How do you apply AASB 16 to lease rentals that change due to CPI changes?

We give an overview of the new accounting standard AASB 16 Leases in a related article. In that overview, we describe the effect of putting operating leases on balance sheets. We also describe the financing effect and how your profit or operating result will change from lease accounting, even if your underlying operations stay the same.

We highlight that because the accounting under the new standard appears similar to that used for finance leases, people may have a false sense of security. For finance leases, rentals are generally fixed. For operating leases, rentals often change, for example, due to changes in the consumer price index (CPI) or other index changes. Accounting for these changes involves numerous complexities.

At a high level, under the new standard you initially recognise a lease liability at the discounted amount of projected cash flows (lease rentals) for the lease term. You also recognise a corresponding lease asset.

So how do you apply this to lease rentals that change due to CPI changes? For simplicity, we ignore caps and floors (for example, a minimum increase of 3 per cent, or a maximum increase of 5 per cent). For example, assume you have a lease that started on 1 July 2015 for 10 years that has an annual rent of $1,000,000 paid monthly in advance, and rentals change on 1 July due to changes in the CPI index for the previous 30 June. We have assumed a 5 per cent discount rate.

One difficulty of accounting for CPI increases is that there are different CPIs – a national index (weighted average of the 8 capital cities), as well as indices for the capital cities. Let us assume that the lease rentals are based on the Brisbane index.

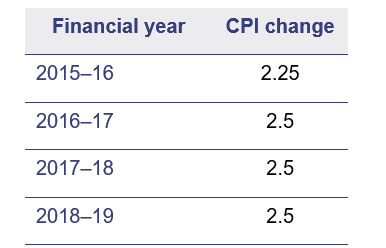

At 1 July 2015, the information available for forecasts/projections of future inflation (CPI changes) included in the 2015–16 Queensland Budget was:

So, what lease rentals would you include in your projected cash flows to calculate your lease liability? Would you pay to prepare a report projecting CPI increases for years 5–10, would you continue using 2.5 per cent, or would you use another estimate?

Another difficulty is that actual CPI is rarely what is forecast. For example, at 30 June 2015, the Brisbane CPI was 107.4 [Source: ABS Consumer Price Index, Australia, June 2016 (cat. no 6401.0)]. The June 2016 CPI was published on 27 July 2016, and the Brisbane index was 109.0 – an increase of 1.5 per cent.

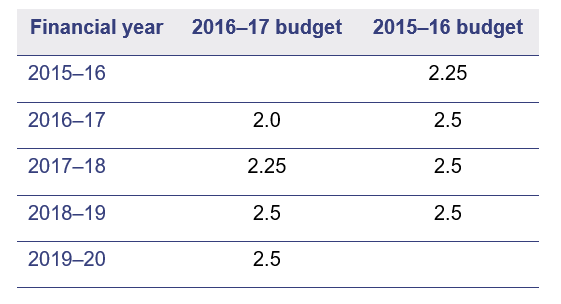

At 30 June 2016, the 2016–17 Queensland Budget had been published and included forecasts/projections of:

At 30 June 2016:

- What would you have included in your projected cash flows to calculate your lease liability?

- How would you have dealt with the change between forecast and actual CPI in 2015–16 (2.25 per cent versus 1.5 per cent), and the change in forecasts in 2016–17 from 2.5 per cent to 2 per cent, and 2017–18 from 2.5 per cent to 2.25 per cent?

- When would you have recognised these changes? Would you have used the June 2016 CPI figures (that were published in July 2016) as post-balance information as at 30 June 2016?

Similar issues and differences arise for 30 June 2017 and 30 June 2018.

Does the above seem extraordinarily complex? The International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) acknowledged this and included provisions to simplify the accounting for CPI changes. However, while simplified, they are not simple. The provisions are different to usual asset accounting and are likely to involve changed or new computer systems.

The main provision for CPI and other index changes is that they are recognised when the cash flows change. You do not include forecast future CPI changes in your projected cash flows, and consequently, there is no need for true-ups and re-estimations.

For example, for the above lease, lease rentals change as at 1 July, and that is when you recognise the changes in lease rentals in your lease liability. You do not make adjustments as at 30 June, even if you know by the time you approve your financial statements what the changes will be.

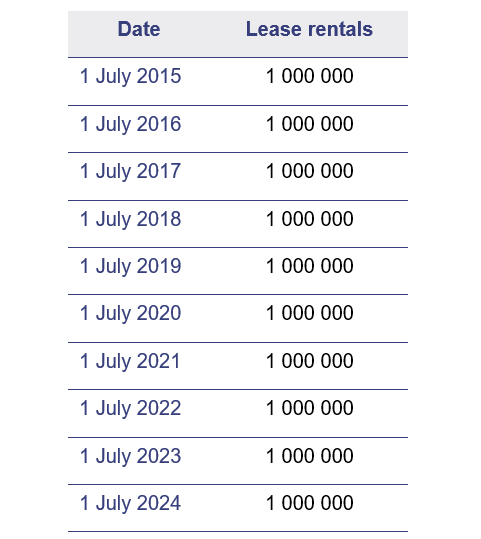

So, at 1 July 2015, the lease rentals included in the lease liability calculation are:

At 1 July 2015, the lease liability would be recognised at $7,848,186, using the 5 per cent discount rate (adjusted for monthly payments).

At 30 June 2016, the lease liability will have increased by $382,928 through accrued interest, and decreased by the lease rentals of $1,000,000, resulting in a liability of $7,231,114. The lease liability reconciles to the discounted amount of the future 9 additional lease payments of $1,000,000.

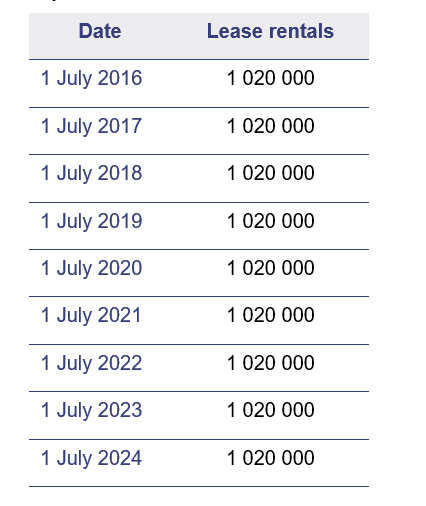

On 1 July 2016, the lease rentals increase by CPI. Assume a 2 per cent CPI increase. The lease rentals included in the lease liability would be:

At 1 July 2016, the lease liability would need to be recognised at $7,375,737.

As you can see, the lease liability needs to increase from $7,231,114 to $7,375,737, an amount of $144,623. The corresponding entry is to increase lease assets by the same $144,623. Depreciation is then calculated on the higher leased asset amount.

As we noted above, while the calculations have been simplified, they are not simple. On a practical basis, do you know which CPI your lease rentals change by, and do you know when your lease rentals change? Do they all change 1 July, do some change 1 January, or do they change on the lease anniversary, which could be sometime during the year? If you have more than a few leases, this might mean adjustments to lease liabilities and lease assets each month or every few months. Are your computer systems capable of processing calculations? Are you ready for these changes?