Overview

Demand for ambulance transport and emergency departments continues to grow faster than the population. This demand, and more people presenting with complex issues, is placing increasing pressure on Queensland's ambulance service and emergency departments.

Tabled 14 September 2021.

Auditor-General’s foreword

Across the globe, COVID-19 demonstrated the need for efficient and effective ambulance services and emergency departments as many organisations planned for and responded to the crisis. This audit topic was—and continues to be—an important matter for Queensland.

In 2020, during the worst of the pandemic, I temporarily paused this audit in support of the Queensland health entities that were preparing for a potentially large influx of COVID-19 patients. We aimed to be realistic and flexible with our audit requirements to ensure we were auditing the right matters at the right time, so that our insights remain pertinent and practicable.

The vital need for preparedness as the pandemic hit, but a lesser number of COVID-19 patients than anticipated, gave health entities the opportunity to focus on improving patient flow through hospitals. However, more work needs to be done, with our emergency departments and the Queensland Ambulance Service providing critical care to more people every year. In 2019–20, there were over 1.6 million presentations to public hospital emergency departments, over a third of which arrived by ambulance.

Many issues contribute to the performance of emergency departments, in particular funding, staffing, and the availability of emergency and inpatient beds. There has also been recent attention to the challenges surrounding ambulance ramping at hospitals. All of these issues are frequently topical and concerning, but they are outside the scope of this report. This report follows on from our previous 2015 audit that focused on the performance of emergency departments against specific targets. These other issues may be the subject of future audits, and I have included a topic on delivering ambulance services in my Forward work plan 2021–24.

In Planning for sustainable health services (Report 16: 2020–21), tabled in parliament on 25 March 2021, I highlighted the need for whole-of-service planning that uses up-to-date data and involves key stakeholders. There are similar themes in this report. It is important that emergency departments and the Queensland Ambulance Service have accurate, readily available, time-based performance measures. This will help them identify performance issues so they can work with and across other clinical areas to address the causes of delays. We provide five recommendations in this report that will help them achieve this.

Brendan Worrall

Auditor-General

Report on a page

This audit follows on from Emergency department performance reporting (Report 3: 2014–15). It assesses whether Queensland Health:

- is effectively managing performance in terms of emergency length of stay (ELOS—the amount of time people spend in emergency departments (EDs) before being admitted or discharged) and patient off stretcher time (POST—the amount of time it takes to transfer people from the care of ambulance staff to the care of emergency departments)

- has implemented all the recommendations we made in Report 3: 2014–15 concerning the reliability of the data being reported.

Increasing demand is putting pressure on EDs

The Department of Health—which includes the Queensland Ambulance Service (QAS)—and hospital and health services (collectively referred to as Queensland Health) are working together to improve emergency department (ED) patient wait time. However, more people are arriving at EDs for treatment, and these presentations are becoming more complex. This has put pressure on Queensland Health’s ability to improve ELOS and POST performance.

While each year EDs continue to treat more patients within required time frames, their performance against these two measures has gradually declined and they are consistently unable to meet their targets.

Decision-makers need more accurate and timely information

Operational entities within Queensland Health are working together to improve ED performance. There have been a range of strategies implemented to help improve patient flows; however, the overall performance of the system has not improved. Furthermore, Queensland Health has identified that strategies are not consistently evaluated and understood to ensure the effective rollout across the state.

Despite the Queensland Ambulance Service becoming part of Queensland Health from 1 October 2013, there is a lack of system integration with integrated electronic medical record (iEMR) modules in hospitals. This limits Queensland Health from being more successful in improving performance and identifying root cause issues in the short term.

In Report 3: 2014–15 we concluded that ‘controls over ED performance data have been and remain, weak or absent’. In 2021, controls still must be improved to ensure QAS and ED data is complete, accurate, and validated in a timely manner. Queensland Health does not currently have an adequate and efficient approach for detecting and correcting data errors relating to a patient’s length of stay and time taken to be moved off an ambulance stretcher.

Progress towards our previous recommendations

Queensland Health has implemented two of the four recommendations we made in Report 3: 2014–15. It has not effectively addressed the risk of inappropriate use of short-term treatment areas and has not identified how to detect unauthorised data entries and changes.

Our recommendations

We have made five recommendations to help Queensland Health improve its processes for data reliability, ED performance measures, the appropriate use of ED short-term treatment areas, and the interface between ED and QAS systems.

1. Recommendations

We recommend that the Department of Health (including the Queensland Ambulance Service (QAS), and hospital and health services (HHSs)):

|

Data reliability |

|

|

Performance measures |

|

|

Short-term treatment areas |

|

Reference to comments

In accordance with s. 64 of the Auditor-General Act 2009, we provided a copy of this report to relevant entities. In reaching our conclusions, we considered their views and represented them to the extent we deemed relevant and warranted. Any formal responses from the entities are at Appendix A.

2. Recognising demand on emergency departments and their performance

This chapter is about how well the Department of Health—which includes the Queensland Ambulance Service—and the hospital and health services (collectively referred to as Queensland Health) are working together to manage emergency department performance.

Has emergency department performance improved since our audit in 2014–15?

Demand for emergency departments (EDs) is growing at a faster rate than population growth, and more people are arriving (presenting) at EDs with complex issues. The EDs have been treating more people within recommended time frames each year. However, as a percentage of the entire patient population, their performance has been declining.

The overall emergency length of stay (ELOS—the length of time people stay in EDs) target is to complete treatment within four hours for 80 per cent of patients. The patient off stretcher time (POST—the amount of time it takes to transfer patients off ambulance stretchers, with a completed clinical handover, to EDs) target is to transfer 90 per cent of patients within 30 minutes.

