individual industries

The program was intended to support industry development across a broad range of sectors and regions. It ultimately funded projects across 10 industries.

While the intent to maintain flexible funding is understandable, having broad eligibility reduced the likelihood of achieving meaningful impact in any single industry. Future grant programs may benefit from striking a better balance between flexibility and targeted investment.

A more strategic approach could allow projects to build on each other’s success and generate greater cumulative impact within each priority industry.