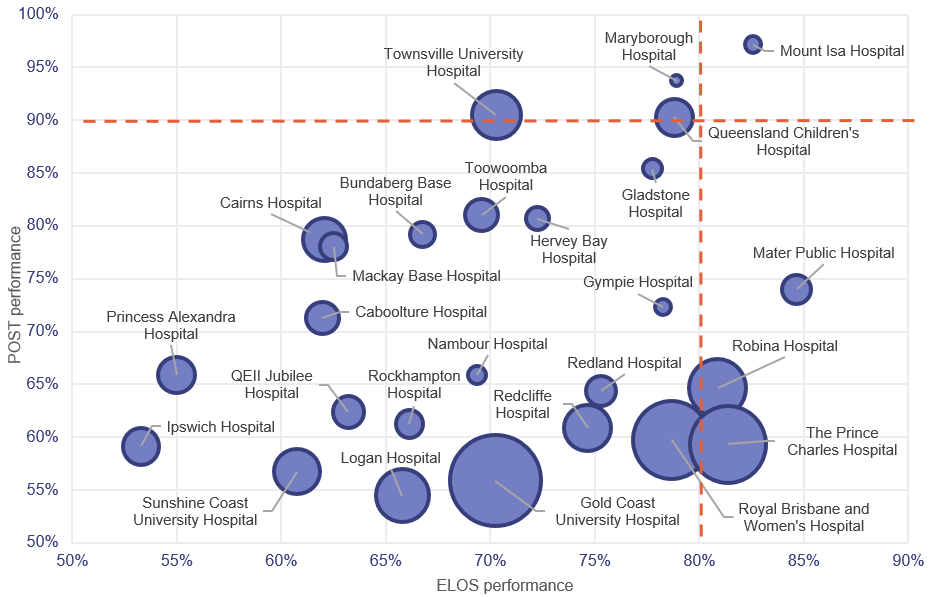

Figure 2A shows that during the period from July 2020 to February 2021, only one of the top 26 reporting hospitals met the targets for both ELOS and POST. All of Queensland’s top 26 reporting hospitals are listed in Appendix F.

Notes:

- The size of the circles corresponds to the number of presentations and includes COVID-19 fever clinic activity. The orange lines represent the ELOS and POST targets.

- Queensland’s top 26 reporting hospitals are listed in Appendix F.

- Despite some volatility at individual hospitals, performance outcomes were materially the same for the prior year, which was impacted by the full COVID-19 lockdown. Figure 2A also includes some volatility at individual hospitals over shorter targeted lockdowns to deal with localised COVID-19 outbreaks.

- The Mater Adult Public Hospital (Mater Public) is jointly funded by Queensland Health grants and revenue generated by Mater Private Hospitals. It is one of Queensland Heath’s public reporting hospitals.

Queensland Audit Office from emergency department data collection and POST data for the top 26 reporting hospitals.

Reporting hospitals—Queensland Health publicly reports on the performance of its hospitals. Not all hospitals provide 24/7 emergency care.

The current public ED performance reporting covers the hospitals in Queensland that have:

- purposely designed and equipped areas for assessment, treatment, and resuscitation

- the ability to provide resuscitation, stabilisation, and initial management of all emergencies

- availability of medical staff in the hospital 24 hours a day

- designated emergency department nursing staff 24 hours per day, seven days per week, and a designated emergency department nursing unit manager.

This report includes the top 26 hospitals that treat approximately 77 per cent of Queensland’s emergency department presentations and are the ‘reporting hospitals’ referred to in this report. It aligns with the hospitals we reported on in our 2014–15 audit.

There have been significant increases in demand and in the number of complex cases

In response to recommendation 4 in Emergency department performance reporting (Report 3: 2014–15) Queensland Health implemented separate evidenced-based performance targets for the patients it admits and those it discharges. Admitted patients usually require more complex care, and their ELOS relies on the availability of beds in the hospital (inpatient beds). For this reason, a 60 per cent target is set for admitted ELOS, compared to 90 per cent for discharged patients.

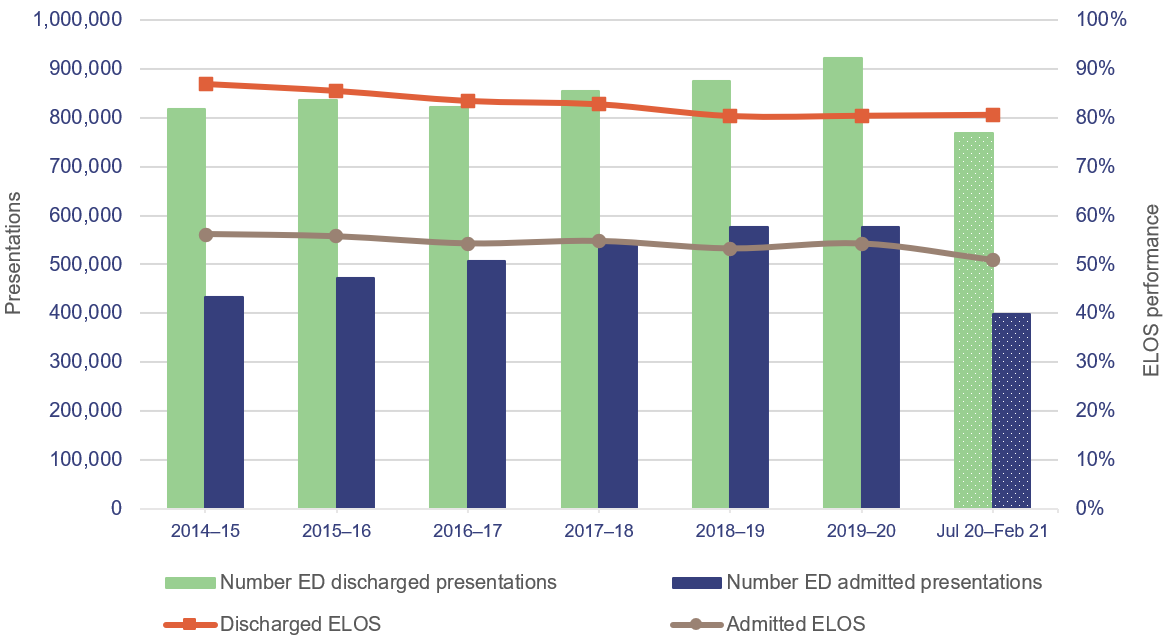

Figure 2B compares the increase in presentations for patients who are admitted and discharged to performance against the ELOS target from 1 July 2014 to 28 February 2021.

It shows that statewide ELOS performance for admitted and discharged patients has gradually declined, while the number of presentations has increased. The performance for discharged patients has declined at a greater rate compared to admitted patients. However, the growth in admitted patients has been at a faster rate than discharged patients.

Notes: Excludes deaths in the ED, patients who did not wait, patients who left at own risk, and transfers to another hospital. Includes COVID-19 fever clinic activity. 2014–15 to 2019–20 are full financial years; July 2020 to February 2021 is a partial year.

Queensland Audit Office from emergency department data collection for the top 26 reporting hospitals.

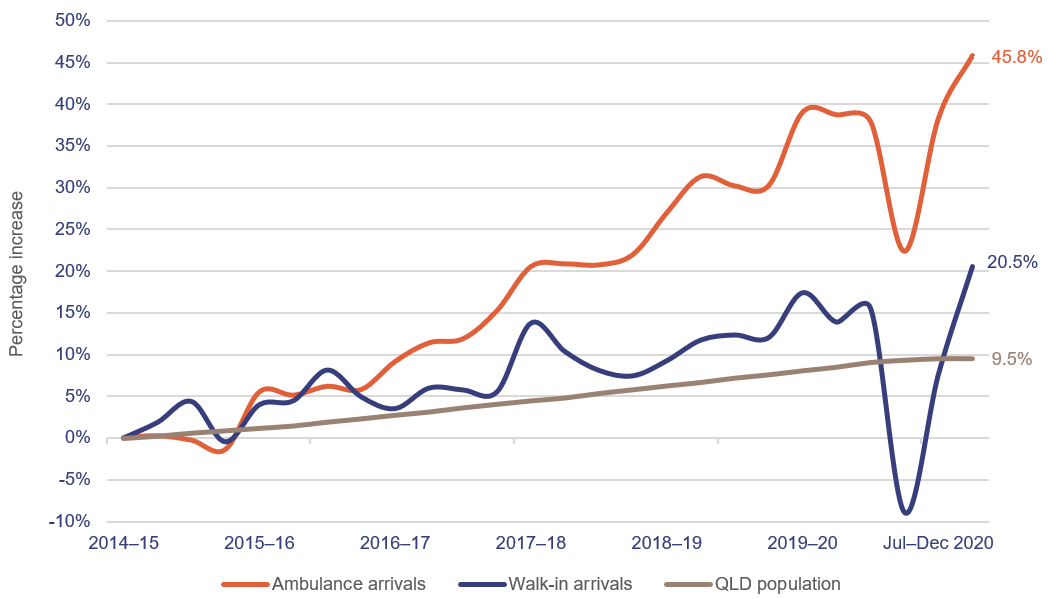

Demand for service has outpaced population growth

As shown in Figure 2C, between July–September 2014 and October–December 2020, ‘walk‑in’ ED presentations (people who do not arrive by ambulance) increased by 20.5 per cent, and ambulance arrivals to EDs increased by 45.8 per cent. Population growth over the same period was 9.5 per cent.

Notes: The most up-to-date population data available was the September 2020 quarter. QLD—Queensland. Excludes COVID-19 fever clinic activity.

Queensland Audit Office from emergency department data collection for the top 26 reporting hospitals and quarterly Australian Bureau of Statistics population data.

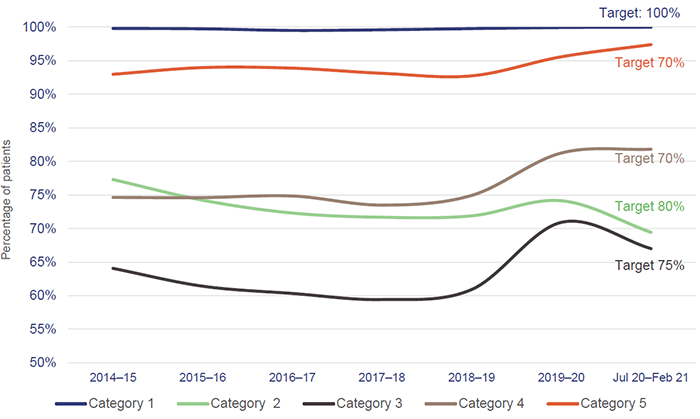

Patients seen within the clinically recommended time

Queensland Health measures how soon an ED patient is seen by a treating doctor or nurse upon their arrival at the ED, triaging patients according to a national framework in categories of 1 (immediately life-threatening) to 5 (less urgent).

Figure 2D shows that since 2014–15, Queensland Health has consistently outperformed its targets for categories 4 and 5, and mostly hit its target for category 1. However, it has not met its targets for categories 2 or 3.

Notes: Includes COVID-19 fever clinic activity. Category 1—immediately life-threatening (treatment within two minutes). Category 2—imminently life-threatening, or important time-critical treatment, or very severe pain (treatment within 10 minutes). Category 3—potentially life-threatening, or situational urgency (treatment within 30 minutes). Category 4—potentially serious, or situational urgency (treatment within 60 minutes). Category 5—less urgent (treatment within 120 minutes).

Queensland Audit Office from emergency department data collection for the top 26 reporting hospitals.

Patient off stretcher time performance

Queensland’s target for POST is to have 90 per cent of patients transferred off stretchers into the care of the ED within 30 minutes. This target has not been met at the statewide level in the past seven years.

The overall POST performance for the top 26 reporting hospitals has steadily decreased from 85.9 per cent in 2014–15 to 68.5 per cent for the period July 2020–February 2021. Our Forward work plan 2021–24 includes a proposed audit on delivering ambulance services that may address the root causes contributing to this decline in performance.

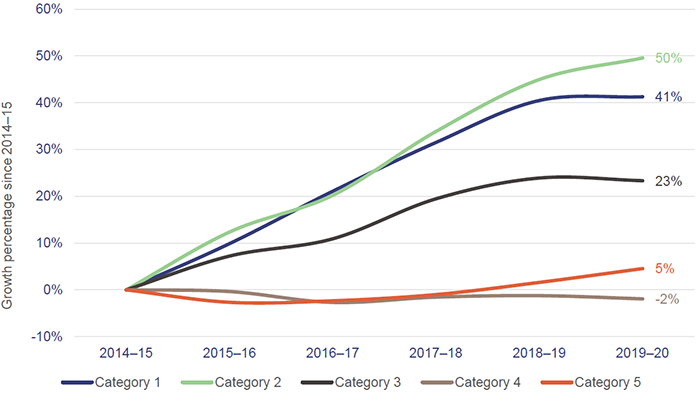

The number of complex presentations has increased

ED presentations have become more complex. Figure 2E shows that since 2014–15 category 1 presentations (immediately life-threatening) has grown by 41 per cent and category 2 presentations (imminently life-threatening or important time-critical treatment, or very severe pain) by 50 per cent. Categories 1 and 2 are often significantly more resource intensive to treat in emergency departments than categories 3 to 5. The slowdown in growth in 2019–20 is partly attributable to statewide and localised lockdowns.

Note: Excludes COVID-19 fever clinic activity.

Queensland Audit Office from emergency department data collection for the top 26 reporting hospitals.

Are Queensland Health entities effectively monitoring emergency department performance?

ELOS and POST are both time-based measures; they do not assess quality of patient care or patient outcomes directly. They do provide an indication of some elements of ED performance, but they are summary measures for a complex health system, and they have limitations.

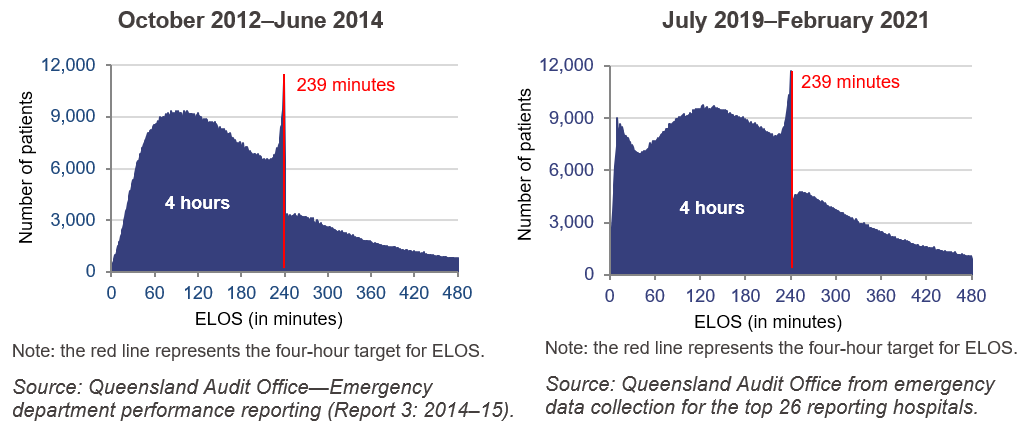

The pattern of target-based emergency care has not changed

In our 2014–15 audit, we observed a pattern of EDs seeming to meet targets, but not being able to support their ELOS times with clear patient records. The departure of patients from EDs spiked just before the patient stays reached the four-hour (or 240 minute) target. One of the reasons given by clinicians was that they were working to time-based care, where patients are either discharged, admitted to a ward or admitted to a short-stay treatment area before the four-hour target. This trend has continued since our previous audit, as shown in Figure 2F.

Contributing factors to ED performance outcomes

How quickly EDs can receive and treat patients depends on a variety of factors, including the available emergency and inpatient beds, ED staffing, and inpatient ward staffing. Any block to accessing inpatient wards will significantly impact on an ED’s ability to meet performance targets.

Queensland Health does not consistently publicly report on these factors, safety measures or on other key issues affecting patient flow, such as adequacy and affordability of primary care in the community, increasing demand for ambulance services, or a lack of inpatient bed capacity.

The wait time between ambulance arrival and triage is not monitored

To determine the root cause of any time-based performance issue, it can be useful to break the total time into its separate components. This helps in identifying where delays occur and in targeting improvement activities.

A 2012 Queensland Health report on ED access identified that time between ambulance arrival and triage (time to triage) is a critical component in measuring off-stretcher performance. As a result, a previous Queensland Health protocol included a five-minute target for time to triage.

Queensland Health removed this target in December 2019 due to the ways in which arrival and triage times are recorded. Despite Queensland Ambulance Service (QAS) becoming part of Queensland Health on 1 October 2013, ambulance arrival time and ED triage time are captured in two different systems that do not talk to each other—an ambulance system and a hospital system. EDs capture triage time but not patient arrival time at the ED. QAS captures ambulance arrival time, but it does not always have the complete patient identity data required for the arrival time to be linked to the ED triage time.

As a result, Queensland Health is unable to assess whether there are any delays in commencing the triage process for ambulance arrivals and any impact on the off-stretcher time.

Performance of short-term treatment areas is not monitored and measured

Our 2014–15 report identified the risk of using short stay units inappropriately to reduce ED wait times (in order to achieve performance targets). The department has development guidelines to address this risk but not all hospitals have effectively implemented them.

Since 2014–15, several Queensland public hospitals have introduced initiatives similar to short stay units within EDs. For example, one hospital has a pre-discharge area within its ED for patients who require ongoing care (for example, for medications to be administered, ongoing observation, or further imaging or scans). Others have clinical decision units where patients are placed either while they wait for test results or short-term treatment to manage symptoms. In this report, they are collectively referred to as short-term treatment areas.

Admission to short-term treatment areas stops the clock for ELOS, meaning the time spent in these areas is not counted for ELOS purposes.

Hospitals recording data in FirstNet (a module of Queensland Health’s integrated electronic medical record) do not submit their short-term treatment data to the Department of Health (the department) because this data is captured as part of the inpatient journey outside of FirstNet. The department is currently not measuring and monitoring the length of stay in short-term treatment areas for those EDs that use FirstNet.

The department does not receive data from EDs to analyse how short-term treatment areas are used to manage patients, and how long patients remain within them.

In March 2021, Queensland Health commenced an ED Admission Interface Project to examine the use of admission units from the ED, such as clinical decision units and mental health units.

Are Queensland Health entities working effectively together to manage performance?

During our site visits in August and September 2019, we observed coordination and collaboration between QAS, hospital and health services (HHSs), and the department. This included regular meetings at the state, HHS and individual hospital levels; consultations when developing operational procedures and protocols; and joint decision-making to address daily operational issues.

The responsibility for overseeing QAS transferred from the then Department of Community Safety to the Department of Health on 1 October 2013. This followed structural reforms designed to ensure a more integrated and effective health system. QAS formally and informally communicates improvement opportunities at the HHS and whole-of-system levels—this includes communication channels such as the Patient Access Advisory Committee and the Emergency Services Management Committee. However, real-time (instant) patient data is not being shared between QAS and hospitals’ patient files, and from hospitals to QAS.

The Queensland Ambulance Service is sharing real-time data with selected hospital and health services

While ED and QAS data is recorded in different systems, QAS provides some real-time information sharing with hospitals, using ambulance arrivals dashboards, which are generally located at hospital triage areas. These dashboards provide hospitals with information about ambulance-related triple zero calls, patients being transferred from other facilities or general practitioner (GP) clinics, and ambulances on the way to hospital, and gives details on how long ambulances have been at the hospital. This helps ED staff plan over the immediate term. The dashboards are part of the patient access coordination hubs; these are discussed further in Case study 1 (Figure 2G) below.

Queensland Health has advised it will be expanding the use of dashboards and patient access coordination hubs across the state by the end of 2021.

In our planned audit on delivering ambulance services, for tabling in 2022–23, we will likely delve further into the extent of integration of ambulance and health services.

Patient records are manually shared

Paramedics use iPads to record detailed treatment and transportation information for each patient they attend. The iPads are not linked into the digital hospital system through the integrated electronic medical record.

In the absence of a real-time system interface, QAS paramedics print out digital ambulance report forms and provide hard copies to EDs. This is not an efficient use of time but is a critical process for sharing information. In instances where ambulances are dispatched urgently to the next incident, paramedics are expected to hand over their paper forms at the next available opportunity, which may not be until the next shift.

Queensland Health has asserted that the risk of key patient condition and treatment information not being communicated to ED staff is partially mitigated by paramedics providing treatment information verbally to hospitals at triage and handover.

System interface project

In February 2019, Queensland Health began a system interface project to improve patient handover at EDs through enhanced data sharing and integration. This included the dashboards at patient access coordination hubs.

It put the project on hold in April 2020 to focus on the COVID-19 planning and response effort.

At the time when the project was put on hold, Queensland Health had been trialling a pilot digital solution called the Digital Ambulance Report Application at the Princess Alexandra Hospital. This solution aims to enable the sharing of QAS patient data with EDs, specifically the electronic ambulance report form. The project was put on hold as part of the Queensland Government’s debt and savings plan. Because of the pause, Queensland Health has not compiled any findings from the trial.

The Queensland Ambulance Service only provides summary reports to key teams

QAS currently only provides a summary POST report to other relevant teams within the department. This contains information on the total number of patients transported and the number and percentage of patients transferred in under 30 minutes for each hospital and HHS.

HHSs do not receive aggregated patient-level data from QAS. This limits the HHSs’ ability to understand performance data and develop improvement plans.

Despite this, several HHSs are working on improvements. As an example, the Gold Coast HHS has been trialling a way to link ED and QAS data to identify specific issues with ambulance wait times.

Initiatives to improve emergency department performance

The department plays a key coordinating and oversight role of many improvement initiatives in the emergency department setting. HHSs may also proactively trial initiatives and report their findings and the outcomes to the department, recommending a wider roll out.

At each of the three hospitals we visited, we observed initiatives to improve patient flow through the ED. Case study 1 (Figure 2G) provides examples.

|

Initiatives to improve ED performance |

|

Patient access coordination hubs Seven HHSs have established a patient access coordination hub (PACH). These aim to improve patient flow through better collaboration between QAS and the HHSs. The PACH model uses real-time data including emergency capacity, ambulance operations, hospital-wide bed availability and scheduled inpatient stays. The department coordinated a review of the Metro South HHS PACH and identified that the PACH should evolve to focus on improving overall patient flow through the hospital, rather than focusing on managing rapid patient transfer from QAS to the ED. Queensland Health has been promoting the uptake of a new dashboard for the PACH at selected hospitals. This dashboard provides a range of measures regarding time at ED, hospital occupancy, and status of inter-hospital transfers. On 11 May 2021, the government announced the expansion of PACHs to an additional five HHSs by 30 June 2021, and the remaining HHSs will be included by 31 December 2021. Rapid transfers or Transfer Initiative Nurse model Metro South HHS, Gold Coast HHS and West Moreton HHS have processes in place at their main hospitals for the rapid transfer of patients from QAS to EDs. The processes involve the PACH and/or clinical staff identifying the most appropriate patient for priority transfer in response to high QAS demand in the community. Metro South HHS introduced a new role—a transfer initiative nurse—who aims to support the rapid transfer process by accepting handover of patients from QAS when no ED treatment spaces are immediately available after triage. A transfer of care procedure outlines the QAS’s and HHS’s responsibilities and identifies an escalation process through to ED doctors and nurses and the Metro South PACH. On 11 May 2021, the government announced this model would be expanded to Metro North HHS’s and Sunshine Coast HHS’s main hospitals and will add additional capacity to their existing models. The selection of hospitals was made based on demand, ELOS and POST performance, and availability of space to establish the model. Nursing autonomy trifecta trial Logan Hospital has implemented a nursing autonomy trifecta trial, which involves training and authorising nurses to initiate pathology, medication, and x-rays. The initiative is designed to start tests and/or treatment earlier for patients to reduce the patient’s length of stay. For example, if a patient requires an x-ray and the process takes two hours to complete, initiating the x-ray earlier should reduce the patient’s time in the ED. This initiative had the greatest effect on patients waiting for acute care. For these patients, average ED stay decreased from six hours and 20 minutes in January 2018 to just under four hours in February 2019 during the trial period. FRAIL initiative The FRAIL initiative at Townsville Hospital aimed to improve patient flow for the elderly. It involved having a dedicated nurse for elderly patients in the ED. Townsville Hospital found that elderly patients assisted as part of the initiative had an average ED stay of 4.8 hours, while those who were not assisted under the initiative had an average ED stay of 5.3 hours. Reviewed patients also had a lower rate of coming back (re-presenting) to the ED for the same condition within a short period of time, and a shorter length of stay for those who were admitted. Funding has been provided to continue and expand the FRAIL initiative to additional EDs. |

Queensland Audit Office from information provided by Queensland Health.

Initiatives are not always evaluated

While Case study 1 (Figure 2G) provides some examples where the HHSs and the department have evaluated improvement initiatives to assess their effectiveness, they have not always done so. For example, hospitals we visited were not always able to provide evidence that they evaluated their initiatives, for example the use of short-term treatment areas within EDs. In other cases, the evaluations of strategies trialled have not always been able to identify the key learnings that would lead to improvement in the overall performance of the system as a whole.

Queensland Health has a lack of guidance on how to develop and assess the success of these types of initiatives. Analysing direct cause and effect correlation between improvement activities and outcomes can be difficult due to the complex nature of patient flows, and the nature and growth of emergency activity statewide. These reasons limit its ability to define what success would look like for each initiative.

Despite the difficulties, it remains critical for HHSs and the department to be able to evaluate the initiatives and measure the effectiveness of changes in the EDs. This would allow key learnings to be captured and successful programs to be quickly rolled out to other EDs.

This is particularly important when hospitals have implemented several initiatives in a short time. Logan Hospital acknowledged this in its analysis of nurse-initiated pathology (the nursing autonomy trifecta trial), noting that it was difficult to determine if an improvement in performance could be attributed to the success of a single initiative.

3. Improving data reliability

Queensland’s public emergency departments (EDs) are gradually transitioning to FirstNet, a module of Queensland Health’s integrated electronic medical record. Currently, half of the 26 reporting hospitals' EDs use FirstNet. Our Report 10: 2018‒19 Digitising public hospitals found that the hospitals we audited were not experiencing the emergency department performance benefits expected from implementing the digital hospital suite of modules.

We assessed whether performance data on the proportion of patients admitted or discharged from EDs within the four-hour target time is accurately recorded and reported in FirstNet.

In doing so, we examined how ED performance data is:

- recorded, calculated, and checked

- reported within Queensland Health and to the public.

Having effective checks and processes (controls) in place helps prevent human error and assists in delivering accurate and reliable recording of data. At the hospital level, accurate and reliable data assists managers to identify root causes of poor performance and develop solutions.

Our findings from our 2014‒15 audit found a lack of controls around data reliability in the previous emergency department information system. We have found similar issues in FirstNet.

Is emergency department four-hour performance data accurate and verifiable?

We found the accuracy and reliability of four-hour performance data recording and reporting is at risk due to a lack of system controls, highly manual processes, and limited and inconsistent data validation practices. We found good practices in monitoring, tracking, and correcting data errors at one of the three hospitals we visited.

FirstNet does not prevent the recording of incorrect data

While FirstNet provides flexibility and functionality for clinicians to record patient treatment information, it does not have robust system controls to prevent errors in data entry. For example:

- it is possible to enter a physical departure time that occurs before the patient arrives (presentation time)—which results in a negative length of stay

- a patient may have a departure status of ‘discharged home’, but the departure destination may be recorded as an inpatient (hospital) ward. This means that data has been entered incorrectly.

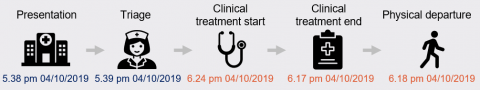

Case study 2 (Figure 3A) gives examples of negative times occurring in FirstNet data. These examples were reported by hospital and health services (HSSs).

|

Examples of negative times recorded in FirstNet |

|

ED presentations have five important timestamps: presentation, triage (assessing urgency of treatment), clinical treatment start, clinical treatment end, and physical departure. A negative time will occur if these times occur out of order. The following examples illustrate this. Hospital A: Clinical treatment starts after physical departure A patient’s clinical treatment cannot start after they physically depart the ED. This means that one or more times have been entered incorrectly.

Hospital B: Presentation time occurs after physical departure It is not possible for a patient to physically depart the ED prior to their presentation. In the above example, it appears that the incorrect date was recorded for the physical departure time, resulting in a negative length of stay. |

Queensland Audit Office from HHSs' data cleansing reports.

Manual data corrections have improved data quality—but at a cost

In the absence of robust system controls, staff must manually review FirstNet to ensure the data is accurate. Each of the three hospitals we visited had staff dedicated to validating and cleansing (correcting) ED performance data in FirstNet.

Incorrect data may lead to inaccurate performance reporting to the Commonwealth and the community, and may hinder the ability of HHSs to identify root causes for poor ED performance.

The Department of Health (the department) funded temporary data validation officer roles for hospitals using FirstNet from April to July 2019. This was in response to the increased workload involved in maintaining clinical and performance data integrity after these hospitals made the transition from EDIS (Emergency Department Information System—the previous system) to FirstNet.

Queensland Health has also developed a dashboard that highlights potential data validation issues for data teams to review. The aim was to reduce data errors and improve performance reporting. The department recommended that HHSs continue to fund dedicated data managers and data validation roles. However, not all HHSs have the financial resources to do so.

The data cleansing teams at the three hospitals we visited perform a labour-intensive daily data validation process. The scope of the data validation and cleansing activities is limited to:

- data with invalid time durations (such as negative or excessive times)

- instances where the four-hour performance target was not met.

This means data cleansing will generally lead to improved performance against the four-hour wait time target. The quality of the remaining FirstNet data is not being managed and may contain errors relating to patient demographics and treatment provided.

As a result, the performance reported to the Commonwealth and the community may not be accurate, funding for EDs may be at incorrect levels, and demographic data used for planning may not accurately reflect each hospital’s current needs.

Two of the three hospitals we visited reported that the extent of errors has decreased over time as ED staff became more familiar with FirstNet. For example, the Gold Coast University Hospital data team made amendments to 37.5 per cent of presentations in May 2019, but this had reduced to a still high 25 per cent in August 2019.

|

Better practice We observed good practices at Logan Hospital, where the data team monitored error types and provided weekly feedback to clinical and administrative staff. Its amendment rates decreased from 12.2 per cent in July 2019 to 1.3 per cent in September 2019. |

Audit logs of data changes are not monitored

Compared to the previous system EDs used, FirstNet has a better audit log function for tracking changes made to patient records, including timestamps for calculating emergency length of stay.

However, we found that none of the hospitals we visited had processes in place for reviewing changes made to FirstNet data. In the absence of proper monitoring, there is a risk of patient records, including treatment and departure timestamps, being altered and of these alterations not being detected.

An audit log is a chronological list of all entries and amendments to records. It provides documentary evidence of activities that have been changed or affected by a system operation, procedure, or event.

Submission of FirstNet data to the department occurs manually, which may lead to errors

The department collects ED data for performance reporting and funding purposes. The department has issued an Emergency Department Data Collection Manual, which outlines the appropriate process for managing and submitting data to ensure accuracy.

Hospitals using FirstNet need to manually extract data and submit it to the department monthly through a central portal. In comparison, hospitals using the older system do not need to submit data, as the department’s enterprise licence allows it to directly access that data.

The submission process for FirstNet data is manual and inefficient. It involves converting all clinical diagnosis codes to the different codes used by the older system, in order to maintain statewide consistency. Coding conversion involves manually copying and pasting data from Microsoft Excel files to text files. This increases the risk of undetected accidental data deletion.

As part of the submission process, hospitals can access system-generated validation reports, which identify invalid records, but only hospitals with dedicated data cleansing teams have the capacity to review validation reports.

Hospitals are unable to check if their submission is correct until after it has been received and uploaded by the department. The hospitals we visited reported instances when they needed to resubmit data multiple times until the department advised the data was complete and accurate.

Is the publicly reported performance of patient off stretcher time reliable?

The reliability of QAS’s publicly reported performance of patient off stretcher time (POST) is affected by a lack of system integration and real-time (instant) data validation checks.

In particular, completed records with invalid time intervals and incomplete forms are removed from reported data and are not being reviewed or corrected by QAS, the department, or the HHSs. This means that the number of patient transfers included in performance reporting is less than actual transfers. At some hospitals this can represent up to seven per cent of monthly transfers.

We are planning to undertake an audit on delivering ambulance services in 2022–23. The audit will examine how effectively and efficiently Queensland Health is addressing root cause issues impacting on ambulance performance.

Patient off stretcher time (POST) starts when an ambulance arrives with an emergency or urgent patient at the hospital. It ends when a patient has been physically transferred from the QAS’s stretcher to a treatment area in the emergency department and clinical handover to a clinician has been completed.

There is limited review of invalid time intervals

We analysed a sample of records for our three selected EDs and found that 4.63 per cent of completed forms had an invalid POST interval. The majority of the invalid intervals (3.17 per cent) were negative times.

QAS does not review invalid time intervals due to resource constraints. A review would involve investigating individual ambulance transfer records and identifying the correct time to be recorded. Because QAS does not undertake reviews, it is also unable to provide targeted training and advice to individual staff who frequently make data entry mistakes.

Invalid time intervals are primarily caused by data entry errors. For example, we observed multiple instances of the incorrect year being entered for handover time on the QAS’s iPads (used by paramedics to record detailed treatment and transportation information for each patient they attend), resulting in an invalid time interval.

The digital ambulance report form on the QAS’s iPads does not have validation controls to prevent incorrect dates or times being entered. In part, this is because the handover time is recorded in a different system from the ambulance dispatch system, which prevents real-time reporting and system validation.

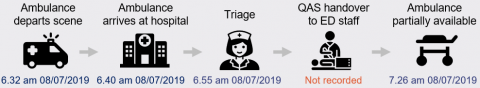

Case study 3 (Figure 3B) shows examples of invalid POST intervals.

|

Invalid POST intervals |

|

QAS records timestamps for the status of ambulances and patient transport. These are: depart scene, arrival at hospital, triage time, handover to ED staff, and partially available. Invalid POST intervals can occur when data is entered incorrectly. For example:

Handover time cannot occur prior to an ambulance arriving at a hospital. In the example above, it appears the handover time has incorrectly been entered as 4.20 am instead of 4.20 pm, which resulted in a POST interval of negative 11.9 hours.

While it is possible that a patient is not transferred off stretcher after eight hours, a POST interval above eight hours can also be the result of data entry errors. QAS assumes that a POST greater than eight hours is an error. In the example above, the handover time is more than 24 hours after the time the ambulance arrived at the hospital. The handover time is also after the time the ambulance was made partially available, which indicates the incorrect date was recorded for handover time.

Where a handover time is not recorded, a POST interval cannot be calculated, and the record is excluded from reporting as an invalid POST interval. In the example above, the ambulance arrived at the hospital and triage was completed; however, a handover time was not recorded. This means the POST interval for this patient is unknown. In February 2018, QAS made the handover time field mandatory when a patient has been ‘treated and transported by QAS’. |

Queensland Audit Office from QAS data.

User access reviews have been infrequent

QAS has a formal process in place to set up new user accounts for accessing the corporate network, dispatch systems, iPads, and databases. However, there has been limited or infrequent reviews of user access to ensure it is current and appropriate, and protecting patient confidentiality.

As a result, we found a number of employees who no longer worked for QAS but still had active user accounts. For example, corporate network accounts for 28 of the 71 employees who left QAS in April 2019 had not been deactivated by November 2019. We found seven of the 28 accounts were accessed after the staff separation date. QAS’s review found that the seven accounts did not access patient records after termination.

As a result of our finding, QAS initiated a number of user access quarterly reviews, including network access and critical systems. In October 2020, QAS’s ICT Management Committee approved the deactivation of 300 inactive user accounts. QAS now undertakes quarterly reviews of user accounts to ensure appropriate system access.

We reported similar risks in Report 10: 2018–19 Digitising public hospitals, where terminated staff could access integrated electronic medical record (ieMR) modules.

4. Implementing the 2014–15 recommendations

Have entities effectively implemented our recommendations?

The Department of Health (the department) and the hospital and health services (HHSs) have fully implemented two of the four recommendations we made in Emergency department performance reporting (Report 3: 2014–15).

Figure 4A summarises our assessment. (Our assessment criteria are defined in Appendix B.)

|

Recommendations made in Report 3: 2014–15 |

Status |

|---|---|

| It is recommended that the Department of Health and the hospital and health services: | |

|

1. ensure the definition of ‘did not wait’ is clearly understood by: 1.1. aligning the Emergency Department Information System (EDIS) terminology reference guide definition of ‘did not wait’ with the National Health Data Dictionary 1.2. clearly communicating and explaining to emergency department staff how the definition is to be applied 1.3. publicly reporting both the number and percentage of patients who did not wait for treatment and those who left after treatment commenced |

Recommendation fully implemented |

|

2. review the role of short stay units and formalise guidelines on their operation and management to reduce inappropriate inpatient admissions |

Recommendation partially implemented |

|

3. ensure data sets are accurate and verifiable by: 3.1. reviewing and implementing controls to ensure timely and accurate recording of patient information in EDIS 3.2. recording retrospective amendments that are evidenced and authorised 3.3. reassessing the constraints that led to audit logs being turned off, with a view to re-enabling audit logs and improving accountability |

Recommendation partially implemented |

|

4. prior to the completion of the National Health Reform Agreement—National Partnership Agreement on Improving Public Hospital Services, undertake a clinical, evidence-based review of the emergency access target to determine an achievable target or targets encouraging timely decision-making without compromising patient safety. |

Recommendation fully implemented |

Queensland Audit Office.

Recommendation 1—classifying patients who did not wait for treatment

Recommendation 1 was concerned with the correct classification of patients who left an emergency department (ED) without receiving treatment. These included those who did not wait for treatment and those who left after their treatment began.

- Did not wait for treatment—patients left before any treatment commenced.

- Left after treatment commenced—patients received some treatment but did not wait to be fully treated.

The difference between the two categories is important, as Queensland public hospitals receive Commonwealth funding for patients who leave after treatment commences but not for those who do not wait for treatment.

The department has fully implemented this recommendation.

In November 2014, the department aligned the definitions of ‘did not wait’ and ‘left after treatment commenced’ with those in the National Health Data Dictionary. It communicated the updated definition to hospital and health services (HHSs) through the emergency department terminology reference document published on the Queensland Health intranet. This addressed recommendations 1.1 and 1.2.

The Queensland Health hospital performance website now publicly reports on the number and percentage of ED patients who do not wait and those who leave after treatment commences. This addressed recommendation 1.3. Queensland Health suspended public reporting from February 2020 to September 2020 because of the national agreement to cease routine activities in order to increase capacity and manage the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Recommendation 2—using short stay units

|

Failure to fully implement this recommendation continues to result in inconsistent use, and a false level of assurance about ED performance. |

In our previous report, we found that formal guidelines were not in place for short stay units and as a result, these units may have been incorrectly used to meet the four-hour emergency access targets (the target time period for emergency department length of stay—ELOS). When a patient is admitted to a short stay unit, this stops the clock for the ED four-hour waiting time.

Short stay units are managed by, and form part of, emergency departments. They are designated treatment areas to manage acute problems for patients with an expected stay greater than four hours but less than 24 hours.

The department published guidelines in December 2014 that clarified the role of short stay units and has since updated them, but we found evidence of inconsistent practices. This means that the risk of inappropriate use remains. The guidelines specify that short stay units are not to be used:

- as a temporary ED overflow area

- to keep patients for the sole purpose of awaiting an inpatient bed, medical imaging, or treatment in the ED.

All three of the hospitals we visited for this follow-on audit had local procedures in place for short stay units. However, two of these were inconsistent with the department’s guidelines.

One local procedure allows for patients awaiting diagnostic procedures (such as computerised tomography (CT) scanning or ultrasound) to be admitted to the short stay unit. The procedure also allows stable patients to be physically moved to the short stay unit due to flow surge, in which case they are not to be recorded as a short stay unit admission in the system.

Another local guideline refers to short stay units accommodating patients for a stay of up to 48 hours. It also allows ‘anticipated discharge within 24 hours’ as a criterion for using short stay units.

All hospitals should ensure their local procedures are in line with statewide guidelines.

Recommendation 3—ensuring data is accurate and verifiable

|

Failure to fully implement this recommendation continues to expose Queensland Health to the risk of not detecting unauthorised data entries or changes. |

Recommendation 3 proposed additional controls in the system, including enabling an audit log function to ensure ED data is accurate and verifiable. Hospitals are not fully funded to implement controls and not all hospitals review data quality. This is discussed for hospitals that use FirstNet in Chapter 3. This means that recommendation 3.1 is not fully implemented.

When our previous report was published, all public hospitals used the Emergency Department Information System (EDIS) to record and report performance against emergency access targets. The department advised that re-enabling EDIS audit log functionality slowed the application to a non-usable speed. Hospitals have not implemented additional controls to evidence that changes are authorised and accurate; meaning recommendation 3.2 is not fully implemented.

Changes to emergency department systems since 2014–15

Since November 2015, 13 of the 26 reporting hospitals in Queensland have moved to FirstNet on a staggered approach. FirstNet is a module of the integrated electronic medical record (ieMR). (A list of these hospitals is available at Appendix F.) The remaining 13 hospitals are expected to move to FirstNet as part of future ieMR rollouts.

Recommendation 4—reviewing the emergency access target

Between 2011 and 2015, the Australian and state governments agreed on a national emergency access target that required hospitals to measure the proportion of patients admitted or discharged from emergency departments within four hours of arrival.

In our 2014–15 report, we recommended Queensland Health undertake a clinical, evidence‑based review of the emergency access target to determine an achievable target that would encourage timely decision-making without compromising patient safety. In 2014–15, no Australian state or territory was meeting the then four-hour target of 90 per cent.

Queensland Health fully implemented this recommendation.

In May 2016, Queensland Health clinicians led research into the effectiveness and impacts of four-hour targets. They studied acute ED presentations in 59 Australian hospitals over a four-year period. They found that reducing the four-hour target to 83 per cent of cases would not result in an increase in adverse clinical outcomes.

In 2016, as a result of this research, Queensland Health implemented a performance target of at least 80 per cent of patients having an emergency length of stay of four hours or less.